How Lucy Sante Wrote a Revelatory Memoir

No genre tests the delicate trust between author and reader like memoir. It is unavoidably provocative, a case study of the fragile magic act that all creative writing entails: claiming authority to tell the truth and make the past hold still, continually raising the question of how its author-subject should have found time to undergo experiences worth reading about and then to juice and distill and rearrange them for us. What could sound more boring, after all, than the true history of a serious writer of prose—especially nonfiction of the burnished, richly detailed, heavily researched kind—given all the color and incident and conflict presumably foregone during hours and years squirreling at a desk, not to mention the long stretches of youthful bookish loneliness that must form such writers in the first place? No wonder memoir still so often follows the line indicated by Augustine’s Confessions, privileging the inner life, and hinging on an epiphanic moment through which its course is altered and reread.Twenty-six years ago, in her first memoir, The Factory of Facts, Lucy Sante pointedly disdained this approach. Investigating how a self is forged from the surrounding culture and history, that book opens with a delightful set of variations on the same life story: Each successive paragraph begins from the same point—the author’s birth in 1954 as the only child of working-class parents in Verviers, Belgium—but each version takes a fanciful hairpin turn. The author moves to a luxurious villa in the Belgian Congo right before independence; is starved, beaten, and relegated to a series of foster homes after dad is removed by the FBI; becomes a competitive cyclist; a boarding school arsonist; an international beach-bum hedonist; a secretary to the papal nuncio in El Salvador. The rest of the book treats Sante’s actual background with the playfulness, imaginative force, and ferocious close reading that have characterized her work from Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991) to Nineteen Reservoirs: On Their Creation and the Promise of Water for New York City (2022). The effect is an elegant tracing around the author’s interior, without delving too far in.It would seem that Sante has since tired of such formalized reticence. Her new book, I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition, entwines a sped-up, more or less chronological version of her life story with a markedly direct account of her coming to consciousness as a transgender woman at the age of 66. She undergoes the epiphany while using FaceApp: Applying a gender-swap filter to a selfie, she recognizes the woman in the new picture—a self undeniably hers. She starts to allow in thoughts and longings she had energetically repressed for some 60 years, confronting vaulted memories from childhood onward as she runs photographs from each era through the filter, feeling in every case the same jolt of recognition. There she is, only “how much more relaxed she looked”: “I was having a much better time as a girl in that parallel life.”The transfigured snapshots “managed to force open a door” in her subconscious, “one festooned with padlocks and wax seals and warning signs in nineteen languages.” The evasiveness of The Factory of Facts now appears glaring to her, the attempt “to absent myself from the story” a defensive move: She had told herself that rendering her own emotions would “reduce and standardize the narrative.” She had “thought this demurral was a measure of my seriousness.”This brief self-reassessment exemplifies the subtle tragicomedy Sante draws from one of the new book’s central questions: how she can have dedicated the better part of a lifetime to analyzing the culture around her—its prehistories, its unarchived detritus, its collective mythologies—rescuing so much of what she loved from oblivion or nostalgic distortion, without ever uncovering this fundamental truth about herself. It’s not just the sheer irony of a writer having congratulated herself on the feat of repression that produced an entire memoir without revealing anything personal. Sante is also offering a casually self-lacerating sketch of that familiar persona, the cooler-than-thou male aesthete-intellectual who cares for large social forces, smaller cultural ephemera, and not much between. Alongside Sante’s experiences navigating the new social and emotional territory that comes with acknowledging her gender, I Heard Her Call My Name explores other kinds of transition, and transitional objects—it’s about taste, in art and music and crushes and books and clothes, and the ways it can build and sustain or obscure a self.Taste, as a mode of self-definition, rebellion, belonging, provides the thread for Sante’s biography as she recounts it here, from a sheltered but unsettled childhood between Belgium and New Jersey, to the New York of the ’70s and ’80s—working at the Strand and The New York Review of Books, drunkenly dancing to Billie Holiday records at Elizabeth Hardwick’s ap

No genre tests the delicate trust between author and reader like memoir. It is unavoidably provocative, a case study of the fragile magic act that all creative writing entails: claiming authority to tell the truth and make the past hold still, continually raising the question of how its author-subject should have found time to undergo experiences worth reading about and then to juice and distill and rearrange them for us. What could sound more boring, after all, than the true history of a serious writer of prose—especially nonfiction of the burnished, richly detailed, heavily researched kind—given all the color and incident and conflict presumably foregone during hours and years squirreling at a desk, not to mention the long stretches of youthful bookish loneliness that must form such writers in the first place? No wonder memoir still so often follows the line indicated by Augustine’s Confessions, privileging the inner life, and hinging on an epiphanic moment through which its course is altered and reread.

