Airfield assassin: Ukraine’s Palianytsia drone threatens Russian rear

Its precise features remain classified, but experts allow giving an educated guess about Ukraine's newest mysterious weapon

Since the start of its full-scale war against Ukraine in February 2022, Russia has been able to strike any part of Ukraine. Until recently, Ukraine could not reciprocate.

Reversing this asymmetry has been Ukraine’s top priority. Western partners have delivered critically important missile capabilities at incremental speeds but remain hesitant about deep strikes into Russia, leaving Kyiv to fight with one hand tied behind its back.

After two and a half years of war, the tide is changing. Ukraine’s long-range drone program is yielding results. Regular strikes on Russian oil refineries have disrupted the enemy’s fuel supply, while attacks on military airfields have damaged strategic bombers used to terrorize Ukrainian cities.

President Zelenskyy recently announced a significant advancement in Ukraine’s strike capabilities. The country has created a new long-range drone called Palianytsia and tested a ballistic missile. Zelenskyy stated that the first use of Palianytsia, “an absolutely new class of weapon,” against Russia occurred on Ukraine’s Independence Day, 24 August 2024.

According to sources from Ukrainian media outlet Ukrainska Pravda, this attack targeted an object in occupied Crimea.

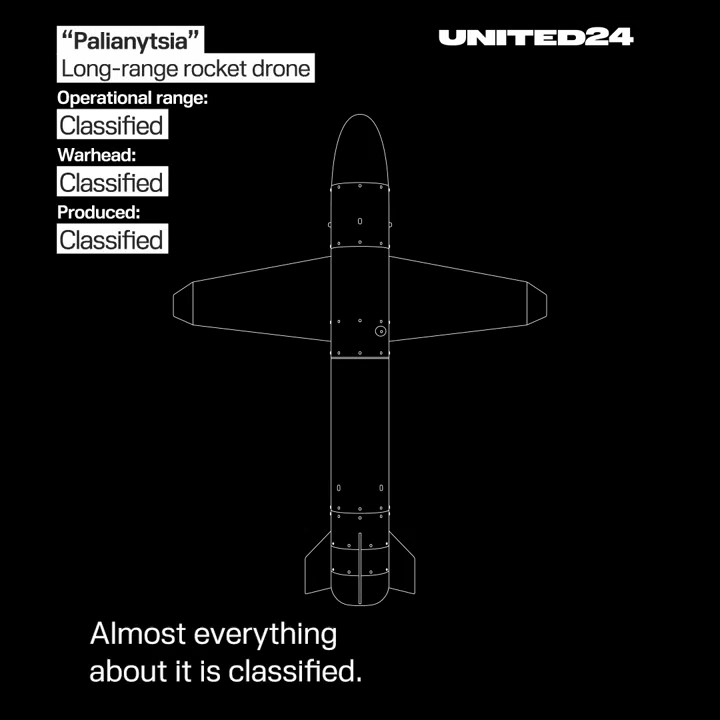

While the exact specifications of the drone remain classified, we delve into Palianytsia’s secrets with the help of experts.

