The Illiberalism at America’s Core

For much of the twentieth century, the American right was suspiciously absent from historians’ grand narratives of the United States. In the early Cold War, social scientists and political theorists held that the United States was exceptional. Because the United States was not born out of a feudal tradition, Louis Hartz famously argued, the country lacked the extremes of left and right that were found in Western Europe. A liberal consensus bound the nation together, for better or worse. National debate perpetually took place within rigid ideological limits. As the renowned historian Richard Hofstadter observed in The American Political Tradition in 1948, contestants from the major parties “shared a belief in the rights of property, the philosophy of economic individualism, the value of competition.” However fiercely they competed, they “accepted the economic virtues of capitalist culture as necessary qualities of man.”In this view of history, illiberal forces—ranging from xenophobic and antisemitic Populists in the late nineteenth century to a nexus of “Radical Right” anti-communist organizations in the post–World War II period—were characterized as marginal elements that could never withstand the overwhelming power of liberal pluralism. The sociologist Daniel Bell recognized that there was a strain of the electorate that felt “dispossessed” and subscribed to “Protestant fundamentalism … nativism, nationalism.” Yet, as he wrote in 1955, he believed that the “saving glory” of the country was that “politics has always been a pragmatic give-and-take rather than a series of wars-to-the-death.”Over the years, historians have chipped away at the liberal consensus. The baby boom generation of historians, coming out of the tumultuous 1960s, emphasized critiques of liberalism from the left, with bottom-up histories that explored the lives of workers, immigrants, Black and Native Americans, and other groups who had often been left out of earlier work centered on presidents, business leaders, and national elites. Indeed, few historians have done as much as Steven Hahn to trace political resistance from the leftward side of the political spectrum. His landmark book, The Roots of Southern Populism, provided a history of the changing political economy of Up-country Georgia, which fueled the rise of a Southern populism that challenged individualism and free-market principles. In his Pulitzer Prize–winning book, A Nation Under Our Feet, Hahn wrote the history of Black resistance to the different manifestations of white supremacy that took hold in the United States, from fighting against slavery to taking on Jim Crow.And starting in the 1990s, historians of conservatism showed a vibrant right, buckling against the liberal tradition. Kim Phillips-Fein has examined the network of business leaders who directed the mobilization against the New Deal and its legacy. Thomas Sugrue captured the dynamics of the Northern white backlash in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Rick Perlstein’s Before the Storm traced the evolution of the right from the activists who elevated Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater to the top of the Republican ticket in 1964 to Nixonland and Reaganland. Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors deals with the political power of places such as Orange County, California, while Matthew Lassiter and Joseph Crespino focus on Republican appeals to suburban voters just outside cities like Charlotte and Jackson.Yet these new studies of the right mostly left intact the idea that liberalism was the dominant tradition in the United States; they just set out to document how the right fought against it. They primarily wrote about how a grassroots modern conservative movement in the 1970s and 1980s, sometimes earlier, finally broke the hold of the liberal consensus—after the New Left had already shaken it up as a result of Vietnam—and pushed the nation rightward. In his new book, Illiberal America, Hahn aims to tell a different kind of story: one in which illiberalism is not a backlash but a central feature from the founding to today, and in which reaction is an ever-present mode of American political activity.Hahn’s point is not to dismiss liberalism, which he characterizes as an ideology that imagines “rights-bearing individuals,” “civic inclusiveness,” “representative institutions of governance,” “the rule of law and equal standing before it,” democratic “methods of representation,” and the “mediation of power” through “civil and political devices.” His intention, he writes, is to unpack the “shaky foundations on which liberal principles often rested” and “the ability of some social groups to use those principles to define their own communities while refusing it to others.”Hahn defines illiberalism as being founded, like its liberal adversary, on a key set of principles. Illiberalism emphasizes a “suspicion of outsiders” to the community that justifies the “quick resort to expulsion.” In this tradition, the needs of the community triump

For much of the twentieth century, the American right was suspiciously absent from historians’ grand narratives of the United States. In the early Cold War, social scientists and political theorists held that the United States was exceptional. Because the United States was not born out of a feudal tradition, Louis Hartz famously argued, the country lacked the extremes of left and right that were found in Western Europe. A liberal consensus bound the nation together, for better or worse. National debate perpetually took place within rigid ideological limits. As the renowned historian Richard Hofstadter observed in The American Political Tradition in 1948, contestants from the major parties “shared a belief in the rights of property, the philosophy of economic individualism, the value of competition.” However fiercely they competed, they “accepted the economic virtues of capitalist culture as necessary qualities of man.”