Twenty-six years ago, in her first memoir, The Factory of Facts, Lucy Sante pointedly disdained this approach. Investigating how a self is forged from the surrounding culture and history, that book opens with a delightful set of variations on the same life story: Each successive paragraph begins from the same point—the author’s birth in 1954 as the only child of working-class parents in Verviers, Belgium—but each version takes a fanciful hairpin turn. The author moves to a luxurious villa in the Belgian Congo right before independence; is starved, beaten, and relegated to a series of foster homes after dad is removed by the FBI; becomes a competitive cyclist; a boarding school arsonist; an international beach-bum hedonist; a secretary to the papal nuncio in El Salvador. The rest of the book treats Sante’s actual background with the playfulness, imaginative force, and ferocious close reading that have characterized her work from Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991) to Nineteen Reservoirs: On Their Creation and the Promise of Water for New York City (2022). The effect is an elegant tracing around the author’s interior, without delving too far in.

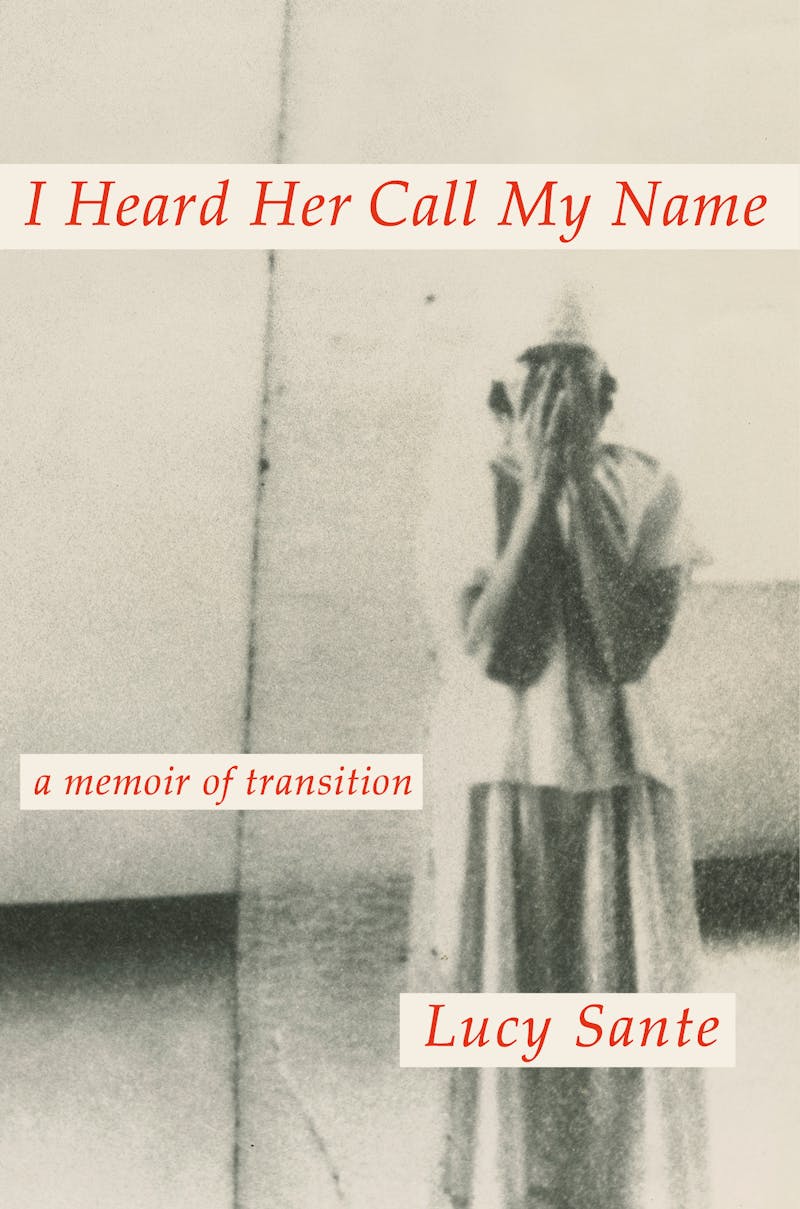

It would seem that Sante has since tired of such formalized reticence. Her new book, I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition, entwines a sped-up, more or less chronological version of her life story with a markedly direct account of her coming to consciousness as a transgender woman at the age of 66. She undergoes the epiphany while using FaceApp: Applying a gender-swap filter to a selfie, she recognizes the woman in the new picture—a self undeniably hers. She starts to allow in thoughts and longings she had energetically repressed for some 60 years, confronting vaulted memories from childhood onward as she runs photographs from each era through the filter, feeling in every case the same jolt of recognition. There she is, only “how much more relaxed she looked”: “I was having a much better time as a girl in that parallel life.”

The transfigured snapshots “managed to force open a door” in her subconscious, “one festooned with padlocks and wax seals and warning signs in nineteen languages.” The evasiveness of The Factory of Facts now appears glaring to her, the attempt “to absent myself from the story” a defensive move: She had told herself that rendering her own emotions would “reduce and standardize the narrative.” She had “thought this demurral was a measure of my seriousness.”

