Cold War lessons show why West must abandon “escalation management” now

The Cuban Missile Crisis proved firm boundaries contained Soviet expansion - but today's cautious deterrence approach achieves the opposite effect, with political transitions in 2024 leaving a narrowing window to apply these historical lessons.

The West’s “escalation management” in Ukraine – limiting support to avoid provoking Russia – has achieved the opposite of its aims. While Western leaders debated each weapons system fearing escalation, Russia escalated anyway, secured new military partnerships, and learned that nuclear bluffing paralyzes Western decision-making.

Cold War history offers a clear lesson: the “escalation control” strategy – demonstrating strength and setting clear boundaries – contained Soviet expansion more effectively than showing caution. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, firm American positioning prevented escalation rather than invited it.

Now this lesson becomes urgent. Converging factors -– a new US administration, German electoral uncertainty, and Russia’s expanded military production -– may make strategic shifts nearly impossible.

Three immediate steps would correct this trajectory:

- Real security guarantees through an invitation to NATO

- Fast-track delivery of already-promised systems without new conditions

- Make clear, public commitments about the consequences for further Russian escalation

The choice is stark: return to proven containment strategies now, or face a much more dangerous and expensive conflict later.

The evolution of fear

“Escalation management” aspires to become the succinct definition of US and allied foreign policy approaches in countering Russian aggression.

Historically, US international behavior has oscillated between two extremes – isolationism and internationalism. Ukraine found itself in an unfortunate position, as Washington’s foreign policy pendulum swung toward global disengagement precisely when Ukraine needed decisive and substantial assistance most.

US de-escalation rhetoric, aimed at persuading global adversaries to resolve conflicts diplomatically, achieved the opposite effect – unifying the anti-American axis of Russia, North Korea, Iran, and China.

US de-escalation rhetoric united the anti-American axis of Russia, North Korea, Iran, and China

During the Cold War, US strategic vocabulary centered more on “escalation control” – largely opposite to the “escalation management” that the US has prioritized in recent years.

The US defined “escalation control” as the ability to dictate crisis progression, forcing adversaries into positions where they had to contemplate their responses.

The most notable example is the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when the Kennedy administration threatened a “full retaliatory response” to Soviet aggressive actions. Another telling example is the Truman Doctrine, which formulated the “containment” policy aimed at limiting the USSR’s and its satellites’ ability to spread communist ideas and establish pro-Moscow regimes worldwide.

This policy faced its first serious test during the Korean War (1950-1953), when the US engaged in an active military-political campaign against Kim Il-sung’s communist regime, supported by Moscow.

Compare key messages from Truman and Kennedy, who advocated proactive policies against Soviet expansionism. During the Cuban crisis, Kennedy emphasized:

“The 1930’s taught us a clear lesson: aggressive conduct, if allowed to go unchecked and unchallenged, ultimately leads to war.“ American President John F. Kennedy

In his 1956 memoirs, Truman reflected on the communist offensive against South Korea:

“If this were allowed to go unchallenged, it would mean a third world war, just as similar incidents had brought on the Second World War.“ US President Harry S. Truman

Ironically, both Truman and Kennedy were Democrats, like Biden, whose administration’s de-escalation strategy achieved greater escalation and discredited their foreign policy.

In the US, “escalation management” is considered successful based on two arguments:

- nuclear war was avoided and no Western country was attacked;

- and Ukraine hasn’t lost — Western support preserved Ukrainian statehood and thwarted Russia’s initial plans.

Biden implemented a policy of limited, cautious response, which US rivals exploited. Russian leadership, confident in their impunity, proceeded with the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The threat of escalation and potential Russian nuclear strikes became key in determining American aid to Ukraine. During discussions about weapons deliveries, Biden reportedly often asked: “Won’t this increase the risk of nuclear war?”. Russia, sensing these fears, regularly issued new nuclear threats.

Paradoxically, while the US and Germany lead in supporting Ukraine, they also lead in attempts to appease Putin by avoiding crucial decisions.

