Russia’s propaganda war: How Putin bought Germany

A new report exposes over 130 Russian influence agents active in Germany, even after the Ukraine invasion. Despite Berlin's support for Kyiv, the Kremlin exploits long standing economic ties to manipulate German politics and public opinion.

Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine has dramatically impacted European history, creating unprecedented security and economic challenges.

Moscow laid extensive groundwork for this invasion through years of strategic propagation of pro-Kremlin narratives and the exertion of influence operations to shape public opinion and politics across European states. The calculated use of propaganda and disinformation has been a key element enabling Russia’s current aggression against Ukraine.

Nearly every European country hosts some hierarchy of organized Russian influence, centered on embassy officials and consular staff. These are supported by Russian state agencies like Rossotrudnichestvo, which disseminates regime messaging under the guise of “cultural outreach.” Many Rossotrudnichestvo staff are Russian intelligence officers.

The new “Revealing Russian Influence in Europe” report by the Institute of Innovative Governance analyzes publicly available but dispersed information about Russia’s influencers across European media, digital platforms, political parties, business associations, and lobby groups. In total, the project identified 360 pro-Russian lobbyists in Germany, France, Italy, and Ukraine seeking to undermine sanctions against Russia and support for Kyiv.

Euromaidan Press is publishing a series exposing these lobbyists, beginning with Germany, home to 133 active pro-Kremlin voices across business, media, diasporas, and fringe political movements. Before the invasion, many mainstream German groups also openly backed Moscow.

By highlighting key examples of Russian influence, we aim to show the public the different shapes it takes in European politics and societies, making people more aware and resilient.

Russia’s grip on Germany’s energy sector and politics

Germany’s affinity for Russia spans centuries, initially economic but later cemented by post-WWII guilt over Nazi crimes. Moscow has been seen as a neighbor whose interests Germany should prioritize over Central and Eastern Europe.

Despite current Ukraine support, substantial German political forces oppose fully backing Kyiv and want to limit aid while pushing Ukraine to accept unfavorable peace terms, possibly with Russian endorsement.

In Germany, business interests and far-right “peace” movements drive sympathy for the Kremlin’s stances. Moreover, years of Russian energy sector corruption and funding for German regions may have bred Putin sympathies at the local level, says one of the authors of the “Revealing Russian Influence in Europe” report Oleksiy Nabozhniak.

“Business associations remain an important factor – despite gradually refusing Russian energy, entrepreneurs with Russia ties still have support within bilateral forums, some of which only recently suspended activities,” Nabozhniak told Euromaidan Press.

Russian state giant Gazprom‘s lobbying and infrastructure projects have made Germany dependent on Russian energy exports, enabling political and economic leverage for Moscow. Russia also used approaches from bribing politicians to fostering cultural and educational ties between German and Russian regions, involving officials on both sides.

Former chancellor Gerhard Schröder became a prominent lobbyist for Russia after leaving office in 2005. Members of Germany’s leading parties, the Social Democrats (SPD) and CDU/CSU, had also long promoted closer German-Russian ties.

Central organizations have been the German-Russian Raw Materials Forum and Conference. Gazprom’s German partner VNG (Verbundnetz Gas) was a nexus in these influence networks. Lavish Young Leaders conferences sponsored by Russian and German companies like Gazprom, Porsche, Siemens and others connected 200+ promising employees, especially in gas industries. Momentum continued despite Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

Germany’s business lobby and Russia

German businesses long pushed for close Russia ties, exaggerating Moscow’s economic importance and enabling the Kremlin’s geopolitical goals.

Germany’s Russian gas dependence enabled broader economic links and leverage. Russian state banks like Sberbank aimed to ensnare the German economy by trying to provide loans to vulnerable German companies, like car manufacturer Opel. Russian state corporations “invested” in local regional budget-forming enterprises such as the Wadan shipyard and bankrupt engineering companies.

Cheap Russian gas benefited German exports but compromised European security. German regions took Russian investments, granting Moscow leverage to influence local politicians. Major German corporations like Knauf had key figures like Nikolaus Knauf appointed as honorary Russian consuls. However, after Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine, Germany dismissed these appointees.

Pro-Russian political groups in Germany

Prioritizing Russia in foreign policy had been part of German state doctrine for long, regardless of ruling parties. After February 2022, unequivocal support largely became confined to marginal far-right and far-left groups.

Per research by CeMAS strategy group, more Germans became receptive to Russian propaganda claims over 2022 amid the Ukraine invasion – especially in the formerly Soviet-occupied East German Democratic Republic (GDR) and among far-right AfD and leftist Die Linke voters.