Unveiling Palianytsia: Ukraine’s new long-range drone

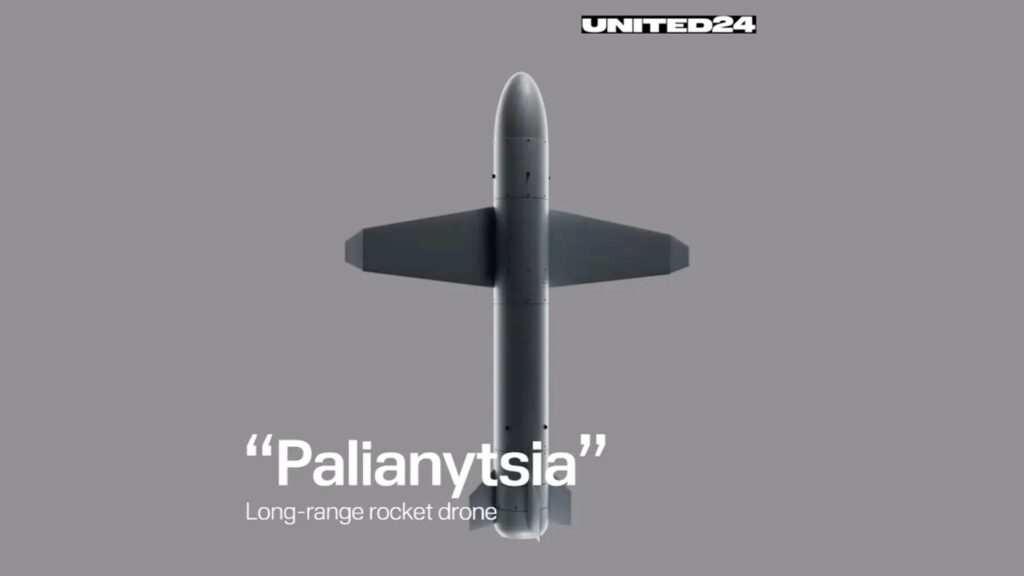

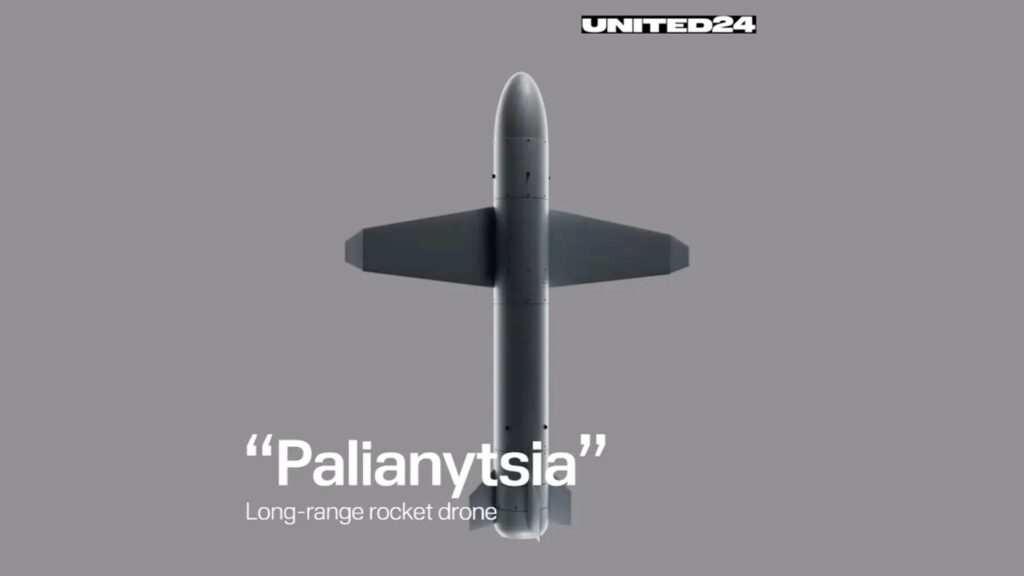

Two videos form the basis of our knowledge about Ukraine’s mysterious new weapon, named after a type of bread that Russians cannot pronounce properly, and is therefore used to unmask Russian spies.

- A video by state-owned United24 provides limited details, stating that the rocket drone was developed over 1.5 years. It launches from a ground platform, uses a turbojet engine, is equipped with electronic warfare countermeasures, and establishes its location via satellite.

The official designation “rocket drone” sparked debate among Ukrainian experts, who emphasized that it should be called a turbojet drone due to its jet engine, not a rocket engine.

Rocket engines typically use propellants to create thrust, expelling mass rearward to move the vehicle forward. This differs from jet engines, which use atmospheric air as part of their propulsion system.

- A video shared by Ukrainian military journalist Roman Bochkala on 24 August shows two men, likely volunteers, testing what he calls a “Ukrainian turbojet rocket drone.”

This winter footage reveals a weapon visibly different from the United24 version. While the “official Palianytsia” has wings at the front and four tail fins, this volunteer-tested rocket drone features small wings at the nose and larger detachable wings with downward-facing tips atop the fuselage. It also has a vertical tail stabilizer and launches from a wheeled robot chassis rather than a ground platform.