This brief self-reassessment exemplifies the subtle tragicomedy Sante draws from one of the new book’s central questions: how she can have dedicated the better part of a lifetime to analyzing the culture around her—its prehistories, its unarchived detritus, its collective mythologies—rescuing so much of what she loved from oblivion or nostalgic distortion, without ever uncovering this fundamental truth about herself. It’s not just the sheer irony of a writer having congratulated herself on the feat of repression that produced an entire memoir without revealing anything personal. Sante is also offering a casually self-lacerating sketch of that familiar persona, the cooler-than-thou male aesthete-intellectual who cares for large social forces, smaller cultural ephemera, and not much between. Alongside Sante’s experiences navigating the new social and emotional territory that comes with acknowledging her gender, I Heard Her Call My Name explores other kinds of transition, and transitional objects—it’s about taste, in art and music and crushes and books and clothes, and the ways it can build and sustain or obscure a self.

Taste, as a mode of self-definition, rebellion, belonging, provides the thread for Sante’s biography as she recounts it here, from a sheltered but unsettled childhood between Belgium and New Jersey, to the New York of the ’70s and ’80s—working at the Strand and The New York Review of Books, drunkenly dancing to Billie Holiday records at Elizabeth Hardwick’s apartment, reveling downtown at the Mudd Club and losing half the day to heroin or pills (though by the mid-’80s everyone was in recovery, serving seltzer-and-cranberry Transfusions at their gatherings), hanging out with Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, with Nan Goldin and Jim Jarmusch and Jean-Michel Basquiat—to making her name as a writer and retreating somewhat into family life upstate.

Though she seems to have felt alien everywhere she went, Sante established herself as an insider, always in the know. That male connoisseur character was a role she took such pains to develop and inhabit over the decades that now and then she overdid it—hence, she notes, being surprised and ashamed when a reviewer pointed out that Kill All Your Darlings, which collected 15 years’ worth of pieces on writers, artists, and musicians, omitted any serious treatment of a woman. While many women artists had been “of critical importance to me,” she writes, she’d avoided considering them in print because she “had unconsciously subscribed to the dick-matching ethos” in which “men’s work was serious, a life-or-death struggle to reach the top,” while women’s was “asterisked, italicized, special-categoried, exceptions made for, not entered in the main competition.”