In this view of history, illiberal forces—ranging from xenophobic and antisemitic Populists in the late nineteenth century to a nexus of “Radical Right” anti-communist organizations in the post–World War II period—were characterized as marginal elements that could never withstand the overwhelming power of liberal pluralism. The sociologist Daniel Bell recognized that there was a strain of the electorate that felt “dispossessed” and subscribed to “Protestant fundamentalism … nativism, nationalism.” Yet, as he wrote in 1955, he believed that the “saving glory” of the country was that “politics has always been a pragmatic give-and-take rather than a series of wars-to-the-death.”

Over the years, historians have chipped away at the liberal consensus. The baby boom generation of historians, coming out of the tumultuous 1960s, emphasized critiques of liberalism from the left, with bottom-up histories that explored the lives of workers, immigrants, Black and Native Americans, and other groups who had often been left out of earlier work centered on presidents, business leaders, and national elites. Indeed, few historians have done as much as Steven Hahn to trace political resistance from the leftward side of the political spectrum. His landmark book, The Roots of Southern Populism, provided a history of the changing political economy of Up-country Georgia, which fueled the rise of a Southern populism that challenged individualism and free-market principles. In his Pulitzer Prize–winning book, A Nation Under Our Feet, Hahn wrote the history of Black resistance to the different manifestations of white supremacy that took hold in the United States, from fighting against slavery to taking on Jim Crow.

And starting in the 1990s, historians of conservatism showed a vibrant right, buckling against the liberal tradition. Kim Phillips-Fein has examined the network of business leaders who directed the mobilization against the New Deal and its legacy. Thomas Sugrue captured the dynamics of the Northern white backlash in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Rick Perlstein’s Before the Storm traced the evolution of the right from the activists who elevated Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater to the top of the Republican ticket in 1964 to Nixonland and Reaganland. Lisa McGirr’s Suburban Warriors deals with the political power of places such as Orange County, California, while Matthew Lassiter and Joseph Crespino focus on Republican appeals to suburban voters just outside cities like Charlotte and Jackson.

Yet these new studies of the right mostly left intact the idea that liberalism was the dominant tradition in the United States; they just set out to document how the right fought against it. They primarily wrote about how a grassroots modern conservative movement in the 1970s and 1980s, sometimes earlier, finally broke the hold of the liberal consensus—after the New Left had already shaken it up as a result of Vietnam—and pushed the nation rightward. In his new book, Illiberal America, Hahn aims to tell a different kind of story: one in which illiberalism is not a backlash but a central feature from the founding to today, and in which reaction is an ever-present mode of American political activity.

Hahn’s point is not to dismiss liberalism, which he characterizes as an ideology that imagines “rights-bearing individuals,” “civic inclusiveness,” “representative institutions of governance,” “the rule of law and equal standing before it,” democratic “methods of representation,” and the “mediation of power” through “civil and political devices.” His intention, he writes, is to unpack the “shaky foundations on which liberal principles often rested” and “the ability of some social groups to use those principles to define their own communities while refusing it to others.”

Hahn defines illiberalism as being founded, like its liberal adversary, on a key set of principles. Illiberalism emphasizes a “suspicion of outsiders” to the community that justifies the “quick resort to expulsion.” In this tradition, the needs of the community triumph over the individual, and rights are limited to both local geographic spaces and a small number of actions. “Cultural homogeneity” is prized over pluralism and difference, and “enforced coercively.” Illiberal politics demand resistance to some forms of authority—especially to state functions like taxation and regulation—while submitting to others, including religion.

To puncture the architecture of Louis Hartz’s argument, Hahn begins the book by rejecting the assertion that the nation was born without a feudal tradition and was always moving in the direction of enlightened belief. The colonists, Hahn suggests, clearly expressed “neo-feudal” ambitions. He points to the harshness of indentured servitude in the Colonies: In the mid–eighteenth century, most Europeans in the American Colonial countryside were “tenants, laborers, and servants as they lived in states of dependency (wives and children) in the households of property owners.” Between 20 and 30 percent of the workforce in the Virginia and Maryland Colonies were indentured servants, treated as the property of their masters. Corporal punishment was a common way to control workers. The cost for trying to escape usually entailed whipping, lashings, and beatings. Few ever enjoyed the “freedom dues” that were promised when someone finished their contract, because the mortality rate was so high for servants as a result of disease and sheer exhaustion. Of course, the other forced labor pool available to wealthier whites were enslaved Africans who lived under brutal conditions and were stripped of their humanity. Hahn’s disturbing origins story is not just a tale of a people who were “moving toward something more open, more tolerant and more liberally included,” he writes, but also of a country shaped by “neo-feudal dreams, regimes of coerced labor, social hierarchies, and strong cultural and religious allegiances.”

