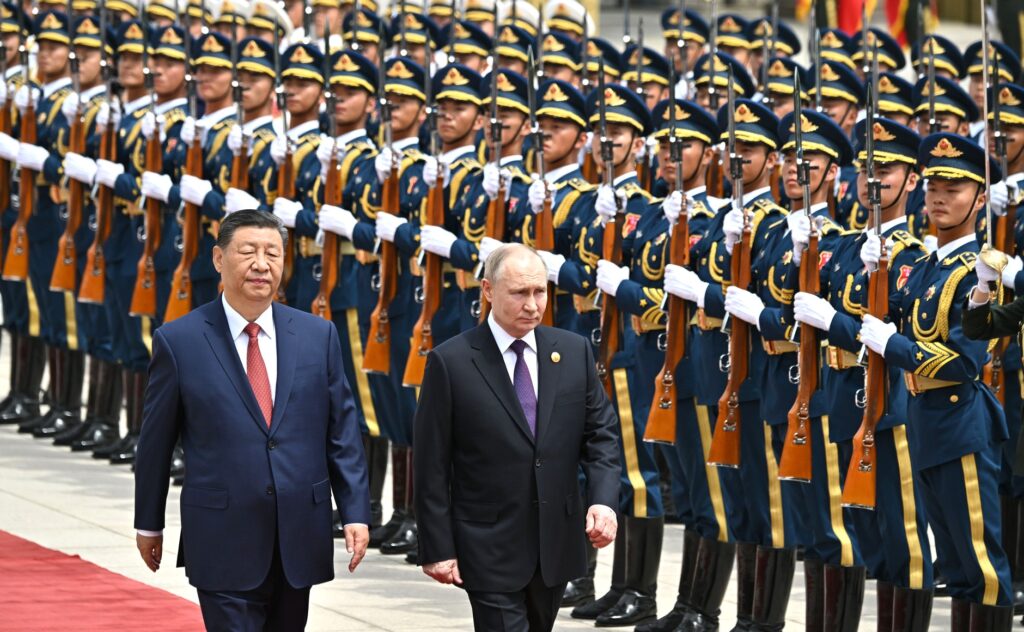

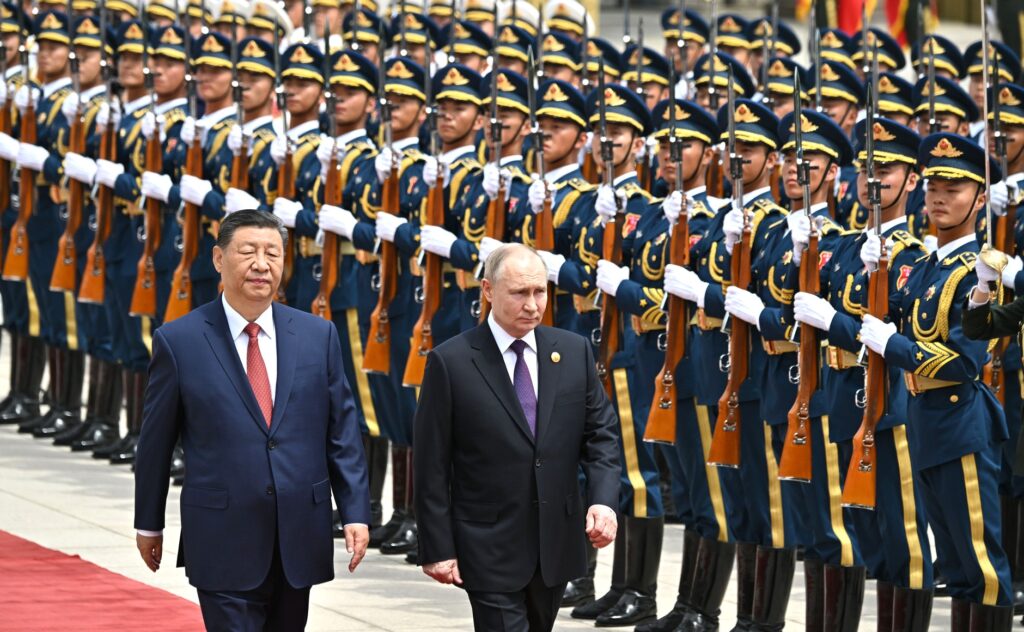

Taiwanese Expert: China became a megaphone for Russia’s lies on Ukraine

The Chinese and Russian propaganda machines work in tandem, amplifying and reinforcing each other, says Taiwanese analyst Min Hsuan Wu. The goal isn't just disinformation: China is prepping for war

Russia’s war against Ukraine isn’t limited to the battlefield. An equally critical information war rages globally, with unexpected players shaping international perceptions.

China, while not directly involved, has emerged as a key influence in this narrative battle. Despite Ukraine being the clear victim of unprovoked aggression, Beijing’s media strategy has achieved a remarkable feat: China is the only country where a majority blames NATO and the US for the conflict, not Russia.

This perspective persists even though Ukraine is not a NATO member.

The impact of these Chinese-Russian media narratives extends beyond China’s borders, subtly influencing public opinion worldwide.

To understand China’s tactics and motivations in this information war, Euromaidan Press spoke with Min Hsuan Wu (nicknamed Ttcat), a Taiwanese activist and CEO of DoubleThinkLab. Wu’s expertise lies in researching Chinese information manipulation and advocating against digital authoritarianism. His organization specializes in analyzing threats to democracy in the digital age and developing counter-strategies.

China’s media echo chamber amplifies Russian narratives

During the first 100 days of the Russia-Ukraine war, a comprehensive DoubleThinkLab monitoring effort revealed Chinese media’s active replication and amplification of Russian narratives. These included false claims about Ukrainian “biolabs” and NATO expansion despite NATO repeatedly declining Ukrainian membership requests since 2008.

Chinese state media also denied the Bucha massacre committed by Russian soldiers and drew misguided parallels between Ukraine’s Azov Battalion and Hong Kong protesters. They manipulated information by misrepresenting Ukrainian President Zelenskyy’s appeals for international support.

“Whenever Zelenskyy called in for more weapons, more help, it would be twisted in the way that the headline of the Chinese news will always be like ‘Zelensky is crying because nobody is helping Ukraine,'” Min Hsuan Wu told Euromaidan Press.

This alignment of Chinese and Russian media narratives stems from a strategic agreement signed around 2015. The agreement facilitates automatic translation and republication of content between the two countries’ state media outlets, creating an “echo chamber” effect.

“Chinese state media pick up what Russian state media’s line is on the war, translate and echo it into the Chinese information space,” Wu explained.

As a result, Chinese journalists can quickly translate and publish Russian stories without additional approval, complicating efforts to trace information to its original source.

China doesn’t really care about Ukraine: It’s all about bashing the West

China’s primary objective in covering the Russia-Ukraine war appears to be criticizing Western countries, particularly the US and NATO.

“They don’t really care about Ukraine. They’re trying to use sympathy for Ukrainians to twist the narrative against the West, saying, ‘These Ukrainians suffer because Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian government have allowed the evil West and NATO,'” Wu explains.

Chinese media, mimicking Russian propaganda, falsely distinguishes between “ordinary Ukrainian people” and the government, overlooking millions of Ukrainians supporting their army. They use the term “Kyiv regime,” echoing Russian media.

Initially, some Chinese intellectuals voiced support for Ukraine, but these dissenting views were quickly censored.

“Their articles were deleted from the whole internet inside of China,” Wu notes.

This media collaboration extends beyond the war, with Russian media generating narratives about Taiwan that Chinese state media then amplify. For instance, a distorted story about Taiwan’s agreement with India on migrant workers was first created by Russian media and then echoed by Chinese outlets.

Interestingly, content glorifying Russian military strength is often not extensively translated. As the war progressed, Chinese experts’ perception of Russian military strength diminished.

“What they want is to attack the US and NATO,” Wu explains.

China’s information operations aim to portray Russia and also China as victims or passive actors. Wu clarifies, “A passive actor who will be provoked somehow into having to take action or to defend itself.”

Why “Russians at War” is pure propaganda, not art

China doesn’t really care about Russia either: It’s all about preparing for war

While China amplifies Russian narratives about Ukraine, its support for Russia is measured. This strategy allows Beijing to benefit economically from Russia’s isolation while avoiding direct confrontation with the West.

“The longer Russia is isolated, the better it is for China economically. Because Russia becomes more reliant on China as a partner,” Wu observes.

Recently, China implemented a direct currency swap mechanism with Russia, enabling yuan-ruble exchanges without intermediary currencies like the US dollar.

According to Wu, China’s actions suggest strategic preparation for a potential conflict over Taiwan, with 2027 mentioned as a possibility by Xi Jinping. China is learning from the Russia-Ukraine war, closely observing Russia’s resilience to sanctions.

“China is observing very closely Russia’s sanctions resilience to learn lessons if there is a conflict in Taiwan, to understand how to insulate its own financial system,” the analyst says.

Additionally, Wu notes that China is gathering military intelligence and analyzing NATO and US weapons systems captured in Ukraine. He also points out China’s status as the world’s largest gold buyer in recent years, interpreting this as strategic: “because they are preparing,” Wu asserts.

China’s media control shapes unique public opinion on the Russia-Ukraine war

China’s media ecosystem is a complex blend of state control and commercial interests. Despite varying types of outlets, state control is pervasive.

“Commercial media are not directly controlled, but if you say something wrong, you’ll receive a call. Or you might find your content deleted or website inaccessible. That’s how you learn what you should and shouldn’t say,” Wu explains.

Publishers receive regularly updated lists of forbidden topics and mandatory content. This tight control results in a unique media landscape.

“China is the only country in the world where a strong majority blames NATO and the US for Russia’s war against Ukraine,” Wu notes. This is despite NATO and the US not directly participating in the conflict and restricting Ukraine’s use of their long-range weapons on Russian territory.

Recent polling data from DoubleThinkLab reveals significant disparities in global perceptions of the war. While countries like Japan, the UK, and Germany largely blame Russia, over 50% of Chinese respondents attribute blame to the US, with NATO as the second most cited culprit.

“They think Russia was forced to start this war because of NATO, and behind NATO, the US. And the Ukrainians are suffering because they’re allegedly just pawns,” the analyst elaborates.

The impact of China’s narrative extends beyond its borders. A DoubleThinkLab poll in Taiwan showed that while most Taiwanese blame Russia for the war, opinions vary significantly among political party supporters. Notably, 46% of Kuomintang (KMT) supporters, a party known for its Chinese identity, blame the US for the conflict.

“They don’t want to live in China. They don’t like Xi Jinping or the Communist Party, but if you ask them, they say, ‘I’m both Chinese and Taiwanese,'” Wu explains.

