Inside Ukraine’s lost sovereignty battle that created world’s favorite Christmas song

A century ago, Ukraine's desperate fight for independence from Russia led to the boldest soft power gamble in history — and gave birth to the world’s most iconic Christmas hit.

Billions of people worldwide don’t celebrate Christmas, but no one can escape this song.

Over the last century, this Christmas tune has grown into winter’s global anthem, with just the opening notes sprinkling holiday spirit whether you celebrate the season or not.

Since its debut in the US in 1922, it has been recorded in nearly 150 arrangements and become one of the world’s most performed songs, making its way into more than 250 TV shows and over 100 holiday ads – including Christmas classics like Home Alone and iconic Coca-Cola commercials.

If monetized, it could have banked $130 million — drawing 2-5 times more plays than any Christmas hit in history, according to Forbes.

However, since its birth over a century ago, this song has lived as a public treasure – and Ukraine’s greatest cultural gift to the world.

Over the decades, many have fallen under the spell of Carol of the Bells — a marketing powerhouse and intimate experience that ushers millions into each new year with fresh hope.

Yet, while countless listeners around the world are enchanted by this magic tune, few are aware of its Ukrainian history — or that the world’s favourite Christmas song owes its rise to a daring century-old diplomatic mission: to rescue Ukraine’s independence.

A winter anthem with the promise of spring

Before winning the hearts of a global audience, Carol of the Bells was known as Schedryk — the original Ukrainian title under which the century-old folk song first made its public debut.

Derived from the phrase “shchedryi vechir” (bountiful evening), this folk song originates from pre-Christian New Year celebrations, which the ancestors of modern Ukrainians held in March to celebrate the arrival of spring, marked by the return of the first swallows.

This millennia-old tradition gave rise to the Ukrainian shchedrivky genre — folk songs sung to bless households with abundant harvests and prosperity in the year ahead, a promise beautifully captivated in Shchedryk’s original lyrics.

Shchedryk, shchedryk, shchedrivochka,

A little swallow flew in,

Began to twitter, calling the master,

“Come out, come out, O master,

Look at your sheepfold,

The ewes have all lambed,

And the little lambs are born.

Your goods are great,

You’ll have plenty of money,

If not money, then chaff,

You have a dark-eyebrowed wife.”

Shchedryk, shchedryk, shchedrivochka,

A little swallow flew in.

First captured by Ukrainian folklore collectors in the 19th century, this song eventually found its way into the hands of budding Ukrainian composer Mykola Leontovych, then a music teacher, in the early 1900s.

The melody consumed Leontovych for six years of intense refinement. But that was just the start. As he rose to prominence with over 150 choral works, Leontovych couldn’t let go of Shchedryk, crafting five disctinctive arrangements over the next 19 years.

