An Insider’s Portrait of Obama-Era Hope—and Disillusionment

The 2008 election of Barack Obama electrified a generation of Americans, who projected onto him almost limitless meanings. It also spawned a cottage industry of public thinkers whose affiliation with the Obama administration helped launch their careers: the Pod Save America hosts, former foreign policy speechwriter Ben Rhodes, adviser turned political consultant David Plouffe.New Yorker theater and TV critic Vinson Cunningham is no Obamanaut but, in a roundabout way, owes his career as a writer partially to the Obama campaign. As a twentysomething fresh out of college, the quintessential young person energized by the future president, he found himself working for the campaign as a fundraiser, making phone calls and soliciting donations. The experience did not lead to a life in politics for Cunningham; rather, it helped him to discover his current vocation, criticism. Cunningham’s autobiographical debut novel, Great Expectations, plumbs his year of aesthetic and political discovery on the campaign trail through his protagonist David Hammond’s time working for “the Senator.”There’s no shortage of novels that capture the general feeling and literary sensibilities of the Obama years—the optimism, the belief, then loss of faith, in meritocracy; the valorization of authenticity: Christian Lorentzen presented a taxonomy of “Obama Lit” on the eve of Trump’s inauguration. But few confront head-on the political call to arms felt by young left-liberals during those years. Equally rare is the critic just as able as a novelist as an essayist. With Great Expectations, Cunningham makes an impressive entry into both categories, capturing the feeling and the political substance, if only from the low rung of a field office, of those years, and turning the critic’s tools of analysis on his life and the life of his characters. I spoke with Cunningham about his critical and political development, the political frustration of early Obama supporters, and the roles of hope and religion in American politics today. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.Ben Metzner: You’ve spoken about the autobiographical aspects of the novel. Was there a moment that made you realize that there was a novel to be mined from your experience? Vinson Cunningham: The moment that made me think that I would write about this time and place and milieu was actually standing outside of Central Park, kind of with my back to the wall, because I’m looking up at an apartment building that I was about to go into. For whatever reason, that was the home of a rich person, or the kind of home that I would not have gone into before a certain sequence of events in my life. Just looking at the building with the renewed visual interest made me think that there was something to write about how events—sometimes parties, sometimes political moments, whatever—can change you irrevocably, change who you are and where you think you’re going. So I think that was the image that originated a lot of what ended up in the book.B.M.: Great Expectations draws on so many literary traditions: the campaign novel, the Künstlerroman, the novel of religious development, the recently dominant autofictional novel. I think this is important given that until now, you’ve been known primarily as a critic. What made this story feel like a novel for you, rather than an essay, for example, or a more straightforward political memoir?V.C.: If I’d written a political memoir, my actual experience on that campaign is not noteworthy or newsworthy in any way. One of my original impulses and drives as a writer was to write a novel. So it means simply that; I always wanted to write a novel. To me, I don’t know, if you’re going to write a novel and you care about other novels, the writing of a novel is itself a reading of other novels. So I was trying to not only write myself into traditions that I care about, but to sort of, in many cases, do a kind of, like, interpolation or, like, or even a parody of genres and modes and traditions that I care about. B.M.: The Obama campaign is often seen as a kind of last gasp of a politics of hope in the country. But David is already disillusioned by the end of the campaign; he says he’s “repelled” by politics. How much of David’s disillusionment is a young person’s first exposure to the world of politics, and how much is a reflection on politics in the twenty-first century?V.C.: It’s a reflection on lots of different things. Certainly it’s meant to reflect this current of disillusionment that you describe.9/11 happened when I was a senior in high school. While I was in college came Katrina, the Obama campaign, the financial crisis, Occupy Wall Street, on and on. This current, which does not just include the post-Obama period, is in fact, it seems to me, the direction of a quarter-century now. So certainly, some of that is there.But also, the novel is interested in hope not so much as political attitude but as a way of understanding fate. Hope becomes this

