Danzy Senna’s Trick Mirror

No one has more fun with racial terminology than Danzy Senna. In her 2007 short story “Resemblance,” the N-word—as in the politically correct referent to the racial slur—drives a hilarious Who’s on First?–style gag. “Some white kids called their black substitute teacher an ‘N-word,’” a husband tells his wife. “They called the teacher a nigger? What’s the world coming to?” she responds. No, the husband clarifies. “They called him an N-word.” “I don’t understand,” she says. “Literally,” he explains. “They said, ‘Hey, N-word!’ Not ‘Hey, Nigger.’ ‘Hey, N-word!’”Delightfully absurd exchanges like this are a fixture of Senna’s droll and carefully observed fiction. She writes with a committed irreverence about biracial women and the social worlds and identities they straddle, and she dutifully avoids respectability or sentimentality. Even her most grounded stories seem to slant, the slipperiness of racial discourse and ideas tilting her characters’ lives toward the surreal. Crude and darkly comic constructions like “Jewlatto,” “Negrobilia,” and “one-dropper” abound in her work, each term reveling in the ways hybridity exacerbates the racialized desires and neuroses of American culture. A line from her twisty 2017 novel, New People, which skewers the romanticization of multiracial people, epitomizes her arch M.O.: “Every sentence is funnier with the word mulatto in it.” For Senna, identity politics is as much a playground as a battleground.Her latest novel, Colored Television, continues this subversive project. Building on her long-running interest in television as both a pastime and a trick mirror, the book is set in present-day Los Angeles, where novelist Jane Gibson wants to break into screenwriting. The career pivot is more a Hail Mary play than a creative shift. Jane and her husband, Lenny, a painter, are both wayward artists and untenured professors in desperate need of stability. They have two children, Finn and Ruby, but lack steady housing and employment. The family moves often, house-sitting for rich friends who “went away on sabbaticals and film shoots and retreats” and need “people to watch their possessions or pets or plants.” Jane’s family can access the outrageous wealth of the city, but they can’t claim it.Before Jane sets her sights on television, she’s keen on finishing the bulging book that she’s been writing for nine years—“her mulatto War and Peace,” as Lenny jokes. The push to complete it is both aspirational and obligatory. The family has spent six months in an opulent house owned by a friend who’s away in Australia, a period that has coincided with Jane’s academic sabbatical. The catch is that the friend and his family will return in five months, and her sabbatical will end around the same time, so she’s placing tremendous pressure on one book, but the reverie consumes her.The rare free time, and the splendor of the house, which has a courtyard, a stocked wine refrigerator, and five “special water-conserving toilets,” light a fire under Jane. If she could finish the book, she tells herself, “She’d publish it and get tenure, and they’d be middle class and maybe even have the money to buy a house of their very own.” She even has a neighborhood picked out, and has given it a nickname inspired by the idyll setting of The Andy Griffith Show: “Multicultural Mayberry.”Senna structures the plot around this swelling fantasy of upward mobility, which intensifies and begins to fracture as Jane completes her book. She goes to her office on campus and runs into a fellow professor who, having returned from sabbatical without a book, was punished with a horrible teaching schedule. The colleague, who appears to be unhoused, sleeps at the school, a sight so disturbing to Jane that she runs away. When Jane returns home and adds another character to her book, the act reads as a rejection of her colleague’s fate.After she finishes it days later and sends it to her agent, she starts to celebrate before she even hears back. She begins wearing the clothes of their hosts, as if she can attain wealth through osmosis. As she has “long and complicated” sex with Lenny, she imagines a past version of herself “outside in the garden, her face pressed against the glass, watching,” one of many doublings of her consciousness. And she throws Ruby a birthday party they can’t afford, hiring a magician and buying an expensive doll. She even takes the family to an open house in Multicultural Mayberry, despite the house “being way out of their price range, given that their price range was zero.”Her delirious optimism becomes a kind of double vision that overwrites the city’s landscape and history like a power-drunk architect:Gone was the suburban wasteland of Glendale and the trashy mini-mall sprawl of Mid-City. Gone was the relentless existential hum of the freeway, the racial blight of the LAPD, the handsome lying face of O.J. Simpson and the blank, bewildered face of his murdered wife, Nicole. Gone was the banally evil face of

No one has more fun with racial terminology than Danzy Senna. In her 2007 short story “Resemblance,” the N-word—as in the politically correct referent to the racial slur—drives a hilarious Who’s on First?–style gag. “Some white kids called their black substitute teacher an ‘N-word,’” a husband tells his wife. “They called the teacher a nigger? What’s the world coming to?” she responds. No, the husband clarifies. “They called him an N-word.” “I don’t understand,” she says. “Literally,” he explains. “They said, ‘Hey, N-word!’ Not ‘Hey, Nigger.’ ‘Hey, N-word!’”