The turbojet engine remains the sole common element between these models.

Technical details and capabilities of Palianytsia

The model shown in the volunteer test flight is most likely an early version of Palianytsia that underwent further development, aviation expert Kostiantyn Kryvolap told Euromaidan Press. The final Palianytsia is most likely to have the same cylindrical form with large wings that can prolong the range of the low-thrust drone.

Some estimates of the UAV’s technical details can be gleaned based on the appearance of the UAV in the volunteers’ testing video.

The fuselage is approximately 2-2.5 meters long with a diameter of 40 cm. This is roughly half the size of the Ukrainian anti-ship missile Neptune, which famously sunk the Russian warship Moskva in 2022 – it is 5.5 meters long, with a diameter of 38 cm.

Therefore, its speed is roughly 500 km/h, it has a range of approximately 500 km, and can carry a warhead weighing between 60 and 100 kg, Kryvolap says. The payload and range are interconnected: the smaller the payload, the greater the range can be.

He noted that this payload capacity allows for flexibility in balancing range and destructive power.

The real Palianytsia’s range is likely larger: the United24 video’s thumbnail suggests a range of 600 km, while a map of strikes in the video shows airfields near Pskov and Savasleyka, which are 750 km from Ukraine’s borders.

Compared to cruise missiles, the proto-Palianytsia’s powerful wings create an aerodynamic surface that generates significant lift.

The shown aircraft approaches glider-like efficiency in terms of lift-to-drag ratio, a measure that estimates how long an aircraft can keep traveling horizontally for a given loss of altitude after engines are turned off.

A fighter jet, for instance, has a lift-to-drag ratio of 4.7, meaning it loses 1 km of altitude per 4.7 km of engine-less flight; passenger planes score 9-11, transport planes – 13-15, and gliders start from 20. The proto-Palianytsia’s glider-like build significantly enhances its range.

Further contributing to the drone’s extended range capabilities is the drone’s likely use of a fuel-efficient twin-circuit jet propulsion engine, Kryvolap notes. He estimated the thrust to be around 100 kilograms, give or take 20-30 kilograms — a relatively powerful engine for a drone of this size.

Thrust, the force that propels an aircraft forward, is a critical factor in determining its performance. Such thrust capacity could potentially allow the Palianytsia to achieve high speeds and long-range capabilities, especially when combined with its efficient aerodynamic design.

The large wings of the proto-Palianytsia are one of the turbojet drone’s main differences from a ground- or air-launched cruise missile, which have much smaller wings that unfold in flight and thus have a smaller lift-to-drag ratio. When the missile is launched from a jet or a ground launcher, tiny wings are the only option: for large wings to unfold reliably, they must have a sturdy connecting joint, which makes the entire construction much heavier.

The second difference is that the proto-Palianytsia is launched from a multi-use detachable chassis, not an airplane, special platform, or launcher. This reduces costs.

Ukrainian Digital Transformation Minister Mykhailo Fedorov has put an “under $1 mn” price tag on Palianytsia, but aviation expert Kostiantyn Kryvolap says this is a “surprising” figure. In aviation development, each 1 kg of thrust of a flying apparatus costs roughly $1,000, meaning Palianytsia’s estimated engine could cost $100,000. Guidance and control systems could cost an additional $20,000. Salaries and additional costs could take another $200,000, putting the ballpark figure of Palianytsia’s cost at $320,000, Kryvolap believes.

Trent Telenko, an American military expert and retired US Department of Defense civil servant, seconds this estimate: he believes that the price of the Ukrainian jet-powered drones can be in the $100,000-300,000 range.

Although Ukrainian officials said that Palianytsia is a new class of weapon, other turbojet drones exist. Notable examples include the Iranian Shahed-238 and British Banshee Jet 80.

Palianytsia’s strategic advantages: cheap, quick, more powerful

Ukraine’s movement towards developing a drone with a jet propulsion system has been long in the making, aviation expert and military technology founder Anatoliy Khrapchynskyi said in an interview with NV.