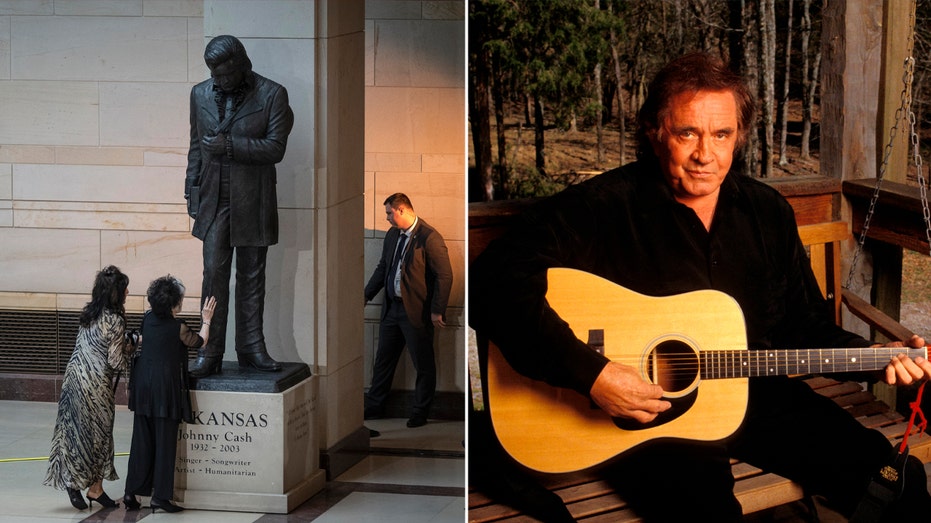

The 2008 election of Barack Obama electrified a generation of Americans, who projected onto him almost limitless meanings. It also spawned a cottage industry of public thinkers whose affiliation with the Obama administration helped launch their careers: the Pod Save America hosts, former foreign policy speechwriter Ben Rhodes, adviser turned political consultant David Plouffe.

