Natural Gas Is Way Worse Than Coal

Natural gas may be worse for the world than coal, but it’s got two important things on its side: the word natural and the seemingly unconditional support of the United States government. Preliminary research by Cornell University’s Robert Howarth, reported in The New Yorker by Bill McKibben this week, finds that “natural” (methane) gas may be 24 percent worse for the climate than coal in the best-case scenario. That’s thanks to extensive methane leaks at just about every stage of its production, from drilling to transportation. In the worst-case scenario—when LNG makes long journeys on old, polluting tankards—the fuel is 274 percent worse for the environment than coal is.So why is the Biden administration enthusiastically trying to expand methane exports? Last spring, the administration greenlit a $39 billion project to export gas from Alaska. The U.S. is the largest gas exporter in the world, having only gotten into the business in 2016. Last month, McKibben notes, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved a fracked-gas pipeline in the Pacific Northwest and an expansion of a Venture Global facility known as Calcasieu Pass. Not factoring in Howarth’s math, emissions from “CP2” were already expected to be 20 times greater than those given off by the controversial Willow Project in Alaska. Both the industry and the administration have argued that such projects are necessary to provide energy security to “our European allies,” who have been attempting to wean themselves off gas from Russia since it invaded Ukraine last year. As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has found, though, Europe’s spending binge on gas-import facilities is outpacing demand. This all seems a bit incongruous with the administration’s other professed goals, like keeping the world from warming by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). Maybe the problem is a lack of object permanence: If gas is shipped abroad, we don’t need to worry about its emissions. Another explanation, if one considers national security adviser Jake Sullivan’s recent essay for Foreign Policy, is a bit darker. Sullivan paints a bleak picture of a country beset by competition with its geopolitical rivals. Adjusting to the “new realities of power,” he writes, means recognizing that “international power depends on a strong domestic economy.”“It is absolutely necessary if the United States is to win the competition to shape the future of the international order so that it is free, open, prosperous, and secure,” Sullivan argues. The bipartisan infrastructure bill, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act—aimed at bolstering strong, strategic export industries and lessening “dangerous dependencies”—serve to position the U.S. “to better absorb attempts by external powers to limit American access to critical inputs.”It’s important to take what White House officials like Sullivan say seriously. Sullivan acknowledges that climate change is important. But he seems to think that solving it will depend on America’s ability to shape the world order in its own image. The upshot of this kind of climate policy—a climate policy motivated chiefly by geopolitical anxieties—is that it isn’t really climate policy, whose chief goal should be reducing emissions. Looking to bolster domestic supply chains for clean energy is a perfectly fine goal. But if the ultimate prize is preserving the U.S. as a de facto super power, there’s no reason why expanding clean energy would need to be mutually exclusive with ever-expanding fossil fuel exports. If the Biden administration really wants to plan for decarbonization, that would entail a very different approach—one that treats LNG and the ever-worsening picture of its emissions as something other than a “source of strength.”

Natural gas may be worse for the world than coal, but it’s got two important things on its side: the word natural and the seemingly unconditional support of the United States government. Preliminary research by Cornell University’s Robert Howarth, reported in The New Yorker by Bill McKibben this week, finds that “natural” (methane) gas may be 24 percent worse for the climate than coal in the best-case scenario. That’s thanks to extensive methane leaks at just about every stage of its production, from drilling to transportation. In the worst-case scenario—when LNG makes long journeys on old, polluting tankards—the fuel is 274 percent worse for the environment than coal is.

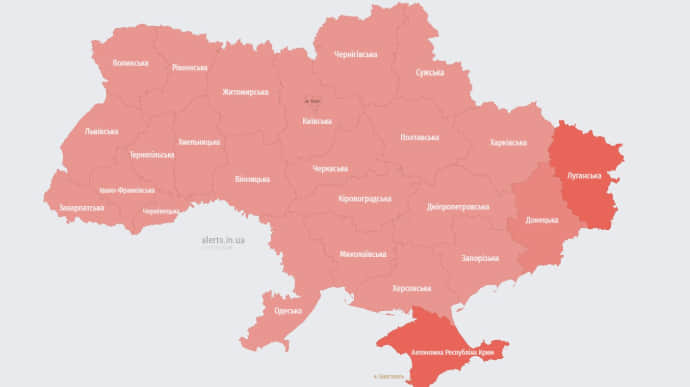

So why is the Biden administration enthusiastically trying to expand methane exports? Last spring, the administration greenlit a $39 billion project to export gas from Alaska. The U.S. is the largest gas exporter in the world, having only gotten into the business in 2016. Last month, McKibben notes, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved a fracked-gas pipeline in the Pacific Northwest and an expansion of a Venture Global facility known as Calcasieu Pass. Not factoring in Howarth’s math, emissions from “CP2” were already expected to be 20 times greater than those given off by the controversial Willow Project in Alaska. Both the industry and the administration have argued that such projects are necessary to provide energy security to “our European allies,” who have been attempting to wean themselves off gas from Russia since it invaded Ukraine last year. As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has found, though, Europe’s spending binge on gas-import facilities is outpacing demand.

This all seems a bit incongruous with the administration’s other professed goals, like keeping the world from warming by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). Maybe the problem is a lack of object permanence: If gas is shipped abroad, we don’t need to worry about its emissions. Another explanation, if one considers national security adviser Jake Sullivan’s recent essay for Foreign Policy, is a bit darker. Sullivan paints a bleak picture of a country beset by competition with its geopolitical rivals. Adjusting to the “new realities of power,” he writes, means recognizing that “international power depends on a strong domestic economy.”

“It is absolutely necessary if the United States is to win the competition to shape the future of the international order so that it is free, open, prosperous, and secure,” Sullivan argues. The bipartisan infrastructure bill, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act—aimed at bolstering strong, strategic export industries and lessening “dangerous dependencies”—serve to position the U.S. “to better absorb attempts by external powers to limit American access to critical inputs.”

It’s important to take what White House officials like Sullivan say seriously. Sullivan acknowledges that climate change is important. But he seems to think that solving it will depend on America’s ability to shape the world order in its own image.

The upshot of this kind of climate policy—a climate policy motivated chiefly by geopolitical anxieties—is that it isn’t really climate policy, whose chief goal should be reducing emissions. Looking to bolster domestic supply chains for clean energy is a perfectly fine goal. But if the ultimate prize is preserving the U.S. as a de facto super power, there’s no reason why expanding clean energy would need to be mutually exclusive with ever-expanding fossil fuel exports. If the Biden administration really wants to plan for decarbonization, that would entail a very different approach—one that treats LNG and the ever-worsening picture of its emissions as something other than a “source of strength.”