Did the Student Encampments Accomplish Anything?

Mohammad Yassin’s parents had warned him away from politics. His father grew up in Lebanon during the civil war, when having the wrong opinion could get you killed. Yassin, who is Palestinian American, arrived at the University of Toronto four years ago with the intention of studying economics and statistics. He felt that Canada wasn’t his permanent home, and he distrusted existing political institutions, so he avoided involving himself in activism or student government. “I just kind of was like: Hey, I’m gonna put my head down and just study for my entire degree,” he told me, chain-smoking cigarettes in a keffiyeh and sunglasses.But when Hamas viciously attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, everything changed. Later that month, a group called U of T Conservatives organized a rally on campus to display “unwavering support for Israel against Hamas terrorism.” By then, Israel had begun its brutal war on Gaza, and word spread among Yassin’s peers that a counterprotest should be organized. Student groups supporting Palestinians were once vibrant on campus but had diminished in recent years, particularly since Covid. Yassin, who has a sardonic sense of humor and a calm demeanor, joined the counterrally, which drew around 200 people. Many were inspired to organize on an ongoing basis.After months of walkouts, rallies, and cultural events in support of Palestinians, on April 1, 26 students clad in keffiyehs and masks occupied Simcoe Hall, the seat of governance at the University of Toronto, demanding that the school divest from holdings in companies complicit in Israel’s siege. After 30 hours, they left, following an agreement to meet with the university president.The meeting, however, failed to satisfy them. A little over two weeks later, some 500 miles southeast, hundreds of protesters occupied the South Lawn of Columbia University. The pitched tents and mass of demonstrators were a lifeline for the Palestinian groups at U of T, who, like student groups around the world, took the Columbia encampments as inspiration for the next phase of their movement. Anticipating Yassin and his allies’ next move, U of T put up fencing along part of its campus called King’s College Circle, a patch of green space that had recently been renovated. But on May 2, Yassin and about 50 others with U of T Occupy for Palestine set up camp anyway, breaching the fence in the middle of the night. Soon allies just started showing up. “The first day was magical,” Yassin recalled. The group demanded that the university disclose its investments and divest from companies and universities associated with Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land. The school warned the students that they were trespassing on private property. Yassin’s group expected the university to expel them at any moment, certainly within a few days.But that didn’t happen. Toronto police declined to arrest the protesters, so at the end of May, U of T sought a court order to force the issue. For more than two months, the People’s Circle for Palestine operated as a miniature village in the heart of Canada’s largest city. Weeks after almost all encampments on campuses in the United States had been disbanded—Columbia’s lasted just under two weeks—this one continued to operate. Around 200 tents were pitched at one point or another, and many residents, like Yassin, slept there almost every night, returning home only to do some laundry or get the occasional decent rest.On July 2, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice finally granted the university’s injunction to clear out the encampment, which had lasted 62 days. Hours later, Yassin stood with other protest leaders to announce to the news cameras and journalists that they were disbanding the mini-village ahead of the deadline the next evening. That would enable them to leave on their terms and avoid being brutalized by police, he said. Behind him, tents with slogans written on them were still up. “This legal maneuver changes nothing,” he announced defiantly. “Make no mistake, our resolve is stronger than ever. We’ve said from day one that we will not leave this campus until U of T discloses, divests, and cuts ties. That commitment stands firm.”Soon after Yassin spoke, protesters began taking down the many signs on the fence surrounding the encampment. By 6 p.m. the next day, little evidence of the encampment remained, outside of people posing for photos in front of a papier-mâché olive tree with anti-Zionist slogans spray-painted on it. As the sun set, a man and a woman wearing an Israeli flag toppled the structure.The campus rallies against Israel constituted the largest protests at North American universities in the twenty-first century. According to the Crowd Counting Consortium, encampments were erected at more than 130 campuses, and many protests erupted at schools even before Columbia’s tents went up. In the United States, more than 3,600 people were arrested or detained during these campaigns. Encampments eventually spread to Aus

Mohammad Yassin’s parents had warned him away from politics. His father grew up in Lebanon during the civil war, when having the wrong opinion could get you killed. Yassin, who is Palestinian American, arrived at the University of Toronto four years ago with the intention of studying economics and statistics. He felt that Canada wasn’t his permanent home, and he distrusted existing political institutions, so he avoided involving himself in activism or student government. “I just kind of was like: Hey, I’m gonna put my head down and just study for my entire degree,” he told me, chain-smoking cigarettes in a keffiyeh and sunglasses.

