How Corporations Are Cashing in on Subsidized Low-Income Housing

Evette Gilard’s skin itched so badly that it woke her one night in early 2019. When she searched her apartment, she discovered a thick rind of black mold in the threshold of her bedroom closet, and another in her hallway. There had been an apartment fire upstairs months earlier, and Gilard supposed that water damage from the firefighters had caused the mold. She knew that her little subsidized one-bedroom in Antioch, California, was not exactly a luxury condo, but now she feared for her health.The next morning, Gilard told the property manager, who sent a maintenance man with a bleach-filled spray bottle. Knowing that bleach can spread mold on porous surfaces, she turned him away and appealed to the manager to give the problem more serious attention. Meanwhile, she was still living in the apartment, and her symptoms were getting worse. “My skin was changing, my voice was changing,” Gilard told me. “My hair was falling out.”After weeks of getting “the run-around” from the manager, Gilard finally called Antioch’s code enforcement office. In early March, a city employee appeared and issued the landlord a violation for the mold. Only then did the manager bring in contractors to cut open the walls and remediate. “I told them, I can’t live here,” she said. “It still had that scent there. All my clothes were ruined, bed sheets, everything was ruined because the smell was in my clothes and everywhere.” After she wrote a letter to the manager’s corporate office, the company put her up in a hotel, where Gilard stayed for a month. To this day, she has chronic skin problems. “The mold issue is an everyday thing,” she said. “My skin blisters, it bleeds. It took away some of my self-confidence.”Gilard had moved into the Casa Blanca Apartments in 2012. Her mother, sister, and sister’s five sons all lived in Antioch, a bedroom community of 117,000 people an hour’s drive east of San Francisco. When she signed her lease, the grounds of the complex—a Spanish Mission–style affair of beige stucco archways with red tiled roofing—were well landscaped and welcoming. Most importantly, the rent was low. At $745 a month, she could afford to live on her wages as a nursing assistant, even after she hurt her back on the job and went on disability insurance. She convinced her mother to move into Casa Blanca as well. But in 2016, a new landlord, Levy Affiliated Holdings—a real-estate investment firm with a portfolio of 41 properties and a market value of more than $500 million—bought the complex and redeveloped it using the low-income housing tax credit, the federal subsidy that finances most affordable apartments for poor and working people in the United States today. When I visited Antioch in September, Gilard and her neighbors said that their living conditions deteriorated when Levy Affiliated took over from the previous owner, the Affordable Housing Development Corporation. A succession of property managers has ranged from unresponsive to aggressive; some took months to fix simple problems like broken stoves. Residents suspect that one manager had a kickback arrangement with a local towing company, since many had their cars whisked away at great expense—sometimes in the time it took to unload groceries. Today, the security gates are inoperable, and strangers routinely enter the grounds to break into cars, use drugs, and dump trash. Everyone is fed up with the overflowing garbage bins, which invite possums and raccoons. Some tenants also accuse Levy of hardball tactics and questionable bookkeeping. Teresa Farias Lúa and Dulce Franco said that they once received three-day eviction notices when their young sons went swimming together in the complex pool, which has been cracked and off-limits for seven years. Franco, a restaurant worker, said that she also received an eviction notice because her diabetic mother, who lives with her, is not on the lease. “We cried,” Franco told me. “I said, ‘Where is she going to go?’” Management never followed through; it felt like an intimidation strategy. Management never followed through; it felt like an intimidation strategy. Risa Peoples, an in-home care provider, was assessed an outstanding balance of more than $15,000, a sum that she staunchly disputes. She is trying to resolve the issue through Legal Aid but is afraid that she will be forced to leave. “I’m stressed out. I can’t eat because of this,” Peoples said. “They could take me to court and give me an eviction.”These indignities reached a breaking point in May 2022 when roughly 150 tenants at Casa Blanca and Delta Pines, a nearby property also owned by Levy Affiliated, received shocking rent-increase notices. In two months, Gilard’s notice read, her rent would rise from $1,125 to $1,542 per month, a 37 percent increase that would make life all but unworkable. “You just told me my rent is going up $400, but I’m living in low-income housing,” Gilard said. “How is that possible?”Levy Affiliated is just one of many thousands of companies that have

Evette Gilard’s skin itched so badly that it woke her one night in early 2019. When she searched her apartment, she discovered a thick rind of black mold in the threshold of her bedroom closet, and another in her hallway. There had been an apartment fire upstairs months earlier, and Gilard supposed that water damage from the firefighters had caused the mold. She knew that her little subsidized one-bedroom in Antioch, California, was not exactly a luxury condo, but now she feared for her health.

