From Soviet flags to TikTok stars: How Russia poisons Italy across generations

Nearly 30 years after the Soviet collapse, its symbols and distorted history mysteriously resurface in Italy - from textbooks to protests - as Russian propaganda and Kremlin-sponsored influencers sway Italian youth on social media.

Italy remains a pivotal target for Russian propaganda seeking to exploit past ties, though stances have shifted since the Ukraine full-scale invasion. Key aspects include:

- Like elsewhere in Europe, the Kremlin draws vocal support in Italy only from fringe far-right and far-left parties now. However, the right-wing Brothers of Italy party leading the governing coalition has strongly backed Ukraine.

- Due to historical reasons, Italian regions have a strong identity. Russia takes advantage of this by effectively spreading its propaganda among regional officials.

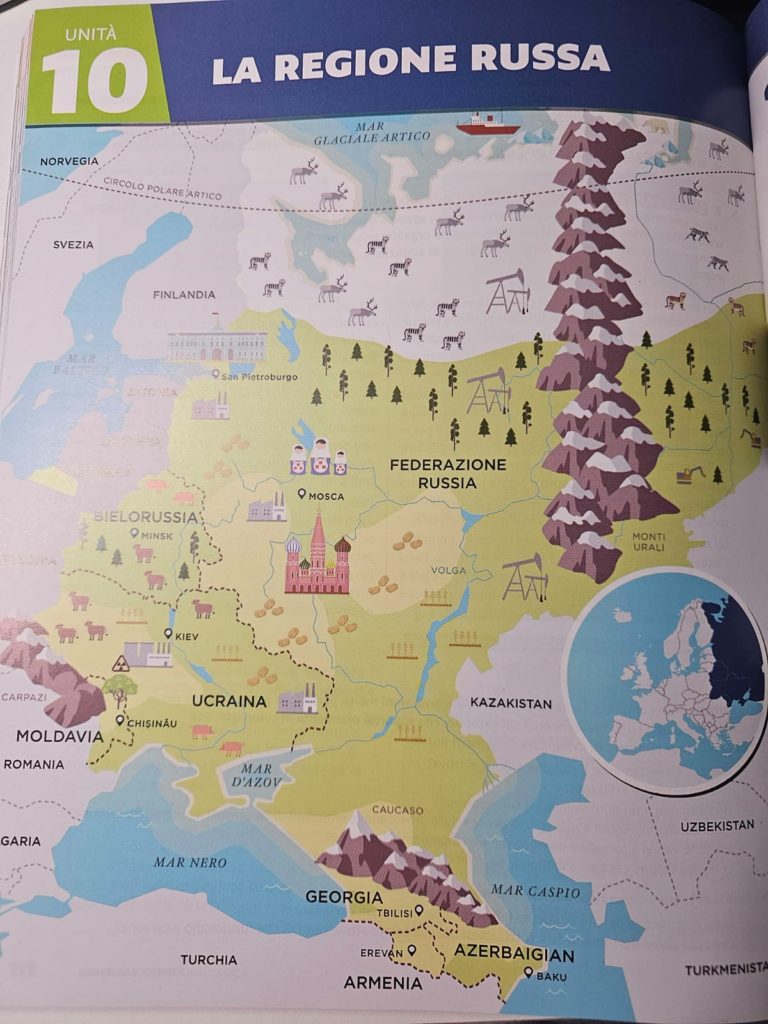

- Russian propaganda has reached Italian school textbooks, some of which, for example, attribute illegally annexed Crimea to Russia.

