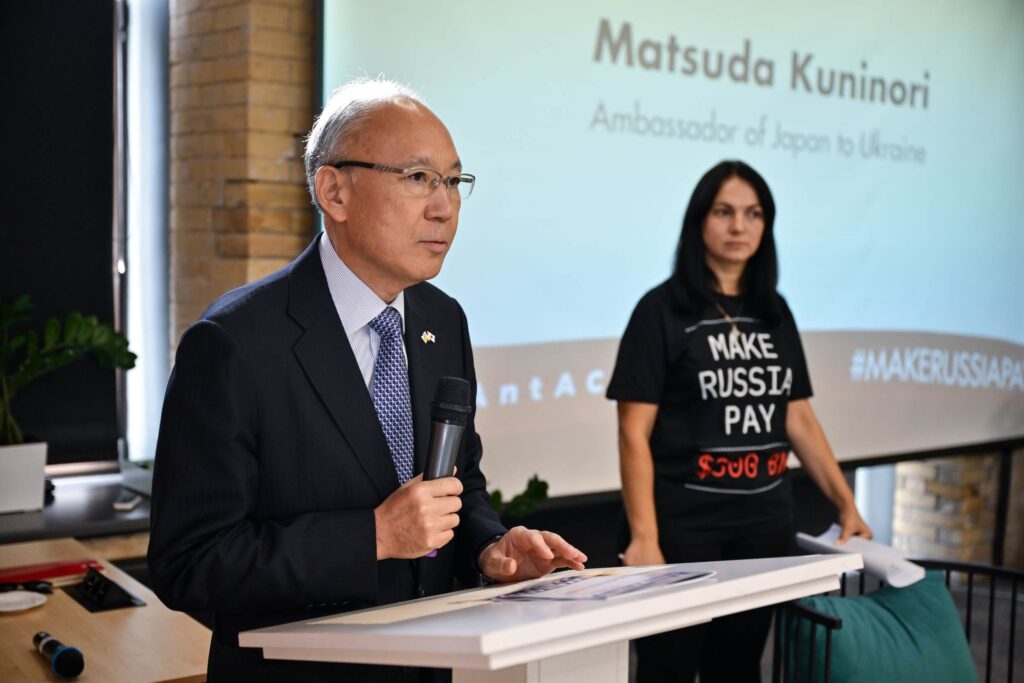

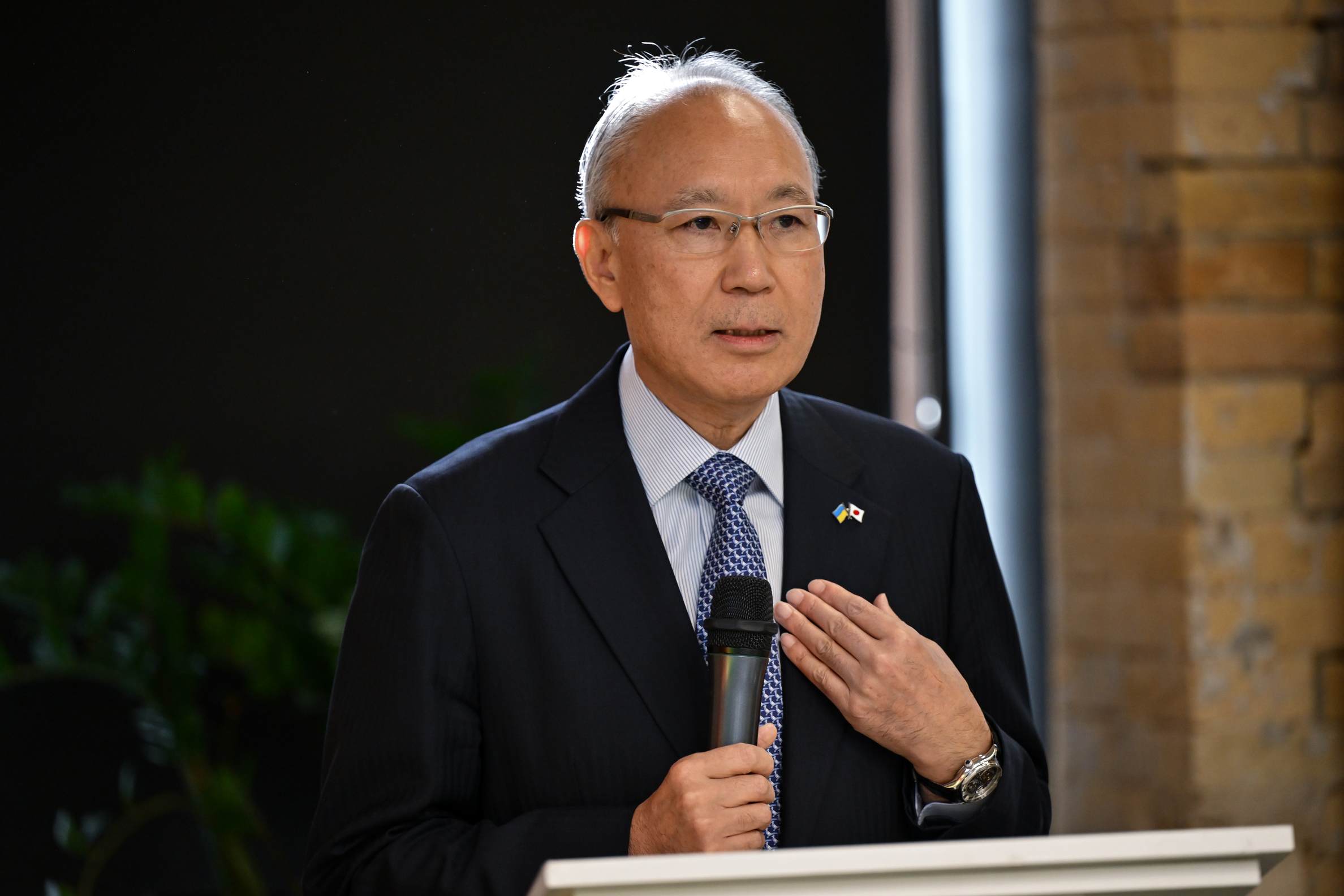

Ambassador: Japan’s support for Ukraine will remain steadfast, but non-lethal

In an exclusive interview, Matsuda Kuninori unveils Japan's dramatic policy shift on Russia, exposing a paradox at the heart of the nation's foreign policy: supporting allies in wartime without crossing the line into military assistance.

After Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Japan changed its Russia course drastically. The restrained reaction to Russia’s 2014 occupation of Crimea in hopes of reclaiming the Kuril Islands, with only mild sanctions being adopted under pressure from Western allies, was abandoned for a proactive approach. Japan joined the anti-Russia sanctions of other G7 countries, including asset freezes on over 1,000 individuals and entities, a ban on exports to military-related organizations, and the revocation of Russia’s “most-favored-nation” trade status.

Additionally, Japan provided substantial financial and humanitarian aid to Ukraine, pledging $12 billion in assistance, including $4.7 billion in grants aimed at bolstering Ukraine’s recovery efforts and funding for critical infrastructure projects, healthcare, and education.

However, military assistance is not on the horizon: Japan’s constitution renounces war and prohibits Japan from supplying weapons to “parties to the conflict,” which includes Ukraine as it fights off the Russian invasion.

As Prime Minister Kishida, under whose governance Japan made the radical change in its Ukraine policy, prepares to step down ahead of the 27 September 2024 elections, we talked to Japanese Ambassador to Ukraine Matsuda Kuninori and found whether Japan will continue supporting Ukraine, whether we can expect changes in terms of weapons exports, and why it abandoned its policy of rapprochement with Russia.

EP: Your Excellency, many Western countries are now acknowledging that their weak reaction to Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014 emboldened Russia and led to the full-scale invasion. Is Japan having regrets as well about not supporting Ukraine as much in 2014?