Electric motors are quiet and efficient but typically offer limited power and range and are used in smaller, shorter-range drones. Internal combustion engines are also used: they provide more power and longer ranges but are noisier and less stealthy.

Meanwhile, jet engines, or turbojet engines, offer significantly higher speeds and altitudes, allowing drones to penetrate enemy air defenses at high speeds and strike targets deep within enemy territory.

This advancement enables relatively small drones to operate at velocities and ranges previously associated with larger aircraft or missiles. Palianytsia’s higher speed is essential: Russians increasingly use small arms against Ukrainian drone attacks, so the faster the turbojet drone goes, the more effective it will be, Khrapchynskyi says.

It will also be able to evade helicopters that Russia uses against Ukrainian drones, defense expert Oleg Katkov believes: a helicopter with a maximum velocity of 300 km/h will be unable to shoot down a target moving at 500 km/h.

In developing Palianytsia, Ukraine is creating powerful weapons using cheap solutions, following in Israel’s footsteps, Khrapchynksyi added. After WWII, Israel received little help or modern technology transfers and was forced to invent weapons to defend itself.

It will allow Ukraine to continue pounding away at Russian airfields with increased efficiency.

Ukraine’s drone attacks have usually rarely led to Russian military aircraft destruction because the Russians manage to fly the aircraft out of danger before the slow drones moving at 150-180 km/h arrive. Nevertheless, Ukrainian drones still manage to destroy fuel and ammunition depots, as well as airfield infrastructure. Additionally, Russian aircraft are forced to move to more distant airfields, leading to fewer sorties and fewer gliding bomb launches.

Palianytsia, with its tentative speed of at least 500 km/h, is faster, has a larger payload, and may therefore allow for more destruction: Russia is unlikely to evacuate all the jets in the mere 20-30 minutes before the drone’s arrival. It is cheaper than a cruise missile, the price of which starts at $3 mn. It will be easier and quicker to launch into mass production.

“You win time, and time is of utmost importance for us. The faster we pound away at Russia, the faster we’ll get permission to pound away with foreign weapons,” Kostiantyn Kryvolap explains.

Trent Telenko especially stresses the cost-efficiency of Ukraine’s jet-powered drones. A mix of a “few dozen platinum bullets” (high-accuracy expensive cruise missiles) and hundreds of kamikaze drones “is how 21st-century wars are fought,” he wrote on X, stressing the cheaper drones’ role of not only striking targets but overwhelming enemy air defenses.

Nevertheless, a turbojet drone is more expensive than its slower counterparts with internal combustion engines. As well, it is unlikely to have guidance systems as sophisticated as Storm Shadow cruise missiles, Oleg Katkov believes.

In parallel, Ukraine continues developing a cruise missile version of its Neptune anti-ship missiles. Last year, Ukrainian officials announced that Neptune has a range of 670 km; this can be upped to 1,000 km, Kostiantyn Kryvolap told Euromaidan Press.

Ukrainian drones are increasing payloads, approaching FAB capacity

In general, Ukrainian developers are working to increase the payload capacity of their weapons from 60-70 kg to 100 kg, Kryvolap shares. If Ukrainian developers manage to raise this capacity to 150 kg, Ukraine will unlock the potential to use stockpiles of Soviet-era FAB bombs – the FAB-150, which has a payload of 50-60 kg.

The successful completion of this feat would be a creative military engineering solution that mirrors Russia’s gliding bomb strategy.

Since 2023, Russia has converted its vast reserves of dumb but potent FAB bombs into deadly precise gliding bombs by fitting them with glide kits: wings and a flight control module. When these DIY precision-guided munitions are detached from Su-34 fighter jets from an altitude of 10-12 km, they unfold their wings, lock onto a target with the help of GPS coordinates, and glide until deadly impact.

The upgraded FAB-250, weighing 250 kg, can glide 70 km until it hits its target. Heavier gliding bombs weighing 500-1000 kg (based on the FAB-500 and FAB-1000 respectively) have shorter ranges of 50-70 km.

Advanced versions of these bombs have seen engines installed on the upgraded FAB-250s, extending their range to 90 km.

Russia’s supplies of FAB bombs are basically limitless: they were produced at the end of WW2 in “quantities you can’t imagine” and now Russia has resumed their production at the Arsenal 53 factory, Kryvolap says. The explosives themselves may have gone obsolete but the metal shell can be filled with new ones, he adds – it is a “very primitive form of production,” Kostiantyn Kryvolap explains.

Ukraine has little means of countering these bombs, which have obliterated frontline territories.

Why didn’t Ukraine also convert its Soviet-era FAB reservoirs into deadly gliding bombs, like the Russians? It has much fewer jets that it can risk than the Russians – inadvertently, the fighter-bomber launching a glide bomb must approach the frontline and risk being picked up by an air defense system, Kryvolap says.

Not so with a drone. A UAV with a good guidance system could tap into Ukraine’s old FAB reserves without fear of losses to its precious military jet park and strike objects 700 km away, and Ukraine is rapidly approaching the creation of a drone with such lift power.

Palianytsia’s theoretical warhead of up to 100 kg already exceeds the 40-50 kg payload of the Iranian-designed Shahed-136 kamikaze drones Russia launches en masse at Ukraine. However, it is much smaller than the payload of cruise missiles. Storm Shadow, Taurus, and Kh-101 missiles carry 400-480 kg of explosives.

Hi! My name is Alya Shandra, I’m the author of this piece. I believe in the power of data and analysis, and that’s why we try to give you the best of it at Euromaidan Press.

Become our patron to help us bring you the best insights from Ukrainian and foreign analysts so we can cut through the noise together.

The future of Ukrainian drones

Palianytsia was most likely involved in a recent Ukrainian massive drone attack on Russia, when Russian authorities reported 158 drones downed above 15 regions, including capital Moscow.

This was likely the “final exam” of various types of Ukrainian long-range drones with different guidance systems before making decisions on their serial production, Kryvolap believes.

The aviation expert says many factors were involved for Ukraine to reach the stage of making such larger and more coordinated attacks.

- The drones needed to have detailed 3D elevation maps and be programmed to strike specific objects. In April 2023, when Ukrainian drone attacks on Russia were in their nascent stage, LeMonde reported that France turned down a Ukrainian request to provide such maps. But ever since, a crowdfunded satellite by Ukraine’s Prytula Foundation and footage captured by Ukrainian reconnaissance drones flying into Russia has enabled the creation of Ukraine’s own 3D elevation model that now enables drone strikes on Russia, Kostiantyn Kryvolap says.

- They have developed electronic warfare (EW) evasion techniques. Kryvolap explains that these drones are designed to be less susceptible to electronic warfare by minimizing signal emissions and reception.

- Advanced navigation systems are employed. Instead of relying on GPS, which can be jammed or spoofed, the drones use inertial navigation systems. Kryvolap describes this as a gyroscope system that operates independently of external signals.

- The guidance systems incorporate machine vision capabilities. This technology allows for improved target recognition and precision in strikes.

- These guidance systems are versatile and can be adapted to various platforms. Kryvolap notes that once developed, such systems can be implemented on different types of drones or missiles, adjusting for the specific characteristics of each platform.

- While the exact communication methods remain unclear, the drones likely have some form of secure communication with operators, though the specifics of how this works while maintaining stealth are not clear.

While Ukraine is in constant communication with NATO partners over military technologies and EW measures, Kostiantyn Kryvolap is unaware of any full transfer of guidance systems, meaning that the drones are likely employing domestic systems.

The development of such systems was enabled by the work of “very many different narrowly specialized teams and groups that gather, group, and fall apart” over more than a year, Kryvolap explains, stating that he was “in awe” of the participants of Ukrainian hackathons dedicated to military technology.

He underscores that Ukraine’s vibrant miltech private sector is the driver of the country’s progress and allows it to stay ahead of Russia.

Related:

- This is what can fix Ukraine’s Russian gliding bomb predicament

- Inside Ukraine’s secret FPV drone labs racing to stay ahead of Russia

- 500km game-changer: Ukraine’s ballistic missile breakthrough can alter war dynamics

- Ukraine now has drones rescuing fallen drones from hazardous battlefields