Chasing Jane Austen’s Bad Boys

My first literary crush, as a preadolescent, was on Edward Fairfax Rochester, the sarcastic, beetle-browed hero of Jane Eyre, who formed my early beau ideal of what a romantic partner would be. Decades later, rereading Charlotte Bronte’s novel, I was taken aback to rediscover the scene where Rochester dresses up as a palm-reading “old crone” in a bonnet and cape and creepily interrogates Jane on her love life. Strange dude!Romantic archetypes in literature, argues English professor Rachel Feder in The Darcy Myth, penetrate our psyches in ways it’s important to interrogate: “The stories we’re brought up on are more than just stories. They become our personal mythologies.” For Feder, the romantic figure who resonates most powerfully in our culture is Fitzwilliam Darcy, hero of Jane Austen’s 1813 novel, Pride and Prejudice.The Darcy arc—for anyone who somehow missed not only the book but the gazillion adaptations (from Bridget Jones’s Diary to Pride and Prejudice With Zombies to even, apparently, Unleashing Mr Darcy, about competitors in a dog show)—is this: At the beginning of Pride and Prejudice, he’s a wealthy snob who refuses to dance with the heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, in a ballroom, and persuades his best friend to break up with Elizabeth’s beloved sister because her family are socially inferior. For the five Bennet sisters, marriage is a necessity. Due to Regency inheritance laws, they will instantly lose their home and livelihood to a male cousin on the death of their father. Yet when Darcy falls in love with Elizabeth “in spite of” his misgivings about her low status, she angrily rejects him. By the end, he’s been “properly humbled,” realizes Elizabeth is more than his equal, and they marry.Over the centuries as the book’s influence billowed out in ever-expanding waves, Feder argues, the narrative of the taciturn, arrogant man who transforms, magically, into a romantic hero under the special influence of a woman (who can see, as no one else can, his pain inside!) has grown potent and toxic. When she teaches Pride and Prejudice—which she loves—to her students, Feder says, she “ruins” it for them by forcing them to confront this dangerous aspect and how it’s lured them into unhealthy dating patterns. “It’s important,” she writes, “to reckon with how the Darcy blueprint has messed up our expectations of romantic prospects (especially men), from rude strangers at parties to emotionally withholding partners—all while generally twisting our ideas about love. (Real quick: it’s not your job to fix anybody, and rude people at parties are often just jerks.)”Though she says “especially men” here, Feder is careful to add that Darcys “proliferate across gender and other identity markers”: Anyone can be a Darcy or be hurt by one. Part relationship self-help book and part academic study, The Darcy Myth is full of these moments of girlboss wisdom; Feder surveys friends and colleagues to get real-life stories—from teenage girls to older gay men who tried and failed to effect the Darcy transformation—of miserable encounters with remote and unavailable partners. Her style is playful and smart, infused with Gen Z idiom (she’s “low-key obsessed” with the Crawford siblings in Mansfield Park; Lord Byron is a “fuccboi”) and the tropes of genre romance (after the agonies of a “will-they-won’t-they” plot, heroines get their “happy ever afters”). But the book’s strength emerges when Feder gives free rein to her scholarly voice, which ranges nimbly across genres and centuries—from raunchy eighteenth-century writer Eliza Haywood to Disney’s Beauty and the Beast movie, from Wuthering Heights’s saturnine Heathcliff (oddly, Rochester doesn’t get a look-in) to the Twilight series, from Mary Wollstonecraft to Taylor Swift—in search of Darcys old and new.She sees a clear link between Pride and Prejudice and early gothic literature, with its horror stories of abducted young women in gloomy castles, poisonings, and implied rapes, that was the bestselling genre of Austen’s youth (her first completed novel, Northanger Abbey, is an overt spoof of gothic conventions, though it hadn’t occurred to me to look for them in the rest of her works). To me, the idea of Longbourn (the home of the Bennets) as a haunted house—haunted by a death yet to come, that of Mr. Bennet—is powerful, because it’s hard, without this kind of framing, to fully convey the anxiety stalking the women in Pride and Prejudice, and by extension, Lizzie’s courage in disregarding it as she relies on her own moral compass. Feder uses the word “scary” a lot to describe the situation of women in Jane Austen—unable to earn income, at the mercy of rakes like Wickham and Willoughby (the bad boys of Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility, respectively), prone to unwelcome pregnancies (in Feder’s reading, Marianne Dashwood, heroine of the latter, suffers one of these, not just illness, when Willoughby abandons her, hence the need for an “apothecary” to administer an abortion).

