Remembering Vint Lawrence

The most gifted illustrator in The New Republic’s 110-year history was a former Central Intelligence Agency counterinsurgent named Vint Lawrence. In 1960, James Vinton Lawrence, then a graduating art history major at Princeton, was recruited by the Company to train Hmong tribesmen in the Laotian mountains to fight the Communist Pathet Lao. Eventually, Vint grew disillusioned with the long twilight struggle and became an artist instead. He landed in the late 1970s at The New Republic, where over 30-odd years he accumulated a ravishing portfolio. We thought that an anniversary issue was the perfect occasion to remind old TNR readers, and tell new ones, of Vint’s deft and graceful touch.The preeminent highbrow caricaturist at that time was David Levine of The New York Review of Books. Levine had a dark and often angry style; he once drew Henry Kissinger literally fucking the world. By contrast, Vint—perhaps because he’d had his fill of darkness in Southeast Asia—drew in a sunnier and more playful vein, especially when sketching the liberal pantheon. That’s Lyndon Johnson in Franklin Roosevelt’s side-view mirror; John F. Kennedy is FDR’s steering-wheel ornament. Mario Cuomo, famously a devotee of the cosmic theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, is a head floating above mere wisps of a corporeal frame. Where Vint’s drawings possess darkness, it’s usually to contrast with light; note the pitch black behind the lively waves and crevices of Ted Kennedy’s face and the quieter elegance of Eleanor Roosevelt. (These depictions of Mr. and Mrs. Roosevelt, incidentally, did not appear in TNR’s pages; they were perhaps created for The Washington Post or Washington Monthly, two other outlets where Vint contributed occasionally.)Vint’s personal kindness and intelligence were reflected in the gentle wit of his caricatures. These were sometimes more prescient than the articles they illustrated. In the 1980s, TNR opposed Jesse Jackson’s efforts to tug centrist Democrats leftward in two presidential runs. Four decades later, much of Jackson’s program lies well within the Democratic mainstream, rendering the affection evident in Vint’s Jackson portrait more durable than whatever grumpy TNR article it likely accompanied.“Vint uses his talent for intricacy more often for aesthetic than didactic purposes,” former TNR editor Michael Kinsley observed in 1988. It’s no surprise to learn that, after Vint left The New Republic, he turned to painting, which he pursued until his death in 2016. His was a buoyant spirit that inspired all who knew him and endures in these drawings.

The most gifted illustrator in The New Republic’s 110-year history was a former Central Intelligence Agency counterinsurgent named Vint Lawrence. In 1960, James Vinton Lawrence, then a graduating art history major at Princeton, was recruited by the Company to train Hmong tribesmen in the Laotian mountains to fight the Communist Pathet Lao. Eventually, Vint grew disillusioned with the long twilight struggle and became an artist instead. He landed in the late 1970s at The New Republic, where over 30-odd years he accumulated a ravishing portfolio. We thought that an anniversary issue was the perfect occasion to remind old TNR readers, and tell new ones, of Vint’s deft and graceful touch.

