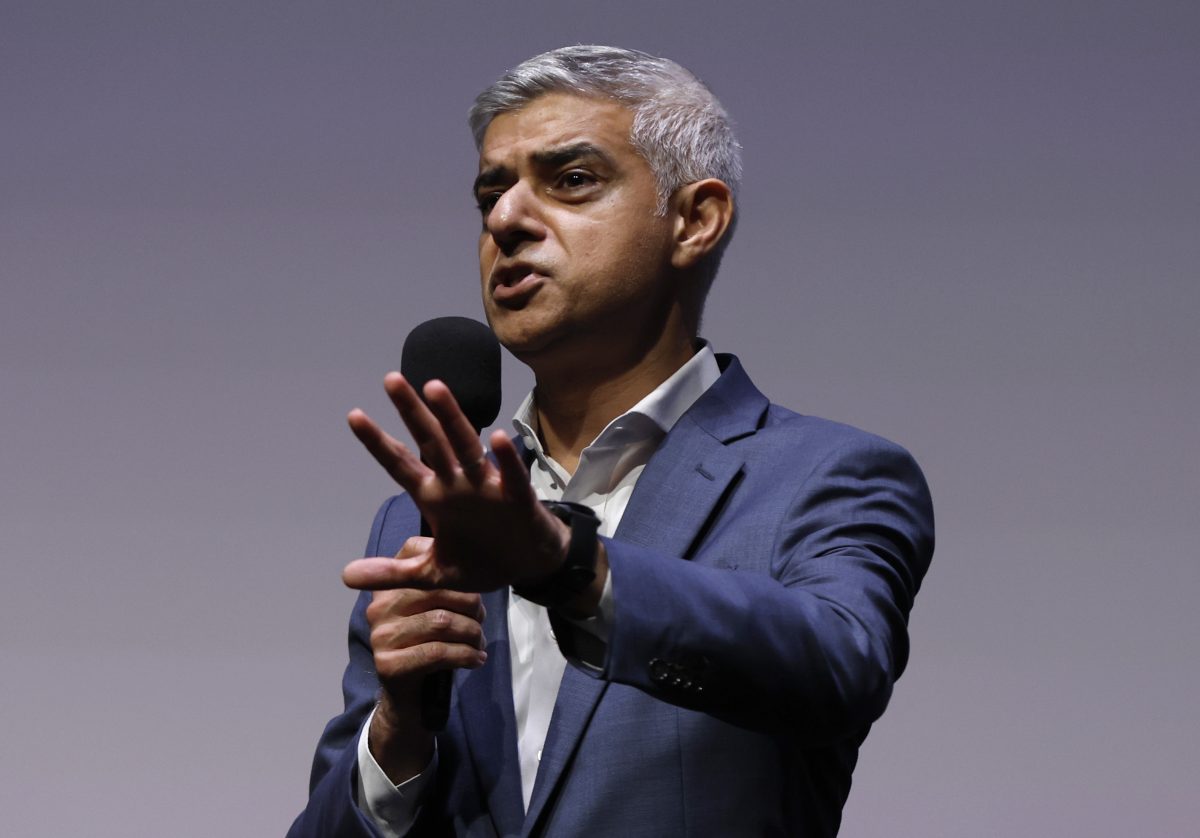

Sadiq Khan’s plan to ‘turbocharge’ London’s economy is wilfully naive

Sadiq Khan’s London Growth Plan is an admirable and ambitious vision for the capital, but its bold projections should be taken with a pinch of salt, says James Ford When running for his historic third term last year, Sadiq Khan claimed to be the “most pro-business Mayor ever”. Now he is putting his money where [...]

Sadiq Khan’s London Growth Plan is an admirable and ambitious vision for the capital, but its bold projections should be taken with a pinch of salt, says James Ford

When running for his historic third term last year, Sadiq Khan claimed to be the “most pro-business Mayor ever”. Now he is putting his money where his mouth is, publishing his London Growth Plan that sets out a bold, ambitious vision for the capital which, the Mayor claims, will “turbocharge” London’s economy to the tune of £107bn over the next decade and create 150,000 jobs. The plan is specific about how it will boost income for both the exchequer (annual tax revenues projected to increase by £27bn) and citizens (an extra £11,000 a year in Londoner’s pockets) by 2035.

The London Growth Plan has much to commend it. It offers much needed policy detail to flesh out one of the Mayor’s biggest manifesto commitments (and address one of London’s most pressing policy challenges – sustained economic growth). The geographical areas, business sectors and economic trends that are projected to be critical to delivering growth – East London, financial services, green growth, and AI – are precisely those that London policy experts would expect. The delivery partners identified as being crucial to making the plan a reality – London Councils, the capital’s public sector and business – are credible and their inclusion is reassuring. Even the acknowledgement that the critical infrastructure to support growth includes not just the obvious ‘big ticket’ items like transport connections and housing capacity but also the all-too-often overlooked essentials like energy, water, waste and digital connectivity will satisfy the most sceptical London policy wonks. So far, so good.