My first literary crush, as a preadolescent, was on Edward Fairfax Rochester, the sarcastic, beetle-browed hero of Jane Eyre, who formed my early beau ideal of what a romantic partner would be. Decades later, rereading Charlotte Bronte’s novel, I was taken aback to rediscover the scene where Rochester dresses up as a palm-reading “old crone” in a bonnet and cape and creepily interrogates Jane on her love life. Strange dude!

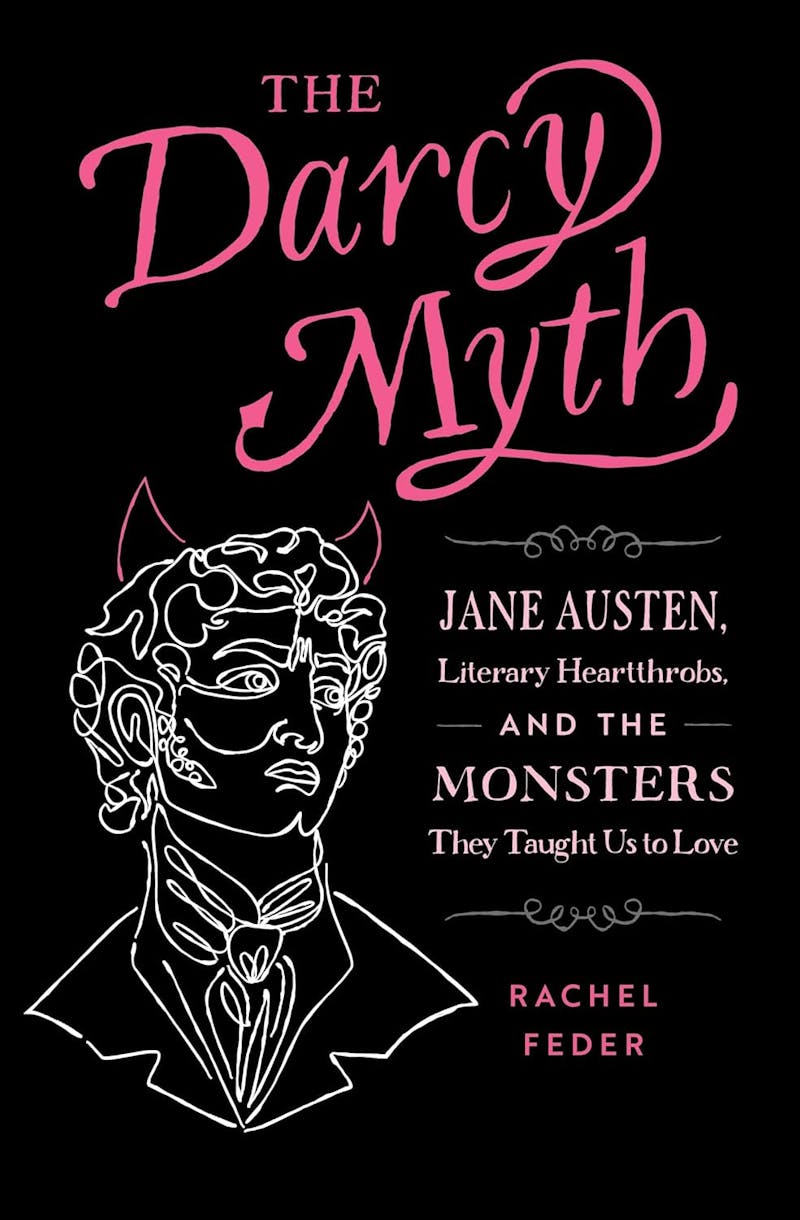

Romantic archetypes in literature, argues English professor Rachel Feder in The Darcy Myth, penetrate our psyches in ways it’s important to interrogate: “The stories we’re brought up on are more than just stories. They become our personal mythologies.” For Feder, the romantic figure who resonates most powerfully in our culture is Fitzwilliam Darcy, hero of Jane Austen’s 1813 novel, Pride and Prejudice.

The Darcy arc—for anyone who somehow missed not only the book but the gazillion adaptations (from Bridget Jones’s Diary to Pride and Prejudice With Zombies to even, apparently, Unleashing Mr Darcy, about competitors in a dog show)—is this: At the beginning of Pride and Prejudice, he’s a wealthy snob who refuses to dance with the heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, in a ballroom, and persuades his best friend to break up with Elizabeth’s beloved sister because her family are socially inferior. For the five Bennet sisters, marriage is a necessity. Due to Regency inheritance laws, they will instantly lose their home and livelihood to a male cousin on the death of their father. Yet when Darcy falls in love with Elizabeth “in spite of” his misgivings about her low status, she angrily rejects him. By the end, he’s been “properly humbled,” realizes Elizabeth is more than his equal, and they marry.