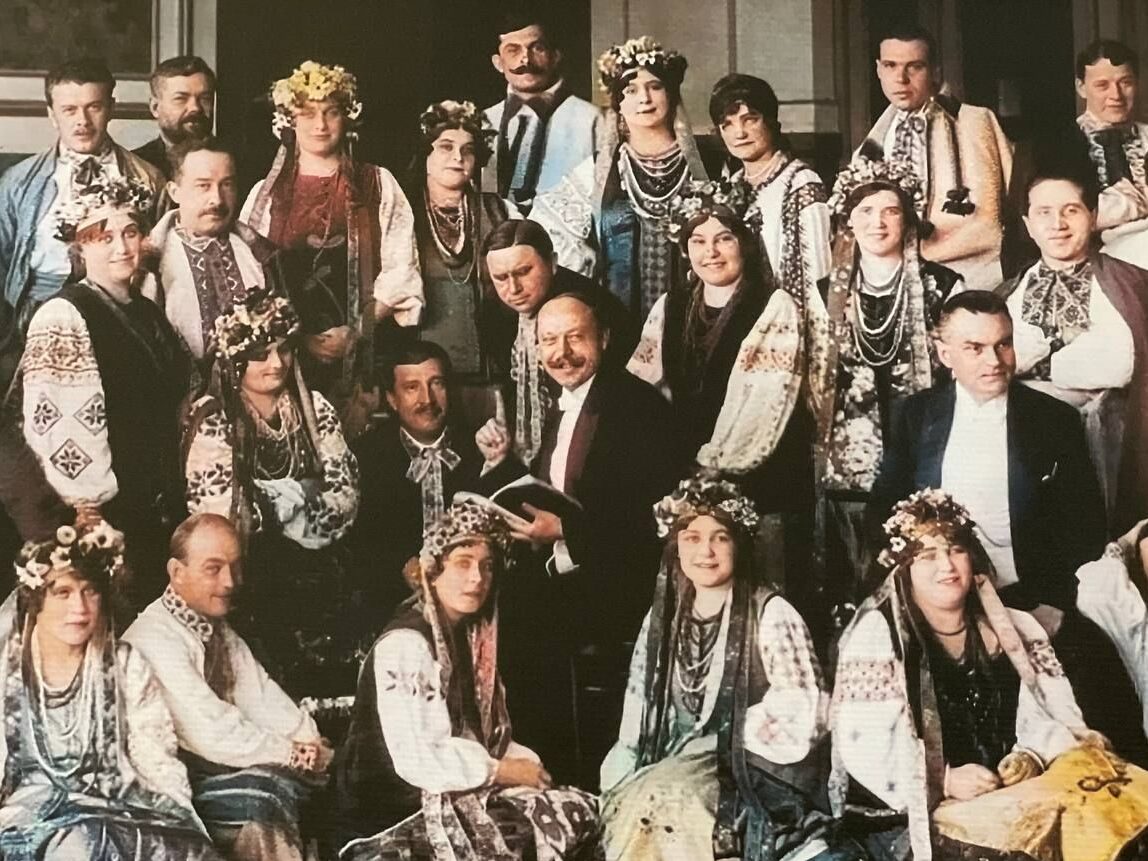

Leontovych wasn’t finished with the song when it first made its debut. In 1916, he passed his notes to Oleksandr Koshyts, a renowned Kyiv conductor, who was instantly captivated by its magic. Eager to share this musical treasure, Koshyts brought Shchedryk to life at a Christmas concert on 25 December 1916 in Kyiv, a city still under the grip of the Russian Empire, leaving the audience spellbound.

This was the first time a spring folk song would be reborn as a Christmas sensation — and the calmest debut in a whirlwind journey that would propel it to global stardom.

The boldest soft power gamble in history

The melody’s peaceful premiere came at history’s edge — within three months, the war-weary Russian Empire would splinter into revolution, unleashing a fierce civil war for its remains.

In January 1918, Ukrainians boldly declared an independent state — the Ukrainian People’s Republic. But their newfound freedom was immediately threatened by the chaos of World War I and the looming Russian menace. The Bolshevik forces, fresh from taking the former empire’s capital, charged westward, bent on reclaiming lost territories and crushing Ukraine’s fragile independence.

Within a year, the situation had grown dire: Russian forces had captured much of Ukraine’s east and were now closing in on Kyiv. In the face of this existential crisis, Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura took a daring diplomatic gamble. He made the decision to send Koshyts’ choir — the nation’s finest — into the heart of Europe, where the continent’s future teetered on the edge.

In January 1919, the world braced for a pivotal moment — the Paris Peace Conference, where the map of Europe would be redrawn, carving up the empires shattered by recent World War I.

Petliura hoped to seize the moment and introduce the fledgling Ukrainian state to world leaders, hoping to gain allies against advancing Russian forces. Yet, after centuries under Russian rule, Ukraine was a stranger to the global stage, unknown and dismissed by Western powers.

