Oil majors recap: How is 2024 treating Shell, BP, Exxon and Chevron?

Exxon's 2023 profits were down 35 per cent but still the second highest in a decade.

For the big four of oil and gas, the first three months of 2024 have largely been taken up with stock-takes from the previous year.

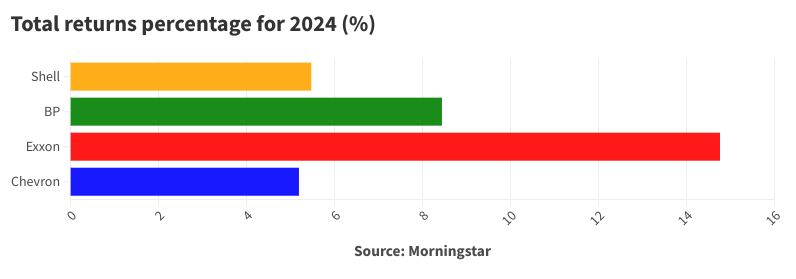

Full-year results season for UK supermajors BP and Shell, as well as US giants Exxon and Chevron, did not bring the riches of 2023.

All suffered double-digit return falls at the hands of more stabilised oil prices, but investors were kept satiated through the promise of hefty buyback programmes.

Exxon: The unassailable king

Despite the climb-down from 2022, Exxon’s 2023 ranked the strongest.

The oil behemoth led its peers across the board, with $36bn (£28.5bn) in earnings during 2023, $55bn (£43.5bn) in cash flow from operations and a total of $17.5bn (£13.8bn) of buybacks last year.

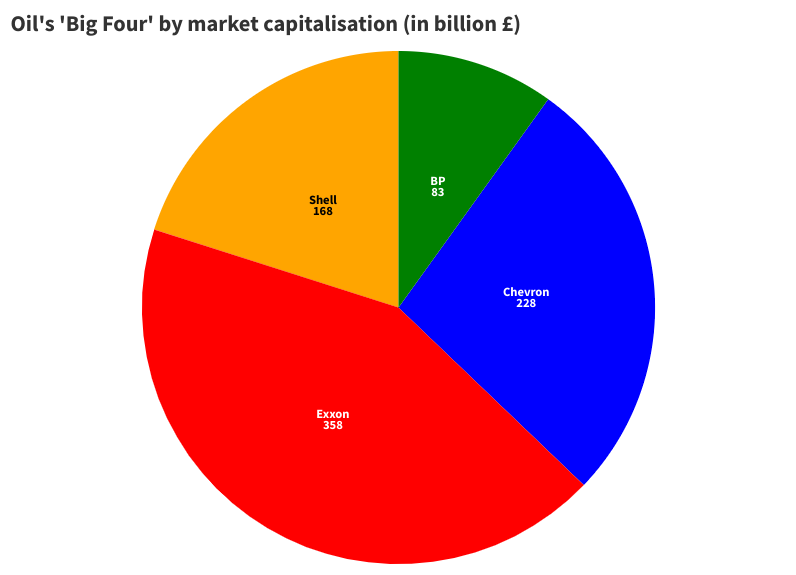

It remains the unassailable king of the peer group as the world’s largest investor-owned oil company and shows little sign of giving up its crown anytime soon.

The group plans to go steady on an expected, yet modest, demand in the rise for crude oil in 2024, forecasting a less-than-2 per cent production increase for the year.

This would result in an average net production of about 3.8m barrels of oil equivalent per day (mboe/d) in 2024, versus 3.74mboe/d in 2023.

And while the world is caught up on 2030 net zero targets, Exxon has a milestone for that year of its own that it is already beginning to work towards.

The firm is ahead of schedule with its plan to double the size of its liquefied natural gas LNG portfolio to 40m tons per year (mtpa) by 2030.

This wouldn’t put it on par with rivals and LNG-leader Shell in terms of size, but the group sees the potential to succeed through other metrics.

