Inside Big Oil’s Plot to Keep Their Emissions Confidential

The Securities and Exchange Commission on Wednesday voted 3–2 to finalize a rule on what companies disclose about their greenhouse gas emissions and how climate change stands to impact their business. On its face, that wouldn’t seem to be much cause for alarm. Companies are already required to disclose information on their management structures, overall financial health, and the kinds of risks facing their business. Large segments of the oil and gas industry, though, as well as their beneficiaries in the Republican Party, are treating the possibility of having to disclose climate-related information as if it were an existential threat. And as a result, the SEC’s rule is much weaker than it could have been.At an industry conference last month, Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Western Energy Alliance, a trade association for oil and gas producers, laid out her group’s strategy for stopping new regulations and administrative actions in their tracks; the main goal, she emphasized, was to kill any version of the SEC’s climate disclosure requirements. At the North American Prospect Expo, or NAPE, Summit for the energy industry in Houston early last month, she described the potential SEC rule as one of several attempts to “decapitalize, defund, or de-bank our industry.” An audio recording of the speech, which was open to all attendees, was provided to The New Republic by an audience member who asked to remain anonymous so as not to jeopardize future attendance.On some level, industry pressure has already worked: The SEC rule that came to a vote on Wednesday was considerably weaker than the version that was first proposed in March 2022. It lacked the strongest part of the original proposal: that companies be required to disclose what are known as Scope 3 emissions. Those are the emissions linked to products it purchases from third parties, activities like business travel, and the use of its products by consumers. Scope 3 emissions account for as much as 90 percent of a given company’s emissions. Fossil fuel executives and lobbyists’ heated opposition to being required to disclose these emissions is a big part of why that component was dropped. SEC Chair Gary Gensler has said that the rule received 24,000 comments during the required public comment period that ended this morning—the largest ever number of comments filed on a single proposal. By the time the rule was released, even disclosing Scope 1 and 2 emissions—roughly speaking, those generated by corporate operations—was in question. It will now only be required of larger, SEC-registered companies—about 40 percent of America’s 7,000 public companies registered with the SEC—that determine these disclosures are “material” to investors.David Arkush, director of the watchdog group Public Citizen’s Climate Program, and an expert on climate-related financial regulation, described Scope 3 requirements as “the most concrete, quantitative, decision-useful information that was in the proposal. It’s [a] really big disappointment that it’s been dropped. It’s ultimately better to finish this rule than not,” he added, “but losing Scope 3 is a big step backward, even though it’s still a step forward from the existing state of affairs.” Many advocates also see the SEC’s watering down of disclosure rules as a response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia v. EPA last summer, which raised the prospect of a wide-reaching challenge to agency rulemaking.Even before the results of the rule were announced, Sgamma said industry groups were eager to sue over the rule. “People are standing in line to litigate that,” she said, adding that the Alliance probably wouldn’t mount its own legal opposition given how many groups are likely to join the fray. Asked over email whether there was any version of the final rule that her group or the industry at large might be happy with, she said, “No. SEC has no statutory authority to regulate climate change.”In her speech last month, Sgamma elaborated on why her group and others see disclosure requirements as so dangerous. “If you can make an oil and gas company look like it’s emitting too much” carbon dioxide emissions, Sgamma warned, “eventually that becomes a reason to say, ‘Oh, you can’t fund that because it emits CO2 emissions.’” Despite the fact that U.S. oil and gas companies have enjoyed record profits and levels of production under the Biden administration, industry groups have consistently complained that the White House is conspiring to undermine their industry’s reputation on Wall Street. In reality, these companies have themselves to blame: Over the past decade, shale drilling companies, especially, burned through investor cash as they collectively looked to extract as much oil and gas as possible. Many firms—particularly the smaller and midsize drillers that predominate the Western Energy Alliance’s membership roster—struggled to make a profit. After years of watching their money go up in smoke, frustrated investors started to