But when Hamas viciously attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, everything changed. Later that month, a group called U of T Conservatives organized a rally on campus to display “unwavering support for Israel against Hamas terrorism.” By then, Israel had begun its brutal war on Gaza, and word spread among Yassin’s peers that a counterprotest should be organized. Student groups supporting Palestinians were once vibrant on campus but had diminished in recent years, particularly since Covid. Yassin, who has a sardonic sense of humor and a calm demeanor, joined the counterrally, which drew around 200 people. Many were inspired to organize on an ongoing basis.

After months of walkouts, rallies, and cultural events in support of Palestinians, on April 1, 26 students clad in keffiyehs and masks occupied Simcoe Hall, the seat of governance at the University of Toronto, demanding that the school divest from holdings in companies complicit in Israel’s siege. After 30 hours, they left, following an agreement to meet with the university president.

The meeting, however, failed to satisfy them. A little over two weeks later, some 500 miles southeast, hundreds of protesters occupied the South Lawn of Columbia University. The pitched tents and mass of demonstrators were a lifeline for the Palestinian groups at U of T, who, like student groups around the world, took the Columbia encampments as inspiration for the next phase of their movement. Anticipating Yassin and his allies’ next move, U of T put up fencing along part of its campus called King’s College Circle, a patch of green space that had recently been renovated. But on May 2, Yassin and about 50 others with U of T Occupy for Palestine set up camp anyway, breaching the fence in the middle of the night. Soon allies just started showing up. “The first day was magical,” Yassin recalled. The group demanded that the university disclose its investments and divest from companies and universities associated with Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land. The school warned the students that they were trespassing on private property. Yassin’s group expected the university to expel them at any moment, certainly within a few days.

But that didn’t happen. Toronto police declined to arrest the protesters, so at the end of May, U of T sought a court order to force the issue. For more than two months, the People’s Circle for Palestine operated as a miniature village in the heart of Canada’s largest city. Weeks after almost all encampments on campuses in the United States had been disbanded—Columbia’s lasted just under two weeks—this one continued to operate. Around 200 tents were pitched at one point or another, and many residents, like Yassin, slept there almost every night, returning home only to do some laundry or get the occasional decent rest.

On July 2, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice finally granted the university’s injunction to clear out the encampment, which had lasted 62 days. Hours later, Yassin stood with other protest leaders to announce to the news cameras and journalists that they were disbanding the mini-village ahead of the deadline the next evening. That would enable them to leave on their terms and avoid being brutalized by police, he said. Behind him, tents with slogans written on them were still up. “This legal maneuver changes nothing,” he announced defiantly. “Make no mistake, our resolve is stronger than ever. We’ve said from day one that we will not leave this campus until U of T discloses, divests, and cuts ties. That commitment stands firm.”