Worrying flaws

But, for all its laudable ambition, there remain some worrying flaws in Sadiq Khan’s London Growth Plan. Firstly, whilst identifying business, local government and London’s public sector as partners should reassure Londoners that this is a serious and credible plan, much rests upon another strategic partner: the UK government. Those involved in London politics always like to talk up London’s exceptionalism – how its higher levels of wealth, education, productivity and foreign investment make it a net contributor to the Exchequer and a major driver of GDP growth above and beyond the performance of other parts of the UK – but the London economy does not exist in a vacuum. The growth plan celebrates how UK economic growth is dependent upon growth in London. However, it overlooks the fact that the London economy will undoubtedly suffer if the national economy contracts. The UK government’s ongoing struggle to deliver meaningfully on its own growth mission should worry City Hall.

The most recent ‘Capital 500’ poll, the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s quarterly economic survey, found that net confidence in their own business performance amongst London firms fell by 14 points (from +29 in Q3 of 2024 to +15 in Q4), marking the lowest figure recorded since 2023. More firms reported a decline in the number of people they employed than said they had expanded their workforce, and the number of firms expecting the UK economy to contract exceeded the number expecting it to grow. According to LCCI CEO Karim Fateh OBE: “While firms are confident about their own prospects, concerns over the broader UK economy persist due to rising costs, disappointing fiscal policies, and ongoing labour shortages.”

Already this year the UK has witnessed flatlining growth, inflation remaining above target, and a fall in business confidence. Morgan Stanley has forecast that the UK’s economic growth would be less than one per cent this year, echoing the estimate of its Wall Street peers Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, citing a slowdown in Britain’s economy and signs of labour market weakness. The firm now expects the UK’s GDP growth to be 0.9 per cent in 2025 (compared to its prior forecast of 1.3 per cent). According to the Evening Standard, unemployment in London is already the highest in the UK. If concerns about the performance of the UK economy were clearly making firms in the capital nervous in the last quarter of 2024 (as the LCCI’s poll found), it is likely that that nervousness has only grown during the first weeks of 2025.

Moreover, the growth plan recognises that the Mayor of London does not currently have control of many of the economic and policy levers required to deliver it. The plan is reliant upon a long-term funding settlement for the capital from central government, new powers to borrow against future growth and fares income to fund transport infrastructure, control over commuter and suburban rail lines, and much closer alignment and co-operation between the national government and the GLA. Many of these have been long-term demands of Sadiq Khan’s and, whilst some of these wishes are likely to be fulfilled, there is no guarantee that all will be or that both the GLA and the UK government will remain united on all elements of this plan for 10 years. Any divergence or disagreement between the two bodies could place the plan’s deliverables or timetable in jeopardy. Past Mayors have, at times, fallen out with central government (often over controversial issues like airport expansion) and a change of leadership or policy direction at either City Hall or in Westminster is very likely before 2035.

Future shocks

Whilst the scope of the London Growth Plan befits London’s importance as a world city, the assumptions underpinning its ambitions do not seem to factor in changes in the global economy any more than they have factored in a declining national economy or deviations between the policy agendas of the Mayor and the Chancellor. There is little evidence (beyond a passing reference on page 30) that the drafting of the growth plan has fully accounted for a second Trump presidency or its decision to adopt a muscular trade policy, swingeing tariffs or an isolationist approach to foreign affairs. The plan recognises the impact that major shocks such as the financial crash, Brexit, Covid-19, and rising energy prices have had on the London economy but does not seem to include any contingency for further shocks. Given the plan supposedly has a shelf-life of ten years, this seems not just optimistic but wilfully naïve.

Maybe the government will give Sadiq Khan the powers and funding required. Maybe the myriad, optimistic, ‘best case scenario’ assumptions that the plan is built upon will come to pass. Maybe the national and global economies will move in sync and in the right direction. And maybe the next decade will see fewer major economic shocks than the previous one. But that is too many maybes for us to take the London Growth Plan at face value and have certainty that it will deliver the results it promises.

Many of the plan’s first year actions require it to be aligned with other statutory policy programmes and strategies, commissioning further studies and research, and undertaking additional scoping and consultation. Hopefully this will answer some of the outstanding questions, fill in any obvious gaps, and generally allow for some of its proposals to be finessed, and for its rougher edges to be smoothed. But, at present, the London Growth Plan feels like a noble, well-intentioned first draft. A good start, but more work is needed.

James Ford is a former policy adviser to Mayor of London Boris Johnson (2010-12) and, before that, to the London Chamber of Commerce & Industry (2004-10).