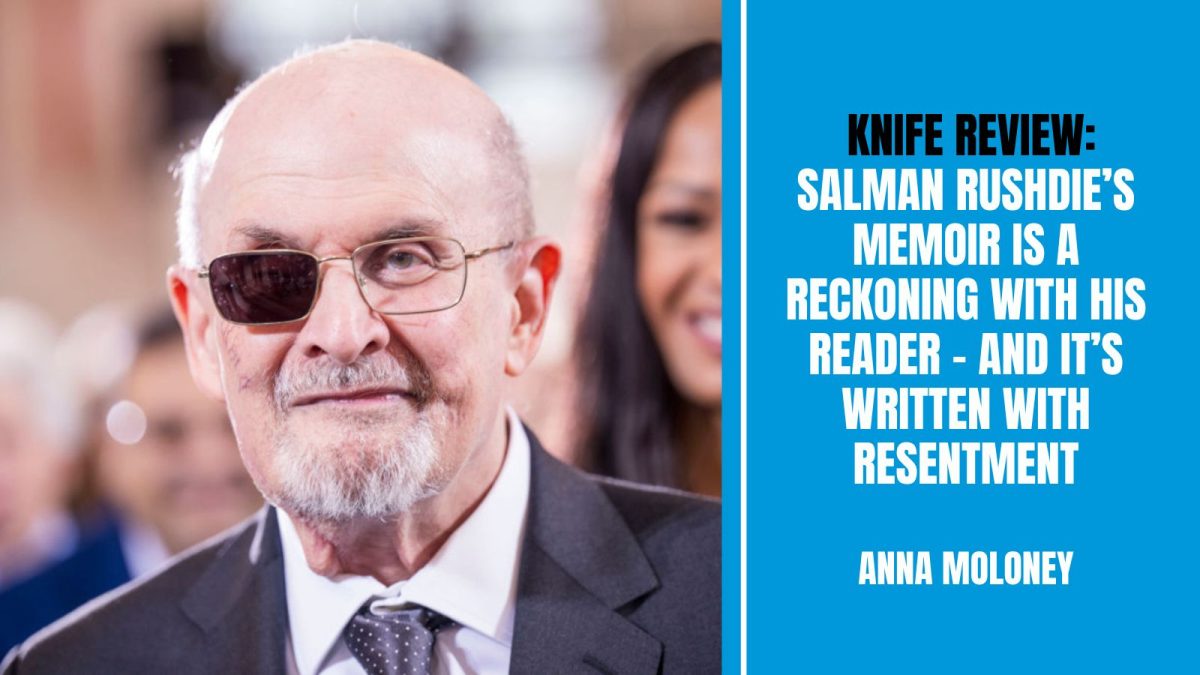

Knife review: Salman Rushdie’s memoir is a reckoning with his reader – and it’s written with resentment

Salman Rushdie's Knife is a reckoning with his reader, and it is written with resentment, writes Anna Moloney.

Knife is a moving memoir, but Salman Rushdie’s yearning to separate life from art is riddled with contradiction, writes Anna Moloney

“The knife defines me,” Salman Rushdie writes. He wishes it didn’t. As such, Knife is not just a reckoning with the violent attack that nearly took his life just a little over a year and half ago, it’s also a reckoning with what it changes about him as a writer – or more to his point, us as readers.

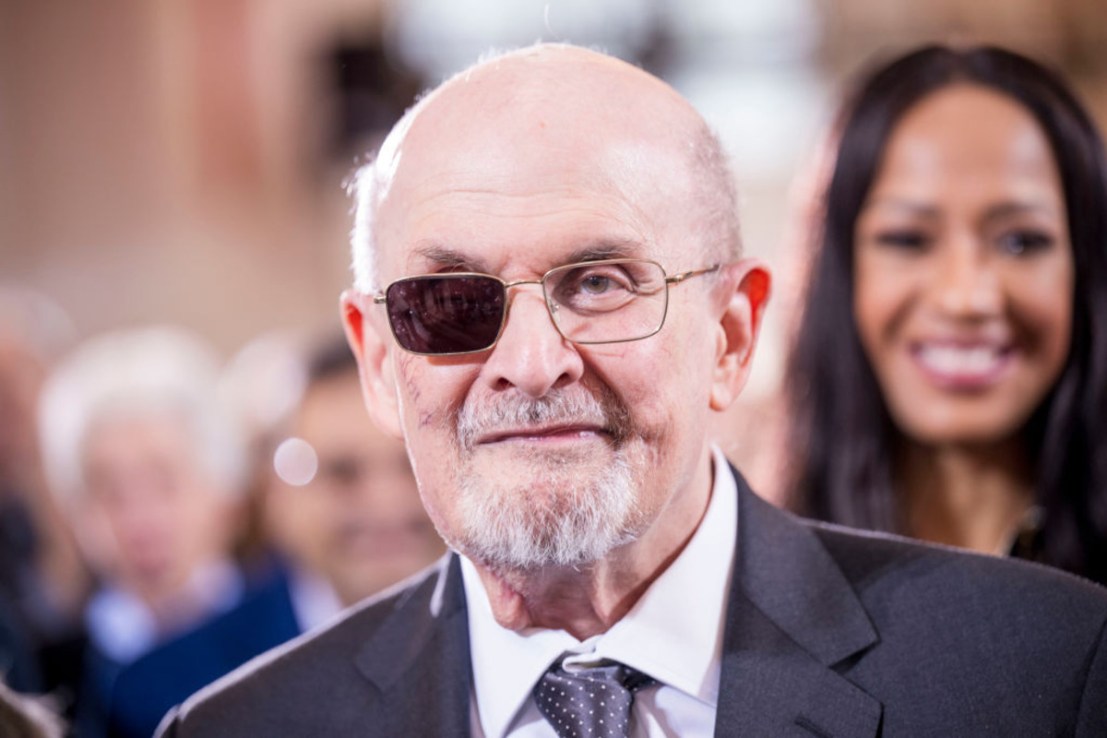

Rushdie was stabbed 15 times in 27 seconds in August 2022. He had been about to deliver a lecture in Chautauqua, New York, when his assailant (referred to only as ‘the A’) rushed onto the stage. The incident left him in a critical condition, and with permanent scars. His eye hung on his cheek “like a soft-boiled egg” and it took months of therapy to be able to move his hand again. That he survived, the self-confessedly “godless” Rushdie writes, was a miracle.

Despite Rushdie’s reluctance to equate writing to therapy – “writing is writing, and therapy is therapy” – Knife is without doubt an exercise of healing for the writer. At an event talking about the book yesterday, the writer said it was the only book he had ever written with the help of a therapist and had helped him regain “control of the narrative”. His fifth wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, is also presented as a driving force in his recovery. Rushdie describes his romance with Eliza in treacly detail, either sweet or nauseating depending on your point of view. The ending, in which Rushdie takes Eliza’s hand and declares “let’s go home” strays towards the latter.

Rushdie’s medical recovery, in contrast, is written with near visceral succinctness. The passages describing his physical recovery are often gruesome and leave the reader with no misconceptions about the magnitude of the attack, although there are also moments of humour. In a revealing moment, as his clothes are cut away from him on the stage to uncover his wounds, Rushdie remembers thinking “not my nice Ralph Lauren suit!”, while fussing about his keys and cards in his pocket. A lighthearted detail, but one, he reflects, spoke to that human insistence to live. That he should have died, considering the nature of the attack, is made clear.

