The Feverish Expectations of Biden’s State of the Union Address

One hundred and eleven years ago, President Woodrow Wilson broke with more than a century of tradition in delivering his annual address to Congress in person, rather than in written form. Thanks to this fateful decision in 1913, the American public must now bear witness each year to the pomp and circumstance of what is known as the president’s State of the Union address.Thursday will mark President Joe Biden’s third such speech before a joint session of Congress, but it’s freighted with additional significance this year because it comes at the beginning of what promises to be a bruising election year. Despite being an official governmental event, this is functionally a hard launch of his reelection campaign—days after what’s shaping up to be an anticlimactic Super Tuesday, eight months before Election Day, and in the looming shadow of a resurgent former President Donald Trump. And Biden, it should be said, is not surging. Amid sinking poll numbers, concerns about his age, and growing concerns about the American role in international conflicts—especially the ongoing war in Gaza that has fiercely splintered his primary electorate—Biden will need to prove to the public that he is still the right man for the job.This task may involve some quick thinking and rapid response, as he will face hostility from the congressional Republicans in the audience. In recent years, the State of the Union—historically an exaggerated exhibition of political theater—has become ever more rowdy, featuring heckling and jeers from the opposing party. In last year’s State of the Union address, Biden challenged Republicans on their support for Social Security and Medicare in the moment, volleying back and forth with jeering GOP members until he received a commitment that Congress would never cut such popular programs.For Biden, the substance of any potential in-the-moment sparring may matter less than the demonstration of energy behind the effort. “He needs to show a degree of vitality that helps answer the questions about his age,” said Matt Bennett, a Democratic strategist and the executive vice president of public affairs at Third Way. “Last year, he was completely in command. He actually owned the House Republicans who were shouting at him—and he was funny, and loose, and he ad-libbed well, and it really worked.”Such a repeat performance would help counter the calcifying narrative about the president’s literal fitness for office. Biden has suffered a slew of negative polls in recent weeks. A Bloomberg News/Morning Consult survey found Trump leading Biden in seven key swing states, and a New York Times poll released this weekend found Trump leading Biden among registered voters 48 percent to 43 percent nationwide. In perhaps worse news for Biden, Americans were far more likely to believe Trump’s policies had helped them personally. Similarly, a new CBS News/YouGov poll found that 67 percent of registered voters rated Biden’s presidency as fair or poor, compared to 53 percent who said the same about Trump.The Biden administration has publicly dismissed the negative polls, pointing out that pollsters often struggle to reach a comprehensive group of voters due to a reliance on landlines. “Polling is broken,” one senior Biden aide told The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos. Even so, Biden never trailed Trump in national polls in 2020. In 2024, it’s become almost commonplace.Widespread concerns among voters about Biden’s age—the president recently turned 81—are generally hurting Biden. The president has recently mixed up the names of foreign leaders, occasionally referring to people who died long ago. A recent report by special counsel Robert Hur on Biden’s handling of classified documents characterized Biden as “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” Both The New York Times and CBS News polls also found a majority of voters are concerned about Biden’s age. (Voters writ large are less worried about Trump, who is in his late seventies and also has a history of verbal slips.)Biden will also have to reconnect with key blocs of Democratic-leaning voters who have recently felt alienated. The president’s unwavering support of Israel in the wake of a military campaign that has killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza has angered many progressives—as well as younger voters, Arab American, and Muslim voters. Biden has called for a six-week cessation of hostilities to allow for the delivery of humanitarian aid and the release of Israeli hostages still held five months after Hamas attacked Israel. He has also urged the Israeli government to minimize civilian casualties. Over the past weekend, the White House authorized aid to be air-dropped into Gaza. Despite these efforts, Biden’s critics maintain that he is not doing enough to pressure Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to stop the displacement and killing of Palestinian civilians.This widespread frustration with Biden was illuminated in the results of the recent Michi

One hundred and eleven years ago, President Woodrow Wilson broke with more than a century of tradition in delivering his annual address to Congress in person, rather than in written form. Thanks to this fateful decision in 1913, the American public must now bear witness each year to the pomp and circumstance of what is known as the president’s State of the Union address.

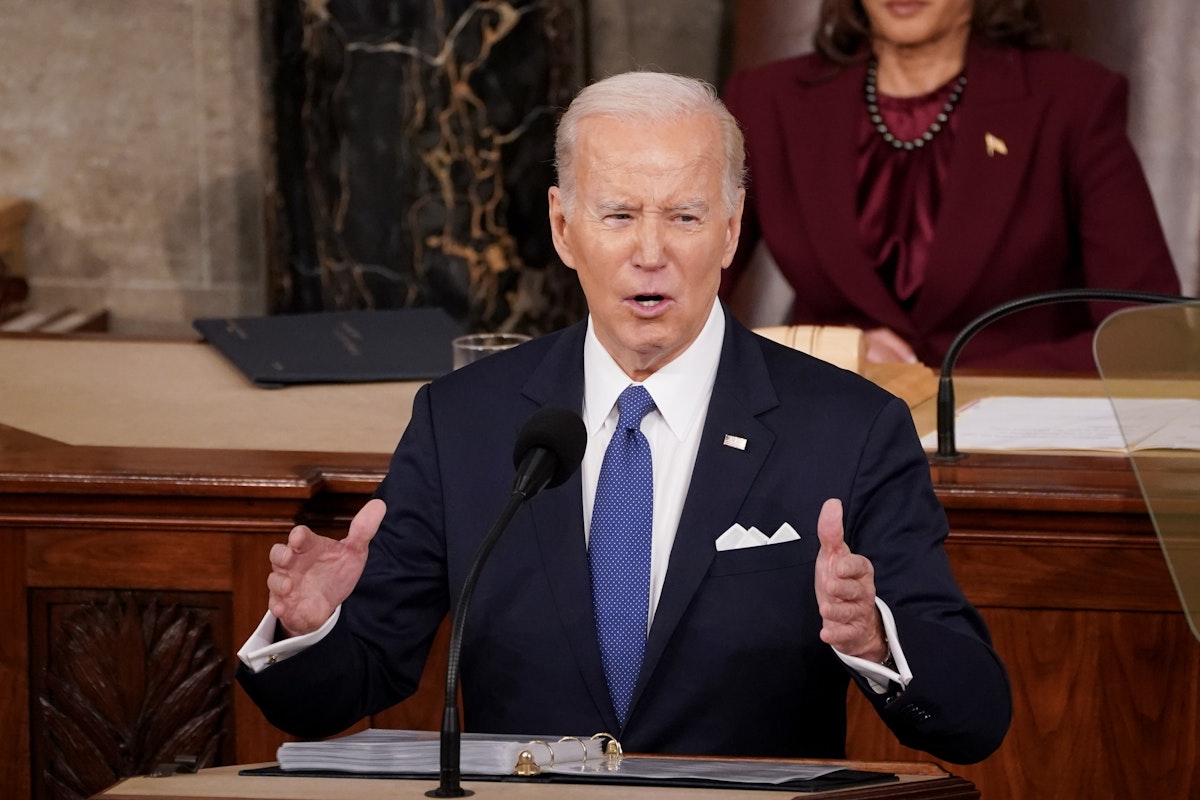

Thursday will mark President Joe Biden’s third such speech before a joint session of Congress, but it’s freighted with additional significance this year because it comes at the beginning of what promises to be a bruising election year. Despite being an official governmental event, this is functionally a hard launch of his reelection campaign—days after what’s shaping up to be an anticlimactic Super Tuesday, eight months before Election Day, and in the looming shadow of a resurgent former President Donald Trump.

And Biden, it should be said, is not surging. Amid sinking poll numbers, concerns about his age, and growing concerns about the American role in international conflicts—especially the ongoing war in Gaza that has fiercely splintered his primary electorate—Biden will need to prove to the public that he is still the right man for the job.

This task may involve some quick thinking and rapid response, as he will face hostility from the congressional Republicans in the audience. In recent years, the State of the Union—historically an exaggerated exhibition of political theater—has become ever more rowdy, featuring heckling and jeers from the opposing party. In last year’s State of the Union address, Biden challenged Republicans on their support for Social Security and Medicare in the moment, volleying back and forth with jeering GOP members until he received a commitment that Congress would never cut such popular programs.

For Biden, the substance of any potential in-the-moment sparring may matter less than the demonstration of energy behind the effort. “He needs to show a degree of vitality that helps answer the questions about his age,” said Matt Bennett, a Democratic strategist and the executive vice president of public affairs at Third Way. “Last year, he was completely in command. He actually owned the House Republicans who were shouting at him—and he was funny, and loose, and he ad-libbed well, and it really worked.”

Such a repeat performance would help counter the calcifying narrative about the president’s literal fitness for office. Biden has suffered a slew of negative polls in recent weeks. A Bloomberg News/Morning Consult survey found Trump leading Biden in seven key swing states, and a New York Times poll released this weekend found Trump leading Biden among registered voters 48 percent to 43 percent nationwide. In perhaps worse news for Biden, Americans were far more likely to believe Trump’s policies had helped them personally. Similarly, a new CBS News/YouGov poll found that 67 percent of registered voters rated Biden’s presidency as fair or poor, compared to 53 percent who said the same about Trump.

The Biden administration has publicly dismissed the negative polls, pointing out that pollsters often struggle to reach a comprehensive group of voters due to a reliance on landlines. “Polling is broken,” one senior Biden aide told The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos. Even so, Biden never trailed Trump in national polls in 2020. In 2024, it’s become almost commonplace.

Widespread concerns among voters about Biden’s age—the president recently turned 81—are generally hurting Biden. The president has recently mixed up the names of foreign leaders, occasionally referring to people who died long ago. A recent report by special counsel Robert Hur on Biden’s handling of classified documents characterized Biden as “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” Both The New York Times and CBS News polls also found a majority of voters are concerned about Biden’s age. (Voters writ large are less worried about Trump, who is in his late seventies and also has a history of verbal slips.)

Biden will also have to reconnect with key blocs of Democratic-leaning voters who have recently felt alienated. The president’s unwavering support of Israel in the wake of a military campaign that has killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza has angered many progressives—as well as younger voters, Arab American, and Muslim voters. Biden has called for a six-week cessation of hostilities to allow for the delivery of humanitarian aid and the release of Israeli hostages still held five months after Hamas attacked Israel. He has also urged the Israeli government to minimize civilian casualties. Over the past weekend, the White House authorized aid to be air-dropped into Gaza. Despite these efforts, Biden’s critics maintain that he is not doing enough to pressure Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to stop the displacement and killing of Palestinian civilians.

This widespread frustration with Biden was illuminated in the results of the recent Michigan primary, in which more than 100,000 Democratic primary voters cast ballots for “uncommitted.” The size of this dissident vote was due in large part to a campaign that urged voters to cast their ballots as “uncommitted” in protest of Biden’s response to the war. Michigan, a critical swing state, has a significant Arab American population. Similar “uncommitted” drives are ongoing in other states.

Moreover, a recent Gallup poll found support for Israel plummeting among young Americans, while a January survey by The Economist/YouGov found that 49 percent of voters aged 18 to 29 believe a genocide is ongoing in Gaza. If Biden wants to win these voters, he will need to convince them he is willing to make changes to the American response to Israel’s actions, said Waleed Shahid, a Democratic strategist who has previously worked with Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“President Biden has deeply fractured the Democratic Party on funding Israel’s war in Gaza, and I think he needs to outline a timetable for the United States to place on Israel [for] not only the war, but to establish Palestinian self-determination,” said Shahid.

Biden also finds himself needing to to walk a fine line on another hot-button issue: immigration policy. Polls demonstrate that voters generally trust Republicans more on issues of immigration and the southern border. Biden has recently taken an increasingly hard line on the topic. He was supportive of a compromise proposal to overhaul border and asylum policy reached by Democratic, independent, and Republican senators, which was then torpedoed by House and Senate Republican leaders, following Trump’s wishes. Biden will likely hammer Republicans for discarding this proposal at the State of the Union, in an attempt to challenge the conventional wisdom that the GOP is tougher on immigration. (This tactic was successfully used by Democrat Tom Suozzi in a House special election last month.)

But Biden will also need to assuage progressive and Hispanic Democratic lawmakers, as well as voters, who have been concerned about recent immigration policy announcements. “Donald Trump and the Republican Party has gone on offense on immigration, [and] President Biden has essentially played defense and catered to Republican talking points on the issue,” said Shahid. “I would like to see President Biden go on offense on that issue, and not just play defense. There needs to be a positive case for immigration reform in this country and reforming asylum laws at the border.”

The president’s State of the Union address will likely hit some familiar beats: bragging about accomplishments and setting the agenda for the future. Biden will also need to make the case that the economy is strong, even as public polling shows middling to poor opinions of how the economy is faring, with particular concerns about inflation. (The president may address the idea of “shrinkflation,” arguing that corporations are increasing prices for fewer goods and services.)

Meanwhile, the issues of abortion rights and reproductive health care continue to be highly salient, particularly in the wake of an Alabama Supreme Court decision last month that temporarily imperiled access to in vitro fertilization. Here the president is on more favorable terrain, and he seems eager to press that advantage: One of Biden’s guests at the State of the Union address will be Kate Cox, a Texas woman who sued the state after she was blocked from obtaining an abortion in the midst of a medical crisis.

But the pure vibes of the State of the Union address will matter just as much as all the boxes the president manages to tick as he winds his way through his speech. Biden will need to be careful, Bennett said, to not allow his speech to devolve into a mere laundry list of his accomplishments and goals while in office: It’s more effective to tell a compelling story to Americans than try to detail specific policies. “People will only take away a vague feeling. They won’t remember all the details,” Bennett said. “What they’ll remember is, how does he make them feel about his own ability and his ability to have an impact on people’s lives?”