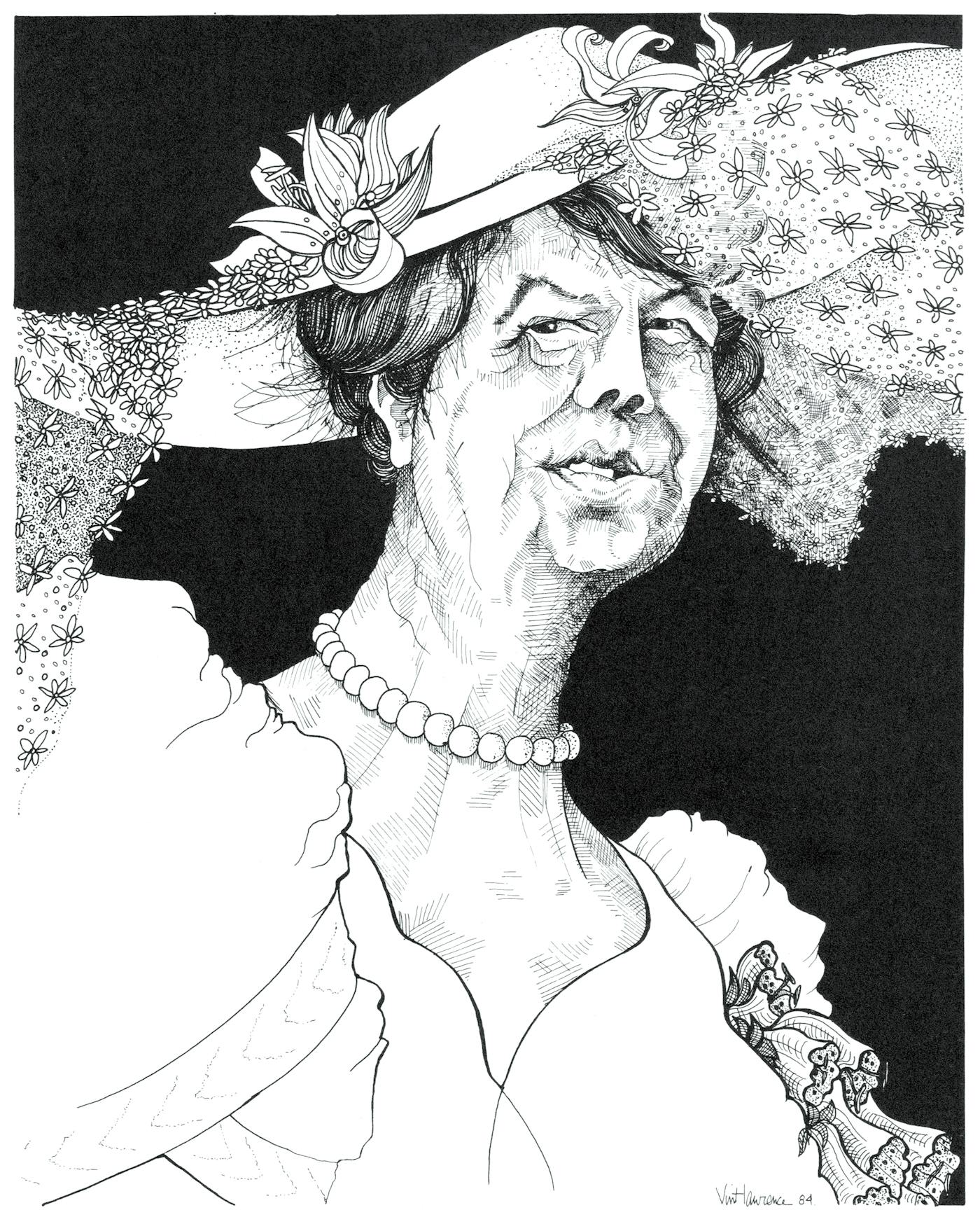

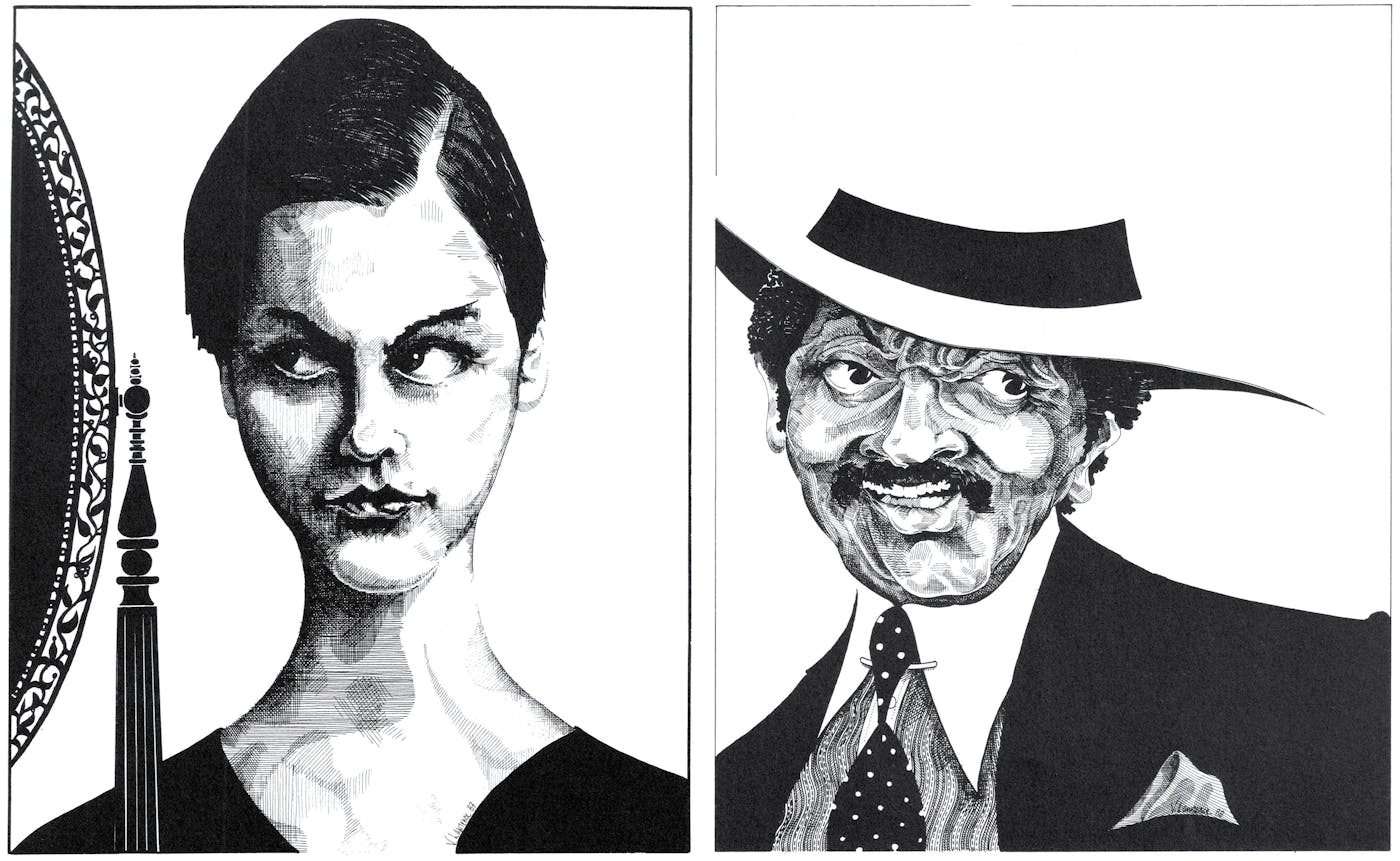

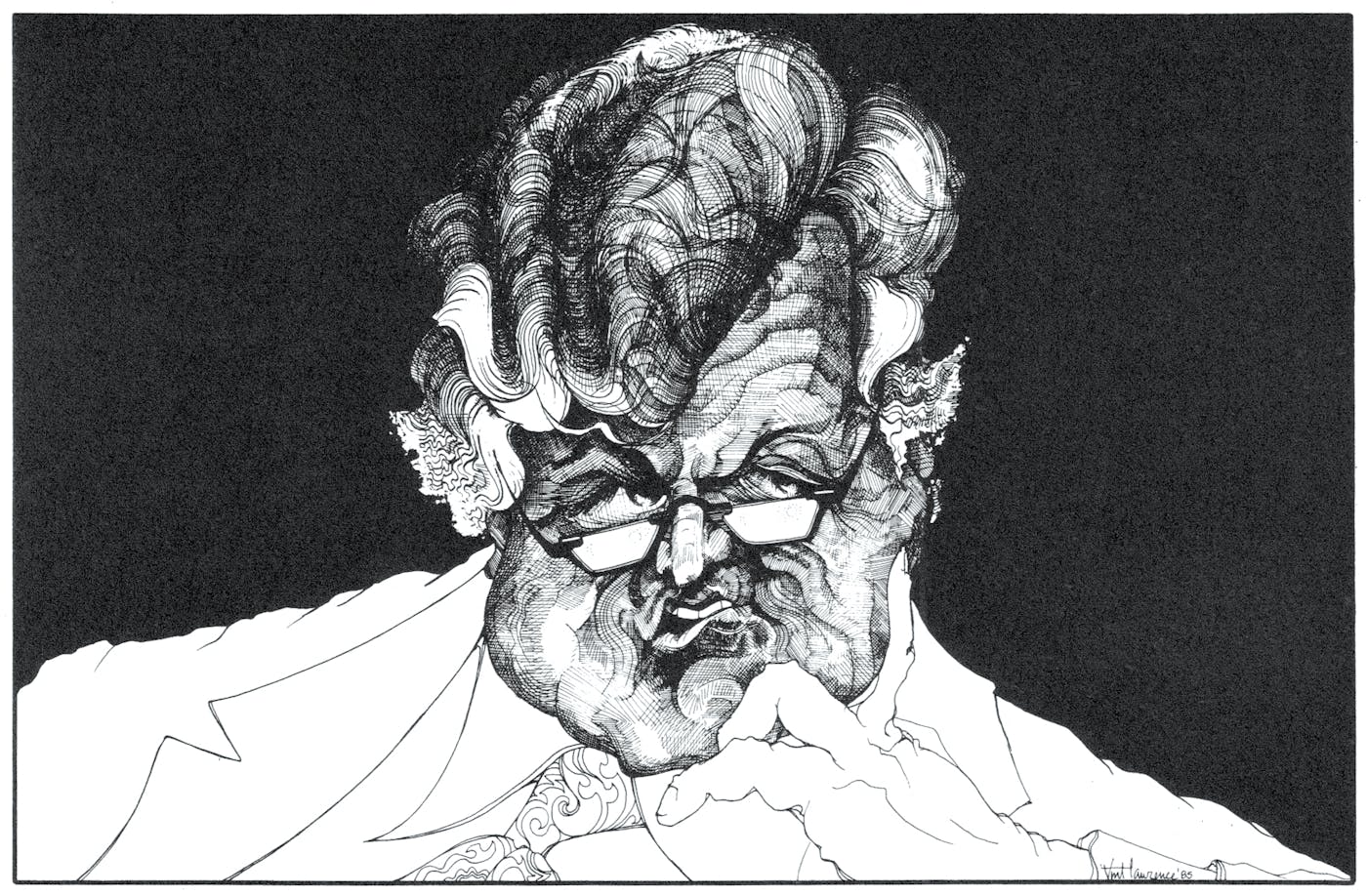

The preeminent highbrow caricaturist at that time was David Levine of The New York Review of Books. Levine had a dark and often angry style; he once drew Henry Kissinger literally fucking the world. By contrast, Vint—perhaps because he’d had his fill of darkness in Southeast Asia—drew in a sunnier and more playful vein, especially when sketching the liberal pantheon. That’s Lyndon Johnson in Franklin Roosevelt’s side-view mirror; John F. Kennedy is FDR’s steering-wheel ornament. Mario Cuomo, famously a devotee of the cosmic theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, is a head floating above mere wisps of a corporeal frame. Where Vint’s drawings possess darkness, it’s usually to contrast with light; note the pitch black behind the lively waves and crevices of Ted Kennedy’s face and the quieter elegance of Eleanor Roosevelt. (These depictions of Mr. and Mrs. Roosevelt, incidentally, did not appear in TNR’s pages; they were perhaps created for The Washington Post or Washington Monthly, two other outlets where Vint contributed occasionally.)

