Dagestani Jews look to rebuild after extremist attacks in the restive region of southern Russia

Jews in the predominantly Muslim region of Dagestan in southern Russia say they are determined to regroup and rebuild following a deadly attack by Islamic militants on Christian and Jewish houses of worship in two cities last weekend.The attacks in the regional capital of Makhachkala and the city of Derbent on Sunday killed 21 people — most of them police officers — and injured at least 43 others in the restive region in the North Caucasus on the Caspian Sea. Chief Rabbi of Russia Berel Lazar said a 110-year-old Derbent synagogue, which was a center for Jewish life in the region, was destroyed in a fire during the attacks. Among those slain was the Rev. Nikolai Kotelnikov, a 66-year-old Russian Orthodox priest who was killed as the faithful gathered on Pentecost, also known as Trinity Sunday, at a church in Derbent, which is Russia’s southernmost city and one of its oldest. “The message we are getting from the Jewish community in Dagestan is that they are not going to hide behind high walls and be intimidated by extremists,” said Lazar, who is affiliated with the Chabad-Lubavitch organization that refurbished the synagogue 20 years ago. “They are going to practice their religion openly,” he said. “They are optimistic that the government will take steps to protect them. They believe they can rebuild and get stronger.”In July 2013, Ovadia Isakov, who leads the Derbent synagogue, was shot while walking home in what officials called an antisemitic attack. Lazar said Isakov, who made a full recovery, now splits his time between Moscow and Derbent, serving that community during holidays and special occasions. In another incident, mobs rioted at the airport in Makhachkala as a flight landed from Tel Aviv shortly after the start of the war between Israel and Hamas in October. More than 20 people were injured when hundreds of men, some carrying banners with antisemitic slogans, rushed onto the tarmac, chased passengers and threw stones at police. The Derbent synagogue itself was almost like a “second rabbi” with Isakov now living in Moscow, said Varvara Redmond, a Dublin-based doctoral student at the University of Warsaw who has visited Dagestan three times and studied the Juhuro, as the Jews of Dagestan are called.“The building essentially replaced the rabbi,” Redmond said. “Everything happens through the synagogue, right from the purchasing of kosher meat to funerals, weddings and circumcisions.”Dagestan, with a population of about 3 million, is ethnically diverse with more than 40 tribes with as many languages. All are small communities with durable traditions. Marriage still largely takes place within the tribe.The Juhuro, also known as “Mountain Jews,” came from the Caucasus Mountains and are proud of their identity, shunning the “Jewish diaspora” label, Redmond said.While many Jews worldwide wish to be buried in Israel, Dagestani Jews are “very connected to their land” and prefer it as their final resting place, regardless of where they die, she said.Valeriya Nakshun, whose family fled Dagestan to the United States during Russia’s wars in neighboring Chechnya in the 1990s, said her ancestors considered themselves semi-Indigenous to the region because they came from Persia and the Levant centuries ago. She still has relatives in Makhachkala and Derbent, including her maternal grandmother.“They are still in shock after the attack and are still processing it,” she said. “Even though the synagogue is burned, they are grateful they are safe.”Her father, Boris Nakshun, grew up in Dagestan when it was part of the Soviet Union, at a time when Jews, Muslims and Christians were not allowed to practice their faith openly. Rituals such as circumcisions and weddings had to be done in secret and the relationship between all communities was largely cordial, he said.While Dagestani Jews celebrate the same holidays as other Jews, the traditions and foods are different. For Passover, Nakshun’s family cooks a rice dish with dried fruit and a thick crust at the bottom of the pot, herb stew and egg drop soup. On Yom Kippur, they light a candle on two separate trays, representing the living and the dead. “It’s like remembering your ancestors, but also praying for the living,” Nakshun said.The language of Dagestani Jews is known as Juhuri, a branch of the Tat dialect of Persian spoken by the local Muslims, said Ronald Shabtaev, a linguist and doctoral student at Israel’s Bar-Ilan University. Juhuri is spoken only by Jews, and has several dialects, he said.“Juhuri has not isolated the Caucasus Jews from the rest of the Jewish world,” Shabtaev said. “On the contrary, it has helped preserve Jewish heritage and tradition and maintain Mountain Jewish ethnoreligious identity.”Juhuri, which has a rich vocabulary with Hebrew and Aramaic words, is an endangered language — spoken or understood by fewer than 2

Jews in the predominantly Muslim region of Dagestan in southern Russia say they are determined to regroup and rebuild following a deadly attack by Islamic militants on Christian and Jewish houses of worship in two cities last weekend.

