Joe Biden’s Second-Term Agenda Is a Mystery (and That’s a Problem)

Presidential reelection campaigns are rarely dynamic or exciting. The theme is carrying on rather than change: The emphasis is on continuing work that has already begun, rather than on a broad, ambitious new agenda. There is, more generally, a sense of stasis, if not frustration: In most cases, after four years in office (if that), presidents face a divided Congress and natural roadblocks that come from the work of years of legislating. Reelection campaigns, in this vein, are typically framed around work that has been done and work that is left to be done—for Barack Obama, it was completing the recovery from the 2008 financial crash; for George W. Bush, it was keeping America “safe” from the threat of terrorism (by fighting unrelated foreign wars); for Bill Clinton, it was keeping the economy humming. Reelection campaign slogans often reflect a palpable sense of exhaustion. Donald Trump’s was a light edit to his first campaign slogan—he went with “Keep America Great.” Obama’s was simply “Forward”—which was perilously close to one adopted and quickly discarded by his immediate predecessor (“Moving America Forward”). Forward to where? It wasn’t entirely clear. (Bill Clinton’s helpfully noted that he would be “Building a Bridge to the 21st Century,” even though that would be coming with or without his help.) In any case, a theme is clear: Reelection campaigns revolve around protecting progress that has already been made—and, maybe, if everyone is lucky, building a bit upon it. Joe Biden’s reelection campaign is in trouble for many reasons. Some are existential: Voters think that the 81-year-old president is too old now and that he certainly will be when he ends a hypothetical second term as an 86-year-old. His vice president, Kamala Harris, is arguably even more unpopular than he is, and he is historically unpopular—only 40 percent of voters approve of his presidency, per RealClearPolitics’s aggregate polling, and he is trailing Trump both nationally and in most of the six swing states that will likely decide the election. Others are more circumstantial: Voters do not like the economy or the state of the world, and they blame Biden. One hope among the president’s allies is that, as the election nears and a sharper contrast is drawn between Trump and Biden, events will shift in the current president’s favor: that voters will stop griping about price rises, appreciate the low unemployment rate, high wages, and the administration’s efforts to combat inflation without triggering a recession, and that there will be successful efforts to resolve the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza. They may, at the very least, recognize that Donald Trump’s involvement would have made inflation and the ongoing global conflicts significantly worse. This is optimistic but untested. Biden has an additional problem: Voters see the bad stuff (inflation, foreign wars) but not much good stuff (infrastructure spending, the successful effort to rein in inflation). This makes running a traditional reelection campaign daunting: Why carry on with an economy and a foreign policy that no one really likes? Biden’s reelection campaign has yet to kick into gear, but the time for laying out a second-term agenda—a real one, not the milquetoast “keep on trucking” appeal favored by most of his predecessors—is here. Thus far, it’s not entirely clear what a Biden second term would look like, a problem that exacerbates many of the president’s other ones: There is a palpable sense of inertia within the administration. Biden could jump-start his flagging campaign by returning to the ambitious agenda he pursued in the first two years of his administration: pushing large-scale spending programs that helped lower unemployment and raise wages. He can continue to promote the pro-union agenda that he has, with some success, deployed during the strike wave that defined much of the middle portion of 2023. Unlike the campaign’s current focus—“Bidenomics,” an attempt to sell voters on an economy they simply do not like—the president’s campaign can push the idea that further large-scale programs are the way out: They’ll raise wages and help ease the burden of high prices. On domestic policy, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that Biden and his allies have yet to play their trump card. Voters have, across the country, repeatedly voiced their displeasure at the repeal of Roe v. Wade. There is every indication that they will continue to do so and that abortion will be the most important issue for a significant number of voters—it will likely be the most important noneconomic issue in the presidential election. Biden is helped by the fact that the repeal would not have happened had Trump not appointed three very conservative justices to the Supreme Court. Biden can run on protecting a woman’s right to choose—and on appointing liberals to the Supreme Court, should vacancies arise. (The two oldest members of the court are both conservatives who can be expect

Presidential reelection campaigns are rarely dynamic or exciting. The theme is carrying on rather than change: The emphasis is on continuing work that has already begun, rather than on a broad, ambitious new agenda.

