A Family Mystery, a Cancer Breakthrough, and a Sea of Uncertainty

In January 2022, when I was 32, I spit into a tube for genetic testing. Rather than mail the tube off to 23andMe or another ancestry service, I FedExed my saliva to Ambry Genetics, a company that assesses hereditary cancer risk by looking for mutations on genes that are associated with malignancies.I underwent testing 20 years after my mother died of lung cancer at 49 and 18 years after my father died of prostate cancer at 50, and after multiple medical providers recommended that I see a genetic counselor. They were concerned not just by my parents’ fates but by my extended family’s medical history, which is riddled with cancer. On my father’s side, one of my aunts had breast cancer before the age of 45 and was treated for skin cancer in her sixties; another had recently died of kidney cancer at 63. My grandmother died of colon cancer at 86. On my mother’s side, my grandfather died of lung cancer at 68, and my uncle died of myeloma at 64, decades after possible exposure to Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Given this history, I have always unconsciously assumed that I will one day get cancer. The genetic counselor wasn’t much concerned about my risk for lung cancer—unlike my mother and grandfather, I have never smoked—but my father’s metastatic prostate cancer and aunt’s early breast cancer meant that I met the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s genetic testing criteria for hereditary cancer. I agreed to have 30 of my genes assessed for mutations, including the well-known BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer genes—I was curious if genetics could explain my family’s tragedies. When my results came back negative for any known pathogenic mutations in the genes tested, part of me was relieved. As my genetic counselor explained, my results “greatly reduced the likelihood for several known hereditary cancer risk conditions.” But the overall picture of my family’s cancer history was still muddy. It was possible that my family was affected by mutations in one of the tested genes, but I had been spared. It was possible that scientists simply didn’t know yet about the genes and variants that could explain my family’s cancers. And my overall risk of one day getting cancer is still up in the air. Hereditary cancer syndromes are only estimated to explain about 5 to 10 percent of cancers. Most are caused by environmental and lifestyle factors (which likely explain those on my mother’s side), as well as aging (likely the culprit of my Grandma Martin’s cancer). Viruses like HPV are believed to cause another small portion of cancers, about 10 to 15 percent. What would it mean to me if I did one day find out that my genes foretold an increased risk for cancer? What might I do with that knowledge?Two years after my genetic testing, I still wonder whether researchers might someday find a mutation that explains the cancers in the Martin family. I felt this more strongly last summer, when another of my paternal aunts was diagnosed with cancer—this time, an early-stage colon cancer and an extremely rare cancer of the appendix—meaning that four of my grandparents’ five children had suffered from cancers, all different kinds. I’m cognizant of all we still don’t know about cancer, and I contemplate what better understanding might bring. What would it mean to me if I did one day find out that my genes foretold an increased risk for cancer? What might I do with that knowledge? These are conundrums that people increasingly face as genetic testing becomes widespread—even 23andMe can tell you if you might have some hereditary cancer gene variants, like BRCA1 and 2—and options for cancer prevention and surveillance remain imperfect and often extreme.Journalist Lawrence Ingrassia works through these tensions and others in his new book, A Fatal Inheritance: How a Family Misfortune Revealed a Deadly Medical Mystery. The book traces “both a heartbreaking story of family loss and an inspiring story of scientific achievement,” charting how over the course of decades, researchers painstakingly worked to prove that some cancers are hereditary and that genetic mutations explain why some families experience far more cancer than the rest of the population.For Ingrassia, this scientific quest was personal. His mother died of breast cancer at 42, in 1968. A little more than a decade later, his youngest sister, Angela, died of liposarcoma at 24. His other sister, Gina, died of lung cancer at 32. In between his sisters’ cancers, Ingrassia’s nephew, Charlie, then a toddler, was treated for a rare sarcoma in his cheek; he would later be treated for colon cancer in his early thirties, and die of metastatic bone cancer at 39. And Ingrassia’s brother, Paul—Charlie’s father—died at 69, just months after Charlie, of metastatic pancreatic cancer, his fourth malignancy after lung cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer. Father and son received chemotherapy at the same hospital at the same time, a detail that hit me in a sickening echo of my parents’ experien

In January 2022, when I was 32, I spit into a tube for genetic testing. Rather than mail the tube off to 23andMe or another ancestry service, I FedExed my saliva to Ambry Genetics, a company that assesses hereditary cancer risk by looking for mutations on genes that are associated with malignancies.