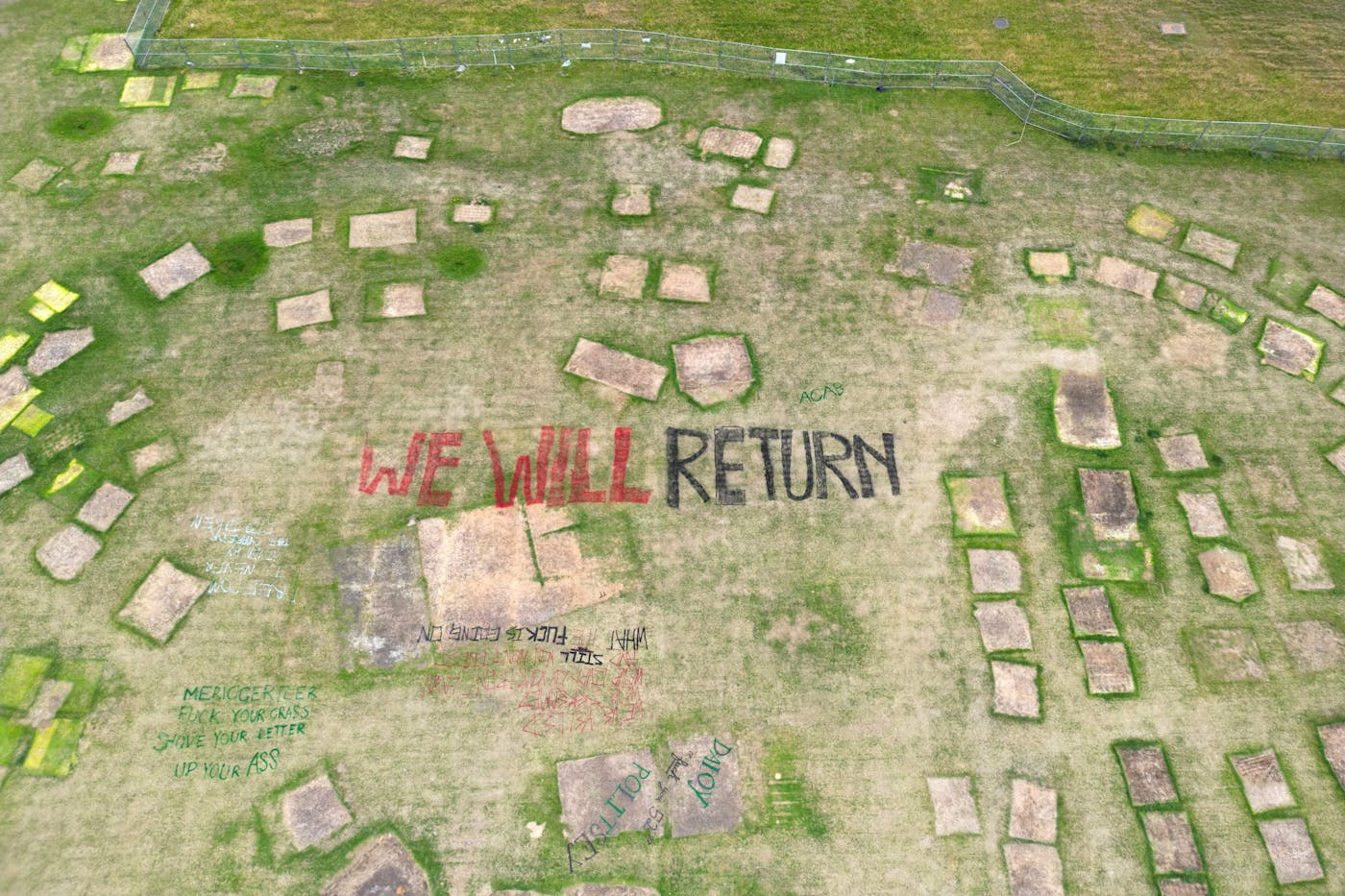

Soon after Yassin spoke, protesters began taking down the many signs on the fence surrounding the encampment. By 6 p.m. the next day, little evidence of the encampment remained, outside of people posing for photos in front of a papier-mâché olive tree with anti-Zionist slogans spray-painted on it. As the sun set, a man and a woman wearing an Israeli flag toppled the structure.

The campus rallies against Israel constituted the largest protests at North American universities in the twenty-first century. According to the Crowd Counting Consortium, encampments were erected at more than 130 campuses, and many protests erupted at schools even before Columbia’s tents went up. In the United States, more than 3,600 people were arrested or detained during these campaigns. Encampments eventually spread to Australia, Western and Northern Europe, Latin America, and Asia, including even Israel itself, where some students erected a tent at Bezalel Academy, an art school.

But by the summer, most of the protests had disappeared along with the tents, either removed by police or disbanded for the summer break. The Israeli government continues to kill thousands of Palestinians with little compunction, and the Biden administration continues arming it. Yassin is still worried about his family in Lebanon and his mother’s extended family in Gaza. Students who participated in the protests, allies who supported them, and critics who derided them as antisemitic are all left wondering: What did the once-in-a-generation mass protests accomplish? How will they influence the activism that may resume when the new academic year begins?