There is, more generally, a sense of stasis, if not frustration: In most cases, after four years in office (if that), presidents face a divided Congress and natural roadblocks that come from the work of years of legislating. Reelection campaigns, in this vein, are typically framed around work that has been done and work that is left to be done—for Barack Obama, it was completing the recovery from the 2008 financial crash; for George W. Bush, it was keeping America “safe” from the threat of terrorism (by fighting unrelated foreign wars); for Bill Clinton, it was keeping the economy humming.

Reelection campaign slogans often reflect a palpable sense of exhaustion. Donald Trump’s was a light edit to his first campaign slogan—he went with “Keep America Great.” Obama’s was simply “Forward”—which was perilously close to one adopted and quickly discarded by his immediate predecessor (“Moving America Forward”). Forward to where? It wasn’t entirely clear. (Bill Clinton’s helpfully noted that he would be “Building a Bridge to the 21st Century,” even though that would be coming with or without his help.) In any case, a theme is clear: Reelection campaigns revolve around protecting progress that has already been made—and, maybe, if everyone is lucky, building a bit upon it.

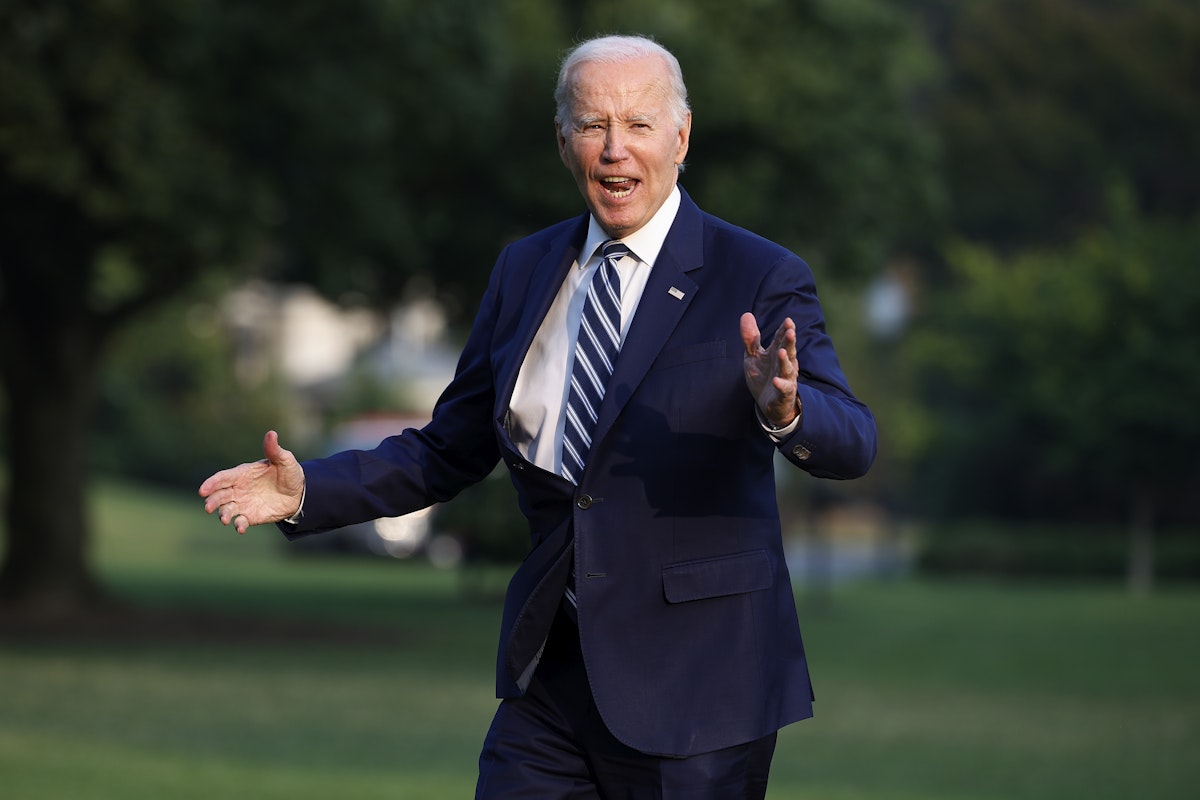

Joe Biden’s reelection campaign is in trouble for many reasons. Some are existential: Voters think that the 81-year-old president is too old now and that he certainly will be when he ends a hypothetical second term as an 86-year-old. His vice president, Kamala Harris, is arguably even more unpopular than he is, and he is historically unpopular—only 40 percent of voters approve of his presidency, per RealClearPolitics’s aggregate polling, and he is trailing Trump both nationally and in most of the six swing states that will likely decide the election. Others are more circumstantial: Voters do not like the economy or the state of the world, and they blame Biden.

One hope among the president’s allies is that, as the election nears and a sharper contrast is drawn between Trump and Biden, events will shift in the current president’s favor: that voters will stop griping about price rises, appreciate the low unemployment rate, high wages, and the administration’s efforts to combat inflation without triggering a recession, and that there will be successful efforts to resolve the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza. They may, at the very least, recognize that Donald Trump’s involvement would have made inflation and the ongoing global conflicts significantly worse.

This is optimistic but untested. Biden has an additional problem: Voters see the bad stuff (inflation, foreign wars) but not much good stuff (infrastructure spending, the successful effort to rein in inflation). This makes running a traditional reelection campaign daunting: Why carry on with an economy and a foreign policy that no one really likes?

Biden’s reelection campaign has yet to kick into gear, but the time for laying out a second-term agenda—a real one, not the milquetoast “keep on trucking” appeal favored by most of his predecessors—is here. Thus far, it’s not entirely clear what a Biden second term would look like, a problem that exacerbates many of the president’s other ones: There is a palpable sense of inertia within the administration.