The GDR was ruled as a satellite state under a Moscow-backed communist regime between 1949 until German reunification in 1990, accounting for citizens’ continued cultural and political affinity.

Claims that Ukraine is essentially part of Russia won 24% support in East Germany and 12% in the West. 48% of AfD voters agreed.

In Germany, the Russian diaspora community, especially residents of eastern regions, is now also a substantial political support base for the right-wing AfD party.

“Some AfD leaders with Russian roots exploit alleged discrimination against Russian speakers in Europe, creating civic groups to build an electoral base, in addition to being desired guests on Russian propaganda channels,” says Oleksiy Nabozhniak.

Far-right groups like Free Saxony and civic associations like OstWind, plus leftist “peace movements” like The Alliance for Peace in Brandenburg, reliably amplify Russian and anti-Western disinformation.

Pro-Russian politicians in Germany

Though party leaders officially condemn Russia’s war, Bundestag and EU parliament members from AfD and Die Linke still promote Kremlin narratives.

AfD honorary chairman Alexander Gauland joined Russia’s embassy Victory Day event in Berlin in 2023, blaming Ukraine for dragging Germany into the war with Russia. Die Linke MP Andrej Hunko questions the necessity of supplying weapons to Ukraine. Former Die Linke MP Diether Dehm initiates anti-Ukraine rallies in Munich.

Member of the European Parliament for AfD Gunnar Beck and AfD MP Rainer Rothfuß frequently appear on Russian media pushing propaganda on Europe’s downfall and calling Ukraine a “failed state.” Rothfuß openly backed Russia’s war.

In 2023, AfD parliamentarian Hans-Thomas Tillschneider attended Putin’s economic forum saturated with war propaganda.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Leaked documents from The Washington Post revealed direct Kremlin interference attempts in German politics, pushing for an “anti-war coalition” between Die Linke leader Sahra Wagenknecht, far-left groups, and the far-right AfD to block weapons transfers to Ukraine. Though Wagenknecht declined formal Russian backing after the invasion started, AfD members showed ongoing willingness to collaborate.

Other German far-right politicians like AfD figure Ralph Niemeyer kept visiting Russia post-invasion, meeting Kremlin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, and Alexei Miller, chief executive of Gazprom.

Leaked docs also exposed Russian-devised plans for Reichsbürger protests across Germany under the leadership of the far left or the far right. Further leaks publicized by Der Spiegel reveal Vladimir Sergienko, an AfD Bundestag aide, sought Russian assistance to legally challenge German arms shipments to Ukraine.

A 2022 Texty study analyzing German MPs’ tweets found opposition parties Die Linke and AfD echoed Russian propaganda on Ukraine. Researchers analyzed over 7,000 tweets from 24 February 2022-7 July 2023 mentioning Ukraine. 79% of AfD members with accounts tweeted about Ukraine versus 60% of Die Linke, though Die Linke’s absolute count was higher.

Narratives included opposing weapons to Ukraine, immediate ceasefires favoring Russia, hostility to Ukrainian refugees, blaming Germany’s woes on Kyiv support.

Both parties prioritized “peace talks” along lines of a controversial petition “Peace Manifesto” by Die Linke’s Sahra Wagenknecht and feminist Alice Schwarzer dubbed the “Manifesto of Submission” in German media for arguing Ukraine cannot defeat Russia militarily.

Russian organizations in Germany

At the top of Russia’s political and informational influence networks in Germany besides the embassy, consulates, economic and military attaché, is the representation of Rossotrudnichestvo – federal agency for diaspora ties. Its Russian Center for Science and Culture (“Russian House”) in Berlin has a €10 million budget and remains active.

Unlike elsewhere, in Germany, the coordination of Russian diaspora organizations falls to the local group Russkoe Pole (Russian Field) rather than a Council of Compatriots tied to Rossotrudnichestvo. Russkoe Pole defends Russians from perceived discrimination and “Russophobia.”

Among Russian organizations in Germany, “Cossack” associations are notable, with branches in Hanover, Berlin, Hamburg, Cologne, and elsewhere. These groups claim to embody the spirit of emigrants who fled Russia after the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. They maintain connections with paramilitary “Cossack” organizations in modern Russia and are actively involved in Russia’s war in Ukraine, supported by the Russian Orthodox Church.