Canada has typically had smooth relations with the Jewish state, but in the twenty-first century, the conservative government of Stephen Harper took it to a new level, marching in lockstep with Israel. That history of support is one reason that concern for Palestine has become commonplace on the left in Canada. And not just in Canada, obviously. Not since South Africa in the 1980s has a people captured the left-wing imagination as a symbol of global injustice. The irony is that this phenomenon is something of a reversal; Zionism was once considered a uniquely heroic cause among many of American left-liberalism’s most exalted figures. According to historian Eric Alterman, author of We Are Not One: A History of America’s Fight Over Israel, liberals and leftists from Eleanor Roosevelt (“The Jews in their own country are doing marvels and should, once the refugee problem is settled, help all the Arab countries,” she wrote) to Progressive Party leader Henry Wallace to Freda Kirchwey, editor of The Nation, saw Jews in Palestine as anti-imperialists battling the British Empire, which was manipulating the Arab states and squaring off against the Soviet Union with little care for the fate of Jews.

From the 1940s until 1967, the Palestinians had few advocates in the Western world. They were still recovering after being driven out of their villages by Israel in 1947–1949 during the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” the Arabic term for the dispossession of Palestinians. “It’s very hard to organize politically when you don’t even have a roof over your head,” said Yousef Munayyer, a senior fellow at Arab Center Washington DC. Partly as a result, the myth that Palestinians left their homes voluntarily predominated in the United States.

The 1967 Arab-Israeli War created a groundswell of support for Palestinians in the United States for the first time, particularly among radical Black intellectuals and activists. As Alterman explains, the Palestinians began to be seen as a “Third World nation,” deserving of sympathy like other non-Western peoples. But pro-Palestinianism remained a minority viewpoint in the civil rights movement, as more mainstream leaders like Martin Luther King and Bayard Rustin and organizations like the NAACP and the National Urban League issued statements in solidarity with Israel. In the 1970s, Palestinians garnered little institutional backing beyond the furthest left of groups, such as West German terrorists. “We have been unable to interest the West very much in the justice of our cause,” the Palestinian American literary critic and activist Edward Said lamented in his 1979 book, The Question of Palestine. That same year, when President Jimmy Carter secured a peace deal between Egypt and Israel, Palestinians’ anger at having their concerns ignored did little to dilute celebrations in the United States. But at the grassroots level, support for Palestinians had been emerging. It deepened during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon and especially after the massacre at the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. It grew again with the first intifada, which began in 1987, and has since “grown gradually over time,” Alterman observed.

Today, for people under 30 and those on the left around the world, Palestine has become a defining issue. Erin Mackey, who graduated from U of T this year, is a prime example. A Canadian American from Boston who came to Toronto because its university was cheaper than those in the states, she was active in campaigns to encourage the administration to divest from fossil fuels, which U of T announced it would do in October 2021. Mackey has the message discipline of a seasoned politician and is as polite in private as she is confrontational in public. The day we met, she was wearing overalls, her nails painted bright red. She sees a natural evolution from agitating against climate change to agitating against Israel. “I saw the links between climate justice and Palestinian liberation,” she explained, referring to Israel’s environmental destruction and its confiscation of land and water. In late October 2023, she and other activists began targeting the Royal Bank of Canada for both its funding of fossil fuel companies and its investments in the U.S. company Palantir, which sells AI surveillance technology to Israel. Once Arab and Palestinian students decided to construct the encampment, they asked Mackey, as someone trained in media outreach, for help. She soon became one of the most visible spokespeople for U of T Occupy for Palestine. “As someone who isn’t Palestinian, knowing my tuition dollars are going toward the genocide is horrifying,” she told me when we spoke at the encampment.

The demographics at U of T Occupy for Palestine are suitably reflective of the changed landscape. Both Mackey and Yassin estimated that Palestinians or other Arabs made up only 60 percent of the people who were at the encampment; the remaining 40 percent were other people of color, Jews, and white leftists. A group called Jews Say No to Genocide maintained a constant presence, hosting weekly Shabbat dinners and absorbing the slurs of pro-Israel Jews who staged a counterprotest. The intellectual/activist Naomi Klein showed up once. But many of the signs and tents contained writing attesting to the personal connections individuals had with people in Gaza, citing relatives who have died or castigating Arabs for not sticking together. One encampment resident has had an unimaginable 26 members of their family killed in the Gaza Strip in the past year. “We’re not spectating,” Yassin said.