I

underwent testing 20 years after my mother died of lung cancer at 49 and 18 years

after my father died of prostate cancer at 50, and after multiple medical

providers recommended that I see a genetic counselor. They were concerned not

just by my parents’ fates but by my extended family’s medical history, which is

riddled with cancer. On my father’s side, one of my aunts had breast cancer

before the age of 45 and was treated for skin cancer in her sixties; another

had recently died of kidney cancer at 63. My grandmother died of colon cancer

at 86. On my mother’s side, my grandfather died of lung cancer at 68, and my

uncle died of myeloma at 64, decades after possible exposure to Agent Orange

during the Vietnam War. Given this history, I have always unconsciously assumed

that I will one day get cancer.

The genetic counselor wasn’t much concerned about my risk for lung cancer—unlike my mother and grandfather, I have never smoked—but my father’s metastatic prostate cancer and aunt’s early breast cancer meant that I met the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s genetic testing criteria for hereditary cancer. I agreed to have 30 of my genes assessed for mutations, including the well-known BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer genes—I was curious if genetics could explain my family’s tragedies.

When my results came back negative for any known pathogenic mutations in the genes tested, part of me was relieved. As my genetic counselor explained, my results “greatly reduced the likelihood for several known hereditary cancer risk conditions.” But the overall picture of my family’s cancer history was still muddy. It was possible that my family was affected by mutations in one of the tested genes, but I had been spared. It was possible that scientists simply didn’t know yet about the genes and variants that could explain my family’s cancers. And my overall risk of one day getting cancer is still up in the air. Hereditary cancer syndromes are only estimated to explain about 5 to 10 percent of cancers. Most are caused by environmental and lifestyle factors (which likely explain those on my mother’s side), as well as aging (likely the culprit of my Grandma Martin’s cancer). Viruses like HPV are believed to cause another small portion of cancers, about 10 to 15 percent.

Two years after my genetic testing, I still wonder whether researchers might someday find a mutation that explains the cancers in the Martin family. I felt this more strongly last summer, when another of my paternal aunts was diagnosed with cancer—this time, an early-stage colon cancer and an extremely rare cancer of the appendix—meaning that four of my grandparents’ five children had suffered from cancers, all different kinds. I’m cognizant of all we still don’t know about cancer, and I contemplate what better understanding might bring. What would it mean to me if I did one day find out that my genes foretold an increased risk for cancer? What might I do with that knowledge? These are conundrums that people increasingly face as genetic testing becomes widespread—even 23andMe can tell you if you might have some hereditary cancer gene variants, like BRCA1 and 2—and options for cancer prevention and surveillance remain imperfect and often extreme.