The attacks in the regional capital of Makhachkala and the city of Derbent on Sunday killed 21 people — most of them police officers — and injured at least 43 others in the restive region in the North Caucasus on the Caspian Sea.

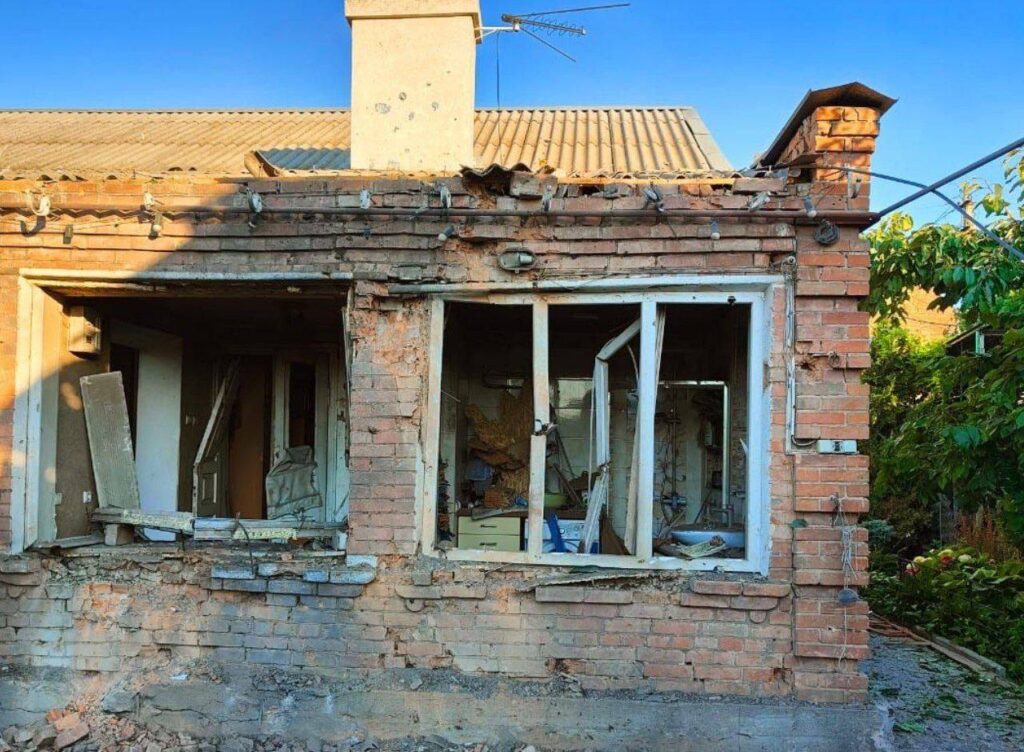

Chief Rabbi of Russia Berel Lazar said a 110-year-old Derbent synagogue, which was a center for Jewish life in the region, was destroyed in a fire during the attacks. Among those slain was the Rev. Nikolai Kotelnikov, a 66-year-old Russian Orthodox priest who was killed as the faithful gathered on Pentecost, also known as Trinity Sunday, at a church in Derbent, which is Russia’s southernmost city and one of its oldest.

“The message we are getting from the Jewish community in Dagestan is that they are not going to hide behind high walls and be intimidated by extremists,” said Lazar, who is affiliated with the Chabad-Lubavitch organization that refurbished the synagogue 20 years ago.

“They are going to practice their religion openly,” he said. “They are optimistic that the government will take steps to protect them. They believe they can rebuild and get stronger.”

In July 2013, Ovadia Isakov, who leads the Derbent synagogue, was shot while walking home in what officials called an antisemitic attack. Lazar said Isakov, who made a full recovery, now splits his time between Moscow and Derbent, serving that community during holidays and special occasions.