You can even detect a hint of the same pose in a 2003 afterword to Low Life, in which, recalling her neighborhood of the late ’70s on Broadway and 101st, she tempered outsider kinship and solidarity with careful if self-deprecating detachment:

a rather eerie daily entertainment in the warmer months was provided by a group of middle-aged transvestites who would lean against parked cars in their minidresses and bouffants and issue forth perfect, obviously church-trained four-part doo-wop harmonies.… For them, as for the majority of the people on the street—including, so we liked to think, us—New York City was the only imaginable home, the only place that posted no outer limit on appearance and behavior.

It’s striking now how much inner confinement (that parenthetical “including, so we liked to think, us”) accompanied Sante’s seekings of those freer edges of culture.

Sante takes pains to expose the parts of this persona that survived her transition, owning up to bouts of snobbery toward trans women who wear polyester or write their online confessions in “some script font with no paragraph breaks and maybe no capital letters” or choose cliché background music for their transformation videos. She seems to have had these feelings almost from the start of her awareness that she was a girl, around the age of nine. She remembers associating the desire to change gender with a perversion, embarrassing on an aesthetic level above all—men in ladies’ underwear, French maid or nurses’ uniforms, “pinafores and pigtails”: “There was nothing wrong with any of that of course, nobody got hurt, but it was all just so limited, so superficial, so cheap, so squalid. What made me different—because I always had to be different—was that I actually wanted to be a girl, not just look or act like one.” She writes near the end of I Heard Her Call My Name that, in matters of gender presentation, “I’m not really very concerned with what you might call authenticity, at least these days. I’m more preoccupied with taste, because taste has always been the way I demonstrate that I’m as valid as anyone else.”

Therein lies a clue to the mystery of how Sante’s vocation as a writer did so little to help her answer that other call invoked in the book’s title. Writing was no more a free space for play and self-expression than gender is. She represents her life as a fraught, embattled adventure of self-fashioning, played out on the page as much as anywhere else. To write was to invite severe scrutiny, as she learned during the era when her fervently Catholic mother searched her “room on any pretext and read every bit of writing she found there,” and when, aged 14, she began unsuccessfully submitting to magazines, signing herself Mr. Luc Sante “so they’d know I was both male and adult.” She recalls how much of her adulthood was spent shoring up a pose, “trying at all times to mount a production titled Luc”: “I curated my surroundings as a kind of rebus of cultural signs, displaying faceup those items that would send a message about my judgment and my possession of secret knowledge,” she writes. “Barring grocery lists, I never wrote anything down that I would have been unwilling to have published.”

In a certain sense, Sante was stuck living the wrong life—the one she felt capable of making at the time out of what she was given. Maintaining the “production titled Luc” evidently required a lot of energy, yet that process formed her, and she has few real illusions about what might have been possible without it. She notes, “I naturally regret my lost girlhood, yearn hopelessly for it, although I’m drawn up short when I actually imagine what being my parents’ daughter would have been like.” Among other things, it would have precluded the scholarship to a New York City Jesuit high school that provided an initial escape from home. “Would I have had to get married to get away from them?”

Sante catalogs in detail the anxious work undertaken by a perennial outsider, figuring out how to be an American, a man, a sophisticate, a woman, a trans person—all the minute codes of dress, imagery, language, mood, tone. The insights this book yields into gender dysphoria and transition are also always applied to other kinds of discomfort, yearning, exploration. There is an almost old-fashioned quality to Sante’s predicament—the book offers some of the strange virtues of a previous generation of trans memoir, such as Jan Morris’s 1974 Conundrum, which situates its author as perforce the lone questing heroine of an epic, surveying a starkly binary landscape that has altered considerably in the years since. Of course, Sante is in a position to describe witnessing and belatedly participating in that transformation, discovering a new world of trans literature and collective life that she’d somehow contrived to know little about until her “egg cracked.”

By Sante’s usual standards, this book feels disarmingly frank. She writes about the truth, and announces, “I am the person I feared most of my life.” She reproduces, apparently verbatim, the coming-out email she sent to friends and acquaintances in February 2021 and later adapted for a viral essay in Vanity Fair. She also includes the elaborate retraction she composed two weeks later in a panic but didn’t send, and the more honest compromise email she settled on in mid-March. I say verbatim because she goes so far as to share specific edits she incorporated to the original text, such as the suggestion of a trans woman she barely knew that she amend “I trembled from my shoulders to my crotch,” substituting for crotch “that Victorian euphemism, ‘belly.’”