Hadi Matar, who is still awaiting trial for the attack, said he was surprised the writer survived. Rusdhie’s writing about ‘the A’ is surprisingly sardonic. He quips that Matar – who after the stabbing admitted he had only read a “couple of pages” of Rushdie’s work but found the writer “disingenuous” – would have been rejected as an “unconvincing” character by his editors had he submitted it in a novel. Rushdie uses Knife to confront his assailant through a fictional imagining of an interview in which he throws jibes at Matar about being a virgin and his rudimentary understanding of philosophy. Rushdie claims his assailant is “simply irrelevant” to him, but, written within a whole chapter dedicated to “the A”, it is hard to know whether we are meant to believe this. Rushdie later recalls going to visit the prison holding Matar and feeling “foolishly happy” as he stood outside it. “[I] wanted, absurdly, to dance,” he admits.

The greatest damage inflicted on Rushdie, the writer claims, both before and because of the attack, is the way his story has been stolen. “I’ve become a strange fish, famous not so much for my books as for the mishaps of my life.” And indeed the reception received so far by Knife – largely glowing – in a way speaks to Rushdie’s point. Where the British media once found him arrogant and egotistical, or alternately an incessant womaniser, it now finds him ‘good’: the sympathetic near-martyr, “liberty-loving Barbie doll, Free Expression Rushdie”, he quips. He as a writer, however, he asserts, is unchanged by the events.

Indeed any suggestion that the attack, or the fatwa long before, has affected his writing elicits a defensive reaction from Rushdie, who appears resentful that he must write this story. The act of violence, the writer asserts, has nothing to contribute to art. “It will affect the way my writing is read. Or not read. Or both.” Shame on the reader then.

This is an affecting notion, but it rings a little hollow within a memoir written explicitly to reckon with the event. The need to document the incident, Rushdie admits, was his first coherent thought after the attack. The attack was not just the elephant in the room, but a “fucking enormous mastodon” in his office. Until he had dealt with it, he wouldn’t be able to write about anything else.

Readings of Rushdie’s writing, including that written before the attack, will now undoubtedly be coloured by this event. Though Knife is the first book written by Rushdie since the attack, it’s the second that’s been published, with Victory City (Rushdie’s 15th novel) released last February. That the proofs were signed off before the attack is something which seems incredible if you read Victory City, a book in which blindness and prophecy figure as two major themes.

Written about an ancient city grown from a bag of seeds, Victory City centres on prophet and poet Pampa Kampana – who is brutally blinded but determined to finish writing the story of her city. Writing through her blindness is painful but she persists. “She began to feel her selfhood returning as she wrote. She wrote slowly, much more slowly than in the past, but the writing was neat and clear”. In Knife, Rushdie writes about the physical pain of writing “with one eye and one a half hands… its awkwardness reminds you at every stroke of the keyboard of the cause of your pain”.

In what is one of the most moving confessions in Knife, Rushdie writes how blindness had always been his ultimate fear; his room 101. Coming to terms with his lost sight since the attack has therefore been one of the most challenging parts of his recovery, an insight which makes Victory City all the more affecting.

Pampa’s fate at the end of the novel is left ambiguous, as she finishes writing her story and then waits for the goddess to release her from this life, but Rushdie speculates on a fantastical ending for her, one where she is “led through the celestial gates into the Eternal Fields, where she was no longer blind” – a fantasy now perhaps with added weight.

But Pampa’s own last words are not a yearning for sight as the prophet, but a declaration of triumph as a poet. “I myself am nothing now. All that remains is this city of words. Words are the only victors.” And Rushdie, too, is keenly aware of his own mortality, and how he will be outlived by his work. When he first regained consciousness after the attack, he writes of recalling visions of “majestic palaces and other grand edifices that were all built out of alphabets”. In other words, he too dreamed of cities of words.

Knife is a moving tale with moments of powerful writing, but its heart is struck with contradiction. Rushdie says he wishes not to be remembered for the story of his life, but for his storytelling; but Knife, by its very existence, shows that life and art cannot be easily separated. And I’m not sure what we would gain if we could.

Rushdie may regret that the reading of his work is coloured by his life story, but to ignore it, you might say, would be like ignoring a fucking enormous mastodon in the room.