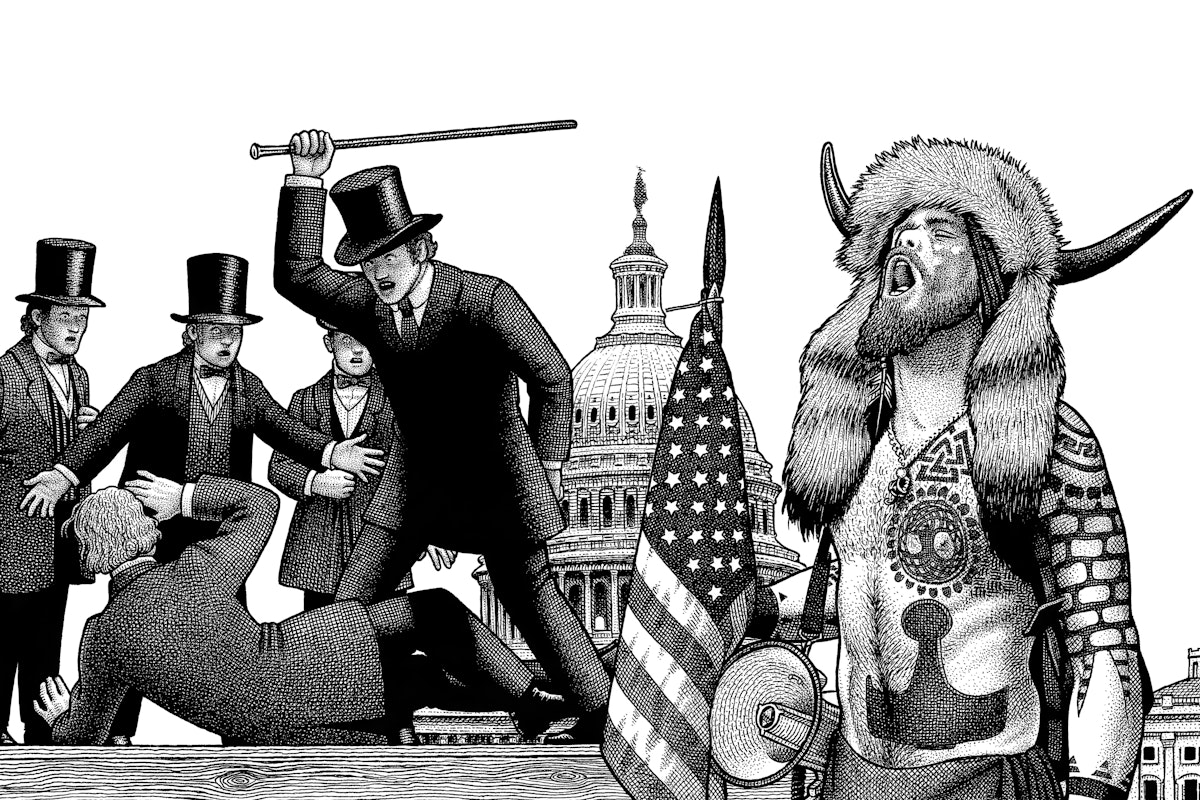

In the 1830s, the era of “Jacksonian Democracy,” illiberalism inspired recurring bouts of white terrorism. Andrew Jackson made his name, Hahn reminds us, not just through the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 but with brutal assaults on the Seminole and Creek Nations, on fugitive slaves, and with the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The 1830s witnessed ferocious assaults on Native Americans, Black Americans, Roman Catholics, and Mormons. This period, Hahn writes, saw “a political culture that thrived on sidearms, street gangs, truncheons, and fists as well as rallies, conventions, and grassroots mobilizations.”