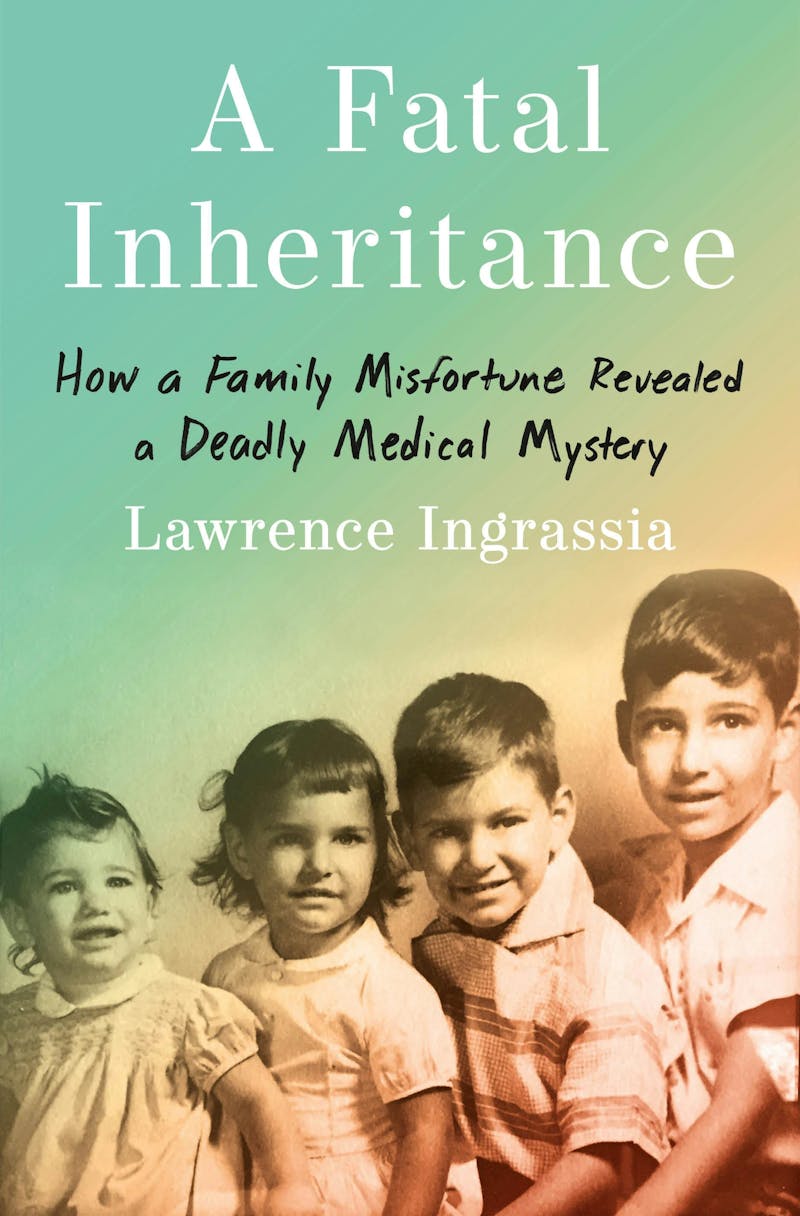

Journalist Lawrence Ingrassia works through these tensions and others in his new book, A Fatal Inheritance: How a Family Misfortune Revealed a Deadly Medical Mystery. The book traces “both a heartbreaking story of family loss and an inspiring story of scientific achievement,” charting how over the course of decades, researchers painstakingly worked to prove that some cancers are hereditary and that genetic mutations explain why some families experience far more cancer than the rest of the population.

For Ingrassia, this scientific quest was personal. His mother died of breast cancer at 42, in 1968. A little more than a decade later, his youngest sister, Angela, died of liposarcoma at 24. His other sister, Gina, died of lung cancer at 32. In between his sisters’ cancers, Ingrassia’s nephew, Charlie, then a toddler, was treated for a rare sarcoma in his cheek; he would later be treated for colon cancer in his early thirties, and die of metastatic bone cancer at 39. And Ingrassia’s brother, Paul—Charlie’s father—died at 69, just months after Charlie, of metastatic pancreatic cancer, his fourth malignancy after lung cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer. Father and son received chemotherapy at the same hospital at the same time, a detail that hit me in a sickening echo of my parents’ experience.

A year before cancer killed Ingrassia’s mother, Frederick Pei Li and Joseph Fraumeni, researchers in the epidemiology branch of the National Cancer Institute, or NCI, started following families like Ingrassia’s to determine the role heredity might play in cancer risk. It took more than 20 years, but eventually, scientists zeroed in on the mutated gene—TP53—that was responsible for the alarming rates of cancer in the families Li and Fraumeni had first studied. Like the BRCA genes, TP53 is a tumor-suppressing gene; when mutated, its cancer-eliminating powers are inactivated, allowing malignant cells to multiply out of control. Li-Fraumeni syndrome, or LFS, as the disorder came to be called, remains very rare—researchers currently estimate that there are only about 1,000 families worldwide with LFS—and devastating for those affected. People with LFS are predisposed to a wide variety of cancers, from breast to brain to lung to bone, and have a 90 percent lifetime risk of developing cancer. Fifty percent of those cancers will hit patients before age 30. As Ingrassia puts it, “One of the scariest things for families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome is that you never know when or where cancer will strike.” By contrast, women with the more common BRCA mutations have about a 50 to 60 percent chance of developing breast cancer, and the general population has only a 30 to 40 percent lifetime cancer risk—a risk that increases significantly with age.