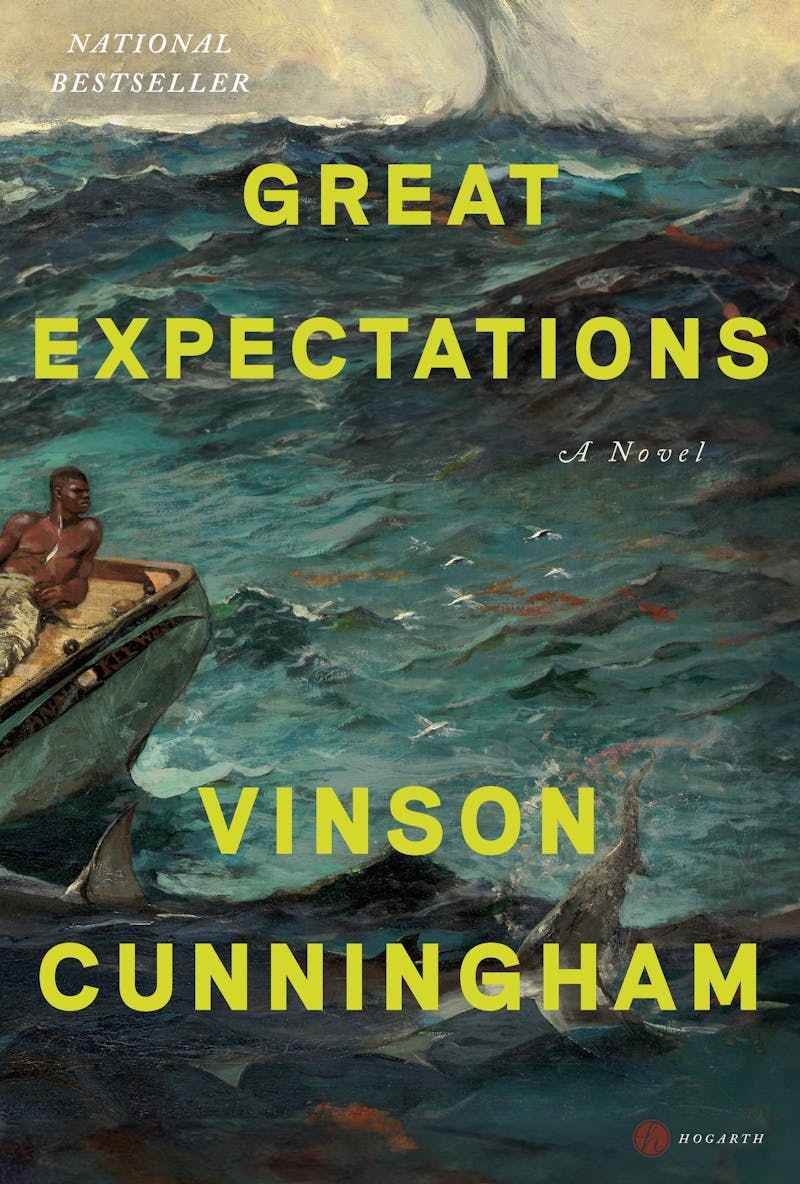

New Yorker theater and TV critic Vinson Cunningham is no Obamanaut but, in a roundabout way, owes his career as a writer partially to the Obama campaign. As a twentysomething fresh out of college, the quintessential young person energized by the future president, he found himself working for the campaign as a fundraiser, making phone calls and soliciting donations. The experience did not lead to a life in politics for Cunningham; rather, it helped him to discover his current vocation, criticism. Cunningham’s autobiographical debut novel, Great Expectations, plumbs his year of aesthetic and political discovery on the campaign trail through his protagonist David Hammond’s time working for “the Senator.”

There’s no shortage of novels that capture the general feeling and literary sensibilities of the Obama years—the optimism, the belief, then loss of faith, in meritocracy; the valorization of authenticity: Christian Lorentzen presented a taxonomy of “Obama Lit” on the eve of Trump’s inauguration. But few confront head-on the political call to arms felt by young left-liberals during those years. Equally rare is the critic just as able as a novelist as an essayist. With Great Expectations, Cunningham makes an impressive entry into both categories, capturing the feeling and the political substance, if only from the low rung of a field office, of those years, and turning the critic’s tools of analysis on his life and the life of his characters.

I spoke with Cunningham about his critical and political development, the political frustration of early Obama supporters, and the roles of hope and religion in American politics today. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Ben Metzner: You’ve spoken about the autobiographical aspects of the novel. Was there a moment that made you realize that there was a novel to be mined from your experience?

Vinson Cunningham: The moment that made me think that I would write about this time and place and milieu was actually standing outside of Central Park, kind of with my back to the wall, because I’m looking up at an apartment building that I was about to go into. For whatever reason, that was the home of a rich person, or the kind of home that I would not have gone into before a certain sequence of events in my life. Just looking at the building with the renewed visual interest made me think that there was something to write about how events—sometimes parties, sometimes political moments, whatever—can change you irrevocably, change who you are and where you think you’re going. So I think that was the image that originated a lot of what ended up in the book.

B.M.: Great Expectations draws on so many literary traditions: the campaign novel, the Künstlerroman, the novel of religious development, the recently dominant autofictional novel. I think this is important given that until now, you’ve been known primarily as a critic. What made this story feel like a novel for you, rather than an essay, for example, or a more straightforward political memoir?

V.C.: If I’d written a political memoir, my actual experience on that campaign is not noteworthy or newsworthy in any way. One of my original impulses and drives as a writer was to write a novel. So it means simply that; I always wanted to write a novel.

To me, I don’t know, if you’re going to write a novel and you care about other novels, the writing of a novel is itself a reading of other novels. So I was trying to not only write myself into traditions that I care about, but to sort of, in many cases, do a kind of, like, interpolation or, like, or even a parody of genres and modes and traditions that I care about.

B.M.: The Obama campaign is often seen as a kind of last gasp of a politics of hope in the country. But David is already disillusioned by the end of the campaign; he says he’s “repelled” by politics. How much of David’s disillusionment is a young person’s first exposure to the world of politics, and how much is a reflection on politics in the twenty-first century?

V.C.: It’s a reflection on lots of different things. Certainly it’s meant to reflect this current of disillusionment that you describe.

9/11 happened when I was a senior in high school. While I was in college came Katrina, the Obama campaign, the financial crisis, Occupy Wall Street, on and on. This current, which does not just include the post-Obama period, is in fact, it seems to me, the direction of a quarter-century now. So certainly, some of that is there.