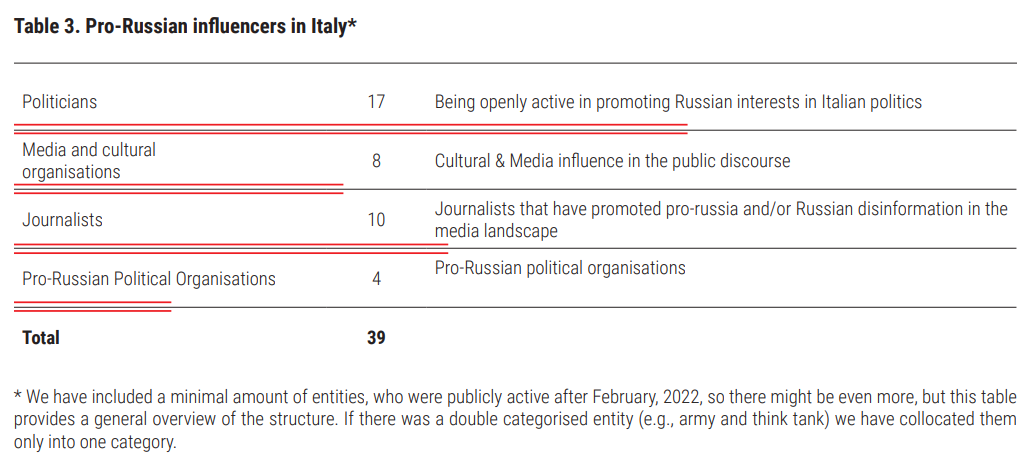

A new report “Revealing Russian Influence in Europe” by the Institute of Innovative Governance identified 39 active pro-Kremlin voices in Italy. By analyzing publicly available but dispersed information, the research maps Russia’s network of influencers embedded in media outlets, digital platforms, political parties, business groups, and lobbying organizations.

Thanks to this report, Euromaidan Press can spotlight key examples of Russian influence in Italy, showcasing the various tactics employed to manipulate European politics and societies. Raising public awareness of these campaigns aims to foster greater resilience.

In total, the report has identified 360 pro-Russian lobbyists active in Germany, France, Italy and Ukraine. Their common goals are undermining sanctions on Russia and weakening support for Kyiv.

For specifics on the web of Russian influence uncovered in Germany and France, see Euromaidan Press’ past coverage here and here.

Italy’s dance with Russia from Berlusconi to Meloni

Silvio Berlusconi, the influential former Italian prime minister whose political career spanned over two decades, forged extensive ties with Russia during his time in power, including a personal relationship with Putin. The 2002 NATO-Russia summit hosted by Berlusconi at Italy’s Pratica Di Mare air base, with Putin attending, marked formal alignment between Rome and Moscow – known as the enduring “Spirit of Pratica Di Mare” proclaimed by Italian right-wing factions.

According to researcher Andrea Castagna, co-author of the report “Revealing Russian Influence in Europe,” support for Ukraine has never been mainstream in Italian politics.

“Only a very narrow segment of the Italian political spectrum is pro-Ukrainian, maybe someone on the center-left or center-right. But historically, the Italian far-right, now part of the governing coalition, and far-left are very pro-Russian,” Castagna told Euromaidan Press.

Italian leaders across the spectrum who came after Berlusconi like Matteo Salvini, Giuseppe Conte and current PM Giorgia Meloni have also asserted special Russia connections.

Before its Ukraine invasion, Russia cultivated regional influence networks in Italy, exploiting strong local identities. Moscow backed groups like the Lombardy Russia Association, Liguria Russian Association and Veneto Russian Association to sway right-wing politics. They helped advance Moscow’s aims – from pushing policies recognizing occupied Crimea as Russian to arranging official regional visits there.

After February 2022, such overt ties brought stigma, but pro-Kremlin actors are adapting.

“Since the new year, they have a new propaganda approach – hosting film screenings and cultural events without openly using Russian symbols,” said Castagna.

For the first two years of full-scale war, that was taboo. Now pro-Russian Italian organizations promote propaganda movies about places like Russian-occupied Mariupol in coordinated campaigns, engaging the cultural sphere while keeping some distance from politics. This indirect, normalized technique spreads narratives favoring Russia.

Italian school textbooks are another conduit for Russian propaganda, the analyst explains. Some directly transmit Kremlin narratives, portraying Ukraine as part of a “Russian region” and calling Kyiv its oldest city. This poisons Italian public discourse.

“Textbooks present Ukraine and Russia as one great Russian region. Or they show maps with Crimea as part of Russia. There is a lot of misinformation on Ukraine, like claims there was a ‘civil war’ there,” said Castagna.

Economic ties rooted in energy bind Italy and Russia. Their governments fostered partnerships across sectors like manufacturing and agriculture, with Italy relying on Russia for 40% of annual energy imports pre-2022 when over 400 Italian businesses operated in the country. Overall export dependence was just 1.5%, but corporations created enduring links.

These compound reasons why sympathy for Moscow persists – the legacy of Italy’s influential pro-Soviet Communist Party anchoring networks across media, academia and industry figures who routinely tout Russian connections unchecked. With politicians emphasizing special relationships, public discourse stays vulnerable to Kremlin manipulation.

Italy’s pro-Russia political landscape

Fratelli d’Italia, also known as Brothers of Italy, has long advocated pro-Kremlin views locally and nationally. Its leader, current PM Giorgia Meloni, once expressed pro-Russian stances and skepticism on arming Ukraine but shifted since taking office.