Delightfully absurd exchanges like this are a fixture of Senna’s droll and carefully observed fiction. She writes with a committed irreverence about biracial women and the social worlds and identities they straddle, and she dutifully avoids respectability or sentimentality. Even her most grounded stories seem to slant, the slipperiness of racial discourse and ideas tilting her characters’ lives toward the surreal. Crude and darkly comic constructions like “Jewlatto,” “Negrobilia,” and “one-dropper” abound in her work, each term reveling in the ways hybridity exacerbates the racialized desires and neuroses of American culture. A line from her twisty 2017 novel, New People, which skewers the romanticization of multiracial people, epitomizes her arch M.O.: “Every sentence is funnier with the word mulatto in it.” For Senna, identity politics is as much a playground as a battleground.

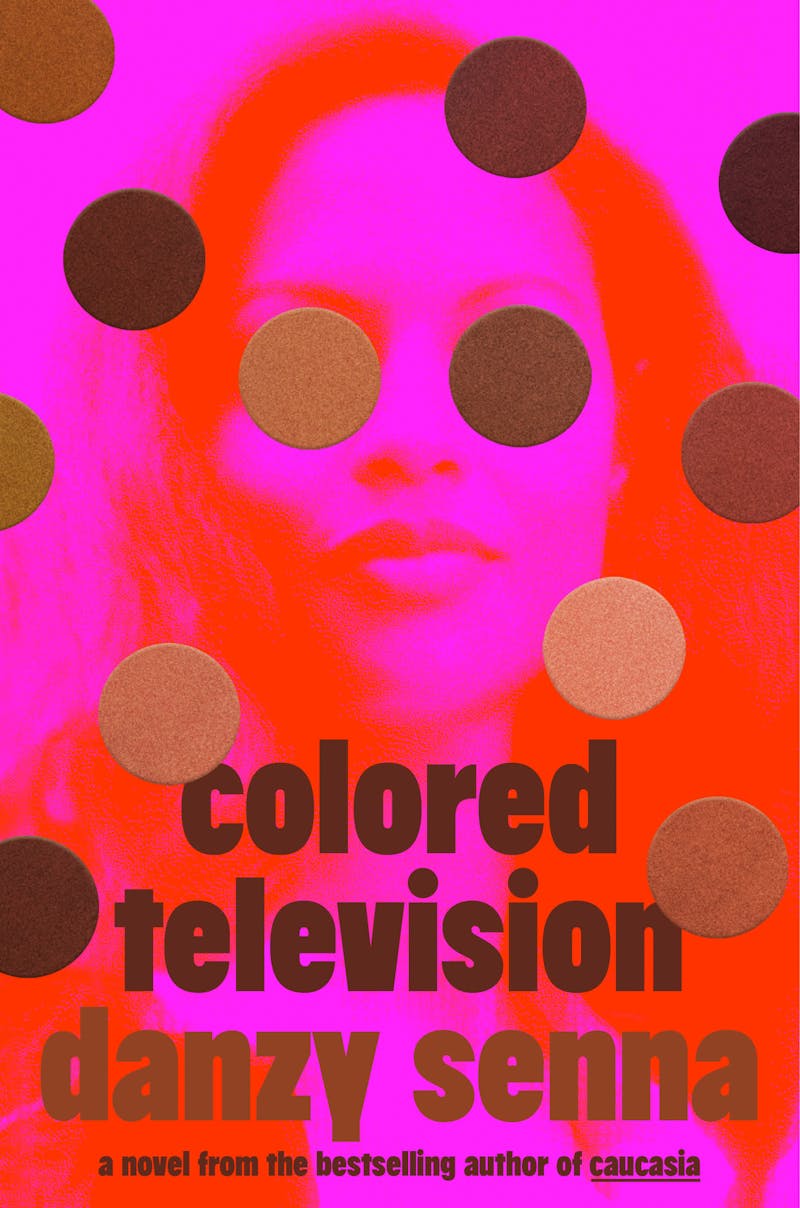

Her latest novel, Colored Television, continues this subversive project. Building on her long-running interest in television as both a pastime and a trick mirror, the book is set in present-day Los Angeles, where novelist Jane Gibson wants to break into screenwriting. The career pivot is more a Hail Mary play than a creative shift. Jane and her husband, Lenny, a painter, are both wayward artists and untenured professors in desperate need of stability. They have two children, Finn and Ruby, but lack steady housing and employment. The family moves often, house-sitting for rich friends who “went away on sabbaticals and film shoots and retreats” and need “people to watch their possessions or pets or plants.” Jane’s family can access the outrageous wealth of the city, but they can’t claim it.

