Poland’s paradox: blockading Ukraine trade, continuing Russia imports

On the surface, Poland's blockade of Ukrainian trucks at the border looks like defense of its farmers. But an exposé by Ukrainian journalists unmasks Poland's simultaneous embrace of now-banned imports from Russia, funneling cash to the very enemy it claims to resist.

Protests of Polish farmers against imports of Ukrainian agriculture have been ongoing for more than eleven months.

They started in April 2023, with some government restrictions on imports from Ukraine imposed in September 2023 and nearly complete border blockades renewed by farmers first in November 2023 and then in February 2024.

Currently, several dozens of Polish protesters, guarded by the police, block thousands of Ukrainian trucks at all road checkpoints between the countries, causing at least $3 billion in annual losses only in customs payments, which the Ukrainian army badly needs to purchase ammunition and equipment.

This situation is starkly at odds with Warsaw’s official stance. Poland has strongly supported Ukraine in its war against Russia, which is aided by Belarus, by providing military aid and supporting Ukrainian refugees.

As tensions around the blockade continue to rise, Poland continues to import agriculture from Russia and Belarus, a Ukrainian investigative journalist team has uncovered.

On 27 February, Ukrainska Pravda journalist Mykhailo Tkach and videographer Yaroslav Bondarenko went to Poland to film and investigate the Polish trade with Russia. They partially conducted the planned work but were detained by Polish police and interrogated about their materials, with some of the videos being deleted.

The Polish police initially denied this accusation but later backtracked, saying they were “establishing the identity” of Tkach and Bondarenko. Despite these difficulties, journalists released their material about Polish trade with Russia during the border blockade with Ukraine.

Poland’s trade with Russia and Belarus: what Tkach uncovered

During the investigation, the journalists called the Polish company Agrolok, proposing to sell rapeseed meal used to feed livestock. A journalist, who presented himself as a representative of a Belarusian company, said that the rapeseed meal was produced in Russia but will be packed in Belarus and will be Belarusian by documents. A representative of the Polish company Agrolok agreed to buy it, asking to send all the details by e-mail.

The journalists also talked to an employee of a Polish company buying Russian products, who asked to stay anonymous. He said the Poles are importing agriculture products in big bags loaded on trucks.

“Today I personally, one of thousands of managers in Poland, did the customs clearance for about a dozen vehicles [with agriculture products from Russia], you see?” the manager said.

Tkach and Bondarenko also went to the Polish-Belarusian border to see the trade volume themselves. Although only one checkpoint is opened between the countries, Koroszczyn-Kozlovichi, roughly one truck crosses the border every minute either to or from Poland, Tkach says.

“It’s 10:30 now. Behind me is a place where lorries are exiting the checkpoint. And since we’ve been here, over 100 lorries have crossed the border from Belarus to Poland. Here are no obstacles whatsoever. No protesters in sight,” Tkach said.

Poland banned importing various products from Ukraine in September 2023, which it now continues buying from Russia. For example, the amount of rapeseed meal arriving from Belarus has been increasing ever since. According to the investigation, in the three months since the ban on Ukrainian products, Poland has bought $8 million worth of rapeseed meal through Belarus.

Russian products are being transported from Russia to Belarus, where they are re-loaded. Cargo is loaded onto the Polish-registered trucks, which transport it to big Polish companies.

Journalists even identified three Polish companies among the largest Russian agricultural product buyers: Bromex, Diaspolis, and Kampol. They also filmed how these companies are receiving cargo. This information has also been confirmed using the open and closed databases Import Genius and Comtrade.

“Looking at the Polish-Belarusian border and Polish-Ukrainian border, I don’t really understand who is the aggressor country and who is fighting for freedom, a free Europe, and democracy,” Tkach said, commenting on the investigation.

“We went to the Polish-Belarusian border during the most intensive Polish blockade of checkpoints with Ukraine. Not only were agricultural products or grain blocked but occasionally also humanitarian cargo and even military equipment. On the same day, we arrived at the Polish-Belarusian border and saw hundreds of thousands of trucks coming to and fro, bringing a crazy turnover of goods, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars to Russia.”