The next morning, Gilard told the property manager, who sent a maintenance man with a bleach-filled spray bottle. Knowing that bleach can spread mold on porous surfaces, she turned him away and appealed to the manager to give the problem more serious attention. Meanwhile, she was still living in the apartment, and her symptoms were getting worse. “My skin was changing, my voice was changing,” Gilard told me. “My hair was falling out.”

After weeks of getting “the run-around” from the manager, Gilard finally called Antioch’s code enforcement office. In early March, a city employee appeared and issued the landlord a violation for the mold. Only then did the manager bring in contractors to cut open the walls and remediate. “I told them, I can’t live here,” she said. “It still had that scent there. All my clothes were ruined, bed sheets, everything was ruined because the smell was in my clothes and everywhere.” After she wrote a letter to the manager’s corporate office, the company put her up in a hotel, where Gilard stayed for a month. To this day, she has chronic skin problems. “The mold issue is an everyday thing,” she said. “My skin blisters, it bleeds. It took away some of my self-confidence.”

Gilard had moved into the Casa Blanca Apartments in 2012. Her mother, sister, and sister’s five sons all lived in Antioch, a bedroom community of 117,000 people an hour’s drive east of San Francisco. When she signed her lease, the grounds of the complex—a Spanish Mission–style affair of beige stucco archways with red tiled roofing—were well landscaped and welcoming. Most importantly, the rent was low. At $745 a month, she could afford to live on her wages as a nursing assistant, even after she hurt her back on the job and went on disability insurance. She convinced her mother to move into Casa Blanca as well.

But in 2016, a new landlord, Levy Affiliated Holdings—a real-estate investment firm with a portfolio of 41 properties and a market value of more than $500 million—bought the complex and redeveloped it using the low-income housing tax credit, the federal subsidy that finances most affordable apartments for poor and working people in the United States today. When I visited Antioch in September, Gilard and her neighbors said that their living conditions deteriorated when Levy Affiliated took over from the previous owner, the Affordable Housing Development Corporation. A succession of property managers has ranged from unresponsive to aggressive; some took months to fix simple problems like broken stoves. Residents suspect that one manager had a kickback arrangement with a local towing company, since many had their cars whisked away at great expense—sometimes in the time it took to unload groceries. Today, the security gates are inoperable, and strangers routinely enter the grounds to break into cars, use drugs, and dump trash. Everyone is fed up with the overflowing garbage bins, which invite possums and raccoons.

Some tenants also accuse Levy of hardball tactics and questionable bookkeeping. Teresa Farias Lúa and Dulce Franco said that they once received three-day eviction notices when their young sons went swimming together in the complex pool, which has been cracked and off-limits for seven years. Franco, a restaurant worker, said that she also received an eviction notice because her diabetic mother, who lives with her, is not on the lease. “We cried,” Franco told me. “I said, ‘Where is she going to go?’” Management never followed through; it felt like an intimidation strategy. Management never followed through; it felt like an intimidation strategy. Risa Peoples, an in-home care provider, was assessed an outstanding balance of more than $15,000, a sum that she staunchly disputes. She is trying to resolve the issue through Legal Aid but is afraid that she will be forced to leave. “I’m stressed out. I can’t eat because of this,” Peoples said. “They could take me to court and give me an eviction.”

These indignities reached a breaking point in May 2022 when roughly 150 tenants at Casa Blanca and Delta Pines, a nearby property also owned by Levy Affiliated, received shocking rent-increase notices. In two months, Gilard’s notice read, her rent would rise from $1,125 to $1,542 per month, a 37 percent increase that would make life all but unworkable. “You just told me my rent is going up $400, but I’m living in low-income housing,” Gilard said. “How is that possible?”

Levy Affiliated is just one of many thousands of companies that have sprung up over the last four decades to maximize profits through subsidized rentals, especially by taking advantage of public money through the low-income housing tax credit, or LIHTC (pronounced “lie-tech” by industry insiders). Created in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the LIHTC was meant to improve on the government-run public housing projects of a previous era—by largely outsourcing affordable rentals to private enterprise.