If nothing else, the 2023–2024 protests showed that the constituency for the Palestinian cause has broadened significantly beyond the Arab- and Muslim-majority countries to which it was once confined. What’s more, the plight of the Palestinians has managed to push tens of thousands of people to publicly demonstrate in solidarity, sometimes at great personal risk and in violation of laws and school policies. “That signals not just a growth in the scale and scope of this thing, but also the depth of commitment to the cause, which, again, is at a new and unprecedented level,” Munayyer said. While conservatives and many Democratic Party politicians deride Palestinians as a nonexistent people, uniformly antisemitic, or congenitally prone to terrorism, such designations no longer have mass appeal beyond the right wing and an aging subset of Democrats.

Younger generations, especially, see Israel’s repression as a straightforward question of right and wrong. Pew Research Center found that the number of adults under 30 who sympathized with Palestinians was twice the number who sympathized with Israelis, and the number who say the way Israel is fighting its war against Hamas is “unacceptable” is more than twice the number who say it’s “acceptable.” Young people have a more positive view of Palestinians than of Israelis, and the number who say Hamas’s reasons for fighting Israel are valid is slightly higher than the number who say they are not (notably, however, 58 percent of young people said Hamas’s October 7 massacre was unacceptable). Just 16 percent of young people favor the United States providing military aid to Israel. For Palestinians, who were once synonymous with terrorism in the Western imagination, this widespread support marks a staggering shift. The students holding signs and chanting in unison might eventually be seen as a harbinger of a changed Western approach to the role of Palestinians in the Middle East.

But the levels of participation in protests over the last year should not be exaggerated either. For all the attention they received—and for all the anxiety they provoked among conservatives and in the Jewish establishment in the United States—only 8 percent of college students took part in demonstrations in support of either Palestinians or Israelis, according to a Generation Lab survey published on May 7. The Vietnam War–era protests with which the encampments have been compared far outstripped these figures and lasted for years. In May 1970 alone, more than four million students at around 900 campuses went on strike after National Guardsmen gunned down four students at Kent State University. The Gaza encampments “were really centered around student communities and the people you would be expecting to engage in these campus uprisings,” said Lisa Mueller, a political scientist at Macalester College who studies protest movements. The Vietnam antiwar movement “far transcended students and people on the left.” Moving beyond protests that are largely drawing on the left would signal to potential supporters and elites that the movement can be a force for a pressure and not just confined to a fringe, but it remains to be seen whether the pro-Palestinian elements in the West can make it happen.

Similarly, while young people are more sympathetic to the plight of Palestinians than their older counterparts are, they are generally less likely to be politically active and engaged than their elders, rendering their sentiments less impactful. People who are under 30 years of age vote in smaller numbers than their elders, feel less informed about candidates and issues than others, believe they’re unqualified to participate in politics, donate less money to political campaigns, and run for office in far fewer numbers. And while young people hold far more pro-Palestinian sentiments than others, that does not necessarily translate into a concentrated bloc powerful enough to alter U.S. policy. The same polls showing the sea change in how younger generations perceive the Israeli- Palestinian conflict reveal that they care most about the same issues that older people do: the cost of living, access to good-paying jobs, and preventing gun violence. “Particularly in a democratic society, there are electoral pressures for elected leaders and candidates to heed the demands and grievances of diverse potential voters,” Mueller said. “I haven’t seen that happen so much yet.”

Of course, the usual apathy and cynicism of younger voters are precisely what make the campus protests so unusual. Every organizer knows how difficult it is to get people into the streets for an afternoon, let alone for days or weeks. On day 56 of the camp, Mackey told me, “I don’t think anybody thought we would get here.” After negotiating with the administration the first week, U of T Occupy for Palestine settled in for a long haul. They got trespassing notices and were threatened with expulsion and suffered through rainy nights, hail, and extreme heat. Still they stayed. “This is just a piece of a much broader movement,” Mackey said.