Still, “Whenever Ukraine support is discussed, we have critical voices from ministries and parliament urging compromise with Russia,” Castagna says.

For example, Economic Development Minister Adolfo Urso, married to a Ukrainian refugee from Luhansk, was Italy’s first minister visiting wartime Ukraine.

“Yet Urso sometimes has very strange positions – in theory, he is very pro-Ukrainian but not everyone in his party is,” Castagna notes.

The right-wing Lega party and its leaders promote pro-Kremlin messaging in Italy. Party head Matteo Salvini has urged lifting Russia sanctions and strengthening ties, as have senior Lega figures like former MEP Mario Borghezio, ex-undersecretary Stefania Pucciarelli, and current Chamber speaker Lorenzo Fontana.

“Lega likely still has a formal agreement with Putin’s United Russia party. They recently faced criticism for refusing to condemn Navalny’s killing,” explained Castagna. “While critical of Ukraine, Lega tries to avoid the topic because it is sensitive. But they still have all these Russian links.”

On the populist left, the Five Star Movement has propagated pro-Russian positions as a major Italian political party. Former Five Star Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte stresses maintaining dialogue with Russia on defense, economics, and conflict resolution.

“The war shocked Conte as he could no longer openly back Russia. Yet after a few months, he adopted a ‘pro-peace’ stance favoring Ukraine ceding occupied territories to Russia to ‘find compromise.’ Conte consistently votes against Italian weapons shipments to Ukraine,” the analyst said.

Senior Five Star figures like MP Alessandro Di Battista and co-founder Beppe Grillo spread Russian disinformation labeling Ukraine a “US puppet” and legitimizing Crimea annexation.

The Five Star Movement frequently spreads conspiracies and disinformation through online platforms like TzeTze, La Cosa, and La Fucina. These are operated by Casaleggio Associati, a firm founded by one of the party’s founders, Gianroberto Casaleggio, and now run by his son.

While enabling Five Star fundraising and messaging, these sites also actively push content from Kremlin propaganda outlet Sputnik to disseminate pro-Russian narratives within Italy.

“The far left is also very pro-Russian, even more vocal and dangerous since they try to politicize Italian support for Ukraine,” stated Castagna.

The spread of pro-Kremlin views in Italian media

For years, Russian propagandists influencing Italian media narratives – on migration, Ukraine, NATO etc – have drawn concern. State broadcaster RAI enables personalities known for airing unchecked pro-Kremlin views, shaping public attitudes.

One such figure is Marc Innaro, a veteran correspondent for Italian state broadcaster RAI TV with extensive experience as a journalist in Moscow. He frequently appears on TV as an expert on Eastern Europe and promotes anti-Ukrainian and pro-Kremlin biases, suggesting Russia invaded Ukraine because of NATO expansion.

“Now the RAI Cairo bureau chief covering the Middle East, Innaro retains Russian contacts. The FSB likely has compromising material on him – he is a Russian asset,” said analyst Andrea Castagna.

Sergio Romano, 94, is a Cold War-era Italian ambassador to Moscow, writer and historian, now a prominent columnist at the newspaper Corriere della Sera, the major Italian media. He amplifies pro-Kremlin takes on issues like the 2014 Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine. In 2023, Romano said that Ukraine would have to cede occupied territories to Russia.

Gianfranco Pagliarulo is an Italian journalist and politician, serving as head of the National Association of Italian Partisans – an influential civil society group. Pagliarulo has called on the Italian government to “distance itself” from the war in Ukraine and cease military support for Kyiv.

“Closely tied to the Five Star Movement, the ‘pro-peace’ Partisans eschew pro-Putin rallies but march with Soviet flags, as the USSR fought fascism. They propagate narratives about Ukrainian “Nazism”. Though many question their relevance, they hold influence and receive state funding,” analyst Andrea Castagna explained.

Alessandro Orsini, being sociologist and terrorism scholar, serves as an associate professor at Rome’s LUISS University. He is a frequent talk show guest who is openly spreading Russian lies and blaming NATO for Putin’s Ukraine invasion. He also said that Putin can take Kyiv “in the shortest possible time,” but simply does not want it.

Vittorio Nicola Rangeloni operates as a pro-Russian war correspondent and fighter in occupied Donbas. Since 2015, his Italian YouTube channel has interviewed separatists and propagated Kremlin narratives. Post-2022 invasion, Rangeloni publishes likely coerced interviews with imprisoned Ukrainian military personnel.