The vast majority of LIHTC housing is in the hands of large, regional corporations. And in recent years, private-equity titans like the Blackstone Group and Starwood Capital have begun snatching up affordable units as they increase their share of the rental housing market. These companies routinely inflict misery on poor tenants, who are afforded weak protections by the LIHTC program. Generally speaking, corporate landlords are more likely to raise rents and fees, create poor health conditions, and evict tenants than other types of owners. They form limited partnerships that obscure ownership, making them nearly impossible for tenants to hold accountable. In LIHTC housing specifically, these owners increase their profit margins by cutting basic services, neglecting maintenance of problems like mold and pests, and jacking up rents. Some are finding loopholes to terminate affordability requirements, leaving tenants to hash out life on the open market.

Despite these problems, government leaders from both political parties continue to back the LIHTC program as the country’s leading approach for creating low-cost rentals, enabling a beast of profiteering while doing little to tame its excesses. And at a moment when working people are struggling to make rent, Vice President Kamala Harris, as part of her campaign’s housing plan, wants to double down on this program that too often enriches landlords while making life hell for renters.

Affordable housing used to be the domain of the federal government. In the New Deal era, policymakers began funding local authorities to build and manage public housing directly. The Housing Act of 1937 was the result of a bargain with the real estate lobby, which guaranteed that public housing would be produced to a low and alienating physical standard. Still, for decades, these apartments served poor and working people in cities across the country.

In the postwar period, however, federal policymakers got busy subsidizing white families to buy homes in the suburbs, a project that excluded Black and other non-white households. By the 1970s, the political mood had lurched rightward. “The whole idea that public housing was based on—that government can do good things and create large programs of assistance where the market has failed—was set aside,” said Edward Goetz, a professor of urban planning at the University of Minnesota and the author of New Deal Ruins. “That meant moving away from direct public investment and toward incentivizing the private sector to build.” Both Democrats and Republicans agreed on slashing funding for public housing, now largely the province of a Black urban poor. The tall brick boxes that once provided stable homes deteriorated and came to represent crime and extreme poverty. Lacking federal funding, local officials began using these problems as justification to demolish the buildings. Today, America loses as many as 15,000 units of public housing each year.

What has arisen in its place is a byzantine web of government programs designed to shift rental assistance to the private market. Chief among them is the LIHTC program, which since its inception has created some 3.65 million affordable units—and a food chain of ravenous middlemen has cropped up to bite off chunks of the now $13.5 billion in tax breaks the program hands out each year.

Under the LIHTC program, the Internal Revenue Service allocates tax credits to state and local housing agencies, which in turn award those credits competitively to developers wishing to build or rehabilitate affordable housing. Developers, however, rarely use the tax credits themselves. Instead, they sell them to investors at a discount—or else to “syndicators,” companies that charge developers a fee to find investors for them. These investors, usually large national banks, get tax breaks for ten years and a 99 percent ownership share; the developers get the up-front capital they need for construction. In effect, developers are building apartments using public money, which, in theory, allows them to keep rents lower than market rate. The program requires that rents remain affordable for at least 30 years—though what counts as affordable often still leaves tenants struggling to make ends meet.

For all these reasons, the LIHTC program is highly inefficient, more so than other forms of housing subsidy. “Millions of dollars get siphoned off to legal fees and financing fees,” Goetz said. “For every dollar that it costs the federal government, a significant portion of that does not go to assisting families.”

LIHTC housing is all around you, mixed into market-rate high-rises and squatting between other low-slung apartment complexes. Antioch is a classic location for it. An affluent white Bay Area suburb in the mid-century, the city has in recent decades undergone a reversal, becoming majority Black and Latino as its white population moves back to major cities like San Francisco. Today, the city is 25 percent white, 20 percent Black, 35 percent Latino, and 14 percent Asian, according to Census data. There are pockets of severe poverty and homelessness in Antioch, but they’re surrounded by wealthier communities, both within the city and the broader metro area. Developers like to build LIHTC apartments in highly unequal places like this because the rules of the program—which sets rents based on income figures for the entire metro area—allow them to rent units in low-income neighborhoods for close to, and sometimes even more than, local market rates.