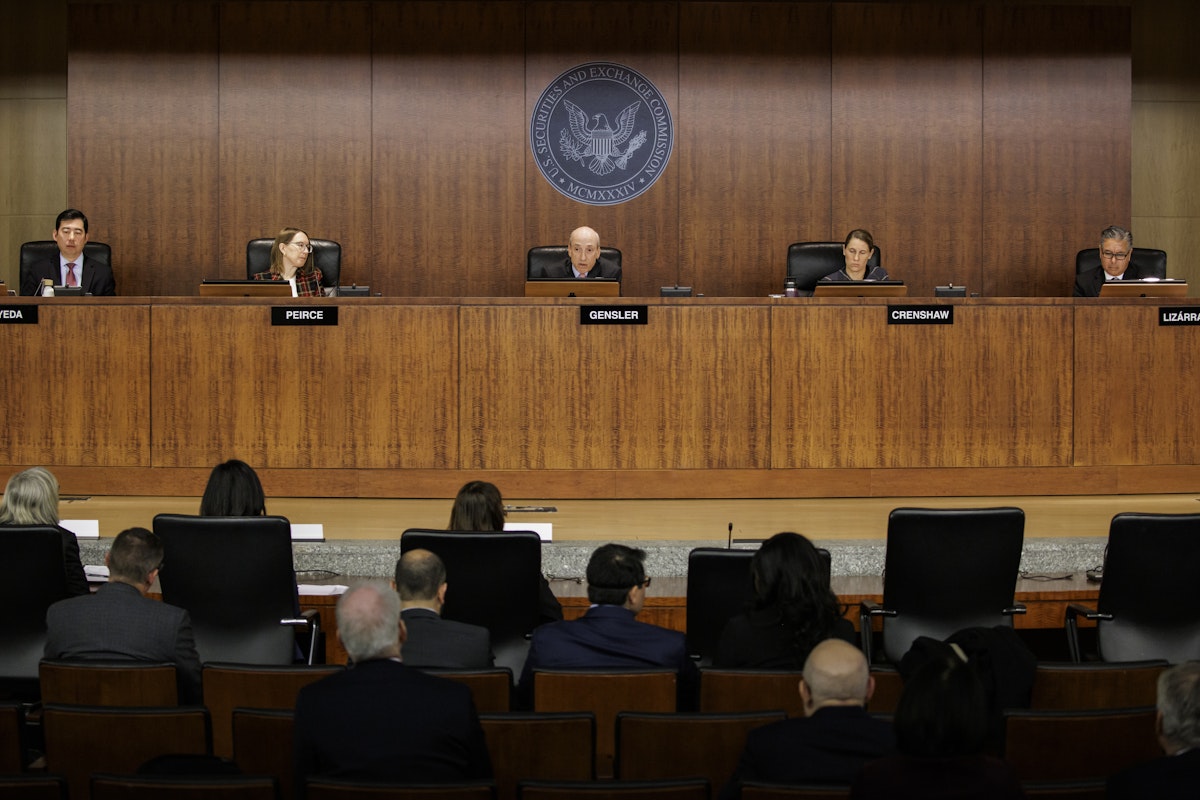

The Securities and Exchange Commission on Wednesday voted 3–2 to finalize a rule on what companies disclose about their greenhouse gas emissions and how climate change stands to impact their business. On its face, that wouldn’t seem to be much cause for alarm. Companies are already required to disclose information on their management structures, overall financial health, and the kinds of risks facing their business. Large segments of the oil and gas industry, though, as well as their beneficiaries in the Republican Party, are treating the possibility of having to disclose climate-related information as if it were an existential threat. And as a result, the SEC’s rule is much weaker than it could have been.

At an industry conference last month, Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Western Energy Alliance, a trade association for oil and gas producers, laid out her group’s strategy for stopping new regulations and administrative actions in their tracks; the main goal, she emphasized, was to kill any version of the SEC’s climate disclosure requirements. At the North American Prospect Expo, or NAPE, Summit for the energy industry in Houston early last month, she described the potential SEC rule as one of several attempts to “decapitalize, defund, or de-bank our industry.” An audio recording of the speech, which was open to all attendees, was provided to The New Republic by an audience member who asked to remain anonymous so as not to jeopardize future attendance.