Indeed, when Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris selected Minnesota’s Tim Walz as her running mate in August, there was wide speculation that she had passed over Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro because of his insulting comments about the protesters and his arguably greater fondness for Israel. If this calculation played a role in Harris’s choice, it would mean the students had influenced politics at the highest level.

At U OF T Occupy for Palestine, five people sat on chairs at the entrance, screening people going in and out. “You Are Entering The People’s Circle For Palestine,” a sign read. One tent held a library with a few hundred books; other tents served variously as the kitchen, a space for art, and a prayer room. Solar panels generated energy for phone chargers. The camp lasted so long that some participants left for trips abroad and returned to a still ongoing project. At the final rally after the encampment was dismantled, about 2,000 Torontonians marched downtown to celebrate and mourn what had unexpectedly lasted for two months. “We galvanized an entire city,” Yassin told me. “We opened a lot of people’s eyes.” Mackey, similarly, believes that the protests persuaded some students who were either indifferent or hostile to the Palestinian cause. “I’ve seen it in my own life,” she told me. “The divide is definitely closing against genocide.”

The Gaza encampments garnered copious media attention. As University of California at Berkeley political scientist Omar Wasow said, the “campus protests elevated the issue of the war in Gaza and some of the inequities in the war onto the national agenda.” This is no small thing, because even as Israel kills unfathomable numbers of Palestinians—more than 40,000 at the time of this writing—it is easy to imagine the slaughter falling off the front pages. “They’ve succeeded in raising consciousness broadly in America and Canada among everyday citizens who may not be following the war in Israel and Palestine closely,” argued Mira Sucharov, a political scientist at Carleton University in Ottawa.

But attracting attention to a cause is not the same thing as persuading people of its justice, let alone its urgency. On the level of broader public opinion, the number of Americans who opposed the Gaza student protests was twice the number who supported them, and the vast majority of survey respondents backed Israel over Hamas. Even worse, a poll conducted in mid-June found that Americans were as likely to say the protests made them sympathize less with the Palestinians than to say the opposite. In March, the Canadian government halted arms sales to Israel after Parliament passed a nonbinding resolution, but this was before the U of T encampment began. Canadians were no friendlier to the campus protests than Americans were. Generally speaking, the encampments raised public awareness of the huge numbers of deaths in Gaza, but that didn’t translate into encouragement or assistance to the cause.

Of course, protests can galvanize change even when unpopular. But they can just as easily be ignored, contained, or trigger a backlash. That reality is one of the risks protesters take when they employ maximalist rhetoric. U of T Occupy for Palestine was constructed to accommodate small tents, but it was unconcerned with building a larger one. The fence that encircled King’s College Circle was plastered with signs, some of which testified to the immense violence that Israel has unleashed in Gaza, quoting Palestinian children who have been orphaned, or referencing mothers who have been made childless. Other posters simply had drawings of Palestinian flags or declarations of solidarity from non-Palestinians. Such placards might be divisive, but they can’t reasonably be perceived as dangerous.

Other signs were more ambiguous, praising Palestinian “martyrs” and calling for a “student intifada.” These could be read as calls for indiscriminate violence of the kind Hamas perpetrated on October 7, or they could be considered, as organizers claim they are intended, as general (but not necessarily violent) cheers for rebellion. And indeed, polls showed that slogans were heard differently by different audiences. Two-thirds of Jewish university students heard the ubiquitous chant “From the River to the Sea” as calling for the expulsion and genocide of Israeli Jews, while only 14 percent of Muslim students heard it that way, according to a University of Chicago poll. The Muslim students believed it was a chant for the equality of Jews and Palestinians in one state, or for a two-state solution. While the forcefulness and vagueness of these pro-Palestine slogans may seem sinister to some, the reality may be more banal. “It’s a matter of wanting to be concise,” Sucharov told me. “It’s a matter of wanting to center the Palestinian experience.” In the same way that some people incorrectly perceive the slogan “Black Lives Matter” as suggesting that other human lives are less valuable, so do Palestinians use slogans with meanings they understand but that may be unclear or offensive to others, she said.