When we compare our actions in 2014 to what we are doing now, I think there is a lot of deep introspection for all countries. However, what we didn’t do back in 2014 gave us political and social strength in our response to Ukraine after the full-scale invasion. I hope we have learned the correct lessons from the past.

EP: Could you explain what caused the swing in Japan’s Russia-Ukraine policy? How did it come about and what is the discussion in Japan now?

The main theme of the discussion in Japan is that despite all the commitments Japan made to improve relations with Russia based on international law and order, it didn’t produce tangible results. On the contrary, Russia unilaterally started an invasion against Ukraine. This action is squarely against our own philosophy and the pillar of our foreign and domestic policy, which is based on law and order in the international community. That’s why my Prime Minister stated on day one of the full-scale invasion that there would be no more business as usual with Russia. We changed our policy to fully support Ukraine and extend the strongest sanctions against Russia, aiming to force Russia to immediately end this unnecessary aggression.

EP: Why does Japan not export weapons to Ukraine if its constitution renounces war?

This has been a subject of long discussions. We’ve come to the conclusion that each country in the international community, when it comes to helping Ukraine, should concentrate on what they can do better, quicker, or more effectively. This is the background against which we decided to provide Ukraine with robust budget support, humanitarian support, technical support, as well as non-lethal military support. We believe this is the best and fastest way for Japan to help Ukraine under the current political and legal conditions.

EP: But if we don’t win the war, there will be no need for economic support. We won’t have a country. Are discussions ongoing in Japan about whether this is the correct policy?

Different people have different ideas, but to be honest, when it comes to full-scale military support for countries outside Japan, there have been discussions constrained by the framework of our constitution and legal and political conditions. I fully understand that some people in Ukraine may feel frustrated. But believe me, we can divide responsibilities among international partners. Other countries can take care of full-scale military support, which is much better for them to be engaged in than Japan. Instead, Japan can focus more on other parts of support for Ukraine.

Additionally, Japan is actively restructuring its defense architecture to enhance military capabilities, with a goal of increasing defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027 and acquiring advanced weaponry to address regional security challenges posed by China and North Korea. This evolving military strategy emphasizes strengthening alliances with key partners, particularly the United States, and reflects both a need to support Ukraine as well as enhance Japan’s own defense posture amid rising tensions in East Asia.

EP: It appears to me that there are some similarities with Germany’s reaction. They also initially did not want to supply tanks to Ukraine, and it seems their policy of pacifism was similar to Japan’s because of your histories in World War II. Do you see any similarities, and do you see how this policy could be changing in Japan?

There is a clear difference between Germany and Japan. Germany is part of NATO and is physically located in Europe, while Japan is physically far away from Ukraine. Still, we feel the pain and we feel the threat that Ukrainians face. This is the background against which we are doing what we are doing.

EP: What can we expect from the new Prime Minister?

It depends on who is going to be the new Prime Minister. Believe me, it’s the first time in Japan’s history that nine candidates are running for the presidency of the governing party. To be honest, as of today, no one knows for sure. But one thing is crystal clear: whoever becomes the new Prime Minister and whatever new government is formed, our basic position of supporting Ukraine is not going to change.

EP: So it’s not controversial in Japanese society?

No, there’s no doubt about that.

- If Ishiba or Takaichi win, who are more aligned with aggressive defense strategies, Japan may see an increase in military aid to Ukraine.

- Conversely, if Koizumi were to take office, there might be a stronger emphasis on diplomatic solutions alongside military support.

EP: Finally, could you share how Japan is feeling amid this growing threat from Russia, North Korea, and China? What is your strategy for security in your region?

Every day we are more convinced about the direct connections between national security in Europe and the national security environment in East Asia where Japan is located. This means that we are now engaging with European affairs by supporting Ukraine. We definitely would like to increase our cooperation not only with the United States, our traditional ally, but also with NATO and European allies.

Related:

- Japan and Ukraine sign memorandum to fight corruption

- Kyodo: Japan to loan Ukraine $ 3.3 billion out of $ 50 billion from frozen Russian assets

- Zelenskyy honors Japanese PM Kishida, discusses energy support and sanctions