Paradoxically, while the US and Germany lead in supporting Ukraine, they also lead in attempts to appease Putin by avoiding crucial decisions.

The election period motivated US and German leadership to carefully consider public sentiment. While Biden aimed to prove he prevented World War III, Scholz exemplified caution – trying to help Ukraine without alienating German voters influenced by Russian narratives.

De-escalation leading to escalation

International media increasingly features voices from what our Center calls the “coalition of the resolute” — partners advocating for more decisive aid to Ukraine. These include influential politicians, advisors, experts, and journalists who often shape high-level decision-making.

Such articles are frequently confidential. The New Europe Center recently reviewed several key recommendation documents to Western governments regarding shifts in response to Russian aggression. Evidence suggests that some previously cautious political advisors, particularly in Biden’s circle, may be reconsidering their positions as they work to build a positive legacy in international security.

Russia interprets Western indecision as weakness and slow support as fear of Moscow.

Western governments showed signs of adjusting their support. The US administration strengthened its public rhetoric about Ukraine’s victory. In mid-September, reports emerged about US and British approval for long-range strikes against Russia. Intensive contacts between Washington, London, and Kyiv, alongside high-level Anglo-American discussions, provided grounds for optimism (the decision was ultimately made after US elections).

“Biden’s ‘escalation management’ in Ukraine makes the West less safe,” “How to win in Ukraine: pour it on, and don’t worry about escalation,” “Russia is probing NATO with attack drones and missiles. Ignoring them is a dangerous option” — these recent Western media analyses criticize failed Western approaches.

The key argument: the more the West tries to de-escalate with Russia, the greater the escalation becomes. Russia interprets Western indecision as weakness and slow support as fear of Moscow.