Most LIHTC developers—as many as 80 percent, according to data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development—are for-profit companies, while some are mission-driven nonprofits interested in maintaining housing for the poor and keeping rents low. But even the latter can assume for-profit characteristics in today’s overheated real estate market, such as high CEO and board pay and partnerships with profiteers. “In a lot of nonprofits where tenants in the past have had good experiences, we’re seeing the mission-driven aspect of them kind of erode,” explained Chris Schildt, director of housing justice for Urban Habitat, who co-authored a recent report on affordable housing in California. “They’re becoming more profit-seeking in their behavior.”

Casa Blanca is owned as a joint venture between Levy Affiliated and a nominal nonprofit called Central Valley Coalition for Affordable Housing, whose CEO takes an annual salary and benefits package exceeding half a million dollars. The state granted Levy a tax credit of nearly $540,000 per year for ten years, which the firm then sold to the syndicator WNC & Associates for a total of $5.5 million, according to public records. Levy also collected a $1.8 million “developer fee” for performing renovations to Casa Blanca. As for rent, when proposing the rehab of the property the landlord projected a net income of nearly $13.5 million over the first 15 years of the project. But rents can always be increased, and costs can be cut. (The company did not respond to requests for comment.)

This whole feeding frenzy is supposed to yield the public benefit of affordable apartments. In truth, the LIHTC program was always designed for higher-earning families than public housing or Section 8 vouchers, which cap rents at 30 percent of household income. The LIHTC program mainly serves households earning 60 percent or less of a metro area’s median income, setting rents at around 30 percent of that figure. Thus, the allowable monthly LIHTC rents in Antioch are $1,752 for a one-bedroom and $2,103 for a two-bedroom, in part because income and costs in the greater metro area are relatively high. The program permits mid-lease rent hikes, and until 2024 it placed no limits on the amount landlords could increase rent. States like California, despite laws enshrining tenant protections and rent caps, often exclude affordable housing tenants.

Despite these higher income targets, the reality is that a lot of poor people live in LIHTC housing because they have few options. Nationwide, more than half of the program’s households qualify as extremely low-income, earning below 30 percent of the median income for the area. As many as half may require additional forms of rental assistance, like Section 8 vouchers. And they struggle: Two out of five LIHTC tenants are rent burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent, and one out of eight is severely rent burdened, spending more than half.

“It is a program that is affordable to people who are moderate-income, and that means fundamentally that it’s excluding or not providing the necessary support for people who are at the very low-income end of the range,” said Yonah Freemark, a housing researcher at the Urban Institute. “We have ended up with this situation where we have major housing problems for that group.”

Extremely low-income tenants are, of course, precisely the group that public housing projects historically served, and the government’s retreat from such projects has left these vulnerable people scrambling. That’s one reason that some advocates and politicians on the left today are fighting to revive it.

California is hardly the only state where corporate owners use the LIHTC program to maximize profits while their tenants suffer. Across the country, federal and state oversight bodies have allowed poor living conditions to fester. How common are they? Official records make it difficult to tell. Yet in any city you care to name, tenants and organizers can reel off examples of intolerable problems.

In 2023, Tyrone Stevens moved into the senior living complex of Wheatley Courts, a 412-unit property in San Antonio, Texas, that was redeveloped in part using the LIHTC program. Stevens was forced to retire from his career as a nursing assistant when his lungs were badly damaged by Covid-19, and Wheatley Courts promised an affordable, disability-friendly place to live. But when summer came around, the central air conditioning malfunctioned during weeks of 100-degree heat. His landlord, national for-profit developer McCormack Baron Salazar, failed to repair it, despite tenants’ repeated appeals. That winter, the heating system failed, driving some of Stevens’s neighbors to sleep with their stoves on to stay warm. Eventually, McCormack Baron Salazar responded to residents’ demands by shipping space heaters to the complex, but Stevens’s heater didn’t work. Summer of 2024 brought a new round of broken air conditioning during blistering heat. “It’s very hard on us senior citizens who are disabled,” Stevens said. “They keep saying they’re fixing it, but they ain’t doing nothing but patching it up.”

McCormack Baron Salazar worked with the city’s housing authority to redevelop Wheatley Courts, previously an infamous public housing project, under an Obama-era initiative designed to encourage private investment in “opportunity neighborhoods.” Public records show that, in 2018, the landlord collected tax credit equity of more than $43 million, along with developer fees exceeding $6.3 million. The property’s complexes draw a net income of $583,000 annually. (In an email, a spokesperson for McCormack Baron Salazar claimed that the company faces financing challenges at Wheatley Courts due to a pandemic-era eviction moratorium and rising insurance costs. The company noted that its property manager has contracted with an HVAC repair firm and provided tenants with “alternative temporary cooling or heating units or alternative accommodations where needed.”)

