Exiled Kazakh journalist dies after shooting in Kyiv, exposing global reach of authoritarian regimes

Aidos Sadykov, a Kazakh opposition figure who fled to Ukraine in 2014, died on July 2 after being shot in Kyiv. His murder not only strains Ukraine-Kazakhstan relations but also highlights the increasing vulnerability of political dissidents abroad, even in countries seen as safe havens.

Kazakh opposition journalist and blogger Aidos Sadykov died in a Kyiv hospital on 2 July 2024, two weeks after being shot in the head in an apparent assassination attempt. His wife, Natalia Sadykova, announced his death on Facebook, blaming Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev for her husband’s “martyrdom.”

The attack on Sadykov, a prominent critic of the Kazakh government, has raised concerns about the safety of dissidents and journalists in Ukraine and the reach of authoritarian regimes beyond their borders.

Sadykov’s journey from a local activist in Kazakhstan to an exiled journalist in Ukraine illustrates the risks faced by opposition figures in authoritarian regimes and the important role that countries like Ukraine play in providing refuge for political dissidents.

“Aidos gave his life for Kazakhstan, accepting a martyr’s death at the hands of killers,” Sadykova wrote. “For thirteen days, Aidos fought for his life in intensive care, but a miracle did not happen. His death is on Tokayev’s conscience.”

Kazakhstan denies extradition to Sadykov’s suspected assassins

Ukrainian prosecutors are now preparing to upgrade charges against two Kazakh citizens suspected in the attack from attempted murder to premeditated murder. The suspects, identified as Altai Zhakanbayev and Meiram Karatayev, fled Ukraine immediately after the 18 June shooting and are currently wanted by Interpol.

The assassination attempt took place in broad daylight in Kyiv’s Shevchenkivskyi district, where an unknown assailant shot Sadykov in the head while he was in a car with his wife. Sadykova told Radio Azattyk (the Kazakh service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) that she believed the shooter was a professional hitman.

Sadykov was rushed to the hospital and underwent surgery, but remained in a deep coma with minimal chances of recovery. On 24 June, Sadykova reported that doctors gave only a 0.01% chance of a positive outcome.

The incident has strained diplomatic relations between Ukraine and Kazakhstan. While President Tokayev initially offered to assist in the investigation, stating that Kazakh authorities were “ready to join the investigation to establish the truth,” Kazakhstan later refused to extradite the suspects to Ukraine.

On 22 June, one of the suspects, Altai Zhakanbayev, surrendered to law enforcement in Kazakhstan. The Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine requested the extradition of both suspects. However, on 27 June, Maulen Ashimbayev, speaker of the Kazakh Senate, stated that Kazakhstan would not hand over the suspects to Ukrainian law enforcement.

“Kazakhstan does not extradite its citizens to foreign states,” Ashimbayev said, citing the country’s constitution. This decision has further complicated the investigation and prosecution of the case.