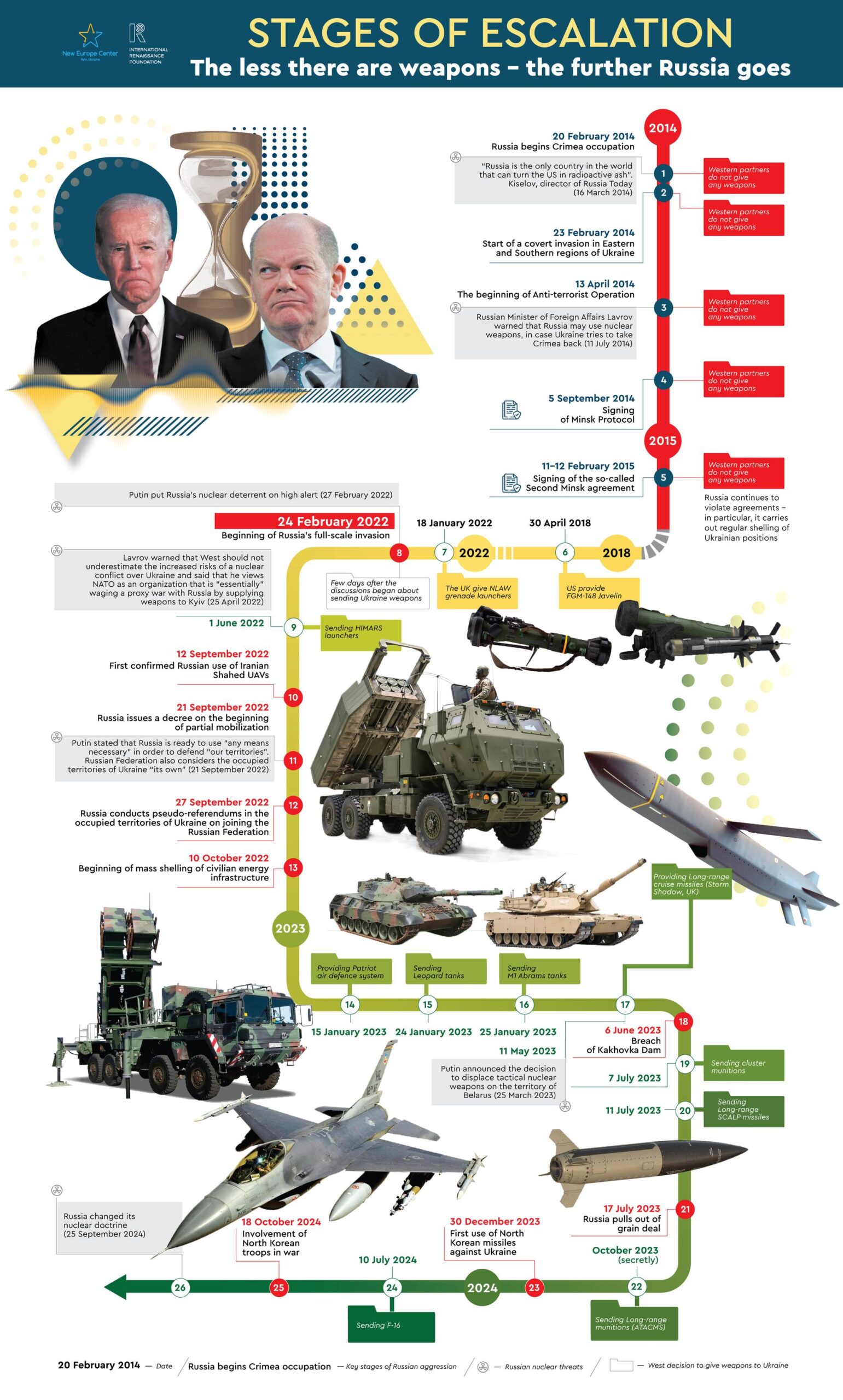

The New Europe Center developed a timeline showing how Russian aggression evolved — key escalations occurred precisely when the West hesitated. When Russia could have been stopped early on, Ukraine’s partners either provided no weapons or delivered them slowly, insufficiently, and of inappropriate types.

Moscow’s nuclear threats consistently accompanied its aggression:

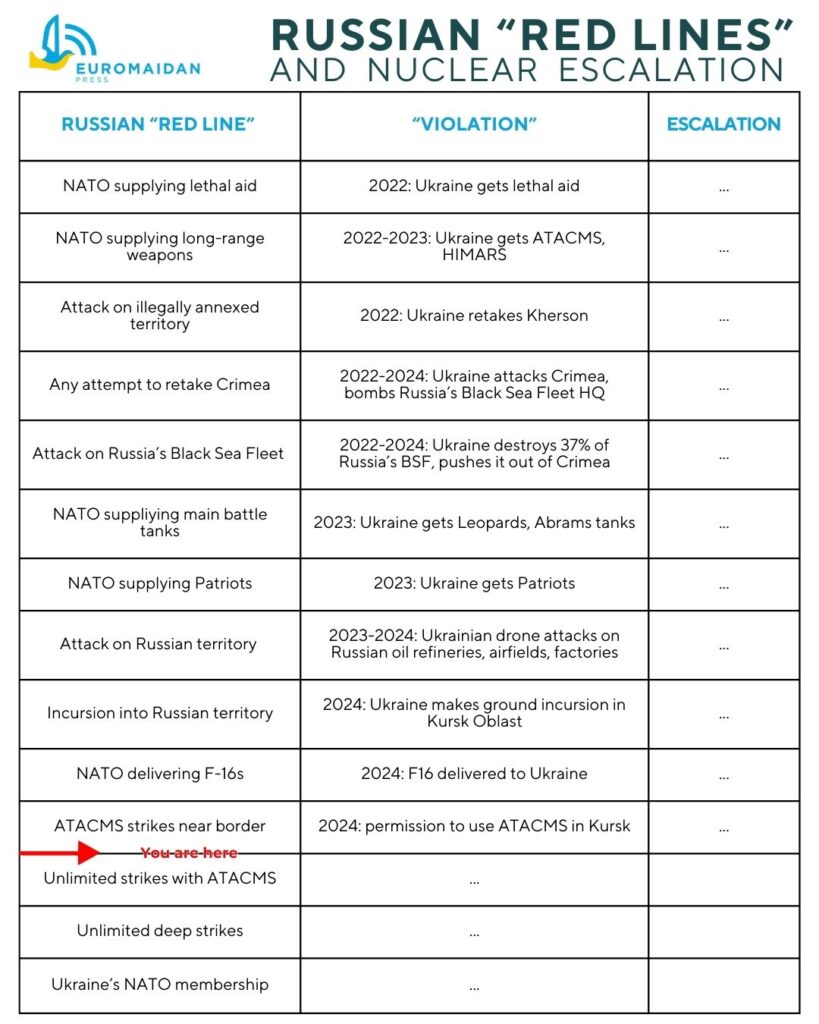

Russia has overused nuclear blackmail so frequently that the West should have grown immune. Yet, “nuclear” fears still influence Ukraine’s support.

US policy observers note that even with a 1% risk of Russian escalation, the US will not cross imaginary red lines.

Russia’s “escalate to de-escalate” strategy proved more effective than Western de-escalation approaches. Western slowness allowed Russia to adapt, build strength, and secure support from other dictatorships.

While the West should have learned fundamental lessons from failed de-escalation policies, Russia learned most effectively – expanding weapons production and building a loyal circle of allies who support Moscow without fear of escalation.

Western slowness allowed Russia to adapt, build strength, and secure support from other dictatorships.

Crucially, Russia realized it possessed the most effective weapon – bluff, requiring no resources yet working flawlessly: no need to strike with missiles, just promise to strike.

Western policy wasn’t entirely static. The New Europe Center’s timeline shows that the US, Britain, Germany, and France eventually crossed “red lines” (regarding HIMARS, Patriots, Leopards, Abrams, F-16 fighters).

While it is evident that Western support to Ukraine did not cause any Russian escalation, one might argue that neither did it force Russia to peace.

However, the issue isn’t just about weapons transfers, but their timing and volume. Slow action with numerous restrictions, as we’ve seen, poorly serves hopes for peace. Weapon transfers often came with stipulations about defensive use only, exclusively on Ukrainian territory.

For example, Western partners consistently emphasize strengthening Ukrainian air defense but reluctantly discuss Ukraine’s right to military response on Russian territory. However, even the most effective air defense can’t fully protect Ukraine (additionally, the West regularly failed to deliver promised systems). This led to extraordinary Ukrainian casualties – the aggressor could attack at will without fear of retaliation. In this situation, the West must invest billions in air defense systems, while Russia manages with lower costs for missiles and drones. Defense often costs more than offense. Consequently, most Russians remain unaware their country is at war. Meanwhile, in Western countries, escalation fear dominates electoral discourse – war fatigue, experienced only through television, influences political sympathies and empowers pro-Russian politicians.

The chosen defensive strategy led to social exhaustion in Ukraine and partner countries, but not in the aggressor state.

The West’s “escalation management” strategy has led to social exhaustion in Ukraine and partner countries, but not in Russia.

The last chance

Recent global media criticism of Western indecision, though belated, signals a psychological shift. However, this shift means little as it confronts numerous obstacles between breakthrough analytical recommendations and political decisions increasingly guided by public emotion favoring aggressor appeasement. However compelling expert voices may be, they can’t effectively compete with populist political promises.

Should we give up?

If Ukraine had accepted all Western fear-based approaches to escalation, Russia might have fully occupied it by now. Ukraine’s preserved statehood and Russia’s significant losses result from more proactive, risk-taking behavior. Whether regarding serious weapons or EU accession talks, what once seemed fantastical became reality through persistent criticism and compelling Ukrainian diplomatic arguments.

Russia’s raised stakes (including North Korean military involvement), combat intensity, and Ukrainian diplomatic efforts indirectly suggest both sides are preparing for a turning point.