Of course, one difference is that some elements of Hamas do mean the slogans in the darkest possible sense, hoping for more violence against Israeli civilians to the point that the state itself is destroyed and its people either subjugated, expelled, or killed. In his ruling granting the University of Toronto the injunction to remove the encampment, the Ontario Superior Court judge absolved the organizers of antisemitism. “The automatic conclusion that those phrases are antisemitic is not justified,” he wrote about the ambiguous phrases. These determinations by the court were greatly appreciated by U of T Occupy for Palestine, which had routinely been accused of being a hate-fest. (One professor had written in Canada’s National Post newspaper that “the encampments are led by pro-Hamas advocates who are seeking to justify Islamist terrorism by normalizing antisemitism.”)

But while the ruling absolved the organizers of antisemitism, it also clarified that at rallies where pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel protesters squared off, unambiguously antisemitic phrases were directed at Jews. These included comments such as “Death to the Jews,” “We need another holocost [sic],” and “Jews belong in the sea.” The judge noted that none of those comments were uttered by organizers like Yassin or Mackey, nor even any of the encampment occupants, but community members who were adjacent to the encampment. Organizers erased antisemitic phrases when they were written in chalk outside the camp. But the reality is that excising antisemitic elements is a constant requirement for pro-Palestinian activists and will grow increasingly important as the movement attracts new adherents, some of whom will inevitably want to target Jews. Again and again at protests against Israel’s destruction of Gaza, antisemitism reared its ugly head. The presence of bigotry at these events suggests how easily demands for unnamed forms of rebellion can shade into justifications for violence.

Antisemitic acts skyrocketed in Canada in late 2023 and 2024, as they did in the United States and around the world. In Toronto, synagogues, businesses, and day schools were defaced with graffiti, a synagogue was set on fire, and Jewish students reported rampant antisemitism at U of T and other schools. U of T Occupy for Palestine wasn’t responsible for these acts, which terrified much of the Jewish community and influenced how the public perceived the protests, and the organizers didn’t seem to care much about any of that. The tents inside the encampment had catchphrases like FUCK ALL ZIOS written on them, short for “Zionists.” But there is a thin line between opposing Zionism and cultivating hatred against Zionists, and such rhetoric thins the line even more. In our conversation, Yassin spoke fondly of the Jews who joined him in supporting Palestinian liberation, as did other organizers. But he pushed back against the idea that the protesters should modify their rhetoric to appeal to anyone doubtful of the Palestinian cause or fearful for Zionist Jews. “It’s more important to maintain the purity of the message,” he said. He cited boxing legend Muhammad Ali’s refusal to participate in the Vietnam War when drafted (“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” he famously said as U.S. troops were fighting them) as an example of how a once-shocking message can later be seen as prescient. In the coming years, Yassin argued, it will become more acceptable to publicly castigate Zionism and Zionists. “Calls for justice are not hatred,” he said.

One way in which the pro-Palestinian movement differs from activism against South African apartheid, the Vietnam War, and discrimination against African Americans is that its target, Israel, is also a refuge for a persecuted people and their lone nation-state. Another way is that, so far at least, organizers appear indifferent to how their rhetoric and actions are interpreted by the broader public. Yassin and others are convinced that history is on their side, and that public opinion—and government policy following it—will inevitably swing their way. As Mackey put it about the university divesting from Israel, “It’s when, not if.”

This line of thinking absolves activists of pursuing alternative strategies that might be more beneficial, such as allying with Israel’s leftists, clarifying the place of Jews in a free Palestine, denouncing all deliberate attacks on civilians, or engaging in self-criticism that could perhaps help propel the movement forward. Mackey observed that the divestment campaign at the University of Toronto began in 2006. But in 2024, the school is no closer to meeting the movement’s demands than it was 18 years ago. The U of T encampment disbanded without compelling the school to make any changes.