“We want to have the leading LNG portfolio in the world in terms of its financial robustness and financial returns and I would say we’re well on the way to doing it,” the company’s senior vice president for global LNG, Peter Clarke said last week.

Additionally, Exxon is due a big windfall in 2024 when its $64bn (£50.6bn) splash on Pioneer Natural Resources, announced at the tail end of last year, completes in a few months time.

It’s estimated that the move will likely more than double the company’s Permian Basin footprint.

Chevron: America’s little brother

Chevron is playing little brother in the US fossil fuel game, but playing it well.

The firm was beaten into third place for 2023 earnings by Exxon and Shell, returning $21.4bn (£16.9bn), a 39 per cent slide on the previous year.

Part of its plan to climb the petrogiant leader board is to go hard on oil and gas spending, with an $18.5-19.5bn (£14.6-15.4bn) tranche for this financial year alone.

In context, this is more than the $14-18bn (£11-14bn) BP has scoped to spend annually on its building its entire energy portfolio between now and 2030.

Chevron is also waiting on a windfall of its own from the pending $53bn (£41.9bn) buy of Hess at the end of last year, a move that boosts its US and Guyana footprints.

Shell: Easy does it

Shell meanwhile, through its chief executive Wael Sawan, has been clear to its shareholders and the public that it will invest prudently and scrupulously in projects that return value to investors.

The firm recently caught some flak when it revealed that it was dropping a 2035 emissions target to reduce carbon intensity of its products by 45 per cent due to “uncertainty in the pace of the energy transition”.

The group also added the equivalent of 200,000 barrels of oil and gas production to its target output, and it plans to start enough new fossil fuel projects to add half a million barrels a day to its oil and gas production by 2025.

BP: A crisis of identity

BP has a lingering identity issue it’s struggling to shake off, amidst reports of growing investor disquiet over proposals to expand its clean energy portfolio.

The company has struggled to keep within remote touching distance of Shell in recent years.

Former chief executive Bernard Looney laid the groundwork for a future BP that embraced the energy transition, a move that his successor Murray Auchincloss seems to have partially retained.

But there is reportedly a groundswell of investor ire at BP’s pursuit of this strategy, one that activist investor Bluebell has been and is continuing to try and stoke further.

A greener future for Big Oil?

In an ironic twist, it was the petrostate of Dubai and its COP 28 summit held last year that seems to have instigated a feeling globally to energy transition moving.

And while the energy industry still largely feels like an echo chamber, more of the shouting seems to be leaking out into the worlds of big business and politics.

But for as long as big oil is seen to be investing in clean energy, to whatever extent, its conscience is clear.

Fossil fuel profits will keep coming for the foreseeable future, in part because their largest operators say they cannot profitably perform an instant pivot to renewable energy projects.

“Roll the clock back four or five years ago, they were like: ‘Oh, it’s all going to be renewables and batteries’ — and now they’re saying: ‘Wow, wow, this is going to be way too expensive,” Alan Armstrong, head of the US’ largest gas pipeline company, Williams, told the Financial Times last week.

Shell’s Sawan has echoed this sentiment saying that until low carbon initiatives become “commercially available,” it will continue to invest in oil and gas, but with lower emissions.

Exxon’s chief Darren Woods went one further earlier this month, telling Fortune Magazine that the high cost of clean energy transition is the “dirty secret” that the public cannot or will not accept.

For investors, particularly of Shell, Exxon and Chevron, the sentiment is likely welcome news, for now at least.

Each is pretty set on their respective courses for this year; maximise profitability, diversify where possible, make it clear that renewable energy projects are risk-ridden.

The public’s ‘they are not doing enough’ charge as it pertains to the big four’s green priorities tends to spike four times a year, coinciding with results reporting milestones.

But this year, with November’s US and UK elections sitting on a bedrock of future energy policies, it’s fair to assume that the group might find themselves increasingly in the spotlight as 2024 rolls on.