In another incident, mobs rioted at the airport in Makhachkala as a flight landed from Tel Aviv shortly after the start of the war between Israel and Hamas in October. More than 20 people were injured when hundreds of men, some carrying banners with antisemitic slogans, rushed onto the tarmac, chased passengers and threw stones at police.

The Derbent synagogue itself was almost like a “second rabbi” with Isakov now living in Moscow, said Varvara Redmond, a Dublin-based doctoral student at the University of Warsaw who has visited Dagestan three times and studied the Juhuro, as the Jews of Dagestan are called.

“The building essentially replaced the rabbi,” Redmond said. “Everything happens through the synagogue, right from the purchasing of kosher meat to funerals, weddings and circumcisions.”

Dagestan, with a population of about 3 million, is ethnically diverse with more than 40 tribes with as many languages. All are small communities with durable traditions. Marriage still largely takes place within the tribe.

The Juhuro, also known as “Mountain Jews,” came from the Caucasus Mountains and are proud of their identity, shunning the “Jewish diaspora” label, Redmond said.

While many Jews worldwide wish to be buried in Israel, Dagestani Jews are “very connected to their land” and prefer it as their final resting place, regardless of where they die, she said.

Valeriya Nakshun, whose family fled Dagestan to the United States during Russia’s wars in neighboring Chechnya in the 1990s, said her ancestors considered themselves semi-Indigenous to the region because they came from Persia and the Levant centuries ago.

She still has relatives in Makhachkala and Derbent, including her maternal grandmother.

“They are still in shock after the attack and are still processing it,” she said. “Even though the synagogue is burned, they are grateful they are safe.”

Her father, Boris Nakshun, grew up in Dagestan when it was part of the Soviet Union, at a time when Jews, Muslims and Christians were not allowed to practice their faith openly. Rituals such as circumcisions and weddings had to be done in secret and the relationship between all communities was largely cordial, he said.

While Dagestani Jews celebrate the same holidays as other Jews, the traditions and foods are different. For Passover, Nakshun’s family cooks a rice dish with dried fruit and a thick crust at the bottom of the pot, herb stew and egg drop soup. On Yom Kippur, they light a candle on two separate trays, representing the living and the dead.

“It’s like remembering your ancestors, but also praying for the living,” Nakshun said.

The language of Dagestani Jews is known as Juhuri, a branch of the Tat dialect of Persian spoken by the local Muslims, said Ronald Shabtaev, a linguist and doctoral student at Israel’s Bar-Ilan University. Juhuri is spoken only by Jews, and has several dialects, he said.

“Juhuri has not isolated the Caucasus Jews from the rest of the Jewish world,” Shabtaev said. “On the contrary, it has helped preserve Jewish heritage and tradition and maintain Mountain Jewish ethnoreligious identity.”

Juhuri, which has a rich vocabulary with Hebrew and Aramaic words, is an endangered language — spoken or understood by fewer than 200,000 people worldwide, including 30,000 in the United States, he said. Several Nakshun family members, including Valeriya Nakshun’s father and 96-year-old paternal grandmother, are among them.

The relationship between Jews and Muslims in Dagestan has been historically “layered,” but largely friendly, Redmond said. She saw people of different faiths greet their neighbors on the street and invite each other for tea.

“There is a high level of knowledge about each other’s religions, holidays and food habits,” she said.

But that has not ruled out tensions, including during the Chechen wars and the more recent increase in extremism, fueled in online spaces, Redmond said.

Rabbi Lazar said a majority of the Muslim population in Dagestan still has a good relationship with Jews and shares the dismay over Sunday’s attacks.

“This was not just an attack on Jews, but also on churches, the state and all people,” he said. “Most Muslims in Dagestan are also worried about this new wave of extremism. But we know that this is coming from outside the country and a very small percentage of Muslims are influenced by such ideology.”

He estimates that after an exodus of Jewish people during the Chechen wars, there are only about 500 families left in Derbent and about 200 in Makachkhala.

Lazar said he has not spoken with President Vladimir Putin after the attack, but is hopeful that Dagestan, including its Jewish community, will receive protection from the state.

Nakshun and her father are not too optimistic.

“I don’t think Putin cares about what happens in Dagestan or even understands what is happening there,” said Boris Nakshun, adding that the region is largely disregarded by Moscow, and that he continues to worry about family and community members who are left behind.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.