Government borrowing exceeds estimates as public sector spending jumps

Monthly borrowing figures will be closely watched over the coming months for clues about how much Labour will raise taxes in October's Budget.

New figures show that the government borrowed more than expected in July as spending on public services increased faster than tax receipts.

Government borrowing – the difference between public sector spending and income – totalled £3.1bn last month, according to figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

This was ahead of the £100m predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) back in March and the £1.5bn expected by economists. It was also the highest July figure since 2021.

“Revenue was up on last year, with income tax receipts in particular growing strongly,” Jessica Barnaby, deputy director for public sector finances at the ONS said.

“However, this was more than offset by a rise in central government spending where, despite a reduction in debt interest, the cost of public services and benefits continued to increase.”

The ONS noted that the increase in public sector spending was largely due to inflation, with the cost of inflation-linked benefits rising alongside higher pay for public sector workers.

The figure means that borrowing in the financial year so far has totalled £51.4bn, the fourth highest year-to-July figure since 1993.

That was £0.5bn less than the figure for the same four months last year, but £4.7bn more than forecast by the OBR.

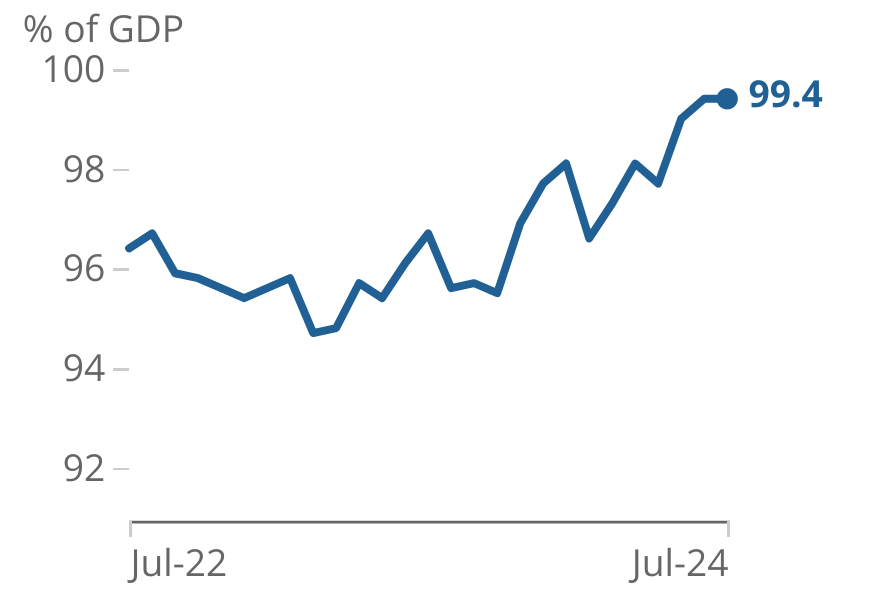

Public sector debt was estimated at 99.4 per cent of GDP, 3.8 percentage points higher than last year and the highest level since the early 1960s.

Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones said: “Today’s figures are yet more proof of the dire inheritance left to us by the previous government.”

Monthly borrowing figures will be closely watched over the coming months for clues about how much Labour will raise taxes in October’s Budget.

Denis Tatarkov, senior economist at KPMG UK, said that the higher than expected borrowing leaves “little headroom” ahead of the fiscal event.

He suggested the government’s buffer for meeting its key fiscal rule had narrowed from £9bn to £6bn.

The new government has inherited a very difficult fiscal position, with many public services in need of funding boosts while both the tax burden and national debt stand at their highest level for many decades.

During the election campaign, Labour repeatedly said that it had “no plans” to raise taxes beyond a fairly limited set of measures amounting to £7.3bn.

Economists were deeply sceptical of the party’s tax plans, and since taking office, Rachel Reeves has more or less confirmed that taxes will have to go up by more than was laid out in the manifesto.

Speaking on the News Agents podcast last month, Reeves said, “I think we will have to increase taxes in the Budget,” although she refused to comment on which taxes might rise.

Reeves has tried to pin the blame for the likely tax increases on the Conservatives by claiming the previous government left a £22bn blackhole in the public finances.

Jones said that the government was taking “tough decisions” to “fix the foundations” of the economy.