Kursk Oblast: Where Russia’s “historical lands” argument falls apart

As Ukrainian troops advance into Kursk Oblast, they encounter an unexpected ally: history itself. Ironically, Russia's justification for invading Ukraine crumbles on its own soil.

The Kremlin has long justified its territorial ambitions by invoking the need to reclaim “historical lands.” This rhetoric reached a fever pitch before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when Russian President Vladimir Putin penned a lengthy treatise on Ukrainian history—as he perceived it. In this document, Putin asserted that parts of Ukraine rightfully belonged to Russia and went so far as to deny the very existence of a distinct Ukrainian nation. He reiterated these arguments in a history-laden speech on 23 February 2022, attempting to legitimize the impending invasion.

However, the events unfolding in Kursk Oblast, a region in western Russia, starkly illustrate the flaws in this narrative. When Ukrainian troops advanced into the area on 6 August 2024, they were greeted by many locals speaking Ukrainian—a poignant reminder of the region’s Ukrainian heritage. This ironic turn of events underscores the fallacy of Russia’s oversimplified claims about historical ownership.

Indeed, contrary to Putin’s assertions, a Russian population never dominated any of the contemporary Ukrainian regions. Moreover, Putin’s historical argument has backfired spectacularly.

At the same time, historical claims alone cannot dictate geopolitics. Forceful border changes could lead to endless conflict and Ukrainian officials have made it clear that Ukraine does not seek to alter internationally recognized borders or claim Russian territory.

Nevertheless, Ukrainian military operations will continue on Russian soil to disrupt Russia’s capacity to wage war until Russia is ready to negotiate a “just peace,” which must include the restoration of Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders as they were before 2014.

Parts of Russia’s southwest were predominantly Ukrainian until the 1932-1933 genocide

In August 2024, Ukrainian forces occupied Sudzha, a town where Ukrainians constituted 61% of the population in 1897, according to the Russian Empire’s census. This demographic makeup was not unique to Sudzha; many districts in contemporary Russia had a Ukrainian majority a century ago.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, portions of present-day Russia—specifically, southwestern Kursk and Belgorod oblasts, and southern Voronezh Oblast—belonged to Ukraine’s Sumy, Okhtyrka, Kharkiv, and Ostrohozk regiments (polks). These polks, administrative units within Ukraine’s Cossack State, were led by elected commanders called polkovnyks, who wielded both military and civilian authority.

In the late 17th century, eastern Ukrainian polks enjoyed considerable autonomy within the Russian Empire, which balanced between controlling Ukrainian people and utilizing their strength as an effective military force on the southern border. However, this autonomy eroded after Ukrainians allied with Sweden in the Great Northern War and were defeated. By 1768, Ukrainian lands had fallen under full Tsarist control, losing their autonomy.

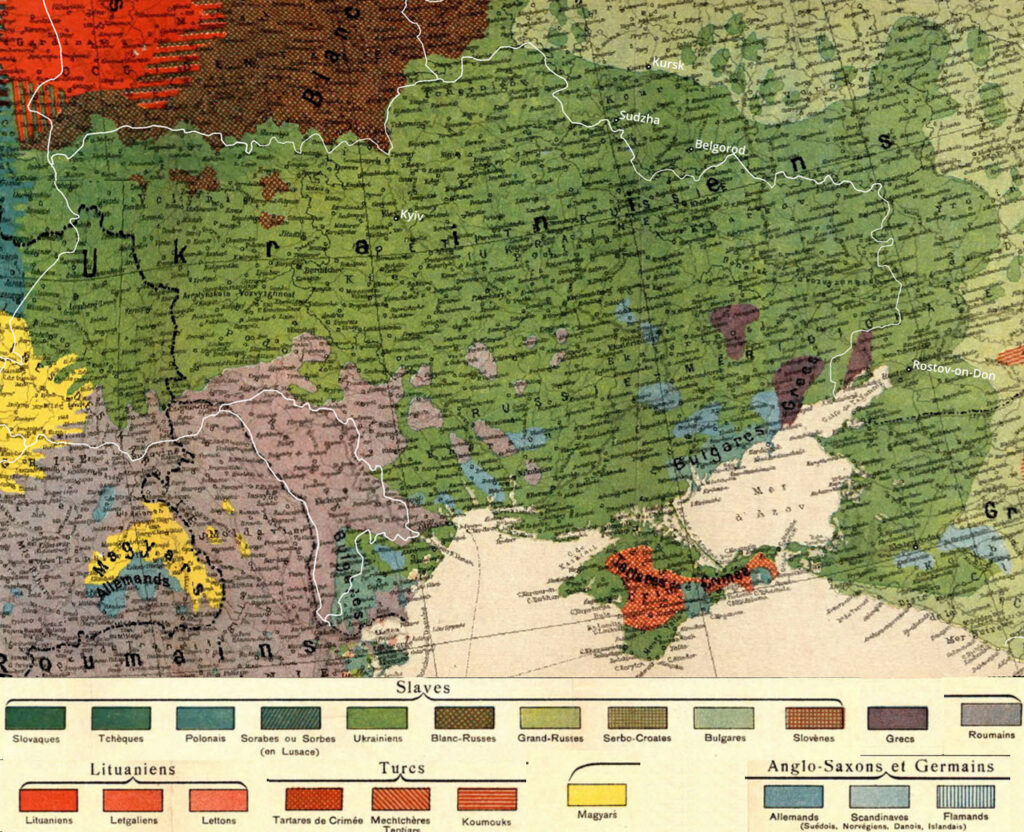

Despite this, throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these parts of contemporary Russia maintained a significant Ukrainian presence.The 1897 Russian census, along with 61% in the town of Sudzha, Ukrainians were widely present in other towns: 51% in Ostrohozk, 43% in Hrayvoron, 82% in Biryuch, and similar numbers in the surrounding rural areas. Historical maps, including those from the early 20th century, depict these areas as part of a Ukrainian ethnic territory defined by the language spoken.

