Joe Biden Is Running on Roe. It’s Not Enough.

“It’s simple,” Joe Biden tweeted. “Restore the Protections of Roe v. Wade Once and For All,” read the image below the tweet. Biden’s communications team posted this on Monday, the fifty-first anniversary of the day the Supreme Court issued its landmark abortion opinion that made its plaintiff’s pseudonym synonymous with reproductive rights. But Roe was never the bottom line on abortion, and it was never simple. The Biden 2024 campaign’s narrative about it is simple: Biden this time is running on abortion. Or more precisely, he is running on Roe.If Joe Biden wants to run on abortion, he ought to try using the word sometimes, to start. His vice president, former prosecutor and Senator Kamala Harris, has used it more often, referring interchangeably to “Roe,” “abortion,” and “reproductive freedom”—a term with roots in activist movements, and one you will find in the opening lines of media coverage of the Biden-Harris 2024 campaign. These activist movements have long pushed the Democratic Party, mainstream reproductive rights groups, and “pro-choice” groups to expand their professed support for what was too often shorthanded as “a woman’s right to choose.” They knew for decades that Roe was in peril, in part because some of its most influential defenders failed to take on a full spectrum of political and legal issues concerning abortion, far beyond Roe. So now that Roe has been overturned, we ought to ask: When Democrats like Biden run on abortion, what precisely about abortion do they intend to defend? The coalition of conservative and Christian-right groups that overturned Roe, of course, did not go home in 2022 content with their victory. Their next lines of attack are far from secret, and in fact have been detailed in writing. Democrats who want to defend reproductive rights should probably look to policies that would stop these strategies in their tracks. Instead, they seem to be relying on “codify Roe”—relying on the same inadequate, constrained “right” to abortion in some cases that has proven so easy to overturn, and which has now laid the groundwork for new right-wing attacks.One of the most dangerous anti-abortion strategies the groups who campaigned for Roe’s reversal are now pursuing is a nationwide ban on all abortion. They claim that the groundwork for a national abortion ban has already been laid by the Comstock Act, passed in 1873, which in part made it illegal to mail any instrument used for performing an abortion. Despite the law’s vintage, we still live in a country in which the mail exists. As legal scholars David S. Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouché argue, “Because virtually everything used for an abortion—from abortion pills, to the instruments for abortion procedures, to clinic supplies—gets mailed to providers in some form, this interpretation of the Comstock Act could mean a nationwide ban on all abortions, even in states where it remains legal.” Few people have paid attention to this threat. But anti-abortion groups have, and their Comstock-as-abortion-ban arguments have won some support. As Cohen, Donley, and Rebouché point out, “federal courts in Texas and the Fifth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals have already accepted their interpretation.”The Comstock Act has long been viewed as all but a dead letter, after decades of successive court decisions hacking away at most of it. When the act was last updated during the Clinton administration, the attorney general told Congress she would not defend or enforce its abortion-related provisions. But they remain on the books for any abortion-hostile administration to enforce. Enforcing Comstock is already part of Project 2025, a plan devised by the Heritage Foundation and dozens of other groups to enact day-one change in a coming conservative administration. “If we got Donald J. Trump back in the White House, he could end abortion in every single state in America, by enforcing the Comstock Act,” said Right to Life East Texas director Mark Lee Dickson this week. To its credit, after Roe was overturned, the Biden administration did take some steps toward countering this potential application of the Comstock Act. In December 2022, the Department of Justice issued a memo stating its position that the Comstock Act does not prohibit mailing abortion pills. Jen Klein, director of the White House Gender Policy Council, called the Comstock Act “super dangerous” in remarks to press this week, particularly because it has a five-year statute of limitations. That means, should an abortion-hostile administration choose to do so, it could prosecute in the future any alleged violations now. Klein also noted the broader anti-abortion play—that right-wing groups “don’t think they need to pass a national abortion ban” because they think they can get courts to rule that the Comstock Act is functionally a national abortion ban.That strategy will come before the Supreme Court this spring, in a case that will be decided before Election Day. Alliance for H