On some level, industry pressure has already worked: The SEC rule that came to a vote on Wednesday was considerably weaker than the version that was first proposed in March 2022. It lacked the strongest part of the original proposal: that companies be required to disclose what are known as Scope 3 emissions. Those are the emissions linked to products it purchases from third parties, activities like business travel, and the use of its products by consumers. Scope 3 emissions account for as much as 90 percent of a given company’s emissions. Fossil fuel executives and lobbyists’ heated opposition to being required to disclose these emissions is a big part of why that component was dropped. SEC Chair Gary Gensler has said that the rule received 24,000 comments during the required public comment period that ended this morning—the largest ever number of comments filed on a single proposal. By the time the rule was released, even disclosing Scope 1 and 2 emissions—roughly speaking, those generated by corporate operations—was in question. It will now only be required of larger, SEC-registered companies—about 40 percent of America’s 7,000 public companies registered with the SEC—that determine these disclosures are “material” to investors.

David Arkush, director of the watchdog group Public Citizen’s Climate Program, and an expert on climate-related financial regulation, described Scope 3 requirements as “the most concrete, quantitative, decision-useful information that was in the proposal. It’s [a] really big disappointment that it’s been dropped. It’s ultimately better to finish this rule than not,” he added, “but losing Scope 3 is a big step backward, even though it’s still a step forward from the existing state of affairs.” Many advocates also see the SEC’s watering down of disclosure rules as a response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia v. EPA last summer, which raised the prospect of a wide-reaching challenge to agency rulemaking.

Even before the results of the rule were announced, Sgamma said industry groups were eager to sue over the rule. “People are standing in line to litigate that,” she said, adding that the Alliance probably wouldn’t mount its own legal opposition given how many groups are likely to join the fray. Asked over email whether there was any version of the final rule that her group or the industry at large might be happy with, she said, “No. SEC has no statutory authority to regulate climate change.”

In her speech last month, Sgamma elaborated on why her group and others see disclosure requirements as so dangerous. “If you can make an oil and gas company look like it’s emitting too much” carbon dioxide emissions, Sgamma warned, “eventually that becomes a reason to say, ‘Oh, you can’t fund that because it emits CO2 emissions.’”

Despite the fact that U.S. oil and gas companies have enjoyed record profits and levels of production under the Biden administration, industry groups have consistently complained that the White House is conspiring to undermine their industry’s reputation on Wall Street. In reality, these companies have themselves to blame: Over the past decade, shale drilling companies, especially, burned through investor cash as they collectively looked to extract as much oil and gas as possible. Many firms—particularly the smaller and midsize drillers that predominate the Western Energy Alliance’s membership roster—struggled to make a profit. After years of watching their money go up in smoke, frustrated investors started to demand that companies focus on turning a profit rather than rapid-fire production. That was followed by the Covid-19 pandemic, when demand for fuel crashed amid worldwide travel restrictions. While fossil fuel executives’ fortunes have turned around dramatically in recent years, they’re still mostly blaming any real and (often) imagined woes on Democrats.

Throughout this period, the Western Energy Alliance itself has faced declining membership. In 2021, E&E News reported that the group had lost a third of its members. As part of a short-lived public relations push to burnish its green credentials, BP left the group, along with two other trade associations that have opposed climate policies. According to BP, the company chose to leave the Alliance over its opposition to federal methane regulations. Over email, Sgamma blamed her group’s decline in membership on consolidation within the industry that continues to “shrink the pool of Western companies.” She said, as well, that companies “continue to have trouble being banked or raising capital” and called that “a function of ESG pressure, not true market forces.” ESG is an abbreviation for the “environmental, social, and governance” investment principles that Republicans have targeted at the state and federal level over the last several years. (SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce, a Donald J. Trump appointee, parroted the anti-ESG movement’s favorite talking points as she spoke during the SEC meeting Wednesday morning, claiming any disclosure requirements at all would open the door for “ethical investors” and “special interest groups to achieve what they cannot accomplish through normal political channels.”)