Hahn also emphasizes the intensity of the anti-abolitionist movement: Violence against abolitionist gatherings broke out in big cities like New York and Philadelphia as well as smaller towns such as Concord, New Hampshire. In October 1835, the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was violently heaved with a rope through the streets of Boston by an angry pro-slavery mob. Opponents of freeing slaves burned down the abolitionist meeting site at Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia in May 1838. These events, Hahn argues, were more than vigilante outbursts. “Although some of the rioters came from the lower reaches of the social order, looking to vent their hostilities and dissatisfactions, the leadership came chiefly from the ranks of merchants, bankers, lawyers, and public officials,” many from established, influential families. The “idea of ‘mobs’ and ‘riots,’” Hahn points out, “obscures what was really the persistence of older forms of political expression.”

The atmosphere of illiberal violence even “suffused the halls of legislative power.” Even though Ohio and Illinois outlawed slavery in 1802 and 1848, “Black Laws” curtailed the ability of freed Black men to vote and otherwise participate in civic life. And, building on the work of the historian Joanne Freeman, Hahn recounts how physical altercations became a regular part of democratic and legislative politics at the state and local level. The speaker of the Arkansas House stabbed a colleague to death following a verbal insult in 1837. In 1838, a Maryland congressman named William Graves killed Maine Representative Jonathan Cilley in a rifle duel near the Anacostia bridge in Washington, following accusations of bribery. And, most famously, in 1856 South Carolina’s Preston Brooks pummeled Massachusetts’s Charles Sumner into a bloody pulp on the floor of the United States Senate chamber.

While Hahn joins scholars who explain these clashes as manifestations of the hardening divide over slavery, he paints a broader portrait of a nation where brute force was an endemic element of an illiberal culture; where weapons, street gangs, and militias were a routine way of handling differences and maintaining control. “The arenas of formal electoral politics and of intimidation and expulsion were more interconnected than we might imagine,” he writes.

Illiberalism repeatedly proved its capacity to survive bursts of support for social rights and pluralism. In the post–Civil War period, when the liberal commitment to social rights seemed to be gaining momentum with the end of slavery and the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, dark clouds hovered over Reconstruction. Republicans separated the end of slavery from the guarantee of freedom for African Americans. The convict lease system, founded in the 1840s, was vastly expanded during the Reconstruction period, and carceral repression chipped away at the potential for genuine liberation. Radical Republicans in Congress saw their agenda thwarted by Southern Democrats. The contested election of 1876 was settled when Democrats agreed for Rutherford Hayes instead of Samuel Tilden to become president in exchange for ending Reconstruction. When Jim Crow laws were imposed in the South during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the promise of racial justice ended. In 1921, white mobs destroyed the vibrant Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The lines between liberalism and illiberalism were not always easy to discern. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, illiberalism attached itself to a political movement that was theoretically committed to ameliorating social inequities. The ideas born out of the neo-feudal past were woven into a Progressive reform movement that promised to guide the United States in its transition into the modern era of industrialization and urbanization. While the Progressive era cast expertise and bureaucratization as the means to a more rational and prosperous future, it also produced social engineering, eugenics, and Theodore Roosevelt’s justifications for imperialism.

It wasn’t much of a surprise that Mussolini was admired in many quarters of this so-called liberal nation. By the mid-1920s, the mainstream American press was publishing favorable stories about Il Duce. The American Legion lionized the Italian leader, inviting him to speak at its annual convention in 1923 (he declined). Mussolini, Hahn explains, likewise admired the United States, citing some of the nation’s great authors, such as Emerson and Twain, as inspirations. Adolf Hitler also drew on the United States, from the restrictive immigration laws of the 1920s to the Jim Crow system in the South, in crafting his regime. All of this was not hard to do. There was plenty of good, old-fashioned American illiberalism that they could tap into as they constructed brutal, fascist governments in Italy and Germany. As scholars such as Stefan Kühl and James Q. Whitman have documented in their books The Nazi Connection and Hitler’s American Model, German and American eugenic thinkers with ties to the burgeoning university system shared ideas and funding to promote a science of discrimination and, ultimately, genocide.

Even in the heyday of liberalism and of its left-wing critics in the Age of Aquarius, powerful elected officials embraced illiberalism with gusto. Alabama Governor George Wallace, who ran in 1968 as a third-party candidate for president, embodied the rising forces of postwar reaction. The ultimate practitioner of “grievance politics,” Wallace stitched together a campaign on the far-right American Independent Party ticket, gaining traction through opposition to the civil rights revolution. Whereas a decade ago Wallace’s 1964 and 1968 campaigns were treated by historians as ugly sidebars to the main contests (Goldwater versus LBJ and Humphrey versus Nixon), Hahn brings together the recent literature that has shown how the governor’s racist, reactionary, populist, and often violent appeal tapped into a deep seam that ran throughout working- and middle-class America—from Selma to Detroit. Wallace’s defeat at the ballot box in 1968 should not be confused with a defeat for the ideas he represented. Though on its own Hahn’s argument is not earth-shattering, in the context of the long history of illiberalism, we can see that in many ways it was Wallace rather than his competitors who, as Hahn puts it, “anticipated the country’s political direction” and defined the tenor of conservative politics for decades to come.