The Russian Orthodox Church in Germany, despite formally answering to Moscow Patriarch Kirill, who blessed Russia’s war, avoided echoing his messaging. However, in sending humanitarian aid to the pro-Russian Ukrainian Orthodox Church, claiming persecution by Kyiv, they risked reinforcing Kremlin propaganda narratives.

Pro-Russian rallies in Germany

A distinct aspect of Russian influence in Germany is extensive local engagement in protests supporting Moscow, including marches and motorcades.

“In Germany, numerous ‘peace’ movements, masquerading as pacifists, actually advocate ending financial and military aid to Ukraine to serve Russian interests,” says Oleksiy Nabozhniak.

A January 2023 Reuters expose identified several actors with Russian ties attending a September 2022 Cologne rally against arming Ukraine, including Russian intelligence operatives, Cossacks and immigrants. Key organizers were ex-Russian officer Rostislav Teslyuk, now known as Max Schlund after migrating, and his partner Elena Kolbasnikova.

Other participants eyed were Andrei Kharkovsky, a Germany-based trucker allied with a pro-Moscow Cossack military group, and businessman Oleg Eremenko with past ties to Russian intelligence.

Russian media in Germany

The German-language edition of Russian state broadcaster Russia Today (RT) was launched in 2014 but only aired briefly before being denied access in the EU in 2022. Despite sanctions, RT Deutsch continues releasing propaganda on sites like rt.de targeting German speakers. Researchers claim RT uses “mirror” sites to bypass sanctions, targeting the German-speaking audience specifically.

RT remains a key source of pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian opinions, including former Austrian Chancellor Karin Kneissl (now residing in Russia) and legal advisor to the Die Linke party Alexej Danckwardt. The RT Telegram channel promotes conspiracy theories on German Telegram. The Sputnik news agency also spreads Russian propaganda on TikTok.

Other Russian outlets include the Moscow-funded Russia Beyond Germany promoting Soviet nostalgia, the private project RUssland.RU news agency, and World Economy journal run by Russian political scientist Alexander Sosnovsky.

Former RT employees also run propaganda outlets like Thomas Röper’s Anti-Spiegel blog endorsing Russia’s invasion. Sergey Filbert runs the YouTube channel Voice of Germany spreading Russian lies. Journalist and film director Wilhelm Domke-Schulz appeared in email leaks from the Concord company of the Wagner Group founder Yevgeny Prigozhin, as one of the beneficiaries of Prigozhin’s information campaigns in Germany.

Pro-Russian media in Germany

Many German outlets with ideological or conspiracy-focused leanings side with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Apolut media by Ken Jebsen is featuring pro-Russian authors like Thomas Röper, who label Ukraine as a “Nazi state”.

Compact magazine, led by Jürgen Elsässer, is a mouthpiece for the far-right AfD party. Compact praises Putin’s “new era of politics” and fueles tensions between Poland and Ukraine.

Manova News (formerly Rubikon) spreads narratives about the need for immediate peace talks on Russian terms.

Other outlets like Nachdenkseiten, Junge Welt, Overton Magazin, Zuerst!, also repeat Russian propaganda.

Telegram channels are gaining influence in Germany as a popular “new media” platform that researchers believe cooperates with Russian special services.

Reuters cited the Putin Fanclub Telegram channel run by Wjatscheslaw Seewald, promoting neo-Nazi ideology. After Russia’s invasion, Seewald wrote that “the Reichstag needs to be taken again,” referring to the German parliament.

Russian and pro-Russian media in Germany mostly occupy “alternative” niches without wide influence, says researcher Oleksiy Nabozhniak. The real issue is pro-Russian correspondents from mainstream media.

“Pro-Russian correspondents from mainstream channels, who visit occupied territories of Ukraine without Kyiv’s permission, travel to Russia in search of ‘balance’ and ‘rational explanations’ for what is happening – this is a major unchecked challenge,” says Nabozhniak.

Pro-Russian political experts in Germany

The most popular pro-Russian expert is Alexander Rahr, a German consultant, Gazprom lobbyist and historian. He pushes narratives about Ukraine’s lack of sovereignty, Putin’s inevitability in Russia, and restoring Russia-West economic ties after Ukraine’s defeat.

Beyond direct lobbyists, some German-speaking intellectuals present themselves as objective while spreading pro-Russian disinformation. Daniele Ganser, a Swiss lecturer on Eastern Europe, blames the US for provoking the war in Ukraine. He also questioned Russia’s Bucha war crimes as probable “disinformation.”