When developers receive tax credits, state housing agencies are charged with monitoring their properties for compliance with rent, income, and habitability standards. In theory, agencies report violations to the IRS, which can claw back tax credits during the first 15 years. (After that, enforcement is wholly up to the state.) In practice, though, agencies are only required to inspect properties every three years, and only for 20 percent of units. Often, they end up doing “desk audits,” which don’t require in-person visits. Plenty of violations are found but never reported to the IRS, and plenty are never detected at all, according to reporting from Shelterforce. For the public, it’s all but impossible to learn which developers are bad actors.

Problems can occur when HUD brings on for-profit developers to rehab old publicly owned projects. At Memphis Towers, in Tennessee, HUD sold off a share of a Section 8 complex to the Millennia Companies, which used tax credits to redevelop the property. By 2024, after years of resident complaints about broken elevators, hot water problems, and mold, HUD forced Millennia to sell to another LIHTC developer. But problems have persisted under the new ownership. At Sandpiper Cove, a Section 8 property in Galveston, Texas, tenants also suffered under a botched LIHTC redevelopment scheme by Millennia. Many were living in homes with ceilings caving in, and mold was causing tenants severe illness before HUD made the company sell. “Part of the problem is that the owners are almost always national banks,” explained Michael Daniel, a civil rights attorney for Lone Star Legal Aid, which represented the Millennia tenants. “The developer may have just gotten their fee and gone.”

All kinds of federally subsidized properties have problems with accountability. But the LIHTC program’s oversight design—which starts with state agencies that lack enforcement power and ends with an IRS that has no housing expertise—makes it inherently vulnerable to abuse, said Amee Chew, a housing researcher at the nonprofit Popular Democracy. Mostly, the program relies on the affordable housing industry to police itself. The idea is that syndicators and investors are loath to lose their tax credits, developers to lose their reputations, and therefore will follow the rules. In effect, the LIHTC program takes the government bureaucracy of HUD and outsources it to the private sector. But in countless cases, these incentives fall far short of protecting against health and safety violations. “It’s a tax credit program,” Chew said. “It wasn’t set up, necessarily, with tenants’ interests in mind first.”

In the absence of strong accountability mechanisms, it’s largely up to tenants to organize and fight for their own interests. Some are doing just that.

Teresa Farias Lúa was never one for protests, but her experience at Casa Blanca, where she has lived with her husband since 2011, changed that. For weeks when Levy Affiliated rehabbed the complex in 2017, she recalled, her family was kicked out of their apartment early in the morning and corralled in the manager’s office while her husband went to work. Her three young children went back to sleep on the manager’s carpets as contractors cheaply replaced their unit’s flooring and appliances. “It was painful to see that scene of my kids on the floor,” Farias Lúa said. “It was a lot of suffering.”