Via genetic testing in 2015, Ingrassia belatedly learned that his family was affected by LFS. He did not inherit the TP53 mutation that predisposed so many of his family members to cancer. But even if Ingrassia’s family had known about LFS sooner, it’s not clear that doctors would have been able to do much to save the lives of his affected relatives. While researchers have celebrated each new development in the scientific community’s understanding of LFS, patients and their families continued to suffer.

At a 2010 Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Workshop at the National Institutes of Health, a man named Oliver Wyss made the tension clear. Wyss, whose children inherited his TP53 mutation, had already lost his son, Hudson, to a rare, aggressive brain cancer at age 3. When Wyss spoke at the workshop, his 8-year-old daughter, Abella, was being treated for her second cancer. She would die three years later. Ingrassia writes, “It had been forty-one years since the possibility of an inherited cancer syndrome was first raised, [Wyss] noted, but after years of research, the best that doctors could offer LFS families was intensive screening.” Wyss took the scientists to task, saying, “We have to find true cures to treat these genetic disorders.… Because I’m sure, if this will be your grandchild or your child, this would not be acceptable.”

A Fatal Inheritance thus forms testament to the power of scientific research, but also a stark reminder of how frustratingly incomplete our understanding of cancer remains, and of the very human costs of that incomplete knowledge. While reading Ingrassia’s book, it was hard for me not to lament for the patients whose lives might have been prolonged if scientific knowledge moved faster, if better cancer screenings had been available sooner, and if higher-quality treatment options materialized. In 2024, there are still no specific treatments for LFS patients.

Now in his early seventies, Ingrassia spent his career in newspapers, including reporting and editing stints at The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times; his journalistic chops are evident through not just the book’s extensive research—he recreates scenes from Li and Fraumeni’s early days at the NCI as though he had been in the room—but its brisk pace and clear exposition. Many chapters are less than five pages long, and Ingrassia renders complicated matters of molecular biology and genetics in digestible, everyday language.

A Fatal Inheritance is as much a history of cancer research as it is a personal reckoning with disease, and its heroes are scientists, whose backgrounds and exploits Ingrassia profiles in detail. New revelations in epidemiology and oncology drive the plot of the book forward, carrying the reader through six decades of investigation in just over 250 pages. Even with this condensed and appreciative look, Ingrassia doesn’t just focus on researchers’ wins—he dwells on their setbacks and failures too.

Throughout, I found myself frustrated by how much cancer research is beholden to the egos, whims, and presumptions of powerful people. Ingrassia highlights that through the 1970s, top researchers held fast to the theory that most cancers were caused by viruses—despite a lack of evidence to support this reasoning—and funneled funds toward identifying such viruses. For instance, shortly after President Richard Nixon heeded calls to declare a “war on cancer” in 1971, strengthening the NCI and improving research funding, he appointed a virologist to head the NCI, guaranteeing that millions of dollars would continue to flow to viral studies. Meanwhile, epidemiological research into hereditary causes of cancer, like the kind Li and Fraumeni began in 1969, was relegated to a “backwater” of the NCI.

Other researchers who focused on unraveling the mysteries of cancer running in families, like Henry T. Lynch, a physician geneticist at the University of Nebraska, were treated with skepticism by the rest of the field for decades. As Ingrassia notes, the establishment looked down upon Lynch’s 1964 study of families with staggering cancer rates in Nebraska, assuming that “if he were a first-rate scientist, he would have a position at a more prominent medical school or research institution.” That snobbery would prove shortsighted. In the 1980s, after advances in molecular biology and genomic sequencing, researchers were able to find a chromosomal defect that explained the hereditary colon cancer syndrome Lynch began theorizing in the 1960s; later, the genetic disorder would be named after him.

More broadly, discounting the idea that cancers could be hereditary had a painful cost for families like Ingrassia’s. Throughout A Fatal Inheritance, Ingrassia never loses sight of the ramifications of science’s slow progress. Juxtaposed throughout are the stories not just of Ingrassia’s own family’s cancers but those of other families who would eventually be diagnosed with LFS, most notably the extended Kilius family, one of the first clans Li and Fraumeni began studying in the late 1960s. A Kilius family tree at the front of the book underlines the stark reality of an inherited TP53 mutation. Across seven generations, twenty-three Kilius family members have died of cancer, the youngest at ages 2, 3, and 10, and the oldest at 66. The majority of the Kilius relatives with the TP53 mutation died in their twenties and thirties.

