Russia’s “Azerbaijani gas” ploy threatens to unravel EU sanctions on Moscow

Energy expert Mykhailo Gonchar exposes Russia's audacious plan to rebrand its gas as "Azerbaijani" for transit through Ukraine, revealing how Kyiv faces mounting pressure from Moscow's European proxies to accept a deal that could shatter Western sanctions.

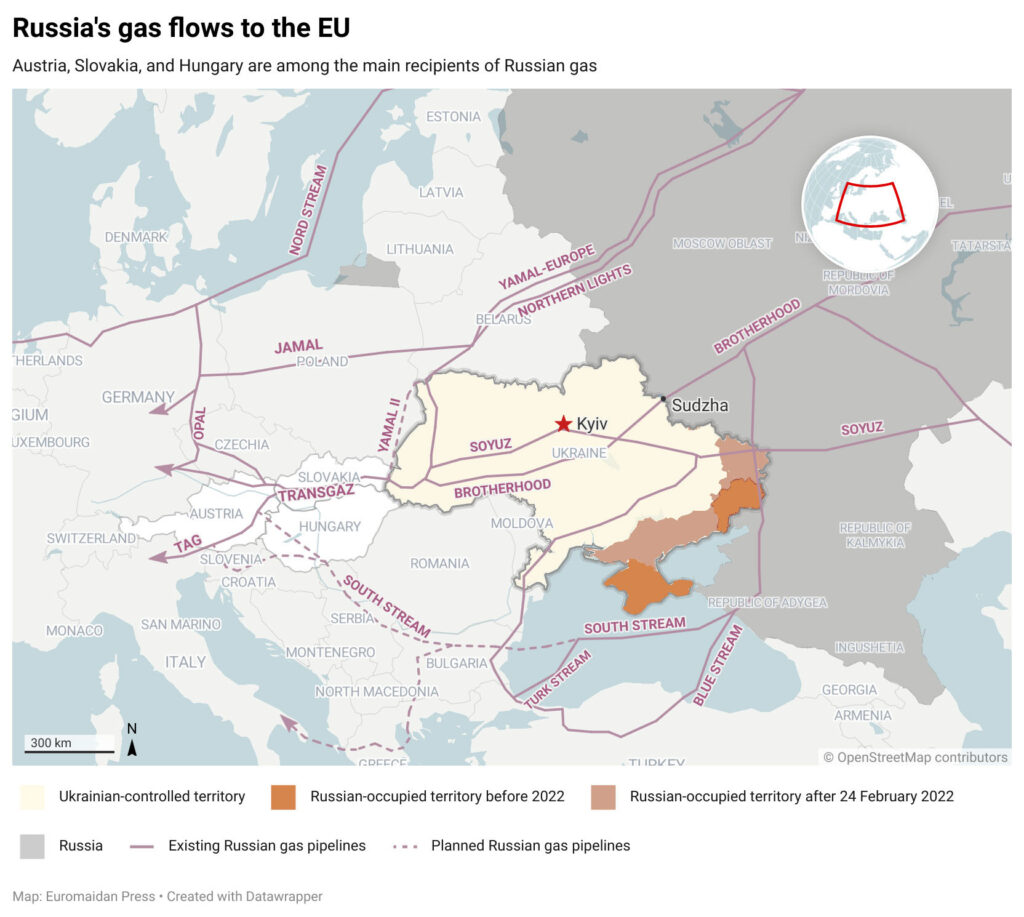

As the contract between Ukraine’s Naftogaz and Russia’s Gazprom nears its end in just over two months, Kyiv has declared it won’t be renewed. This decision could halt the flow of Russian gas to Europe through this pipeline, impacting an annual volume of about 14 billion cubic meters – a $5 billion yearly revenue for Russia and $800 million for Ukraine.

Last week, European Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson stated that Brussels isn’t concerned, emphasizing that the EU can manage without Russian gas. She warned that any continued imports by member states would be “a dangerous political choice” rather than a necessity.