Before Jane sets her sights on television, she’s keen on finishing the bulging book that she’s been writing for nine years—“her mulatto War and Peace,” as Lenny jokes. The push to complete it is both aspirational and obligatory. The family has spent six months in an opulent house owned by a friend who’s away in Australia, a period that has coincided with Jane’s academic sabbatical. The catch is that the friend and his family will return in five months, and her sabbatical will end around the same time, so she’s placing tremendous pressure on one book, but the reverie consumes her.

The rare free time, and the splendor of the house, which has a courtyard, a stocked wine refrigerator, and five “special water-conserving toilets,” light a fire under Jane. If she could finish the book, she tells herself, “She’d publish it and get tenure, and they’d be middle class and maybe even have the money to buy a house of their very own.” She even has a neighborhood picked out, and has given it a nickname inspired by the idyll setting of The Andy Griffith Show: “Multicultural Mayberry.”

Senna structures the plot around this swelling fantasy of upward mobility, which intensifies and begins to fracture as Jane completes her book. She goes to her office on campus and runs into a fellow professor who, having returned from sabbatical without a book, was punished with a horrible teaching schedule. The colleague, who appears to be unhoused, sleeps at the school, a sight so disturbing to Jane that she runs away. When Jane returns home and adds another character to her book, the act reads as a rejection of her colleague’s fate.

After she finishes it days later and sends it to her agent, she starts to celebrate before she even hears back. She begins wearing the clothes of their hosts, as if she can attain wealth through osmosis. As she has “long and complicated” sex with Lenny, she imagines a past version of herself “outside in the garden, her face pressed against the glass, watching,” one of many doublings of her consciousness. And she throws Ruby a birthday party they can’t afford, hiring a magician and buying an expensive doll. She even takes the family to an open house in Multicultural Mayberry, despite the house “being way out of their price range, given that their price range was zero.”

Her delirious optimism becomes a kind of double vision that overwrites the city’s landscape and history like a power-drunk architect:

Gone was the suburban wasteland of Glendale and the trashy mini-mall sprawl of Mid-City. Gone was the relentless existential hum of the freeway, the racial blight of the LAPD, the handsome lying face of O.J. Simpson and the blank, bewildered face of his murdered wife, Nicole. Gone was the banally evil face of Mark Fuhrman and the nihilistic cokehead teens of Less than Zero. Gone were the Menéndez brothers and the white vigilante Michael Douglas played in Falling Down.

This tableau of real and fictional people, events, and places highlights Jane’s fanciful state of mind. When it all comes crashing down after her former editor declines to take on the book—a 150,000-word saga that hilariously links Zoë Kravitz, the Melungeon people of nineteenth-century Tennessee, and O.J. and Nicole Simpson’s kids—what should be a routine experience of rejection becomes world-ending. So she chases an even rosier world: television.

The contradictory allure of television is a fixture of Senna’s fiction. In New People, the main character recounts “Cosby night,” a weekly event when the members of her college dorm would watch the sitcoms The Cosby Show and A Different World. “It was such a sad relief to see these images, in such sharp contrast to the insidious television Negroes of their youth,” the character reflects, the collective happy to see better images of Black people but not actually impressed by the storytelling.

The quirky Black couple of “Resemblance” also have a Cosby

habit, despite them both hating the show. “I think now, looking back on it, we were in some strange way defending our right to exist as a well-to-do black family,” the narrator says. “Because the world outside our door … insisted we were just another interracial couple with a butterscotch baby…. But at night, in the privacy of our lair, we were that strange rare bird called a black family that squawked and flitted across the screen.” For Senna’s characters, representation is satisfying despite its emptiness.