Former University of Bonn professor Ulrike Guérot frequently appears on talk shows as a Russia/Ukraine expert despite lacking scholarly publications. She too blames the US for seeking to alienate Russia and the EU, using Ukraine.

Gabriele Krone-Schmalz, a former ARD Moscow correspondent, criticized sanctions against Russia as ineffective.

Russia-friendly organizations in Germany

Longstanding Germany-Russia forums like the German-Russian Forum and Petersburg Dialogue have facilitated relations between officials and business leaders. Russia exploited these to extend influence, with Russian propaganda chief Vyacheslav Nikonov as a leader. After Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, German officials pressed to reduce these forums’ activities.

However, new German pro-Russia advocacy groups have emerged, like the Vadar association led by AfD politicians Ulrich Oehme and Eugen Schmidt. Vadar claims to support Russian Germans and Russian speakers facing “discrimination” due to the war in Ukraine, reinforcing propaganda about oppression of Russians in Europe.

German groups posing as humanitarian, like Zukunft Donbas (Future Donbas), provide assistance to Russian-occupied territories in violation of Ukrainian law. Investigations reveal such groups enable supply chains aiding fascist paramilitaries and even the Russian military behind a charitable façade.

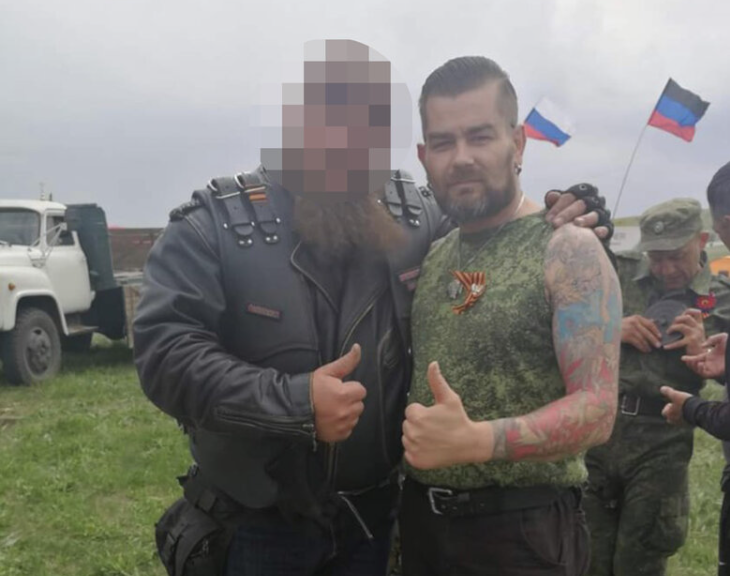

Similarly, Jan Riedel’s German-Russian Souls group participates in pro-Russia events alongside Russian diplomats, laying wreaths for WW2 Soviet soldiers. Riedel also has connections to Russia’s Night Wolves motorcycle club, which promotes Putin’s causes like the annexation of Crimea.

Despite shifting views after Ukraine, past German-Russian ties still resonate. Radical parties like AfD and Die Linke, together polling 30%, echo Russian narratives around peace and protecting Russian speakers, while avoiding outright war support.

“AfD’s election wins, constant ‘rejuvenation’ of its leaders, and outreach to various groups signal the further strengthening of this and similar parties’ positions. Despite publicly condemning Russian aggression, pro-Russian sentiments within these parties – especially among Russian ethnic voters – will only grow,” says researcher Oleksiy Nabozhniak.

Leftist groups and “peace initiatives” aligned with Russia persist, as do pro-Russian rallies, indicating Russia’s investment in “sleeping agent” networks. Though Germany tracks overt sympathizers, propaganda disguises itself amid freedoms of speech and assembly.

Ukraine and the EU must quickly build a broader coalition of allies before the political elite shifts negatively for Kyiv, argues Nabozhniak. They must also convince currently pro-Russian politicians and public figures of finding common ground.

“Fighting Russian propaganda in Europe requires building transparent institutions in Ukraine, as well as promoting counter-narratives about the realities of war, implementing reforms, and encouraging investment,” he says.

However, such long-term approaches often lose priority to less effective instantaneous ones.

Read more:

- Not just Ukraine in focus of Russian propaganda last week, Czechia and Germany in the spotlight too

- Where Putin’s propaganda on Ukraine has worked even better than in Russia: Germany

- Not only Merkel and Schroeder: Germany’s Russia problem runs deep despite war in Ukraine

- Zelenskyy and Scholz sign landmark security pact between Ukraine and Germany