Despite this stance, Hungary, Austria, and Slovakia remain reluctant to forgo Russian gas. Slovakia’s pro-Russian Prime Minister Robert Fico is particularly vocal, advocating for a scheme to replace Russian gas with Azerbaijani supplies.

However, Ukrainian energy expert Mykhailo Gonchar warns that this seemingly simple solution masks a complex Russian strategy. He argues the proposed Azerbaijani gas scheme is flawed because:

- There’s no direct pipeline route from Azerbaijan to Ukraine bypassing Russia.

- Azerbaijan lacks sufficient gas production capacity to fill Ukraine’s pipeline needs.

Gonchar suggests Russia could easily use Azerbaijani gas as a front, essentially continuing to supply its own gas under a different label.

In an interview with Euromaidan Press, Gonchar exposes Moscow’s motives behind this gas transit scheme and warns of its potential to undermine Western sanctions against Russia.

Why some EU countries cling to Russian gas

Citing European sources, Gonchar reveals that the EU is wary of the “Azerbaijani gas” transit idea, recognizing it as a cover for Russian gas.

“A few countries want to continue these relations,” Gonchar explains. “Everything depends on how these countries and Ukraine find a formula for these transit affairs.”

Despite relying on Russia for 98% of its gas, Austria has safeguards against supply disruption, including reverse pipelines and the Baumgarten storage facility. The real issue is price.

“They’re getting gas at a special price,” Gonchar notes. “They’re losing their profit margin, which they’ll never admit publicly.”

Hungary prefers Ukrainian transit for its speed and cost-effectiveness. However, it receives gas through the longer TurkStream pipeline, which routes gas under the Black Sea to Türkiye, then through Bulgaria and Serbia before reaching Hungary. This longer route potentially increases costs.

Slovakia, while technically able to arrange alternative supplies, faces significant challenges:

- Loss of Putin’s discount

- Inability to resell Russian gas to Europe

- Forced domestic price hikes

- Potential political instability for Fico’s government.

These factors explain why Fico, possibly influenced by Russia, is advocating for the “Azerbaijani gas’ scheme.

Unspoken talks continue

On 7 October, Slovak PM Robert Fico met Ukrainian PM Denys Shmyhal in Uzhhorod. While Shmyhal reaffirmed no Gazprom contract extension, the unspoken details are telling.

“Neither Fico nor Shmyhal mentioned Azerbaijani gas. This silence suggests ongoing discussions,” the expert notes.

Two key visits support this theory:

- In August, Oleksii Chernyshov, CEO of Naftogaz (Ukraine’s state-owned oil and gas company), visited Bratislava. His meetings with both his Slovak counterpart and PM Fico elevated the talks to a political level.

- In September, Vojtech Ferenc, CEO of SPP (Slovakia’s state-owned gas company), traveled to Baku. This visit explored the possibility of involving SOCAR, Azerbaijan’s state oil company, in transporting gas through Ukraine.

Ferenc inadvertently revealed a possible plan.

“The simplest way of involving SOCAR would be if it handed back the gas to Gazprom on the Ukraine-Slovak border,” he said in Baku.

These visits, alongside other high-profile trips, point to a complex network of intermediaries. Gonchar believes direct Ukrainian-Russian contact is being avoided.

“The trips of Aliyev to Moscow, Putin to Baku, Fico to Baku and Uzhhorod, Chernyshov to Bratislava, and Ferenc to Baku are not coincidental,” Gonchar suggests. “Russians have chosen intermediaries: Aliyev in Azerbaijan at the eastern end of the pipeline, and Fico at the western end.”

The challenge now lies in balancing the diverse interests of all parties in this high-stakes energy negotiation, with each seeking to maximize their benefit.

Carrots and sticks of gas transit talks

Fico and others are pressuring Ukraine with three main arguments:

- “You need money – this way, you’ll maintain your income”

- “We’ll label Russian gas as Azerbaijani, saving face for you”

- “We supply you with crucial electricity, which you desperately need due to Russian attacks on your power grid.”