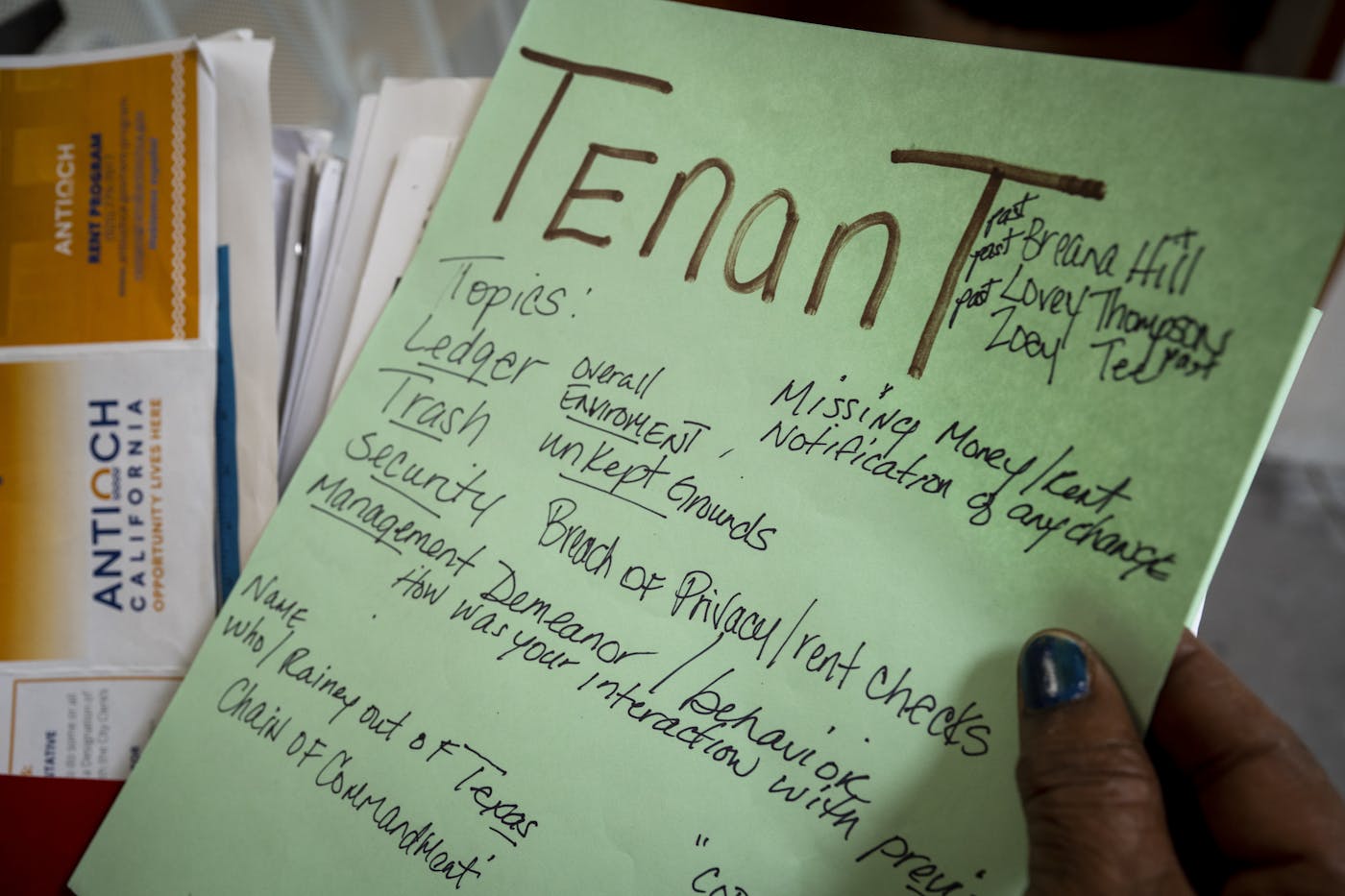

Like her neighbors, Farias Lúa received notice of a steep rent increase in May 2022, from $1,181 per month to $1,542. At the new rate, she and her family would have to move. Where could they afford to go? Farias Lúa remembered that Rising Juntos, a local Spanish-speaking advocacy group, had been coming around Casa Blanca to ask residents about conditions. So she called a Rising Juntos organizer who had left a pamphlet at her apartment. The organizer told her to start talking to her neighbors. At the same time, members of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment were talking to residents of Delta Pines, the Levy-owned complex a few miles across Antioch. That summer, the groups began holding tenant meetings, talking to the local media, and rallying in front of city hall. ACCE sent a dispatch of tenants down to Santa Monica to protest at the landlord’s offices.

Facing this onslaught, Levy capitulated, withdrawing the rent hikes and investigating a manager who had caused particular misery at Delta Pines. For Farias Lúa and her neighbors, the victory was galvanizing. Now they wanted city laws on the books to protect them, so they began fighting for a local rent stabilization ordinance. In August 2022, more than 100 low-income tenants took their fight to City Hall, where they spent hours in council chambers telling stories of rent hikes, maintenance problems, and harassment by management. Most moving to Farias Lúa was seeing her oldest son speak directly to the mayor, pleading with him to keep their family off the street. At the end of the night, the City Council narrowly approved the ordinance, which limits rent increases to 3 percent annually. Importantly, it protects LIHTC properties, where state law fails to.