Jane and Lenny initially have a less fraught relationship to Black television. After putting the kids to bed early in their marriage, “they could be their true selves” and watch “Trash. Black trash. Chitlin’ Circuit stuff. What Lenny called ‘colored television.’” But that sense of indulgence is lost once Jane aspires to become a television writer. Scared that she’ll lose Lenny’s respect as an artist, and convinced she’s being pragmatic, she pursues the career like an affair, expanding her double vision into a shaky double life.

Her desperation is funny and cutting. She finesses her way into a meeting with a Hollywood agent and offers a ridiculously bare pitch: “I want to write a comedy about … mulattos.” Somehow she ends up embedded with Hampton Ford, a loaded Black superproducer with a multimillion-dollar network deal. He made his name on a show that was “kind of a reboot of Diff’rent Strokes but with the races reversed,” which sounds awful, but for Jane he represents a golden ticket. “Jane watched him,” Senna writes, “thinking how all the things he’d brought into the room with him were things she’d like to have in her life, or at least in her vocabulary: egg-white omelet, green smoothie, trainer, assistant.” In his presence, her vague pitch becomes goofier, metastasizing like her doomed novel: “Not an interracial couple—that’s last century’s news, you know. But a pair of grown-up mulattos who have married each other and have given birth to two second-generation mulatto kids. Mulatto squared.” You can practically hear Senna giggling to herself as the “mulattos” multiply.

Absurdly, Hampton likes the pitch, and counters Jane’s magical thinking with even grander nonsense: “This could be the greatest comedy about mulattos ever to hit the small screen…. The Jackie Robinson of biracial comedies.” “You all deserve it,” he says of mulattos. “I mean, this is America. Everybody deserves a show about people like them, right?” Jane agrees and hitches her wagon to Hampton, a choice that plunges her into a world even hazier than those of book publishing and adjunct academia. In kind, her lies and her dreams grow in scope.

Colored Television slowly dilates into a fever dream as expansive as the Los Angeles metropolis. Shadowing Hampton as they workshop a pilot puts Jane in proximity to milieus even glitzier than those of her vacationing rich friends. She rides in his electric Porsche, she takes Percocets with him and his two assistants during a writing session, and she dines with him at an Italian restaurant that features valet parking and a “crowd that was low-key glamorous, shaggy, golden, vaguely famous,” all the while telling Lenny she’s just doing research for a new character in her book.

Senna’s prose ripples with images of reflection, doubling, and hallucination. A mirror in a home they tour, “through some trick of angles,” fails to show Jane’s reflection. A hotel Jane and Lenny visit to lessen their growing distance features a “phantom television” inside a mirror. Critical portrayals of television often present the medium as hypnagogic and pacifying, but Senna presents Jane’s psychic fracturing as enlivening, slickening. “She felt like a different person in so many ways now. Like an improved Jane,” Senna writes.

At one point, the mulattos of Jane’s novel and her pitch sessions with Hampton seem to blip into the real world. In one of the book’s funniest and most engrossing passages, Jane takes notes as Hampton tells her the bizarre story of attending a Kardashian birthday party and losing his child amid white women and their biracial kids. As he stares at a circle of singing children, he thinks, “Jesus Christ, is there a single kid at this party who is not a goddamn biracial? I’d take a white kid at this point, a fucking Korean kid. But it’s all biracial.” The rant is bizarre, and subtly layered. It’s both the kind of thing a eugenicist might say, and a legitimate sociological observation: Why do some spaces seem to produce mixed families rather than just have them?

Jane’s nine years of mulatto research should equip her to ponder this odd habitus and to question why the world she thirsts for is so devoid of Black women. But she’s too focused on maintaining her double life and finding a pilot idea that pleases Hampton to be self-aware. So she plows forward, ignoring red flags like the fact that she has never actually formalized her arrangement with Hampton. That oversight results in a big twist that isn’t quite as jarring as the many turns in New People, which molts every few chapters. But Colored Television offers a wider sandbox for Senna’s observations about class, race, and place. Senna departs from the fatalistic noir mood that often characterizes stories about Hollywood and its tragic suckers, dwelling instead on the more mundane indignities of living adjacent to but not among the ultrarich: the lack of decent housing, the subpar food, the clunkier cars, and rattier clothes.

The status-obsessed language of this echelon is also grating. One of Hampton’s favorite words is “prestige,” a quality that Jane’s show ideas often lack. The producer drives the word into the ground, using it as shorthand for significance and depth without ever defining it. That strange, empty language conveys his lack of taste, but also lures Jane in. It, like mulatto, like representation, has an almost televisual quality. It often means nothing, but from the right angle, there’s a flicker of recognition.