Similarly, Andrea Lucidi began reporting from Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine in 2022 while sporting the invasion’s “Z” symbol. Parroting Kremlin talking points, Lucidi calls Ukraine a “Nazi regime,” denies the Bucha massacre, and spins Mariupol destruction as rebuilding efforts.

“Rangeloni’s neo-fascist ties make the media avoid him. Lucidi appears more credible without clear far-right links, earning greater media invites despite echoing Russian talking points,” analyst Andrea Castagna explained.

Small Russian diaspora enables visible Kremlin mouthpieces

Unlike Germany, Italy hosts a smaller, less influential Russian diaspora. Wealthy Russian oligarchs in Italy, like those residing in Sardinia, tend to maintain low profiles.

However, the diaspora community still enables some visible pro-Russia advocates such as Irina Osipova. As the daughter of a Russian diplomat in Italy, Osipova fiercely opposed Ukraine while organizing events and campaigning politically until around 2018. She then disappeared for years amid the invasion of Ukraine.

Recently the Italian media reported that Osipova secured employment in the Italian Senate administration with access to sensitive documents and information.

Yet according to analyst Andrea Castagna, “The Senate conducted no security clearances or double checks given her Italian nationality and internal competition success.”

Italy’s young parrot Kremlin views amid new propaganda surge

Several common narratives in Italy seek to sway public opinion towards Kremlin interests:

- Italy’s NATO and EU memberships undermine sovereignty, with policies overly influenced by the US;

- Italy shares profound cultural, economic and political bonds with Russia; not maintaining this special relationship is against Italian interests;

- Russia feels victimized by NATO enlarging eastward after the Cold War; Italy should reduce perceptions of provocation against Moscow.

According to analyst Andrea Castagna, after two quiet years, vocal Russia supporters have re-emerged touting Russian power and “winning” in Ukraine, ending US dominance for a better multipolar world. This spreads rapidly via traditional and social media, influencing younger generations.

Some propagators likely receive payment, but others genuinely believe the narratives, says Castagna. Recently, young Italians studying in Moscow broadcast daily life there, ignoring the war – perhaps indicating ideological commitment to Russia.

“There was a case last week on a young Italian student who was allowed to ask Putin a question on what he thinks about Italy. And suddenly this was all Italian channels because, wow, this young girl is so brave,” details Castagna.

Another such student is Amedeo Avondet, 23, from Turin University, who organized pro-Russian rallies urging attendees to demand Italian authorities halt aid to Ukraine. He claimed Italy must support Russia and lift sanctions. Avondet echoes Russian propaganda calling Ukraine “Nazi” and frequently appears in Moscow and on Italian TV.

Blending narratives – praising Russia while slamming the EU, NATO, sanctions – makes messaging of these young people resonate. Arguing Italy should join BRICS and break from weak, damaged alliances, they insist Russia would never harm its “ally” Italy though Ukraine suffers.

Italy remains a crucial target for Russian propaganda and political influence. While views have shifted after Russia’s full-scale Ukraine invasion, past relations still hold significant sway.

Pro-Kremlin propagandists have penetrated Italian media, including state broadcaster RAI. Today, narratives echoing loyalty to Moscow’s military action appear mainly from extreme ideological fringes. Yet moderate parties have also failed to distance sufficiently.

Debates criticize aiding Ukraine, accuse the West of war profiteering, and highlight the mistreatment of Russians in Italy – forfeiting Ukrainian interests for vague “peace.” Leftist intelligentsia and peace groups align with Moscow.

As Russian propaganda masquerades as free speech, there is a growing concern that Russia will intensify its efforts to exploit Italian vulnerabilities. Analyst Andrea Castagna highlights civil society as crucial in combating Russian narratives, emphasizing the need for unity and action. He also underscores the importance of education.

“We must better educate Italian citizens, as many lack historical context. They don’t understand Ukraine’s history or the roots of this war. As a result, they don’t have the tools to recognize propaganda,” noted researcher.

Castagna argues the Italian state should invest more in schools and adult education, fund civil society groups, and promote critical thinking in universities to counter Russian influence.

Read more:

- Report: Western media underestimate Russian propaganda’s effectiveness

- Italy’s opera house staged Russian opera despite Ukrainian protests; von der Leyen and Meloni visit it – AP

- Three Ukrainian poets to spoil Westsplaining fest in Italy

- How Russian propaganda adapts to the war

- Russian propaganda TV threatens to invade West, carry out nuclear strike

- Euromaidan and the Donbas war in the Italian media