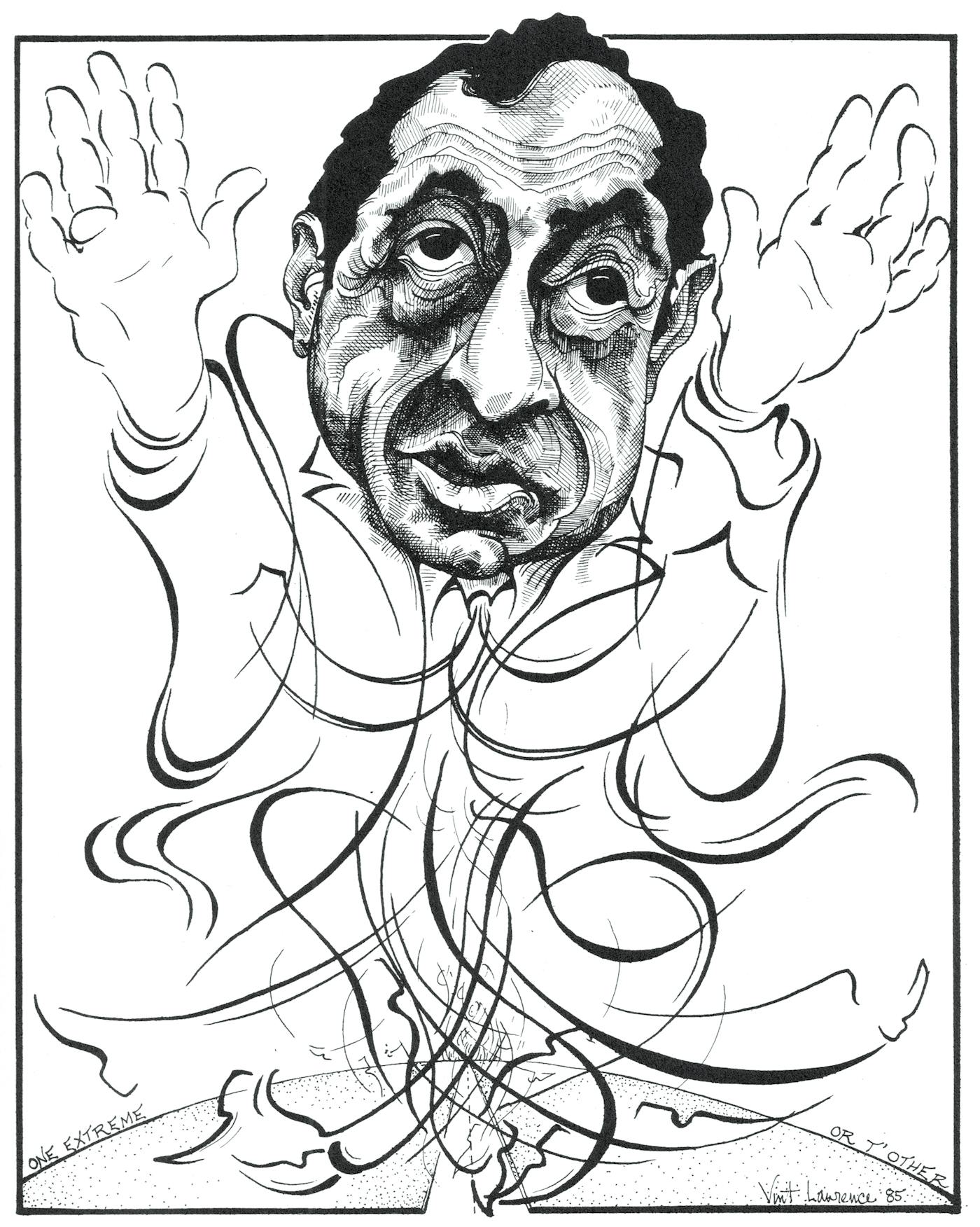

Vint’s personal kindness and intelligence were reflected in the gentle wit of his caricatures. These were sometimes more prescient than the articles they illustrated. In the 1980s, TNR opposed Jesse Jackson’s efforts to tug centrist Democrats leftward in two presidential runs. Four decades later, much of Jackson’s program lies well within the Democratic mainstream, rendering the affection evident in Vint’s Jackson portrait more durable than whatever grumpy TNR article it likely accompanied.

“Vint uses his talent for intricacy more often for aesthetic than didactic purposes,” former TNR editor Michael Kinsley observed in 1988. It’s no surprise to learn that, after Vint left The New Republic, he turned to painting, which he pursued until his death in 2016. His was a buoyant spirit that inspired all who knew him and endures in these drawings.