The situation grew more dire as Russian influence surged. Following the October 1917 Revolution, waves of Russian émigrés flooded Europe, relentlessly campaigning to restore the Russian Empire – and leaving no space for the new nations rising from its collapse.

As world powers debated Ukraine’s future, Petliura bet it all on a cultural offensive. He sent Koshyts’s premier orchestra, now called the Ukrainian Republican Capella, abroad, with Shchedryk — already the brightest star in their repertoire — leading the charge.

Orchestrating sovereignty

Just three weeks before the Paris Peace Conference was set to start, the Ukrainian People’s Republic organized a tour for Koshyts’ choir across European capitals, granting it an astonishing funding — equivalent to nearly $20 million today — from its rapidly dwindling treasury.

However, the tour never went as planned, and the grand cultural mission turned into a desperate escape.

As Russian troops closed in on Kyiv, the choir fled on the last train out, rehearsing their program on the run. The Russian assault forced Petliura’s government to retreat westward. Leontovych, the creator of Shchedryk, sought refuge in a besieged city as Russian troops leveled Kyiv, hunting down Ukraine’s cultural elite.

The choir pressed on despite the turmoil, and four months later, the high-stakes tour finally kicked off. In May 1919, Shchedryk made its European debut at Prague’s National Theatre, earning critical acclaim and propelling Ukrainian culture from obscurity to sudden, dazzling fame.

“The Tsarist regime recognised the inherent power of Ukrainian songs and suppressed them wherever possible,” wrote the Czech newspaper Tribuna. “Now, however, Ukrainian songs are free and will resound across Europe.”

Despite their triumph in Prague, the choir couldn’t gain access to Paris, where they desperately needed to be before the peace conference ended in May. Denied visas for Ukraine’s unrecognized status, they took matters into their own hands, showcasing Ukraine’s cultural strength in every Western European city they could reach.

By the time they arrived in France in the summer of 1919, staging a defiant triumph despite Russian protests, the diplomatic cards had been already dealt. The Versailles Treaty had divided western Ukraine’s territories, once part of the collapsed Austro-Hungarian Empire, and handed them over to the newly-formed states of Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia that rose from its ruins.

To the east, Russian forces had tightened their grip, and Ukraine’s independence began to crumble across the rest of the fledgling nation.

With no homeland to return to, the acclaimed choir had no choice besides touring. Between 1919 and 1921, its 80 voices carried Shchedryk through 45 cities in 10 European countries, with the melody finding new life in seven languages.

In January 1921, as the Ukrainian National Capella basked in European glory at Paris’s Élysée Palace, tragedy struck. Back in Ukraine, Mykola Leontovych — the mastermind behind their crown song — fell victim to Russians. Pretending to be a traveler seeking refuge, a communist agent shot the composer in his sleep and ransacked his home before disappearing into the night.

However, his murder was just the beginning of Russia’s decade-long reign of terror in Ukraine.

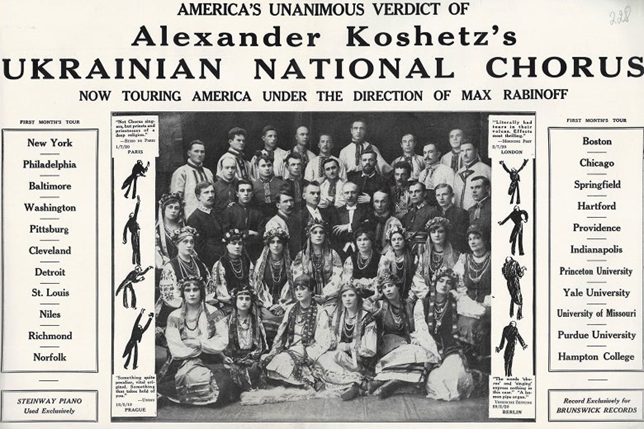

By the time the world-famous orchestra crossed the Atlantic to premiere Shchedryk at Carnegie Hall in 1922, their homeland had already vanished from the map, firmly occupied by the Russian forces. Two months later, on 30 December, the USSR was born — and the performers of the soon-to-be Christmas classic became exiles overnight.