Sadykov’s journey from Kazakh dissident to exiled journalist

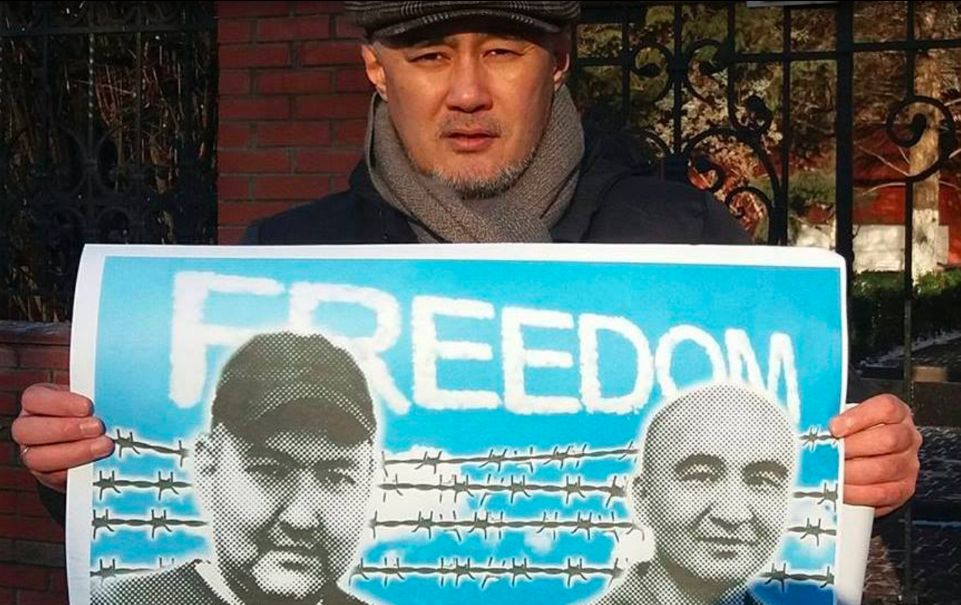

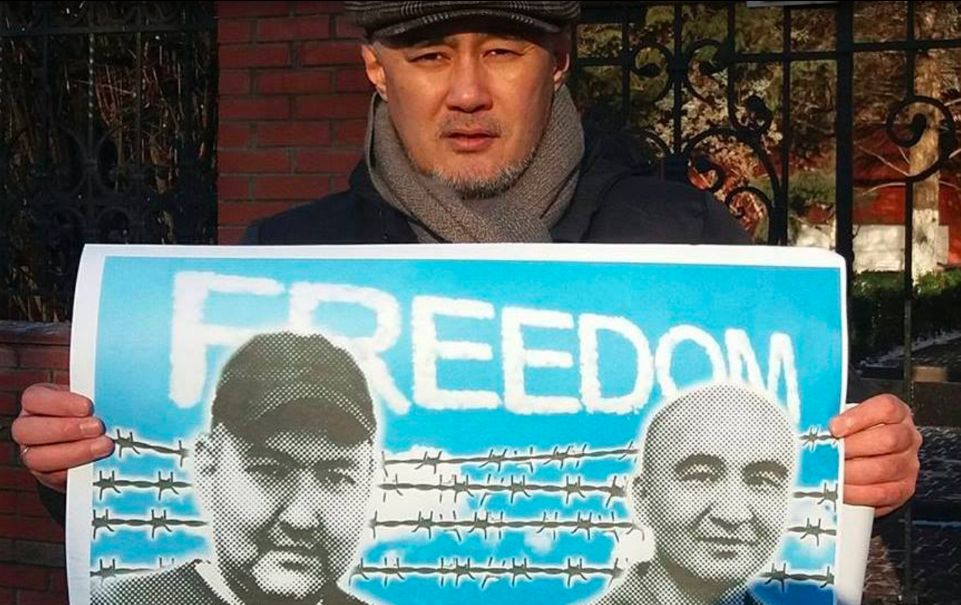

Sadykov and his wife had been living in Kyiv since 2014 after fleeing Kazakhstan due to political persecution. In Ukraine, they continued their opposition activities through their YouTube channel BASE, where Sadykov and his wife frequently criticized the Kazakh government and referred to President Tokayev as a “puppet of Russian influence.”

In their videos, the Sadykovs discussed protests and strikes in Kazakhstan, whether social, environmental, or political, and urged Kazakhs to join them. Journalists working in Kazakhstan helped BASE produce its materials.

Sadykov was born in the village of Karabutak in the Aktobe region of Kazakhstan, near the Russian border. He grew up in a linguistically complex environment, attending a Russian-language school while speaking Kazakh at home. “Those who spoke their native language were called barkhan – it sounded like mockery,” he told Kraina magazine shortly after moving to Kyiv.

In Kazakhstan, Sadykov was a well-known opposition figure, actively opposing then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev. He led the local branch of the All-National Social Democratic Party Azat in the Aktobe region, which was in opposition to Nazarbayev. Later, he co-founded the public movement Gasta.

Sadykov’s political activism intensified in 2010 when he participated in a protest demanding Nazarbayev’s resignation, the release of political prisoners, and opposition to land sales. This protest, which was not officially sanctioned by the authorities, led to several criminal cases being opened against him. The charges ranged from distributing counterfeit money to participating in fights and resisting police.

Following the 2010 protests, Sadykov was subjected to a month-long forced psychiatric examination. He was subsequently sentenced to two years in prison on hooliganism charges, which he maintained were fabricated.

Reflecting on his activism, Sadykov later said, “When you go to a protest, you have to be prepared for the worst – you can be beaten, arrested, killed. When they put handcuffs on me, I was calm. I understood that it was inevitable.”

During his imprisonment, Sadykov claimed that Kazakh special services attempted to recruit him. “They offered a separate room with a TV and telephone, an unlimited number of visits and parcels,” he recalled, insisting that he refused such “cooperation.”