Taiwan resists China’s propaganda

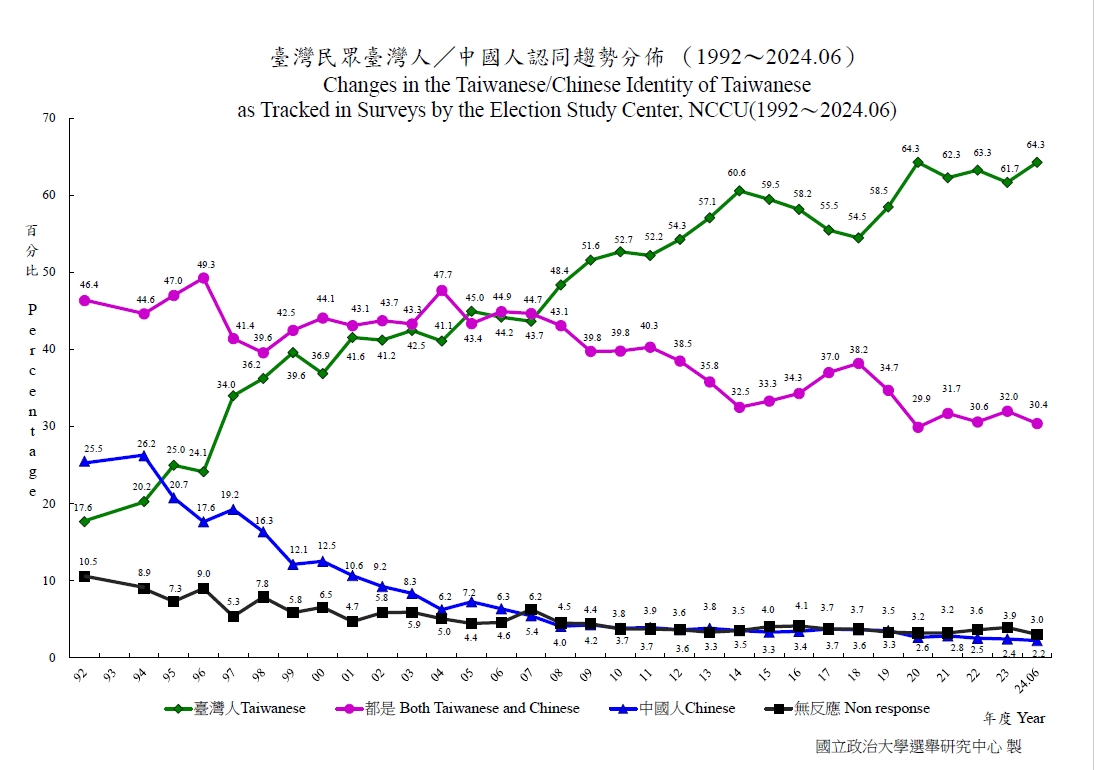

Min Hsuan Wu challenges the common narrative that “Taiwan is part of China” or “free China,” calling it “the biggest disinformation in the world.”

He cites recent data on Taiwanese identity to support his assertion:

- 60% identify as solely Taiwanese

- 32% identify as both Chinese and Taiwanese

- Only 2.4% identify as solely Chinese.

While China’s claim over Taiwan relates to the Kuomintang’s (KMT) retreat after the Chinese Civil War, Wu argues that Taiwan’s distinct identity predates this event. The island has a rich cultural heritage, including indigenous tribes and a unique Taiwanese language with its own literature and scientific works.

This identity faced suppression under Japanese colonization and later KMT rule.

“When KMT came, they felt like, ‘you are all Chinese here. We need to fight back, so we are going to brainwash everyone here, you are not Japanese, you are not Taiwanese, you are all Chinese,’“ Wu explains.

The suppression extended to language: “When my father was a kid… if the other kids spoke Taiwanese, they got punished.”

This policy continued into recent decades, with Taiwanese speakers often stigmatized.

However, Wu notes a shift in the last two decades. “Only now, people are trying to get back our own history, our own language, identity,” he says.

****

China’s sophisticated media strategy has succeeded in shaping a unique narrative about the Ukraine war, not only within its borders but also influencing opinions globally. As Min Hsuan Wu’s research reveals, this approach goes beyond mere propaganda, forming part of a larger geopolitical strategy.

Wu draws unsettling parallels between Russia’s actions in occupied Ukrainian territories and China’s policies toward the Uyghurs.

“I was thinking about cultural genocide occurring in Ukraine with the elimination of language and the abduction of children. I’m very familiar with these repressions from working in China and following what has been happening in Xinjiang for years now,” Wu explains.

He describes disturbing practices in Xinjiang, including forced assimilation and surveillance:

“They will send a Chinese ethnic to every Muslim Uyghur’s home. You have a stranger living inside your house, monitoring you, and even forcing you to marriage. And if you disagree, you are sent to a re-education camp.”

These parallels highlight a broader strategy of identity elimination and cultural assimilation in claimed regions.

The implications of China’s media war extend far beyond Ukraine, potentially reshaping global public opinion on international issues and human rights. As the world grapples with disinformation and cultural suppression, understanding and countering such media strategies becomes crucial for maintaining informed public discourse and protecting vulnerable populations.

Related:

- Russia has become so economically isolated that China could order the end of its war in Ukraine

- The dark truth behind NATO’s “fear of Russian escalation”

- Why Ukraine’s fight is key to defeating Russia-China-North Korea alliance

- Why “Russians at War” is pure propaganda, not art