With no country to call home, the Ukrainian Republican Capella – now the worldwide sensation – toured 115 cities across 36 US states, before taking their journey to Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cuba.

By the end of their odyssey in 1924, Koshyts’s orchestra had enchanted 150 cities, preserved their American debut on vinyl, drawn a record-breaking crowd of 40,000 in Mexico, and garnered 2,000 mentions in the international press, planting Ukrainian culture across three continents.

“No propaganda could be more effective in recognizing the Ukrainian nation. No matter how much its existence is denied, your choir proves that this nation has a musical soul of unmatched strength,” wrote Charles Seignobos, French historian and professor at the Sorbonne.

The Ukrainian choir soared to fame beyond Petliura’s wildest diplomatic dreams — but at a heartbreaking price. In 1924, Koshyts disbanded the choir and settled in the US and Canada, where he spent the next two decades longing to return to Ukraine — a return that was never meant to be.

Two years later, in May 1926, a Soviet agent tracked down Symon Petliura – now exiled in Paris – and gunned him down with seven bullets. The communist regime now exterminated his former supporters in Ukraine, and the choir, scattered across the world, had no way back. Ukraine’s independence was crushed for the next seven decades.

But Shchedryk’s journey wasn’t over. In 1936, Peter Wilhousky, an American composer of Ukrainian descent, gave the song its immortal English voice as Carol of the Bells. After its NBC radio debut, the newsroom was flooded with letters from listeners requesting the sheet music — and a Ukrainian folk song began its ascent into the heart of global Christmas classics.

While Shchedryk soared to international fame, its homeland lay silent. Three years earlier, in 1932-33, the same Soviet regime that had driven the song into exile unleashed the Holodomor, a man-made famine that killed nearly 4 million Ukrainian peasants — the very keepers of the folk culture that birthed the iconic melody.

The Great Terror followed in 1937, destroying Ukraine’s political and cultural elite of their greatest cultural export.

One mission, two chances

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, Schedryk has been given a second opportunity to complete the historic mission it was entrusted with a century ago.

In 2022, a century after its debut in New York, the song returned to Carnegie Hall for the Notes from Ukraine solidarity concert, which brought together over 2,800 guests and 5,000 online viewers. The iconic Christmas anthem was performed by the Ukrainian choirs, including Kyiv’s oldest professional children’s choir, whose 56 young performers had arrived in the US fleeing the Russian invasion — just like their predecessors.

This time, Shchedryk journey took a different turn — after New York, Shchedryk carried its magic to concert halls in Denmark. Yet, despite the change in direction and the passing of time, Ukraine’s timeless carol retained its power — and encountered the same challenges it had faced a century ago.

“In the circumstances of war, every day for the choir is an existential battle,” said Marianna Sablina, the choir’s conductor.

The only difference now is that the Shchedryk message works both ways, with the world embracing it as a symbol of solidarity with Ukraine. In December 2022, NATO soldiers performed Carol of the Bells at a NATO base in Latvia in support of Ukraine, with troops from Denmark, Latvia, Spain, and the United States joining in.

Furthermore, various organizations have leveraged the song’s global reach to drive donations for Ukraine. In 2022, the Estonia-based NGO Slava Ukraini relied on the song to raise over €3.5 million for essential supplies and medical equipment for Ukraine’s frontline regions.

A century after it left Kyiv, Shchedryk’s mission endures, echoing Ukraine’s spirit across the globe.

Read also:

• Russian web designer claims Ukrainian typography pioneer as “great Russian artist”

• From bullets to songs: Ukraine’s top artists fight back in English

• Soldiers of Song: Ukraine’s musicians battle Russian “cultural genocide” through music

• Can Ukraine cancel Russia’s imperial history? Odesa debates decolonization