Nor was the postwar university immune from illiberal forces. Less famous than the leftist Students for a Democratic Society, though no less influential, was Young Americans for Freedom. Created in 1960, the organization proclaimed to stand against the power of the state and the threat of communism. YAF’s Sharon Statement touted individual freedom, law and order, and federalism. YAF had chapters on campuses all over the country by the time that Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968. The student organization became a starting place for some of the most important conservative figures of the 1970s, such as Pat Buchanan, Richard Viguerie, and Terry Dolan.

Given illiberalism’s deep roots in our political culture, the first few decades of the twenty-first century should not have come as a surprise. When Tea Party activists challenged the legitimacy of the first Black American president and conservative media hosts entertained the “great replacement theory,” they were tapping into some of our oldest national values—though not the ones we like to talk about. Illiberalism was never fringe, as Louis Hartz’s generation believed it to be. Rather, illiberalism inspired law and elected officials, built political movements, and spawned mob action.

Seventy-six years since Richard Hofstadter published The American Political Tradition, Illiberal America mostly succeeds in showing the persistence of reaction, if not its dominance.

What Hahn, and the voluminous scholarship on which his book is built, make clear is that the notion of an inevitable liberal “consensus” that grew organically out of the nation’s founding was wrong. New Hahn, as well as old Hahn, have demonstrated clearly that modern liberalism had to survive in a fraught political culture, one where liberal values were hard to secure and often barely survived. Our national history has been much more layered and complex than Hofstadter’s generation understood. There has been no “American Political Tradition.” There are multiple traditions, each with strong roots in the polity.

Still, the fact that liberalism has been fiercely contested doesn’t mean it has not exerted immense influence. From the Emancipation Proclamation to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, to FDR’s New Deal policies in the 1930s, to LBJ’s Great Society in the 1960s, to President Joe Biden’s ambitious environmental programs since 2021, liberal ideas have thrived, and they have changed the United States.

More important, liberalism has been able to inscribe itself through enduring legislation (think Social Security and Medicare). It was funny but not a surprise that, when Tea Party activists protested President Barack Obama’s health care proposal in 2010, which would have entailed spending cuts in existing programs, they held up placards that read KEEP GOVERNMENT OUT OF MY MEDICARE! Furthermore, grassroots movements from abolitionism, to unionism, to civil rights, to feminism and gay rights have been enormously successful in transforming liberal ideals that were initially dismissed as radical into conventional wisdom. Same-sex marriage now barely causes a stir, whereas back in 1977, orange juice spokeswoman Anita Bryant was able to whip up a storm against an ordinance in Dade County, Florida, that guaranteed civil rights for gay Americans.

And, unlike illiberal tenets, the ideas of liberalism have found much more success at becoming the avowed philosophy of mainstream political leaders. While a Democrat such as President Biden has no problem praising the value of a strong federal government and the protection of civil rights, Republicans until recently have relied on code words when they saw benefit in connecting themselves to illiberalism. As Thomas and Mary Edsall argued in their classic book from the 1990s, Chain Reaction, most leaders in the modern Republican Party relied on dog whistles. Their reluctance to directly invoke these kinds of ideas suggests that in many respects the pull of liberalism has remained stronger.

What Hahn’s provocative synthesis should stimulate is a new look at liberalism itself. We must rethink how we understand the success of a President Franklin Roosevelt or Johnson, given the intensity of the obstacles that they faced. Programs such as Medicare must not be treated as the obvious alternative to bolder social democratic options, or nothing, but as the product of grassroots activists, interest groups, and nonprofits, as well as elected officials. This was the story of the 2020 election, which Biden’s campaign—running on the liberal principles of the rule of law and the importance of democracy—won on the shoulders of everyone who had started to mobilize four years earlier.

As we approach the 2024 election, the potent role of illiberalism in our politics has never been clearer. And, as Hahn demonstrates, upholding liberal values will require, as it long has, a serious and sustained fight.