After his release from prison, Sadykov’s troubles with the Kazakh authorities continued. In early 2014, the Kazakh government opened a case against his wife, who was also a journalist. This development prompted the family, including their two children, to leave Kazakhstan and settle in Kyiv in April 2014.

In Ukraine, Sadykov became known as a journalist and the head of the internet media outlet BASE. In media appearances, he criticized the current President of Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, accusing him of holding pro-Russian positions.

The journalist was known for supporting the January 2022 protests in Kazakhstan, which were suppressed with the help of troops of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a Russian-led military alliance that also includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

In October 2023, Sadykov was placed on a wanted list in Kazakhstan for allegedly “inciting social, national, tribal, class, or religious hatred.”

Despite living in exile, Sadykov and his wife continued to face pressure from Kazakh authorities. In autumn 2023, both Aidos and Natalia Sadykov were placed on a wanted list in Kazakhstan, accused of allegedly inciting hostility.

Even then, he viewed Kyiv as “the center of democracy in the post-Soviet space, from where the offensive against other regimes will begin,” noting that the Ukrainian capital had long been a gathering place for opposition figures from Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Georgia, and Azerbaijan.

Kazakh opposition under pressure as Tokayev leans towards Russia

The political landscape in Kazakhstan has been characterized by significant repression and limited freedoms for opposition figures, a trend that has persisted from Nursultan Nazarbayev’s long tenure to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s current presidency.

Despite some promises of political reform, opposition leaders and activists face severe crackdowns, long prison sentences, and frequent detentions.

Under both Nazarbayev and Tokayev, the government has maintained tight control through legal mechanisms, political maneuvering, and suppression of dissent. Opposition leaders have faced arrest, exile, or worse. Media and civil society operate under strict limitations, with critical voices often silenced through harassment or legal challenges.

Key opposition figures, such as Marat Zhylanbaev and Zhanbolat Mamay, have been targeted with heavy charges. Zhylanbaev, head of the unregistered “Alga, Kazakhstan!” party, has been charged with financing extremist activities and participating in a banned extremist organization, facing up to 12 years in prison. His trial was closed to the public, and the authorities claimed the need to protect witness security as the reason for this decision. Similarly, Mamay, leader of the Democratic Party of Kazakhstan, received a suspended six-year sentence on charges related to organizing mass riots and insulting law enforcement officers.

Despite initial hopes that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might push Kazakhstan towards the West, the country’s ties with Moscow have actually deepened.

Trade with Russia has increased significantly since the war began, with 2022 and 2023 being record years for Russia-Kazakhstan economic cooperation. Moreover, Russia’s influence extends to strategic sectors, including energy. It controls Kazakhstan’s main export route for oil and now owns 25% of Kazakhstan’s uranium production.

This economic interdependence, coupled with lingering security ties and Tokayev’s political debt to Putin following the 2022 CSTO intervention, has limited Kazakhstan’s ability to distance itself from Russia. For every diplomatic gesture towards the West, there seems to be a corresponding move to reassure Moscow of continued alignment.

In this context, opposition figures like Sadykov have found it increasingly difficult to operate within Kazakhstan. The persistent climate of repression, combined with the country’s growing ties to Russia, has pushed many dissidents to seek safety abroad, particularly in countries like Ukraine. However, as Sadykov’s case demonstrates, even in exile, Kazakh opposition figures continue to face risks, highlighting the long reach of authoritarian regimes and the ongoing struggle for political freedom in Kazakhstan.

Other political emigres assassinated in Ukraine

The assassination of Aidos Sadykov is part of a disturbing pattern of violence against political exiles and critics of authoritarian regimes in Ukraine.

In March 2017, Denis Voronenkov, a former Russian MP who had fled to Ukraine and become a vocal critic of Vladimir Putin, was shot dead in broad daylight in central Kyiv. Voronenkov was a key witness in the treason case against Ukraine’s ex-President Yanukovych and had provided testimony about Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine. His murder was described by Ukrainian officials as an “act of state terrorism by Russia.”

Another high-profile case occurred in October 2017, when Amina Okuyeva, a Ukrainian veteran of Chechen origin, was killed in an ambush near Kyiv.

Okuyeva, who had fought against Russian-backed forces in eastern Ukraine, was a prominent figure in the Chechen diaspora and a vocal critic of Ramzan Kadyrov, the Kremlin-backed leader of Chechnya. Her assassination, which followed an earlier failed attempt on her life, was seen as part of a broader campaign of violence against Chechen dissidents abroad.