What Poland buys from Russia and blocks from Ukraine

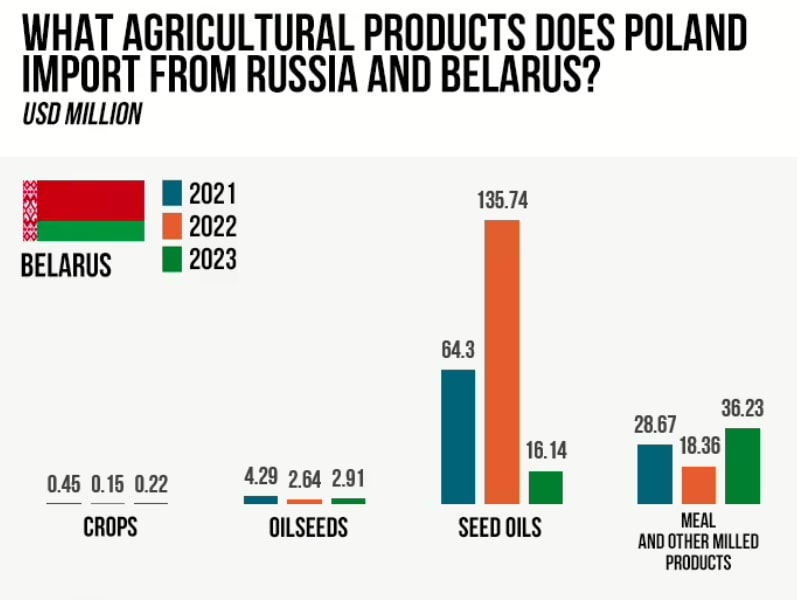

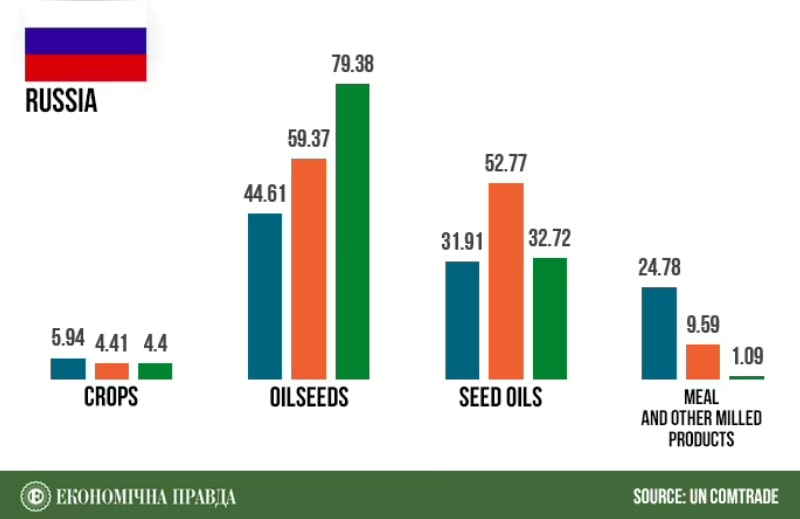

Official statistics show that in 2023, Poland continued to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to Russian and Belarusian companies for seeds, oil, and animal feed.

In some categories, it imported even more goods than before the beginning of the war against Ukraine in 2022 amid a simultaneous blockade of importing the same categories of products from Ukraine. This data was collected by Dana Hordiychuk from UN databases and presented in an article on Ukrainska Pravda.

In total, in 2023, Poland exported $6.5 billion worth of goods to Russia and Belarus. Imports from these countries stood at $3.1 billion, 50% of which were of fuel.

At the same time, Poland imported goods worth $4.8 billion from Ukraine and exported goods worth $6.6 billion to Ukraine, according to Ukrainian customs.

Data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland is even more in favor of Poland: in 2023, exports of Polish goods to Ukraine reached EUR 10 billion, while Ukrainian exports to Poland stood at EUR 4 billion. The difference is likely due to Ukraine’s partial wartime liberation of imports from Poland, as some items were imported without customs clearance or by a simplified procedure.

In any case, despite the current war, Poland’s total trade with Ukraine nearly equaled that with Russia and Belarus during 2023.

With agricultural products alone, the value of Russian and Belarusian exports to Poland reached $173 million in 2023, exceeding the pre-war 2021 figure. Notably, imports of grains and oilseeds, blocked from Ukraine since September 2023, more than doubled.

Granted, the volume of Russian and Belarusian agricultural exports to Poland was seven times smaller than those from Ukraine in 2023.

Hoever, even this scope is significant given the current total border blockade with Ukraine. Ukrainian agricultural exports to Poland have already dropped by 40% in 2023, while Russian exports have increased.

No protests or actions have been launched to prevent imports from Russia despite fears of foreign imports, unlike the campaign against Ukraine.

Economichna Pravda’s editor-in-chief Dmytro Denkov specified what exactly Russia buys from Poland and vice versa.

Poland sells primarily perfumery, household chemicals, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products to Russia. What these “pharmaceutical products” are, specifically, remains unclear.

“Early data shows that hemostatics and tactical medicine may be among pharmaceutical products,” Denkov said.

Poles also sell many machines and spare parts, other industrial products, and plastic products to Russia.

Earlier, Russia sold to Poland mainly fuel and other energy products. Currently, metals, fertilizers as well as fish, and even alcohol products comprise a significant portion of the trade.

“For example, [Russia’s] rapeseed meal exports have grown significantly after Poland banned its imports from Ukraine. […] From the point of view of common sense, [when Russian officials] threaten reducing Warsaw to ash with nuclear missiles […], it does not make much sense to strengthen your enemy by trading with him,” Denkov said.

What makes Poland’s trade with Russia and trade blockade with Ukraine possible?

In the third year of the Russian war against Ukraine, the EU is not sanctioning imports of agricultural products from Russia. This especially plays in Russia’s favor, given the availability of cheap Ukrainian products that could fully compensate for Russian imports but remain blocked on the border.

Most vehicles crossing into Poland from Belarus have Polish number plates, effectively leveraging the EU exception in its sanctions regime for haulers transporting agricultural products. Sanctions against Russian agricultural products were removed from the EU agenda under the pretext of the alleged need to save vulnerable countries from famine even though none of the EU countries, especially Poland, face the threat of famine without Russian food.

The Polish nearly-full blockade of Ukrainian road crossings at the end of 2023 didn’t lead to Ukraine’s economic peril only because by then, Ukraine’s army managed to partially unblock its Black Sea ports from Russian control.

Despite Polish farmers’ claims of an alleged “influx of cheap Ukrainian grain,” only 5% of Ukrainian agriculture was exported through Poland in 2023. After the opening of the Black Sea corridor by Ukrainian forces, 90% of Ukrainian agriculture exports go by sea, Ukraine’s Minister of Agriculture Mykola Solskyi stressed.

At the same time, the blockade affected certain industries, including the export of cables, dairy and meat products, and semi-finished products, which are exported mainly by land.

No EU sanctions against Russian food exports yet

Not a single EU country has ever considered sanctions against Russian food imports, except for Latvia, which has recently taken the first steps in this direction.

Latvia has banned the import of Russian grain at the legislative level and demanded that similar measures be taken and sanctions introduced against Russian exports to the EU at the European level since goods from Ukraine can replace all such products.

Latvian Minister of Agriculture Armands Krauze stated this on 26 February 2024 in Brussels before the EU Council of Ministers on Agriculture and Fisheries started.

“We are still asking for European sanctions to be extended to Russian grain and food products. Latvia adopted national legislation that protects us from Russian imports […] This does not affect transit to third countries, including other EU countries… Everything imported from Russia can be imported from Ukraine. And in this way, we will support Ukraine and not help Russia feed its war machine,” Krause stressed.

He noted that the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy needs to be clarified, as much has changed since its last review in 2021, and Europe now has a war on its doorstep.

Intense negotiations are also ongoing in the EU regarding the liberalized free trade with Ukraine, a decision the EU Commission made at the beginning of the Russian invasion in 2022 to support the Ukrainian economy.

Despite Ukraine’s ongoing EU integration, Polish farmers and politicians demand restricting trade with Ukraine to the pre-war level of 2021. And although the European Commission is not likely to go that far, it is likely to impose some restrictions.

Polish government softly supports farmers’ demands

The Polish government so far hasn’t condemned the actions of Polish farmers, giving tacit agreement to the economic blockade of Ukraine.

At the same time, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk suggested the possibility that Poland may impose a ban on imports of agricultural products from Russia, following the example of Latvia.

“Latvia decided to implement an embargo on the import of (agricultural) products from Russia,” Donald Tusk said. “We will analyze the case of Latvia, and I do not rule out that Poland will take an appropriate initiative.“

On 22 February, Tusk also suggested that border crossings with Ukraine and sections of roads and railways will be included in the list of Polish critical infrastructure. This should provide “a 100% guarantee that military and humanitarian aid will reach the Ukrainian side without delay,” he said.

Earlier, regarding the farmers’ demands, the Prime Minister noted that the government will convince “both Kyiv and Brussels so that they begin to understand and accept the Polish point of view on this issue.”

Polish journalist Piotr Andrusieczko commented on Tusk’s decision to include rails and roads into critical infrastructure as a “strange situation:”

“To be honest, in Poland, it is difficult even to smoke on the platform near railways because the police will immediately appear and fine you. Here, it turns out that it is possible that someone can come in, do something with the cars, spill 160 tons of the grain… Tusk said that they will register this as critical infrastructure. But it was clear that this infrastructure was critical from the very beginning. It should have been protected more. This is the question that many people in Poland actually ask.”

Other Polish experts admit that Polish farmers face problems, caused in part by cheaper Ukrainian products and in part by strict EU regulations, including the EU’s “Green Deal,” which increases their production costs. The form of the protest is, however, unacceptable, says Dariusz Szymczycha, First Vice-President of the Polish-Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce:

“The problems they face are real, but blocking the border is unacceptable.”

Ukrainian transport companies also don’t need to meet EU requirements for drivers’ wages or working hours – this is another chief reason for the Polish haulers’ protests:

How to unblock the Ukrainian-Polish border crossing for good

Blockade’s only achievement will be increasing inflation in EU, Ukraine says

Mykola Solskyi, Ukraine’s Minister of Agriculture, stressed that, on the one hand, global grain prices are very low for the second year in a row and will continue to fall. This applies to any Ukrainian, Polish, or other farmer. This gives rise to many ” unnecessary emotions, but to eliminate them, you have to work with them.”

First of all, exports from Russia and Belarus to the EU should be banned, he said:

“[Agriculture] exports from Russia and Belarus to EU countries, including Poland, are increasing; this is completely off the mark.”

Moreover, current debates in the EU propose increasing restrictions on imports from Ukraine to include its cheaper sugar and some other products, Solskyi said.

He points out that this policy is sure to hit consumers. Sugar prices in the EU have jumped twice since the start of Russia’s war, but if imports are restricted even further, it is likely to stimulate prices to rise even more, benefitting large sugar producers.

“And do we also restrict sugar imports, for example, from Brazil, or are we only speaking about Ukrainian sugar?” Solskyi asked rhetorically, pointing out the anti-Ukrainian nature of these discussions.

Denys Marchuk, Deputy Head of the Ukrainian Agriculture Council, believes that the idea that Ukrainian imports into the EU led to the collapse of prices and that Ukrainians are overwhelming the EU market is misguided

Although competition in some sectors, in particular truck logistics in Poland, did increase, it is far from systemic. The total turnover of goods between Ukraine and the EU is even smaller than between the EU and Russia. Ukraine’s agricultural exports to the EU do not hinder European producers.

For example, the EU consumes about 12 million tons of poultry annually. Ukraine’s exports to the EU stand at 200,000 tons — no more than 2-3%. Such volumes cannot kill the producer in France or Poland.