Underlying these points is an implicit threat: Slovakia or Hungary could block Ukraine’s EU accession or financial aid.Slovakia or Hungary could block Ukraine’s EU accession or financial aid.

“We understand EU accession isn’t immediate. Hungary currently holds the presidency, but we can wait out their term. There’s no need for hasty decisions to appease Budapest,” Gonchar states.

He remains confident that collaborative efforts between Kyiv, Brussels, and key European capitals can successfully navigate around any obstruction attempts by Fico or Orban, particularly regarding financial aid.

“Azerbaijani” gas transit could weaken sanctions on Russia

Gonchar argues strongly against transiting “Azerbaijani” gas through Ukraine, emphasizing the need to view the situation through a wartime lens.

Key points against the transit:

- Russia would profit far more from gas sales than Ukraine from transit fees, using these funds to finance the war

- Russian gas lobbies, especially in Germany, continue to work quietly for a return to “pragmatic relations.”

Gonchar points to Putin’s speech at the Vladivostok economic forum in early September. Putin noted that despite sabotaging the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic Sea, one of the four lines remained intact, suggesting Germany could still use it.

“They can receive gas through Ukraine and TurkStream but not the Baltic Sea pipeline. It’s schizophrenia, simply nonsense,” he said.

If Ukraine agrees to the “Azerbaijani” gas scheme, it could inadvertently justify the resumption of direct gas trade between Russia and German industries.

“The Germans will say, ‘Look, the EU is getting Russian gas again. Why can’t we use our direct Baltic pipeline?'” Gonchar explains.

This would undermine Ukraine’s push for stronger EU sanctions.

“At the European Council, they’ll ask: why do we need to strengthen sanctions? They’re transporting gas, which means they’re cooperating,” Gonchar concludes.

Navigating caution and corruption in Ukraine’s gas transit dilemma

Gonchar remains cautiously optimistic that Ukraine will resist pressure. He believes the only way Ukraine might be swayed is through corruption – bribing individual officials.

“A corruption fund is being set up,” Gonchar explains. “If pressure fails, they’ll try enticement.”

The recent Lukoil incident exemplifies these complex negotiations. In June, Ukraine halted Russian oil transit to Hungary, adhering to invasion-related sanctions. Budapest quickly proposed a workaround: MOL, a Hungarian company, would purchase Russian oil at the border, allowing it to flow through Ukrainian pipelines under Hungarian ownership.

After three months of negotiations, MOL announced a deal. Curiously, Ukrainian officials remained silent until media scrutiny forced the issue into the open.

PM Shmyhal’s response raised eyebrows: “Today, the Ukrainian government, including me as the Prime Minister, is not involved in negotiations regarding the transit of Russian gas or oil.”

This denial, particularly concerning sanctions-related matters, raises alarming questions about sovereignty and decision-making processes.

Gonchar doubts a similar approach will work for gas transit, citing potential reputational damage to Ukraine’s leadership. He anticipates last-minute developments in gas negotiations, mirroring past disputes.

“Although not many days are left, the decisive things will probably happen in December,” the expert predicts.

Read more:

- Expert warns: “Azerbaijani” gas may mask Russian energy’s EU return

- Why Russia clings to gas lifeline amid Ukraine’s Kursk incursion

- Ukraine to end Russian gas transit deal despite Slovak Prime Minister’s plea

- EU energy ministers weigh options for Russian gas transit as Ukraine transit deal expires

You could close this page. Or you could join our community and help us produce more materials like this.

We keep our reporting open and accessible to everyone because we believe in the power of free information. This is why our small, cost-effective team depends on the support of readers like you to bring deliver timely news, quality analysis, and on-the-ground reports about Russia's war against Ukraine and Ukraine's struggle to build a democratic society.

A little bit goes a long way: for as little as the cost of one cup of coffee a month, you can help build bridges between Ukraine and the rest of the world, plus become a co-creator and vote for topics we should cover next. Become a patron or see other ways to support.