Biden could jump-start his flagging campaign by returning to the ambitious agenda he pursued in the first two years of his administration: pushing large-scale spending programs that helped lower unemployment and raise wages. He can continue to promote the pro-union agenda that he has, with some success, deployed during the strike wave that defined much of the middle portion of 2023. Unlike the campaign’s current focus—“Bidenomics,” an attempt to sell voters on an economy they simply do not like—the president’s campaign can push the idea that further large-scale programs are the way out: They’ll raise wages and help ease the burden of high prices.

On domestic policy, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that Biden and his allies have yet to play their trump card. Voters have, across the country, repeatedly voiced their displeasure at the repeal of Roe v. Wade. There is every indication that they will continue to do so and that abortion will be the most important issue for a significant number of voters—it will likely be the most important noneconomic issue in the presidential election. Biden is helped by the fact that the repeal would not have happened had Trump not appointed three very conservative justices to the Supreme Court. Biden can run on protecting a woman’s right to choose—and on appointing liberals to the Supreme Court, should vacancies arise. (The two oldest members of the court are both conservatives who can be expected to retire if Trump wins reelection.)

On immigration, Biden faces a different problem, especially as he has adopted more and more of his predecessor’s vile, draconian policies in an effort to deflect criticism. Nonetheless, Biden can (and should) propose a more cohesive framework for actual immigration reform—and use it as a contrast with Trump, whose policies are purely fascistic. In terms of foreign policy, things are similarly complex. Nevertheless, the Biden administration’s current approach—continuing to fund, to the tune of billions, two ongoing wars with no clear endgame or off-ramp—is a failure. But Biden can begin to articulate how these wars can end—while making the case that Trump’s own approach (a Nixonian “secret plan”) is a fantasy.

It is true, of course, that most of these policies are unlikely to come to fruition, should Biden win reelection—Democrats may retake the House, but they will be lucky to hold onto a slim majority in the Senate; in any case, as the first two years of his term showed, getting things done when you have slim majorities is hard, whether you be a Democrat or a Republican. But that also doesn’t matter! Political campaigns are about visions and contrast, not the petty realities of governing in a country with a constitutional system that makes achieving anything quite difficult. Biden is shirking his biggest responsibility right now, which is to make a cohesive and comprehensive case for why he should be reelected. The answer is not that he’s an octogenarian who will keep a stalled ship running. Instead, it’s time to articulate a vision for the country in 2025—and beyond.