Over the centuries as the book’s influence billowed out in ever-expanding waves, Feder argues, the narrative of the taciturn, arrogant man who transforms, magically, into a romantic hero under the special influence of a woman (who can see, as no one else can, his pain inside!) has grown potent and toxic. When she teaches Pride and Prejudice—which she loves—to her students, Feder says, she “ruins” it for them by forcing them to confront this dangerous aspect and how it’s lured them into unhealthy dating patterns.

“It’s important,” she writes, “to reckon with how the Darcy blueprint has messed up our expectations of romantic prospects (especially men), from rude strangers at parties to emotionally withholding partners—all while generally twisting our ideas about love. (Real quick: it’s not your job to fix anybody, and rude people at parties are often just jerks.)”

Though she says “especially men” here, Feder is careful to add that Darcys “proliferate across gender and other identity markers”: Anyone can be a Darcy or be hurt by one.

Part relationship self-help book and part academic study, The Darcy Myth is full of these moments of girlboss wisdom; Feder surveys friends and colleagues to get real-life stories—from teenage girls to older gay men who tried and failed to effect the Darcy transformation—of miserable encounters with remote and unavailable partners. Her style is playful and smart, infused with Gen Z idiom (she’s “low-key obsessed” with the Crawford siblings in Mansfield Park; Lord Byron is a “fuccboi”) and the tropes of genre romance (after the agonies of a “will-they-won’t-they” plot, heroines get their “happy ever afters”).

But the book’s strength emerges when Feder gives free rein to her scholarly voice, which ranges nimbly across genres and centuries—from raunchy eighteenth-century writer Eliza Haywood to Disney’s Beauty and the Beast movie, from Wuthering Heights’s saturnine Heathcliff (oddly, Rochester doesn’t get a look-in) to the Twilight series, from Mary Wollstonecraft to Taylor Swift—in search of Darcys old and new.