“It felt like a weight was lifted off my shoulders,” Farias Lúa said, sitting at her kitchen table flanked by two neighbors, all wearing green Rising Juntos shirts. “The countless hours of work were worth it. I did things that I never imagined myself doing, like giving interviews to the press, speaking in front of the City Council.” Together, they have continued to win protections. In 2023, the city passed a law penalizing landlords for harassment and retaliation, and in 2024 it unanimously approved a “just cause eviction” ordinance limiting the ability of landlords to remove tenants from their homes.

Nationwide, LIHTC tenants have relied on such local organizing to win legal safeguards that are absent from federal and state law. “It’s just a first step to keeping tenants housed with dignity,” said Rhea Elina Laughlin, executive director of Rising Juntos. “Undoubtedly, our affordable housing system is broken. Models that sacrifice maintenance and upkeep to make ends meet do not work.”

Still, the LIHTC model is what we have. It currently produces a huge amount of low-cost housing at a moment when low-income renters desperately need it. Reformers want to make the program bigger and better, with stronger regulations. At the federal level, the program is clearly top of mind. In April 2024, the Biden administration implemented a 10 percent cap on annual rent increases for LIHTC properties. Soon after that, Kamala Harris announced a sweeping plan to reduce barriers to building new homes, which includes a provision to smooth the production of LIHTC apartments. The Harris campaign’s housing policy proposal also leans heavily on the idea of “unlocking” 1.2 million new rentals by expanding the program. Meanwhile, the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act, a bipartisan bill sponsored by Rep. Darin LaHood of Illinois and Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington among others, and likely to be reintroduced in 2025, would greatly expand funding for the LIHTC program, providing increased tax benefits for investors along with other incentives.

Yet neither Harris’s plan nor the upcoming bill addresses fundamental questions about keeping rents low and protecting tenants in LIHTC properties. Marcos Segura, a staff attorney at the National Housing Law Project, said that the bill, when reintroduced, should incorporate a rent formula based on tenants’ income instead of area median income. It should also add clearer “just cause eviction” protections, standardized lease provisions, and measures to increase transparency about ownership and habitability. “This is probably the last opportunity for the next ten or 15 years to fundamentally change the way the program is structured,” Segura said. “A lot of the issues, you’re not going to solve through administrative action by the Treasury Department, and you’re not going to solve on the state level. You need to change the tax credit statute.”

Many progressive experts would rather see the country wean itself off tax credit housing. Organizations like Popular Democracy call for plans that support social housing, including public housing and other community-controlled rental options that are deeply and permanently affordable—and that sidestep the private market. Sixteen million families currently need federal housing assistance but don’t receive it due to funding limits, Chew noted. “There’s no way around generous, direct, up-front public money in the form of grants and low-interest loans in order to make the housing work for those who need it most,” she said. “It’s for public goods, and that’s worth the cost, because housing is a basic need and a human right.”

Some lawmakers have begun to heed such calls. In September, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Sen. Tina Smith of Minnesota introduced the Homes Act, a plan to fund the creation of social housing. The bill would forge a new federal development authority to build as many as 1.25 million homes, to be owned by public entities and community organizations. It would also fund public housing and repeal the Faircloth Amendment, which blocks cities from building new public housing. In a New York Times essay announcing the bill, Ocasio-Cortez and Smith explicitly propose the bill’s provisions as a corrective to the LIHTC program: “The largest affordable housing incentive our government offers—the low-income housing tax credit—too often ends up in the hands of for-profit developers.”

Today, Gilard lives in a newer, mold-free apartment in Casa Blanca. In late 2019, her landlord agreed to relocate her to a renovated one-bedroom. She keeps it dark and cozy inside, and the walls are decorated with pictures of her sister, who died of cancer two years ago, along with inspirational phrases (“love yourself”). The stove doesn’t work well, and the flooring was installed with sharp edges exposed. But at her current rent of $1,198 per month, the apartment still fits her budget.

At tenant meetings and City Council sessions, Gilard is a passionate participant. She is encouraged by the passage of local tenant protections, and that the pressure campaign has spurred Levy Affiliated to make small improvements around the complex. “It shows you that if you stand up for your rights, things can change,” she said. Gilard continues to stand up. Since the state has not held Levy accountable, she and her neighbors recently petitioned the city to force the landlord to address persistent problems with trash and security on the property.

Still, Gilard feels stuck in her home. The conditions that she and her neighbors face depress her. “They treat us according to our income, like we’re peasants,” Gilard said. “These are people,” she added, referring to her fellow tenants, “who get up every morning and work hard for their money.”