The use of these emails might at first give an impression of unfiltered intimacy, not so much because they began as nominally private communications, but because they allow us to witness Sante’s epiphany in close to real time, amid the “pink cloud” of early transition. The urgent clarion style of the first email, in particular, conveys the force of her relief and euphoria. But there is nothing artless here. Even the book’s seemingly simple structure, interspersing sections on Sante’s childhood, coming of age as a writer, midlife, with those on each phase of her transition so far, creates eerily repetitive overlaps and echoes and contradictions—double takes that put the reader through some approximation of the hesitancy and impatience and grandiosity and self-loathing, the halting, confused, frustrating, humbling experience of Sante’s change.

She wrestles with a sense of not deserving to be among the women she admires, understanding gender as a spectrum yet also wanting “the emotional range of a woman,” and the reflexively self-punishing reluctance to come out to her online chat group because of how unconditionally supportive they were likely to be—“like jumping out of the window into a tub of marshmallows.” (And she notes the far more troubled reactions she received from supposedly cis men, including a significant number who told her they had the same feelings but planned never to act on them.) She depicts the struggle of a habitually binary-thinking person who doesn’t fit into her own schema. Like Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, this is in part an epistolary memoir that captures a fervid love affair with oneself, but like that book it also treats its material with the retrospective zeal and precision of a detective.

The self-portrait Sante draws is in fact much more elliptical than it first appears—and not only because, one senses, of the desire to shield some of the people who have shared her life. The book is illustrated with a series of images of Sante as a girl and woman, from childhood to the present, many created by feeding old photos into the app. They are a painfully moving testament to the life she didn’t get to have, and their immediacy draws attention to the relative restraint of the text around them. Her approach here is at times reminiscent of the Didion of The Year of Magical Thinking, examining from the outside the workings of her own mind in extremis. Ruefully recalling the remark of someone who hoped transition might inaugurate a new openness in her writing, Sante declares herself an incurable emotional “minimalist.”

What feels most poignant is the clear continuity with Sante’s earlier work. Just as in Low Life and The Other Paris she used partial maps and letters and pamphlets found in flea markets to conjure the “fugitive lyricism” once found in the impoverished underbellies of cities, in I Heard Her Call My Name she draws on a seductively incomplete archive, the material evidence of her own life. As well as those emails and photographs, there are notebook entries; the death certificate of a would-have-been older sister, Marie-Luce, whose stillbirth haunted Sante’s fraught relationship with her mother; the newspaper caption announcing her the winner of a local school prize that, thanks to a misprint, marked the public appearance of “Lucy Sante” several decades avant la lettre; and of course her published works.

She marvels at the imagery that slipped by her “internal censor” in a prose poem she wrote in 1978. Subjected to a close reading, it’s a vision of the “alchemical transformation from male to female.... And is that a clitoris in the last sentence?” But the key, and characteristic, challenge she sets herself is to dig up and parse the evidence that never made it into any concrete form, the stuff of fantasy and rumination that might by now feel untraceable, a “flood of matter—knowledge, speculation, dreams—that had been confined so long it had fermented and become hallucinogenic.” She tracks down the esoteric reading she did in secret, getting rid of the books and clearing her browser history afterward. Memory, too, she treats like a physical archive to be explored and interpreted:

Every time I’d go to confession I’d confess the same two sins: disobedience and lying. That dates my trouble with my parents back to an early age, because I don’t remember ever confessing to anything else, and just the appearance of the word disobedience sets off an audio clip in my head of shouting and screaming.

All those habits of mind, the way Sante fashions her sentences and the parallel accretive and analytic methods she has developed over the decades to approach her subject matter, searching out a path through influences and desires and revulsions, are, it turns out, the closest thing to a self that can be examined and shared—in silhouette. Literary style, like gender expression, is always part posturing or “playacting,” part aspiration, and by the same token discloses something more elusive and resonant, being that place where the conscious and unconscious meet.