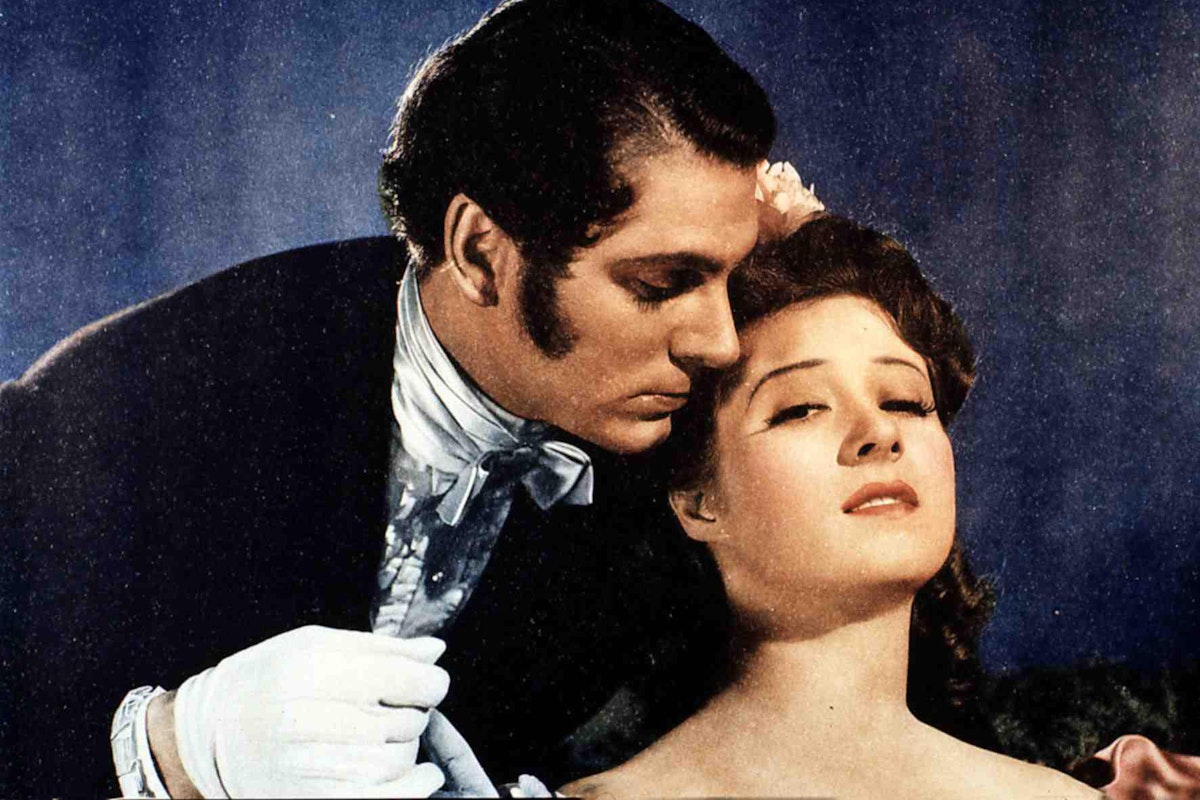

She sees a clear link between Pride and Prejudice and early gothic literature, with its horror stories of abducted young women in gloomy castles, poisonings, and implied rapes, that was the bestselling genre of Austen’s youth (her first completed novel, Northanger Abbey, is an overt spoof of gothic conventions, though it hadn’t occurred to me to look for them in the rest of her works). To me, the idea of Longbourn (the home of the Bennets) as a haunted house—haunted by a death yet to come, that of Mr. Bennet—is powerful, because it’s hard, without this kind of framing, to fully convey the anxiety stalking the women in Pride and Prejudice, and by extension, Lizzie’s courage in disregarding it as she relies on her own moral compass.

Feder uses the word “scary” a lot to describe the situation of women in Jane Austen—unable to earn income, at the mercy of rakes like Wickham and Willoughby (the bad boys of Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility, respectively), prone to unwelcome pregnancies (in Feder’s reading, Marianne Dashwood, heroine of the latter, suffers one of these, not just illness, when Willoughby abandons her, hence the need for an “apothecary” to administer an abortion). Yet she doesn’t dwell on the scariest part by far, which awaited women after their happy ever afters—childbirth, with its sky-high mortality rate. Jane Austen had four sisters-in-law who died in childbirth, and the specter of the dead mother—or the exhausted (Mrs. Price in Mansfield Park) or comatose mother (Lady Bertram, ditto)—certainly haunts her work.

In the section on Taylor Swift, Feder stops to linger on the song “All Too Well,” which she sees as a “textbook” Darcy myth. In it, Swift describes a short-lived love affair through a series of poetic flashbacks—dancing with her lover in the light of the fridge, getting lost upstate in a car—and the motif of a red scarf that she leaves with him. By visualizing these memories, Swift asserts her truth in the face of a partner (assumed to be Jake Gyllenhaal, who Swift dated when she was 20 and he was 29) who, it’s implied, is acting as though the relationship never happened.

The song’s massive popularity—and its ability to make grown men cry—testifies to the universality of the Darcy myth. Swift’s act of capturing the experience, turning it into art, both takes ownership of the myth and propagates it: “For what is an artist if not a kind of beast slayer, someone who, like Ann Radcliffe in her Gothic novels, looks at the fear young women experience and elevates it to art? The Gothic is as cozy as a red scarf symbolizing the virginity you gave to the bad boy who will never be the same.”

There were times, as the evidence of ghosting boyfriends and manipulative heartbreakers accumulated in this book, when my soul rose up in defense of the real Mr. Darcy. The Mr. Darcy of Jane Austen’s novel, after all, is not Jake Gyllenhaal. Though he has to shed his class assumptions to deserve Lizzie, he’s capable of unswerving constancy and genuine self-reflection. When Feder insists that his energetic act of redemption—tracking down the wicked Mr. Wickham, who’s eloped with Lizzie’s younger sister, Lydia, thus threatening the whole family with social ruin, and forcing him to marry her—is in fact an oppressive power play, that he’s “chaining Lydia to her predator,” she’s right to reclaim Lydia’s personhood but unfair to pin the whole Regency patriarchal structure on Darcy. For Lydia, sadly, marriage to Wickham is her best alternative—getting a college degree or reinventing herself as a TikTok influencer are not available options.

Similarly, though the Marianne-pregnancy theory is intriguing and fresh, it seems contradictory to Jane Austen’s intent, which is to show how a lover like Willoughby could almost kill a girl just through emotional carelessness. And by focusing the full weight of its attention on Pride and Prejudice’s hero, The Darcy Myth has the ironic effect of occluding the luminosity of the character really at its heart: Lizzie Bennet. In the end, the book is about her and her choices. Far from “fixing” Darcy, she intelligently assembles the clues that suggest he’ll be a worthy life partner.

Do we read novels for the instruction they provide for our own lives? Or as a reflection of life as it is: in Jane Austen’s case, for “the exquisite touch which renders ordinary common-place things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment,” as her hugely more successful contemporary Walter Scott wrote of her in his journal, 10 years after her death? (Scott himself, he admitted, could do “the Big Bow-Wow strain” as well as anyone, but Austen’s quieter gift was “denied to me.”)

Bruh, idk. But when we turn novels into “blueprints,” perhaps we risk stripping them of the quiet mysterious alchemy Scott recognized in Austen’s art. Feder openly acknowledges the mismatch between the Darcy myth and Darcy himself, though, and in the age of social media, it’s truer than ever that stories, once set in motion, gallop free in all directions. The Darcy Myth invites us to join Feder on an entertaining and thought-provoking ride along the way.