Some campuses had victories. At Brown University, students took down their tents when the school’s governing body agreed to vote on a proposal to divest the school’s $6.6 billion endowment from companies affiliated with Israel. “Not only did we force the administrators to come to the table, but we also forced them into accepting a really historic vote,” a Brown encampment participant told reporters at the end of April. “Today we’re seeing the results of negotiations that didn’t seem possible even a week ago.” As far away as Ireland, student protesters caused Trinity College Dublin to divest from Israeli firms. At Macalester College in Minnesota, where Mueller teaches, a task force has been organized to deal with the long-term grievances of students. “Putting campus investment practices on the long-term agenda is probably going to have a decent tail,” she said.

But these were the exceptions. From Columbia University and other Ivy League schools to smaller campuses in the United States and around the world, by and large, the students failed in their basic objectives of ending U.S. support for Israel or forcing most universities to divest from it.

For now.

When students return for the 2024–2025 academic year, activism may resume at a high level, after organizers have licked their wounds and recharged their energies. Mackey and Yassin are adamant that their struggle is far from over, and that they are inspired by their successes, such as they were. “I don’t think that this moment of heightened student protest, for Palestinian freedom on college campuses, has ended yet,” Munayyer of the Arab Center Washington DC agreed. The day after the judge issued the injunction that finished the U of T encampment, one spokesperson said at a press conference, “We are just getting started. This encampment is one of many tactics.”

Ultimately, the most concrete impact of the Gaza protests may be in educating a new generation of activists. Tens of thousands of students participated in mass demonstrations against Israel, encounters that may be formative for decades to come. Mackey’s experiences in climate activism contrasted with her pro-Palestinian activism. In April 2023, she and 200 other student activists occupied a building on campus demanding U of T divest from fossil fuel companies; the students stayed for 18 days. But authorities handled that situation very differently. “We weren’t threatened by police,” she said. At U of T Occupy for Palestine, individuals hurled slurs at her and the other students and played music at night to disrupt their sleep. She, Yassin, and other organizers were physically exhausted by showing up each day for two months to arrange logistics for hundreds of people: providing food, disposing of waste, cleaning, dealing with press, negotiating with lawyers and the school administration, dealing with hostile counterprotesters, and hosting community meetings. A tent where coffee was served blew away in the wind at one point. It was draining and stressful to manage these tasks, but the experience was also indispensable in training a generation of activists. Mackey said the connections that Palestinian solidarity groups have made with labor and faculty organizations will be lasting. Research shows that individuals who participate in protests can be profoundly changed by the experience, altering their family and career choices, along with their political trajectories and voting patterns. A study from Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement found that large-scale protests of the kind following George Floyd’s murder by police in 2020 brought new people into the political process at a higher rate than smaller-scale demonstrations.

Yassin told me that he has been emboldened to pursue a career in humanities rather than the safer choice in finance to which he had resigned himself. The support and media attention the encampment received were far greater than anything he or his allies expected, convincing him to envision a better future for himself personally as well. He plans to continue in political organizing in some fashion. “If I learned anything from the camp, it’s that anything is possible,” he said. Mackey has likewise been encouraged by her two months in the encampment. She starts a job soon at an environmental nonprofit and will continue to be involved in organizing on and off. Seeing so many people show up in solidarity with Palestinians “was a very profound and transformational moment,” she said. At the rally sending off the encampment, she was in tears.

On a rainy day in mid-July, a visibly more relaxed Yassin visited King’s College Circle for the first time since the encampments were dismantled two weeks prior. All traces of the protests were long gone: the tents, the tarps, the Palestinian flags. An orange plastic fence had replaced the wall that ringed the area, and the grass was growing back where it had been trampled by tents and foot traffic. “God, this is strange,” he said, gazing at the empty space where the small village existed for two months.

Yassin’s parents worried once he became an activist. But they grew proud of their outspoken son. When his mother visited the encampment, she cried, moved to see so many Palestinian flags displayed in one place. Yassin told me that he’s heartened that the Palestinian cause has gained acceptance over decades; he knows it has the potential to reach many more people. Even if the encampments don’t recur, other protests will follow in their wake. A religious man, he believes that in the long sweep of history, justice for Palestinians is likely. Even if Israel kicks every Palestinian out of their homeland, still they will not give up on returning. And, eventually, they will return. “All of this is still possible,” he said, walking on the grass.