Story of Ukraine is a Black experience, says African-American reporter

Russia is not only a colonial state, it's a Russian supremacist state, says prominent African American journalist Terrell Starr as he tries to build bridges of trust to Ukraine

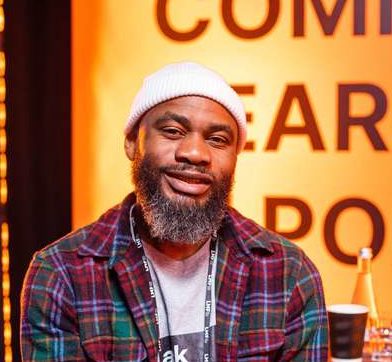

African Americans are some of the most subjected people to disinformation in the USA, yet journalist Terrell Jermain Starr has protected them from Russian propaganda and built a bridge of solidarity to Ukrainians by drawing parallels to the history of discrimination faced by Black people in the USA.

Trained in East European and Eurasian studies, Starr has worked as a Fullbright Fellow in Ukraine and has written for various prominent outlets. From the outset of Russia’s invasion, he has spent most of his time reporting on Ukraine for various Black-owned media, covering the situation on the ground, embedding with territorial defense units, and documenting the flight of refugees.

Speaking at the 10th Lviv Media Forum, Starr said power structures of the USA affect the perception of Ukraine. What follows are fragments of Mr. Starr’s discussion and interview with Euromaidan Press.

“Most people in America who talk about this region were educated in Moscow and St. Petersburg and SAIS, white males who don’t understand oppression in their own country, so how could they understand Ukraine?

I’m an exception, with a master’s in Eastern European and Russian studies. My first experience here was studying Georgian in 2008 when Russia invaded. There’s a nostalgia in America about a progressive Russia that doesn’t exist. That plays a strong role in Ukraine coverage.

My responsibility as an independent journalist was to frame Ukraine in its own context. Much of our media didn’t do this because Ukraine was a low priority in our education system. Power centers power. The imperial and colonial construct of the US affects attitudes towards Ukraine the same way it affects understanding of Black and Latinx communities.”

His work is quintessential for continued American support for Ukraine, as the electoral support of Black Americans is key to the success Democratic candidate Joe Biden, who is expected to be more supportive of helping Ukraine than competitor Donald Trump.

Your stories have impact when the lady at the fish market understands Ukraine

Starr’s told that his answer to building bridges between worlds as distant as Ukraine and the African Americans in America is in building a community through trust: “My audience cares about Ukraine because I care.”

“I knew my stories had an impact when I was at a fish market in Brooklyn. This Jamaican woman came up to me and said, ‘Hey, aren’t you that dude that was in Ukraine? Well, I want to thank you because I understood this country now. I mean, I didn’t know anything before, but now I do.’

This Jamaican lady will never come to Ukraine. But she saw someone, someone who looked like her and someone that she trusted. It all goes around trust, around building community. I felt really happy, that lady at the fish market gave me an indication that I was doing the right thing.”

Ukrainian experience is a Black experience

For Terrell Starr, making the story of Ukraine readable to African Americans is to compare it to their own. He says it’s a very Black experience in many ways.

“When you listen to Putin talk about Ukrainians, he talks about them like they’re white trash. There’s an ethnic slur directed at Ukrainians, we all know what it is [“khokly”].

When Putin talks about Ukraine as not being a real country or people, it is one of the ways that a genocide starts — when you dehumanize people.

I’m aware of the colonial history in Ukraine that goes back hundreds of years. Russia is not only a colonial state, it’s a Russian supremacist state. The Russian has always remained at the top and the Uzbek, the Georgian who are considered the “chorny” [“black”] people, and the Central Asians are always at the bottom. It’s a Russian supremacist framework that’s applied to these regions, including Ukraine.

In America, the way we minimize people by race is a very similar pattern. The way we talked about Ukrainians at the start of this war reminds me of governors, particularly in the South, that use very racist language towards Black Americans. When you draw those parallels and give examples, people can relate because from a human experience, we know that’s bad.”

The challenge of bridging Ukrainians and African Americans

One of the reasons Starr cares about Ukraine stems from his background, coming from a marginalized community, and the solidarity he wants to build with other disadvantaged nations.

“I spent much of my career working in Black-owned media, focusing on Black people. I know what it’s like when my community is marginalized. I took special care because I know no one else would treat my community better, and I vowed to always treat any other community with that same respect.

That’s the responsibility we have – to treat people with the respect we want for ourselves. We can’t be free in our own silos. We have to learn to tell each other’s stories.

In 2014, we had Ferguson and Ukraine had Maidan. That year was the beginning of Ukrainians challenging the West to stop thinking about them as an oblast of Russia.

The big networks and newspapers had their bases in Moscow. They would come to Ukraine and moonlight for a couple weeks, then go on television talking about Ukraine without really knowing much.

The reason people are talking about Ukraine now is because social media empowered individual Ukrainian activists and voices. The West was not going to do it on its own. Ukraine forced it, just as the Black Lives Matter movement was powerful because Black people independently forced mainstream media, which was reluctant, to understand.”

However, bridging the gap between Ukrainians and Black people is not easy, and Mr. Starr often is required to make an effort to reach out to Ukrainians as well.

“Most people lack the capacity to think beyond their own lives and existence. Particularly with Black and Ukrainian people, I do this because it’s a calling that requires patience most don’t have. It’s difficult in both instances.

In Ukraine, most of the time I’m the first Black person most of my Ukrainian friends have a good relationship with. A lot of Ukrainians go to America, study at the best universities, but integrate into whiteness. They go to cities with large Black populations but never meet any Black people, instead hanging out in white spaces. It’s because the real experience of oppression Ukrainians face here is very real, but when they go to America, they integrate into whiteness. It’s not just for Ukrainians, but for anyone considered white.

For Black people, we have a concern about whether these Ukrainians will be supportive of us if we are supportive of them.

Black people need to see other trusted Black people talking about Ukraine. When the war began, I spent half my time on Black media explaining that Western imperialism and colonialism are not the only kinds that exist, pointing to Russian and Chinese imperialism as well. I also use my perspective as a person of faith to talk about the moral responsibility to care about Ukrainians as fellow human beings. It resonates with people.

However, another challenge was when Black people saw the racism Africans faced in Ukraine and Europe when the war broke out. I had to have nuanced conversations explaining what that means.

It’s frustrating being usually the only Black person talking about Black America to Ukrainians. When many travel to the US, they seem to learn the worst of the culture, having one bad experience with a Black person and thinking it applies to all of us, which I think results from racism they don’t realize. I have to patiently talk through it with them and many times they get it. Imagine how difficult it is to be here and be their psychologist about their own bullshit.

But I feel it’s a calling and I enjoy it because I feel it’s making a difference. However, it’s difficult at times because not many people take the time to live in Ukraine and specialize in it.”

Related:

- Georgia’s Foreign Agents law: Russia’s new frontline in its war against freedom in the world

- “Story of a dying empire”: Georgia’s “foreign agent” law protests echo Ukraine’s Euromaidan

You could close this page. Or you could join our community and help us produce more materials like this.

We keep our reporting open and accessible to everyone because we believe in the power of free information. This is why our small, cost-effective team depends on the support of readers like you to bring deliver timely news, quality analysis, and on-the-ground reports about Russia's war against Ukraine and Ukraine's struggle to build a democratic society.

A little bit goes a long way: for as little as the cost of one cup of coffee a month, you can help build bridges between Ukraine and the rest of the world, plus become a co-creator and vote for topics we should cover next. Become a patron or see other ways to support.