But also, the novel is interested in hope not so much as political attitude but as a way of understanding fate. Hope becomes this weird tunnel between now and then; it’s like the vehicle on which one escapes the present and sort of gets a foretaste of a fate—not only personal but perhaps tribal, national, global.

And so on some level to be disillusioned with politics, to be repelled by politics, is really to say there are many possible domains, many possible hierarchies of thinking, that might lead one toward a fate. And one thing David says is, I’ve read this political language well enough that I understand it, and to understand it is almost the death of the kind of romantic view of the future. And he says, basically, that the hope that politics offers, he finds lacking in its connection, I think, to the kind of faith that he wants for himself, for his daughter, for his family, and for his future.

B.M.: The novel makes references to Jeremiah Wright and to the candidate’s own faith, and is concerned with David’s relationship to Christianity. Religion is obviously far from absent from American politics today, but, with a few exceptions, it no longer really seems to be a lexicon available for use to liberals. How does David make sense of this, and how do you?

V.C.: Yeah, I think that another way to read David’s disillusionment in the novel is to see him as having experienced the last gasp of a certain kind of political religion. We look at today’s Republican Party, yes, some of them use the language of various kinds of evangelicalism, various kinds of Christian nationalism. But if you poll Republican voters, you see how few of them, relative to a very recent past, go to church. So religious language has become more identitarian really, it’s more about a certain kind of identity than it is about any certain kind of metaphysics.

And you see that in the kinds of people that politics produces. For Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz to be the avatars of family values is hilarious. And one thing that Obama represented, at least for me, was the hope that the left side of the divide might step into the gap, and talk about care for the poor, care for the common home that is the Earth, in language that might borrow from the rhetoric of religion and strike a new chord. I mean, they failed at that in more ways than one can count. And so you see people outside of the strictly political taking over that mantle, like William Barber, the Poor People’s Campaign, others like that, sort of carrying that flame.

But religion has been so degraded and poorly used in politics that it just seems unfair, almost, to ask people of goodwill to respond to that kind of language. Fairly or not, religion and politics now seems like the precursor to some great scam or another. And to so badly abuse so great an inheritance seems to me sinful.

You know, I heard [Raphael Warnock] two summers ago give a sermon, preaching out of Isaiah, talking about, you know, making the rough places plain, this wonderful language of allusion and metaphor, about the God of justice, the God that makes wrong right, that brings mountains low and valleys high, you know, like, erases the disparities between peoples. That great language, it’s alien, you know, and it’s wasted on our political class. It’s really sad.

B.M.: This is also a novel about class—it’s not a coincidence that David’s job on the campaign is fundraising. He learns how to artfully solicit thousands of dollars from donors, but also how to navigate the moneyed worlds of cocktail parties on Central Park West and Oak Bluffs. You carefully sketch out David’s class position—he spends a summer ferrying between his home in Harlem and a relative’s apartment in a housing project in the Bronx. He has family that has suffered from homelessness, but he also attended a tony New York prep school. Why is this class education, and the kind of sociological excavation of race and class, so important to understanding David’s experience?

V.C.: I once wrote this piece about a program that I did as a kid called Prep for Prep. Helping kids from underprivileged, that’s what they used to call it, backgrounds, into private schools in middle school and high school. And so as a part of writing that piece I was trying to understand a process through which I had been, and also I think, a cohort of people, generationally, of which I’m a part. This is not just about Black working-class people or whatever, but this sort of moment of the highly mobile, highly sort of liquid meritocracy. Many of my friends are people who have benefited from that and whose class position is in this middle space. You know, one generation away from one thing and weirdly close to another thing. And so, one of my aims for the novel was to do a very classic fiction thing that we do in fiction, which is to pay close attention to class but to do it from this, I think, relatively new position. And so that was fun for me, this person who’s, class-wise, dislocated, and this is where again, criticism and the arts come in, because it seems to me that people who are not yet arrived or whatever, the mark of their mobility, people for whom education has been this engine, the arts becomes this hierarchy that is rapidly possible to ascend and therefore bridges the gap to other kinds of capital. So that kind of process was something that I wanted to see if I could depict.