The maps include the 1915 “Overview Map of Ukrainian Lands” by Ukrainian Georgrapher Stepan Rudnytskyi, the 1912 “Ethnographic Map of Slavic Lands” by Czech archeologist, anthropologist and ethnographer Lubor Niederle, the 1918 Swiss Ethnographic Map of Europe, and many more.

The opposite situation — where some territories within present-day Ukraine were historically more populated by Russians than Ukrainians — did not occur.

The only areas that were not predominantly Ukrainian were central Crimea, southern Odesa Oblast, Zakarpattia Oblast, and south Chernivtsi Oblast. where Ukrainians were the second-largest ethnic group. However, Russians were not the dominant group in these Ukrainian regions. Depending on the district, Bulgarians, Romanians, Crimean Tatars, Hungarians, Romanians, or German colonists formed the largest ethnic groups.

Early 20th-century Ukrainian geographers and sociologists—Stepan Rudnytsky, Mykyta Shapoval, and Volodymyr Kubiyovych—estimated the Ukrainian ethnic territory between 728,500 km² and 905,000 km², based on censuses and ethnographical data. The lower estimate included only territories with a strong Ukrainian majority.

For context, Ukraine’s internationally recognized borders encompass 603,700 km², suggesting that Ukraine, rather than Russia, could potentially claim the return of “historical lands.”

The extent of the ethnic cleansing of Ukrainians

A dramatic demographic shift occurred in 1932-1933. Previous Russian and Soviet attempts to assimilate Ukrainian identity into Russian had yielded only limited results. However, Stalin’s genocide by starvation, known as the Holodomor, struck southeastern Ukraine with particular ferocity, including Ukrainian lands now part of Russia.

Soviet authorities and collective farms forcibly confiscated all food and livestock, selling it abroad while imposing border restrictions. This engineered famine resulted in an estimated 4 million deaths during 1932-1933.

The 1926 USSR census recorded 23 million Ukrainians in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, with an additional 7.8 million in the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic. For context, only 2.3 million Russians lived in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic at that time, indicating that official borders between Ukraine and Russia favored Russian territorial claims over Ukrainian ones.

In the aftermath of the 1932-1933 genocide, the 1939 census revealed a stark decline in the Ukrainian population. The total number of Ukrainians in the Soviet Union had decreased from 31.2 million to 28.1 million. Conversely, the Russian population surged from 77.8 million to 99.9 million during the same period. Ukrainians and Kazakhs were the only nationalities to suffer such a precipitous population decline, while other nationalities in the USSR grew more or less in proportion to the overall population increase from 147 million to 170.6 million.

Comparing maps of the highest Holodomor casualties with pre-Holodomor ethnic distributions explains the subsequent rapid increase in Russian numbers and decrease in Ukrainian population in these “cleansed” lands. The USSR’s ensuing policy of Russification further suppressed the remaining Ukrainian populace.

The lost identity of Ukrainians in Russia revealed by Ukraine’s Kursk offensive

Unlike those in Ukraine, who experienced a revival of Ukrainian culture and identity after 1991, the remaining Ukrainians in Russia lacked this opportunity. They gradually lost their identity and national memory over generations. According to Russian censuses conducted after 2000, the proportion of people identifying as Ukrainians in formerly Ukrainian-populated areas dwindled to a mere few percent.

Many who began identifying as “Russian” in censuses still retained a vestige of local identity, though often without recognizing or acknowledging its Ukrainian roots. This identity was frequently maintained in a provincial manner. A striking example of the consequences of Soviet genocide and Russification policy was displayed on a contemporary Russian TV show, featuring a young woman from Kozynka village in the Hrayvoron district of Belgorod Oblast.

The woman shared local recipes with the TV hosts and, at one point, began speaking “in our local dialect” to demonstrate it. The hosts struggled to understand, commenting that the words of this “unique dialect can’t be found in any dictionary in the world.”

Neither the hosts nor the young woman seemed to realize she was speaking the same language millions of Ukrainians use just across the border. Moreover, the local customs she described resembled Ukrainian rather than Russian ethnic culture, yet this connection went unrecognized by both the hosts and their guest.

This remarkable instance not only reveals that remnants of Ukrainian culture persist in these Russian areas but also underscores the extent of historical amnesia and cultural destruction local Ukrainians have endured under Soviet and Russian state control.

It’s difficult to predict whether these people would ever identify as Ukrainian again, especially younger generations, even if Russia were to become democratic and allow self-determination. The Ukrainian population in these areas suffered significant losses, and Russian propaganda has long worked to assimilate the remainder.

Nevertheless, when Ukrainian troops entered Sudzha and surrounding villages in Russia’s Kursk Oblast, many elderly locals spoke Ukrainian to the soldiers. Overall, there was no civil resistance to the Ukrainian army, and numerous videos published by soldiers showed positive or at least neutral attitudes toward the Ukrainian forces.

As an example, an elderly woman, speaking Ukrainian, told a Ukrainian soldier that authorities had abandoned her village near Sudzha, while her son used to come from Sudzha to bring her food: