Politicize Hurricane Milton, Please

Hurricane Milton is hurtling toward Florida. Some 5.5 million people there—roughly the population of Norway—have been ordered to evacuate. In just 12 hours Milton transformed from a Category 1 storm into a Category 5 storm, over unusually hot waters in the Gulf of Mexico. If you visit the Climate Central website to try to look at precisely how hot those waters are, you could be greeted with a notification that the numbers may be out of date. That’s because a key federal institution responsible for gathering that data—the National Centers for Environmental Information, run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA—is still experiencing outages after its Asheville, North Carolina, headquarters was knocked offline last week by Hurricane Helene; as of Monday, NOAA wasn’t sure when it’d be fully operational. Many of the Florida communities likely to be hardest hit by Milton are similarly still trying to clean up the wreckage of that storm.There’s much, much more of this to come. News of Milton’s newfound strength broke as some of the world’s leading climate scientists released a sobering new report. “We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster,” they write, going on to provide a list of disasters over the last year all at least partly attributable to climate change. “We are currently going in the wrong direction, and our increasing fossil fuel consumption and rising greenhouse gas emissions are driving us toward a climate catastrophe.” Yet this catastrophe hasn’t been a major focus of the 2024 presidential campaigns. The choice between Republicans and Democrats in November on climate is a clear one: Trump and his allies have spread dangerous lies about federal relief efforts that could keep survivors from seeking much-needed help, continually denied the reality of climate change, and vowed to supercharge fossil fuel production while “breaking up and downsizing” NOAA, along with every other facet of what Project 2025 dubs the “climate change alarm industry.” Harris would not do those things. But she also hasn’t talked all that much about what she would do to deal with the climate crisis—even as climate-fueled storms ravage the country. Since Hurricane Helene hit, she’s condemned Republican misinformation about hurricane relief and visited survivors, helping to distribute food deliveries. Biden linked “storms getting stronger” to the climate crisis when visiting North Carolina in recent weeks; onstage at the vice presidential debate, Walz similarly noted that Helene “roared onto the scene faster and stronger than anything we’ve seen.” That’s not the same as outlining a plan to limit the damage from these storms in the future. Harris has largely dodged the topic of climate change for months. She may be worried about being associated with the “far-left Green New Deal,” which Republican-aligned PACS have run attack ads about in Pennsylvania and Michigan. In the case of the storms, Harris may also be eager to avoid accusations—like those now coming from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis—of “politicizing” them.The ways that societies deal with storms like Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton are inherently political, though—in ways that Harris should talk openly about. Republicans, after all, are the party of putting people in harm’s way. Trump has invited the oil and gas companies helping to supercharge storms to write his policies. In recent weeks, Republican members of Congress voted against critical disaster relief funds. In Florida, DeSantis has showered his donors in the insurance industry—now charging five times the national average for home insurance there—with lavish giveaways, never mind the fact that people whose homes have been washed away might not be able to afford to rebuild them.Like Biden, Harris and her advisers talk about climate change mainly insofar as it’s a reason to spur investments in electric vehicles, solar panels, and other low-carbon technologies. Obama and Biden White House alum Brian Deese—a driving force behind the Inflation Reduction Act, who’s been advising Harris—recently described climate policy principally as a way to unlock “billions of dollars of market opportunities” for U.S. companies abroad while ending China’s dominance in strategic twenty-first-century growth industries. Harris, similarly, pledged at a campaign event pitching her economic vision in Pittsburgh last month to “recommit the nation to global leadership in the sectors that will define the next century.” A core pillar of her campaign’s pitch for an “opportunity economy” is “leading the world in the industries of the future and making sure America, not China, wins the competition for the twenty-first century.” On stage at last week’s vice presidential debate, JD Vance and Tim Walz found common ground in wanting to “reshore as much American manufacturing as possible” and “produce as much energy as possible in the United States of America,” as Vance put it. Walz went on to boast about the

Hurricane Milton is hurtling toward Florida. Some 5.5 million people there—roughly the population of Norway—have been ordered to evacuate. In just 12 hours Milton transformed from a Category 1 storm into a Category 5 storm, over unusually hot waters in the Gulf of Mexico. If you visit the Climate Central website to try to look at precisely how hot those waters are, you could be greeted with a notification that the numbers may be out of date. That’s because a key federal institution responsible for gathering that data—the National Centers for Environmental Information, run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA—is still experiencing outages after its Asheville, North Carolina, headquarters was knocked offline last week by Hurricane Helene; as of Monday, NOAA wasn’t sure when it’d be fully operational. Many of the Florida communities likely to be hardest hit by Milton are similarly still trying to clean up the wreckage of that storm.

There’s much, much more of this to come. News of Milton’s newfound strength broke as some of the world’s leading climate scientists released a sobering new report. “We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster,” they write, going on to provide a list of disasters over the last year all at least partly attributable to climate change. “We are currently going in the wrong direction, and our increasing fossil fuel consumption and rising greenhouse gas emissions are driving us toward a climate catastrophe.”

Yet this catastrophe hasn’t been a major focus of the 2024 presidential campaigns. The choice between Republicans and Democrats in November on climate is a clear one: Trump and his allies have spread dangerous lies about federal relief efforts that could keep survivors from seeking much-needed help, continually denied the reality of climate change, and vowed to supercharge fossil fuel production while “breaking up and downsizing” NOAA, along with every other facet of what Project 2025 dubs the “climate change alarm industry.”

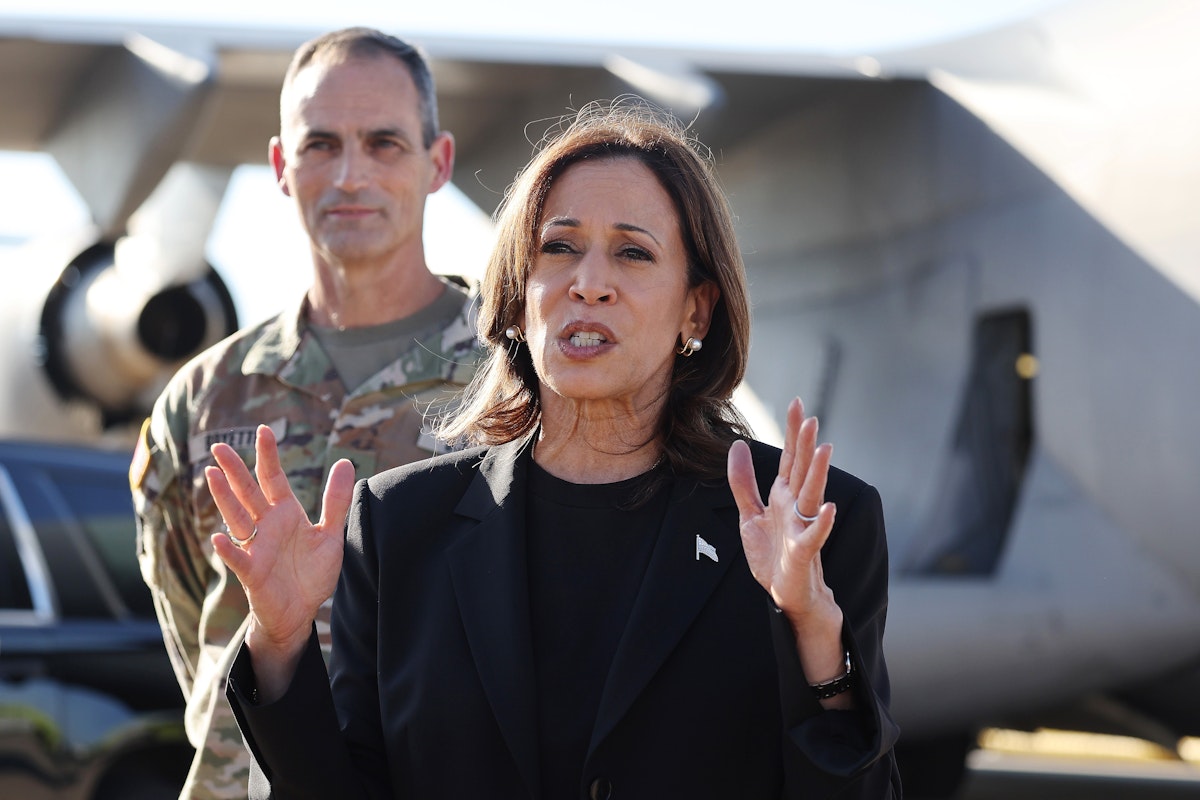

Harris would not do those things. But she also hasn’t talked all that much about what she would do to deal with the climate crisis—even as climate-fueled storms ravage the country. Since Hurricane Helene hit, she’s condemned Republican misinformation about hurricane relief and visited survivors, helping to distribute food deliveries. Biden linked “storms getting stronger” to the climate crisis when visiting North Carolina in recent weeks; onstage at the vice presidential debate, Walz similarly noted that Helene “roared onto the scene faster and stronger than anything we’ve seen.” That’s not the same as outlining a plan to limit the damage from these storms in the future.

Harris has largely dodged the topic of climate change for months. She may be worried about being associated with the “far-left Green New Deal,” which Republican-aligned PACS have run attack ads about in Pennsylvania and Michigan. In the case of the storms, Harris may also be eager to avoid accusations—like those now coming from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis—of “politicizing” them.

The ways that societies deal with storms like Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton are inherently political, though—in ways that Harris should talk openly about. Republicans, after all, are the party of putting people in harm’s way. Trump has invited the oil and gas companies helping to supercharge storms to write his policies. In recent weeks, Republican members of Congress voted against critical disaster relief funds. In Florida, DeSantis has showered his donors in the insurance industry—now charging five times the national average for home insurance there—with lavish giveaways, never mind the fact that people whose homes have been washed away might not be able to afford to rebuild them.

Like Biden, Harris and her advisers talk about climate change mainly insofar as it’s a reason to spur investments in electric vehicles, solar panels, and other low-carbon technologies. Obama and Biden White House alum Brian Deese—a driving force behind the Inflation Reduction Act, who’s been advising Harris—recently described climate policy principally as a way to unlock “billions of dollars of market opportunities” for U.S. companies abroad while ending China’s dominance in strategic twenty-first-century growth industries. Harris, similarly, pledged at a campaign event pitching her economic vision in Pittsburgh last month to “recommit the nation to global leadership in the sectors that will define the next century.” A core pillar of her campaign’s pitch for an “opportunity economy” is “leading the world in the industries of the future and making sure America, not China, wins the competition for the twenty-first century.” On stage at last week’s vice presidential debate, JD Vance and Tim Walz found common ground in wanting to “reshore as much American manufacturing as possible” and “produce as much energy as possible in the United States of America,” as Vance put it. Walz went on to boast about the U.S. producing more oil and gas “than we ever have,” a stance reiterated in the single paragraph on climate and energy on the campaign’s website.

Pouring hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of tax incentives into green energy is certainly helpful to the cause of reducing emissions. Yet there’s a strange disconnect between Democrats describing climate change primarily as an economic opportunity and the tens of billions of dollars’ worth of damages that it’s doling out. Reducing emissions is a relatively minor part of the pitch for green industrial policies like the Inflation Reduction Act, the core focus of which is to make green technologies more attractive to investors.

The sorts of expanded state capacities needed to protect against climate disasters like Hurricane Milton—things like storm-resilient infrastructure, more robust disaster response, and managed retreat—don’t promise steady returns to Wall Street. People whose homes have been destroyed in North Carolina also probably don’t care all that much about all the jobs being created by a new solar manufacturing plant in Minnesota.

It’s possible to talk about the very real benefits of investing in things that will mitigate climate change without ignoring all the havoc it’s creating. Trump and the GOP are especially vulnerable on the latter point; Republican politicians continue to make life for their constituents more dangerous and expensive. Democrats should face those failures and the destructive reality of the climate crisis head-on, and make it clear that they’re prepared to navigate a warming world more adeptly and humanely. If they don’t, Republicans will keep capitalizing on disaster victims’ pain and fear to win votes and raise temperatures.