Sgamma’s talk outlined three “models,” or strategies, for tanking everything from regulations to presidential appointments. Citing the injustice of everything from disclosure requirements to methane regulations, tailpipe emissions standards to closing off federal lands to oil and gas production, she proposed action. “We could sit here and have a little parade of misery and feel bad about ourselves, or we could look at real solutions,” she told the crowd.

“Whatever happens with the election we will still have basically 50-50. We’re maybe gonna take the Senate, lose the House, as far as Republican,” Sgamma said, adding that “nothing’s gonna come out of Congress for the next two years. So this political environment is going to remain a dumpster fire, but we can still win.” While she appeared to identify her organization with Republicans, Sgamma went on to clarify that the Western Energy Alliance is officially nonpartisan.

“It’s no secret the majority of the Democratic Party is hostile to American oil and natural gas. We like divided government, as one-party rule is bad for American energy,” Sgamma wrote over email when asked to clarify where her group stands vis-à-vis partisan politics. “I was referring to the dumpster fire of our politics as a whole, from the mismanagement of Republicans in the House, the current hostile Administration, to a potential chaotic Trump Administration.”

In Houston, Sgamma described her first “model” for political action, however, as “fairly partisan.” It revolves around leaning on Republican-controlled state officials—including attorneys general and treasurers—working with Republican-controlled congressional committees. Sgamma brought up the example of the New York Stock Exchange’s attempt to create a new asset class for so-called “natural assets,” which it recently withdrew from consideration by the SEC. The failure of that proposal, Sgamma argued, was thanks to a pressure campaign spearheaded on the one hand by Utah Treasurer Marlo Oaks—who corralled 23 state treasurers and comptrollers to oppose the proposal—and, on the other, by the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations. The subcommittee, chaired by Republican Paul Gosar, will hold its second hearing this week on the topic. Congressional Republicans also filed legislation to prevent the SEC from ever advancing similar proposals.

Sgamma’s “grassroots model,” by contrast, is better suited to be used “for things that are easy to understand for the public,” like federal regulations regarding gas stoves, fuel efficiency, and tailpipe emissions—“all these rules trying to tell you which type of car you can drive, that you can’t use your gas stove,” she elaborated. (None of the rules Sgamma referenced would actually require consumers to purchase particular kinds of appliances or electric stoves. Instead, they require manufacturers to sell products that comply with certain emissions standards.) Such “grassroots” efforts, she added, rely on collaborating with other industries and trade associations. “Working with stakeholders is really important, because if we just say things as an industry nobody cares. We’re not a sympathetic industry, right? We need to work with others,” Sgamma told conference attendees.

The final model Sgamma presented she dubbed the “bipartisan” model. “You could call it the Senator Joe Manchin model because he’s been key to it,” she said, though she noted there were several vulnerable Democrats—including Montana Senator Chuck Testa, Nevada Senator Jackie Rosen, and Pennsylvania’s Bob Case—who were “perhaps pick off-able on some of these issues as well.” In November, Manchin sent a letter to Gensler, the SEC chair, calling on him to postpone rulemaking on climate risk and emissions disclosures and extend the public comment period. Manchin’s website also catalogs his “efforts to block the Biden Administration’s ESG policies.” That includes leading an effort to overturn a relatively anodyne Labor Department rule clarifying that federal pensions managers are allowed to consider ESG factors when making investment decisions.

Now that the SEC rule has been finalized, it’ll only be a matter of time before Republicans start filing lawsuits in sympathetic federal courts to bring it down. Arkush, of Public Citizen, said it’s also likely that groups who supported more comprehensive requirements could sue too, in courts less packed with GOP appointees. This new rule’s future could come down to which judges end up hearing those challenges. It’s very unlikely, though, that companies will be able to escape disclosure requirements now in place in the European Union, California, and other jurisdictions. For now, as ever, the fossil fuel industry and the politicians it donates to will keep trying to deny the inevitable.