For the younger generations of the Kilius family with a known TP53 mutation and others with LFS, the best medicine has to offer is an intensive screening protocol, consisting of annual full-body and brain MRI scans, extensive bloodwork several times a year, and other forms of surveillance for children and adults—the goal being to identify potential tumors very early, when they are most treatable. Women may consider a prophylactic bilateral mastectomy, since LFS carries an 80 to 90 percent lifetime breast cancer risk.

While Ingrassia only lightly touches on the issue of finances, the high costs of medical care and insurance undoubtedly impact the screening and care people with LFS or suspected LFS might receive. Quality genetic testing is less cumbersome to access now than when it first dawned in the 1990s, but it is still exorbitantly expensive, and insurance providers may balk at covering it. My own insurer sent me a terrifying letter stating that my testing, for which Ambry billed thousands of dollars, was initially determined not to be “medically necessary”; thankfully, my doctors provided more persuasive information. This is to say nothing of the high costs of surveillance. And given the lack of tailored treatment options for LFS patients—and the anxiety that comes with undergoing continual cancer screenings—some people prefer not to even be tested for the mutation in the first place.

The Ingrassia family didn’t pursue testing for TP53 mutations until 2015—more than 20 years after it first became available—but their delay wasn’t willful. Instead, somewhat incredibly, their doctors did not raise the possibility that they might be afflicted with LFS before then. Ingrassia is evenhanded when he explains this, stating that LFS “was so rare that many oncologists treating patients hadn’t heard of it” even well into the 2000s, and arguing that “oncologists treating patients often don’t have time to read the latest scientific literature.” This struck me as too kind—especially since developments in hereditary cancer syndrome research were printed not just in scientific journals but, increasingly, in the pages of the very newspapers for which Ingrassia himself worked.

Testing would not have led to a cure for Ingrassia’s relatives, but it could have made a difference for Charlie, his nephew. Had his doctors known sooner that he had LFS, they could have pushed for an earlier colonoscopy to detect his colon cancer; an earlier diagnosis might have allowed them to use less radiation. As Ingrassia explains, radiation can spur cancer-causing mutations and is much riskier for patients like Charlie, whose “body had less natural ability to protect against radiation causing cells to begin growing out of control and becoming malignant.” His doctors suspect that the radiation he received to treat his colon cancer may have caused his fatal metastatic bone cancer.

Ingrassia remains optimistic that groundbreaking treatments for patients with LFS are on the horizon. Gene editing therapies like CRISPR might hold the key to correcting mutations in TP53 that affect patients with LFS, stopping their cancers at the source. But Ingrassia notes that such treatments may be decades away, and will come with their own costs, both financial and ethical.

In the meantime, general advances in cancer treatments, from immunotherapy drugs to more targeted chemotherapies, have made a difference in the survival rates of patients in general and LFS patients in particular. As Ingrassia points out, the average five-year survival rate after cancer diagnosis, a critical measure, was just 50 percent in 1977; it is now 67 percent. Still, “better five-year survival rates mean a lot less if you get cancer when you are under forty—as many LFS patients do,” he writes.

Some of the most affecting passages in A Fatal Inheritance come toward the end of the book, when Ingrassia shares posts from Facebook groups for LFS families of which he is a member. “To scroll through their posts is to visit an alternative universe, where the carefree, everyday world has been left behind and where fear constantly hovers,” he writes. He quotes a mother, who writes, “LFS is robbing me of my family. And no one understands what LFS is and can’t comprehend what you’re saying.… I’m dying on the inside.”

For Ingrassia, who lost his entire immediate family to LFS—save his father, who died young of a heart condition—understanding that an inherited mutation on one gene out of thousands was the cause underscored how random and uncontrollable our bodies’ fates are. In this, A Fatal Inheritance reminded me that as much as I wish to understand why my parents had to die so young, when my brother and I were so young—and however much I learn about this disease and its causes—that answer will forever be just beyond my reach.