Russia weaponizes history to erase Crimean Tatar identity

As an exiled Crimean Tatar journalist, I've witnessed my people's desperate struggle to preserve our language, traditions, and very existence in the face of renewed Russian oppression.

Ask anyone in the West about the Crimean peninsula, and the answer is predictable: “It’s a complicated story.” What follows illustrates that they know Crimea through Russian narratives.

This is no surprise. For many years, Western audiences knew Ukraine as simply part of Russia, and thus, the nature of the Russo-Ukrainian War was difficult to grasp. On the third year of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Western audiences are just beginning to understand that Ukrainians and Russians are different people.

However, the history of Crimea and its people still remains invisible. If you speak to Westerners about Crimea’s indigenous Muslim people, the Crimean Tatars, you are often met by surprise, followed by a pause and only then questions.

As a Crimean Tatar whose only homeland is Crimea, I often encounter this unfamiliarity with my homeland. Unfortunately, longstanding propaganda and myths rooted in the teaching of Russian literature, religious traditions, and history have demonized the Crimean Tatar people.

Before the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea, I worked as a journalist for the Crimean Tatar channel ATR, hosting programs in our native language. Life was fulfilling; I was living in my native homeland and was dedicated to reviving the Crimean Tatar language and culture through my journalism and television reporting.

However, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 changed everything. The occupation authorities shut down the Crimean Tatar ATR TV channel, accusing it of extremism. My colleagues and I were forced to leave our homeland and relocate to Kyiv, as there no longer was a need for honest, objective journalism in occupied Crimea. Currently, I am a visiting scholar at the University of Cambridge, where I am engaged in studying the history of Crimea.

Russia’s destruction of Crimean Tatar heritage started with first annexation of Crimea in 1783

The annexation of Crimea in 2014, which was marked by unlawful arrests, searches, and the forcible expulsion of Crimean Tatars from their ancestral land, has a disturbing precedent—the first Russian annexation of Crimea in 1783.

Today, the authorities in occupied Crimea illegally accuse the Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians of extremism. This also has a historical precedent. After the first invasion in 1783, the Russian Empress Catherine I and the Russian tsars who followed her regarded the Crimean Tatars as a dangerous Turkic and Muslim population that should be exterminated.

The colonial policy systematically discriminated against the Crimean Tatars, who, in the 18th and 19th centuries, made up the majority of the peninsula’s population and took pride in their rich cultural inheritance and superior education system.

The intolerance toward the Crimean Tatars included the desecration of Islamic religious sites and the leveling of 1,500-1,700 mosques. The palaces of the Crimean khans were replaced by Russian aristocratic estates and Russian Orthodox churches in an attempt to eradicate the heritage and memory of the Tatars in Crimea.

Russian historiography perpetuated this disparaging narrative of a vandalous Crimean Tatar nation and obfuscated the centuries-old history of the Crimean Khanate to justify the oppressive measures imposed to achieve Russian hegemony.

In reality, the Crimean Khanate (1441-1783) was a flourishing state, as highlighted by numerous prominent scholars who have studied the Crimean peninsula, such as professors Alan Fisher, Rory Finnin, Brian G. Williams, and Donald Rayfield. Ukrainian orientalist Mykhailo Yakubovych dedicated an entire book to the philosophical thought of the Crimean Khanate period, establishing that Crimean Tatar philosophy rivaled Christian and European philosophical traditions.

It is noteworthy that the very name “Crimea” is of Crimean Tatar/Turkic origin and translates as “defensive ditch” or “fortress.” In addition, before the Russification of Crimea, the toponyms of the peninsula, the names of cities, villages, lakes, rivers, and mountains bore Crimean Tatar names.

Kyivan Rus baptism myth as a driver of Russification of Crimea

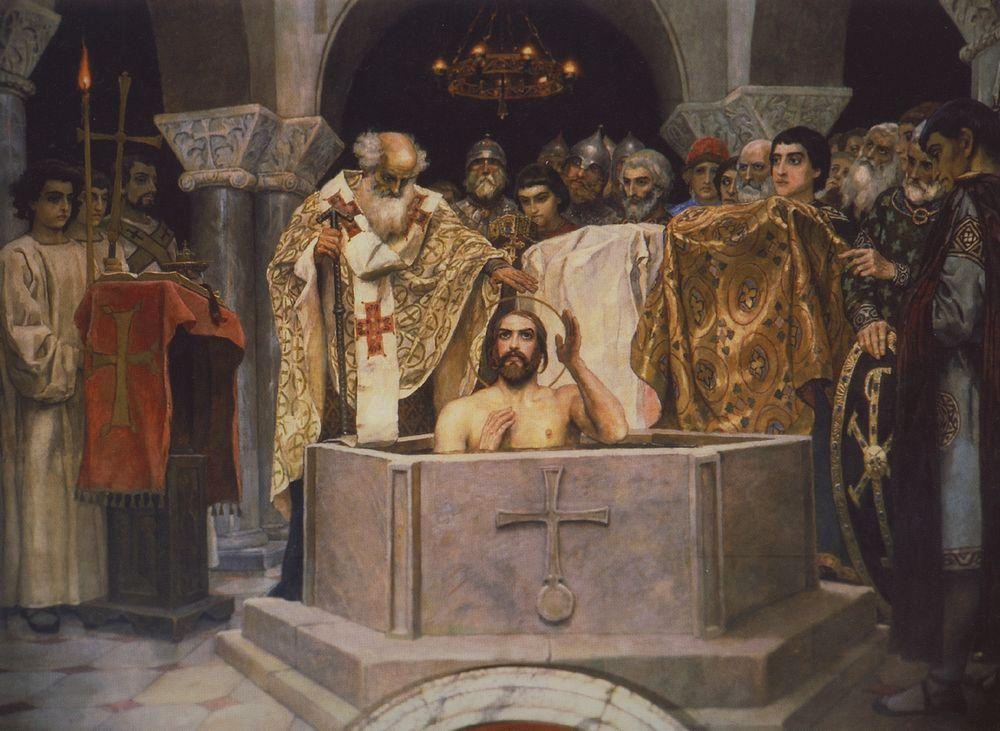

The Russian imperial and Soviet governments used various methods to assert Russian hegemony on the Crimean peninsula, including the Christianization of Crimea’s past. Russian historians promoted a myth linking the 988 baptism of Kyivan Rus’ Grand Prince Volodymyr I with Crimea. They used this myth to present the peninsula as a “primordially Russian land.” Yet, in 988, there were no people called “Russians” and no such state as “Russia.”