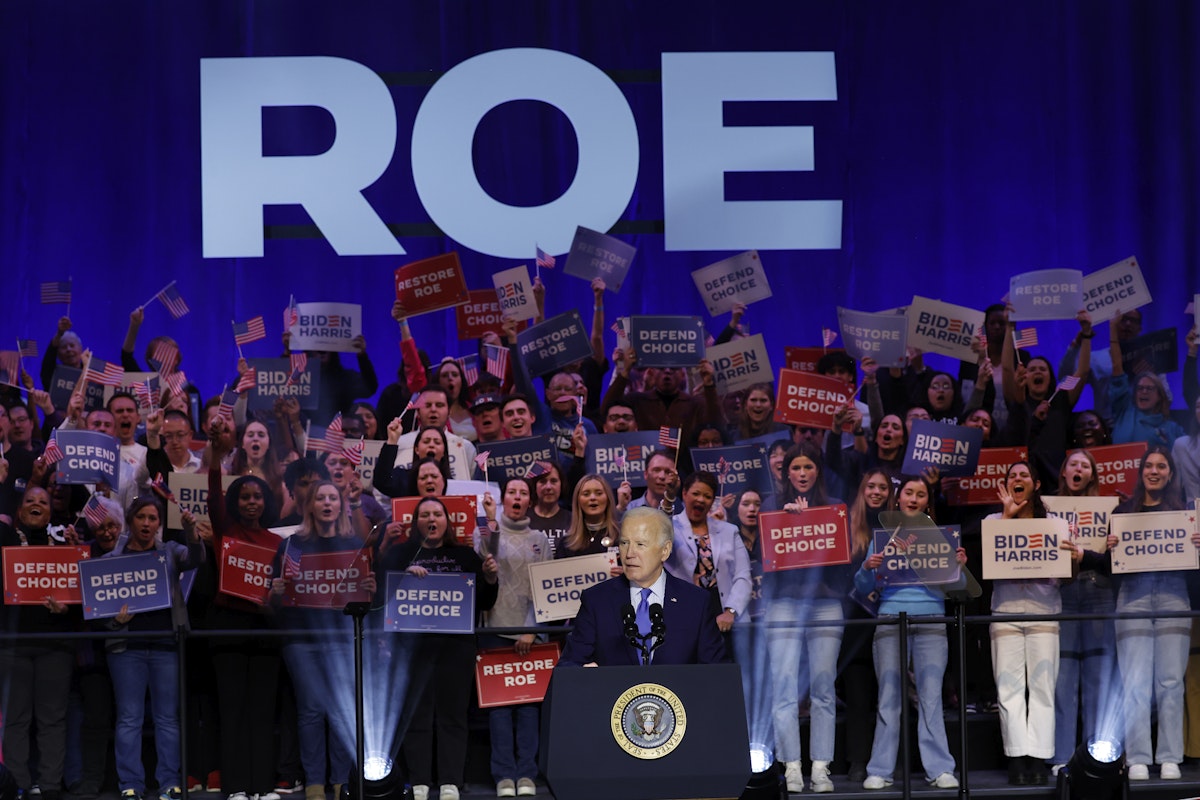

“It’s simple,” Joe Biden tweeted. “Restore the Protections of Roe v. Wade Once and For All,” read the image below the tweet. Biden’s communications team posted this on Monday, the fifty-first anniversary of the day the Supreme Court issued its landmark abortion opinion that made its plaintiff’s pseudonym synonymous with reproductive rights. But Roe was never the bottom line on abortion, and it was never simple. The Biden 2024 campaign’s narrative about it is simple: Biden this time is running on abortion. Or more precisely, he is running on Roe.

If Joe Biden wants to run on abortion, he ought to try using the word sometimes, to start. His vice president, former prosecutor and Senator Kamala Harris, has used it more often, referring interchangeably to “Roe,” “abortion,” and “reproductive freedom”—a term with roots in activist movements, and one you will find in the opening lines of media coverage of the Biden-Harris 2024 campaign. These activist movements have long pushed the Democratic Party, mainstream reproductive rights groups, and “pro-choice” groups to expand their professed support for what was too often shorthanded as “a woman’s right to choose.” They knew for decades that Roe was in peril, in part because some of its most influential defenders failed to take on a full spectrum of political and legal issues concerning abortion, far beyond Roe. So now that Roe has been overturned, we ought to ask: When Democrats like Biden run on abortion, what precisely about abortion do they intend to defend?

The coalition of conservative and Christian-right groups that overturned Roe, of course, did not go home in 2022 content with their victory. Their next lines of attack are far from secret, and in fact have been detailed in writing. Democrats who want to defend reproductive rights should probably look to policies that would stop these strategies in their tracks. Instead, they seem to be relying on “codify Roe”—relying on the same inadequate, constrained “right” to abortion in some cases that has proven so easy to overturn, and which has now laid the groundwork for new right-wing attacks.

One of the most dangerous anti-abortion strategies the groups who campaigned for Roe’s reversal are now pursuing is a nationwide ban on all abortion. They claim that the groundwork for a national abortion ban has already been laid by the Comstock Act, passed in 1873, which in part made it illegal to mail any instrument used for performing an abortion. Despite the law’s vintage, we still live in a country in which the mail exists. As legal scholars David S. Cohen, Greer Donley, and Rachel Rebouché argue, “Because virtually everything used for an abortion—from abortion pills, to the instruments for abortion procedures, to clinic supplies—gets mailed to providers in some form, this interpretation of the Comstock Act could mean a nationwide ban on all abortions, even in states where it remains legal.” Few people have paid attention to this threat. But anti-abortion groups have, and their Comstock-as-abortion-ban arguments have won some support. As Cohen, Donley, and Rebouché point out, “federal courts in Texas and the Fifth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals have already accepted their interpretation.”

The Comstock Act has long been viewed as all but a dead letter, after decades of successive court decisions hacking away at most of it. When the act was last updated during the Clinton administration, the attorney general told Congress she would not defend or enforce its abortion-related provisions. But they remain on the books for any abortion-hostile administration to enforce. Enforcing Comstock is already part of Project 2025, a plan devised by the Heritage Foundation and dozens of other groups to enact day-one change in a coming conservative administration. “If we got Donald J. Trump back in the White House, he could end abortion in every single state in America, by enforcing the Comstock Act,” said Right to Life East Texas director Mark Lee Dickson this week.

To its credit, after Roe was overturned, the Biden administration did take some steps toward countering this potential application of the Comstock Act. In December 2022, the Department of Justice issued a memo stating its position that the Comstock Act does not prohibit mailing abortion pills. Jen Klein, director of the White House Gender Policy Council, called the Comstock Act “super dangerous” in remarks to press this week, particularly because it has a five-year statute of limitations. That means, should an abortion-hostile administration choose to do so, it could prosecute in the future any alleged violations now. Klein also noted the broader anti-abortion play—that right-wing groups “don’t think they need to pass a national abortion ban” because they think they can get courts to rule that the Comstock Act is functionally a national abortion ban.

That strategy will come before the Supreme Court this spring, in a case that will be decided before Election Day. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration is meant to block access to mifepristone, the safe and widely used abortion pill. More than half of abortions in the United States are performed using medication. Imagine what abortion access would look like in this country if the court were to side with plaintiffs, a group that did not exist until shortly before this suit was filed, incorporated in a jurisdiction so that it would end up in front of one of the most extreme right-wing judges in the federal judiciary. That judge, Matthew Kacsmaryk, has given them what they wanted: citing the Comstock Act to support the plaintiffs’ attempt to overturn the Food and Drug Administration’s 23-year-old approval of mifepristone. Further, Kacsmaryk claimed that the plaintiffs are likely to succeed in their argument that the Comstock Act already prohibits mailing mifepristone. Kacsmaryk’s order is currently stayed—and mifepristone remains available—pending the Supreme Court’s decision.

“Anti-abortion activists’ endgame was never just to overturn Roe—it was always to ban all abortions nationwide,” said Kelly Baden, vice president for Public Policy at Guttmacher, in December. “Restricting medication abortion helps them get to that goal.” They don’t need Republicans to pass a thing for this to happen. Mary Ziegler, law professor and author of Roe: The History of a National Obsession, has further argued that “the Comstock Act is the only realistic way to force through a national ban.”

Threats to abortion rights like the Comstock Act don’t fit the narrative the Biden campaign has rolled out, one in which abortion is a winning issue, as shown by multiple states passing ballot initiatives to protect abortion access. “Since Roe was overturned, every time reproductive freedom has been on the ballot, the people of America have voted for freedom,” Kamala Harris declared in Wisconsin this week.

These ballot initiatives, as successful as they have been, may be repeating some of the mistakes in Roe, by failing to affirm a much broader right to abortion. Some reproductive rights advocates want to do exactly that: establish a right to abortion that is not contingent on unnecessary or unjust restrictions, and ensure meaningful access. They want to protect the right to later abortion, specifically, and instead are faced with ballot initiatives with viability limits, like those supported by some Planned Parenthood and ACLU affiliates, as Susan Rinkunas reported at The Guardian this week. They are pushing back on the notion that it’s not strategic to seek more than Roe. As Bonyen Lee-Gilmore, vice president of communications at the National Institute for Reproductive Health, said, “There is an enormous amount of pressure being put on leaders across states to run ballots whether they are good or bad.”

As much as the Biden campaign wants to use the fear of our present post-Roe reality to turn out voters—leveraging enraging stories of abortion denied—it neglects the basic reality that Roe was never enough. Codifying Roe is not enough. You can’t run on defending Roe the way Democrats ran on defending Roe for decades, ultimately failing to keep this promise. The more these current slogans are repeated, the more it becomes clear that Joe Biden isn’t running on Roe—he’s running on “Donald Trump ended Roe v. Wade.” There is a difference.