Though neither declares this publicly, all eyes turn to the United States. Biden has an opportunity to present bold decisions that potentially offset previous years’ excessive caution. Primarily, this means inviting Ukraine to NATO, requiring US diplomatic talent to convince several Alliance opponents.

If Ukraine had accepted all Western fear-based approaches to escalation, it might have been fully occupied by Russia now.

The West has one last chance to partially correct previous shortcomings. Future conditions will become less favorable for ambitious decisions both internationally and within partner countries.

Biden’s administration’s current course corrections may prove insufficient or too late. Trump signals implementing opposite policies regarding Ukraine and Russia. Leadership change in the US and German elections create uncertainty benefiting, Russia. Moscow understands transatlantic unity likely faces its final weeks, potentially weakening US-EU solidarity for Ukraine.

Ukraine has reason to consider this stage the most vulnerable. The field for maneuvering with key partner decision-makers has narrowed dramatically. Trump has publicly indicated different war-ending views than the current administration. Germany’s situation is worse – entering election battles followed by coalition negotiations. German aid speed was always weak in responding to Russian aggression.

New US administration decisions might be rushed without proper consultation, sometimes benefiting Russia. German decisions might freeze entirely.

Ukrainian leadership must act more creatively, precisely, yet persistently. Partner mistakes and slowness aren’t new challenges. New administration attempts at diplomatic resolution might echo Zelenskyy’s early presidency efforts to dialogue with Putin. Perhaps this helps Ukraine’s president relate to Trump, explaining his evolution from believing in words to understanding military power’s importance — a journey from unilateral concessions to recognizing only coercion can “pacify” Putin.

What Ukraine needs to do

- Coalition of the resolute. Engage countries supporting stronger Ukraine assistance across political, diplomatic, expert, and media fronts. Despite criticism of Ukraine’s “unrealistic” expectations, advocacy must intensify. Clear objectives: concrete security guarantees focusing on NATO invitation, air defense shield over part of Ukraine, lifting restrictions on foreign weapons use, and mechanism for foreign troop deployment. Details in New Europe Center’s “Security Matrix” and NATO invitation formats.

- New US Administration and old friends. Build active communication with the new administration before the January 20 inauguration. In the early months, attempts may be made to restore the Russian dialogue, risking reduced Ukraine aid. Kyiv should develop communication with Trump’s circle directly and through old allies (e.g., former UK PM Boris Johnson).

- European emphasis. US likely to reduce aid, shifting burden to European allies. Ukraine must strategize acknowledging resource limitations, focusing diplomatic efforts on advocating increased European support (EU, UK, Norway).

- Narrative shift. Reaching European politicians becomes harder as public opinion grows vulnerable to pro-Russian rhetoric. Without convincing average French or German citizens that Ukraine’s war affects their interests, pro-Russian politicians’ rise becomes inevitable. Ukraine’s previous default support demand may no longer work. Intensify communication with audiences favoring quick negotiations, reminding of nearly 200 talks and 20+ Russian-broken ceasefires before the invasion.

- New opportunities. Leverage new options like South Korea’s engagement. Seoul military advisors could spark the French idea of European military instructors in Ukraine. The window for South Korean weapons (3.4 million surplus 105mm shells), Hawk, Mistral, Igla air defense missiles, and potential tactical missiles (KTSSM-II, Hyunmoo-2, Hyunmoo-3).

- Partner investment in Ukrainian military industry. Accelerate negotiations for Western investment in domestic weapons production. European defense industry can assist Ukraine while profiting from Ukrainian manufacturing investment, enabling transition to more complex equipment production. Details in New Europe Center’s “Can Europe Support Ukraine Alone?“.

- Russian asset confiscation.Continue efforts to confiscate Russian assets for defense sector investment. With most defense projects limited by funding, Western states seek alternative financing. Russian asset confiscation remains the largest funding source, with a portion invested in joint defense production.

Related:

- Why Ukraine’s fight is key to defeating Russia-China-North Korea alliance

- The West’s fear of escalation is Russia’s greatest weapon

- Biden was “killing Ukraine softly.” Trump won’t wait