The baptism of Grand Prince Volodymyr took place in the medieval period referred to in scholarship as “Kyivan Rus.” Volodymyr was the grand prince of Kyiv, and Moscow did not exist.

In Anglophone publications, however, the term Rus is often confused with Russia, and the transliteration of personal and place names is done from Russian rather than from the various languages of countries that claim the Rus’ inheritance. Such actions extend imperialist practices to the contemporary understanding not just of Crimea but of the broader lands of Eastern Europe.

The propagandistic use of the narrative associated with the baptism of Grand Prince Volodymyr has served as a starting point in the Russification and Christianisation of the Crimean peninsula.

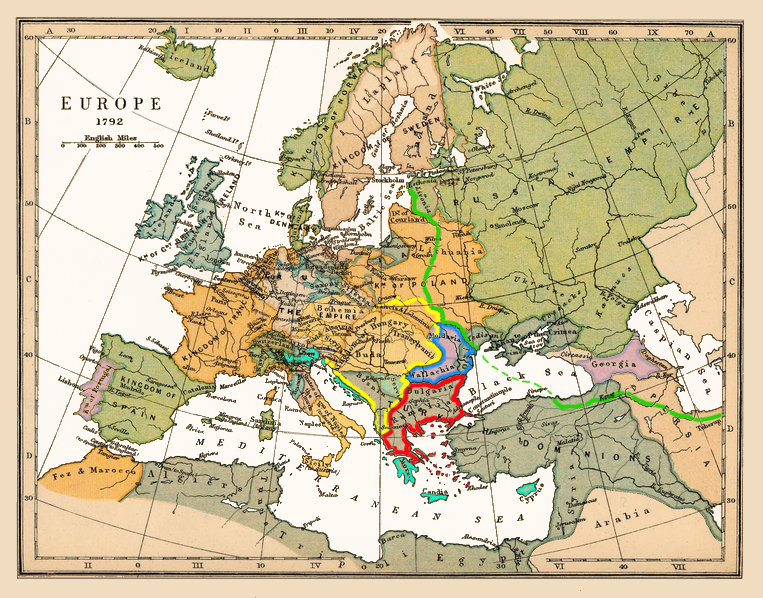

Russian imperial “Greek project” as driver of Crimean Tatar suppression

Another tool of propaganda employed by Catherine the Great was the so-called “Greek Project,” a late 18th-century strategy to cement Russia’s presence in the peninsula. This strategy, central to the myth of a historically Russian Crimea, involved building Greek Orthodox monasteries and churches, establishing Russian settlements and military bases, and suppressing Crimean Tatar resistance.

In 1778, Catherine deported the Greek Christian population from Crimea, claiming that she was doing so to protect them from the Crimean Tatar Muslims. However, religious tolerance and multi-ethnic interactions marked the historical landscape of the Crimean Khanate. The peninsula even hosted three Orthodox theological schools.

Notably, the predominant language in Crimea was Crimean Tatar, which was spoken by the entire population, including the Greek community. This linguistic preponderance of the Crimean Tatar language could have been a significant obstacle to the Russification of the peninsula. Because of the falsification of the historical past by Russian imperial and Soviet policies, as well as the physical genocide of the Crimean Tatar people, the ethnic composition of the peninsula changed. As a result, the truth about Crimea remains little known.

The suppression of the material and intellectual legacy of the Crimean Tatars culminated in the 1944 deportation carried out by Soviet authorities. Hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported to Central Asia and Siberia, where many died of starvation, disease, and harsh conditions. 46% of the Crimean Tatar population was lost in this act of genocide.

Due to Russia’s exterminatory policy, Crimean Tatars have gone from being a majority to a minority population on the peninsula. My parents and I belong to a generation born and raised in places of exile. For almost 50 years, the Crimean Tatars continued their fight to return to their historic homeland. They mounted hunger strikes and, as political dissidents, were sentenced to long prison terms in Russia’s penal colonies. The Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea en masse after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea again and mounted another wave of suppressive measures on the indigenous Crimean Tatar and pro-Ukrainian populations in Crimea. They revived the myth of “Russian Crimea.”

Monuments to Catherine II began to appear on the peninsula, and the cult of her regime, which was established in 1783 and aimed to exterminate Crimean Tatars, has grown stronger.

For the past ten years, Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians have been under constant psychological pressure and threat of physical violence. The ongoing persecution and deliberate expulsion of the Crimean Tatars from their native land could lead to the complete extermination of the indigenous people of the Crimean Peninsula. Only through the restoration of international law and democratic values can the policy of genocide be prevented in the peninsula.

Editor’s note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press’ editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

Related:

- Ten things about the Crimean Tatar deportation you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

- Crimea was always a multicultural hodgepodge

- Poland recognizes Russian deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944 as genocide

- Why this Crimean Tatar Muslim woman gives the Russian occupation authorities a headache

- The myth of “historically Russian Crimea”: colonialism, deconstructed