Similar statistics apply to sugar. Ukrainian sugar exports to the EU are also within 2% of the consumption. Eggs do not even reach 1%, Marchuk stresses.

“4.5 million Ukrainians left Ukraine [after the outbreak of war] and live in the EU, including in Poland; these people consume products. Ukrainian exports to the EU in most categories barely covers the sole needs of Ukrainians in the EU,” Marchuk said. “Unfortunately, we really see this issue becoming politicized.”

Yaroslav Zhelezniak, a Ukrainian MP from the Holos Party, highlights tremendous losses to the Ukrainian budget due to the border blockade, which also hinders Ukraine’s capabilities to continue defending itself against Russian aggression.

Due to the blockade, Ukraine’s budget loses UAH 8 billion ($240 million) monthly in customs payments alone.

This makes for almost $3 billion of annual losses in customs payments, apart from other taxes and losses of entrepreneurs.

“I want to stress that we currently fund the entire army through taxes and customs payments, which we can use for military needs. These are funds that were taken directly from the army budget, and unfortunately, we will have to find a way to balance the system somehow,” Zhelezniak said.

Ukrainian journalists detained, “humiliated” by Polish police

Ukrainian journalist Mykhailo Tkach, who was detained by Polish police, said he experienced humiliating treatment on top of being prevented from doing his job as a journalist. Tkach expressed outrage that the situation was only resolved after it became public knowledge and the Ukrainian Embassy in Poland intervened.

“About ten people began to search our car, us, threw our things on the hood, retrieved all the memory cards from the cameras, took all the phones, documents,” Tkach said. “During the interrogation at the commandant’s office, I said that we were filming how Poland trades with Russia through Belarus. It was clear that the representatives of the Polish police were frightened. They started asking me who else knew about it, whether the Ukrainian authorities or the Ukrainian government knew about it. They asked who our sources are.“

The journalists were not allowed to phone a lawyer, and no interpreter from the Polish language was provided. Polish servicemen allowed themselves to speak numerous humiliating phrases because Tkach was a Ukrainian journalist, such as “Go back to your Ukraine.”

Tkach expresses frustration that Polish police are eager to detain Ukrainian journalists, yet fail to protect 160 tons of Ukrainian grain destroyed on the railway.

As Tkach states:

“It’s a spectacle that no one detains the people who spilled the grain, but the journalist who filmed from the roadside is considered a strategic threat. The journalist was standing in a parking lot near the road, and ten police officers worked against him, plus the special service.“

The Polish police briefly responded to the incident, saying they were only confirming the identities of the journalists:

“Police officers from the Lublin garrison took action to confirm the identities of people whose presence in the border area caused concern for residents. After verifying their identities, the people left the police station.“

Tensions are running extremely high on the Polish-Ukrainian border, with Polish and Ukrainian government officials expected to meet on 28 March in an attempt to find a solution.

Notably, Ukraine has indicated that the blockade could become a story that goes both ways. Polish exports to Ukraine are at least 1.5 higher than Ukrainian exports to Poland, with processed food the main category, meaning that Poland benefits more from its trade with Ukraine.

Ukrainian officials, including President Zelenskyy, have dropped hints that they are ready to “protect Ukrainian businesses,” in particular by closing the border. However, such measures have not yet been applied in the hope of meaningful negotiations with Polish government.

Read more:

- Polish protesters block all six checkpoints with Ukraine

- How to unblock the Ukrainian-Polish border crossing for good

- Grain dispute: how Poland and Ukraine can reach a solution

- Ukrainians deported from Poland in 1944 recall mass killings, explain paths to historical reconciliation

You could close this page. Or you could join our community and help us produce more materials like this.

We keep our reporting open and accessible to everyone because we believe in the power of free information. This is why our small, cost-effective team depends on the support of readers like you to bring deliver timely news, quality analysis, and on-the-ground reports about Russia's war against Ukraine and Ukraine's struggle to build a democratic society.

A little bit goes a long way: for as little as the cost of one cup of coffee a month, you can help build bridges between Ukraine and the rest of the world, plus become a co-creator and vote for topics we should cover next. Become a patron or see other ways to support.