The Incompetent Bosses Driving American Journalism Into the Ground

Just one month into the year, it looks like 2024 might go down as one of the worst years on record for journalism. The body count alone is staggering: Nearly a quarter of the staff at the Los Angeles Times—at least 115 people—got the ax, as did reporters at Time magazine. The Wall Street Journal reorganized its D.C. bureau, cutting journalists from the masthead and shipping the survivors back to New York; The Washington Post used the new year to throw out another handful of its reporters following a month of historic buyouts; Business Insider got rid of 8 percent of its editorial team; and magazine conglomerate Condé Nast announced it would be letting go of 5 percent of its staff: a whopping 300 employees.Other publications have fizzled out entirely, including some outlets that were once regarded as titans of their genres. Pitchfork, a staple for musicheads everywhere, folded into the creases of GQ; Sports Illustrated, the 70-year-old bible of sports journalism that delighted die-hards and casual readers alike, seemingly threw itself in the garbage on January 22 when its corporate overlords announced that they would be getting rid of every single person on staff; and The Messenger—the Jimmy Finkelstein–led digital publication that only recently launched—abandoned everything it had built in a matter of minutes after Semafor’s Max Tani tweeted that the business was going under. After burning through $50 million, the company’s overlords deleted its Slack channels, shut down the email servers, and pulled the plug on the website mere moments after notifying staff, leaving them with no jobs, no severance, and no clips.Altogether, more than 800 journalists have been laid off in the first four weeks of one of the most consequential election years on record. And if it seems like a movie we’ve seen before, trust your eyes: This round of losses is just the latest in a series of failings from the executives former Deadspin editor in chief Megan Greenwell derided as the “adults in the room.” “An ever-growing number of media owners,” she wrote, “are so exceedingly unwilling to reckon with the particulars of their own business that they refuse to accept our eagerness to help them make money. They’re speaking a language no one else does, proud of their own inability not just to not fail, but to understand the terms on which they’re failing.” From the top down, an increasingly plutocratic layer of decision-makers are placing bad bets, getting wiped out, and leaving their charges holding the bag. It’s now, for all intents and purposes, a civic crisis.While it may appear from the outside that these institutions vanish overnight, behind the scenes they are suffering slowly and in relative silence by a copy-and-pasted strategy employed by executives perched at the very top. At an elementary level, their ideas do not work, and their employees have been trying to get them to listen. In its argument against forecast layoffs at New York Public Radio in September, for example, the radio network’s union pointed to data from a consulting firm, Gartner, outlining how mass sackings in the news media translate to unretrievable profit losses in the not-so-distant future.According to Gartner’s data, the net benefits anticipated by layoffs are offset by key, recurring ingredients that range from the hiring of costly contractors to high employee turnover due to burnout to, eventually, the loss of audience and trust. Lather, rinse, repeat—until your publication’s staff becomes too small, too underpaid, and too exhausted to support your audience’s expectations.Regardless, New York Public Radio decided to cut staff by 6 percent.*What happened at Sports Illustrated is illustrative of this larger trend. The downward shift first became public in 2015, when the outlet’s top brass bent to the trends and fired its staff photographers—the first indication that the photo-laden magazine, like the rest of the print industry, was no longer flush with cash. Then, in 2018, SI fell victim to a media merger of epic proportions. The publication’s parent company, Time Inc. (itself a spinoff of Time Warner) was scooped up by Meredith Corporation for $2.8 billion. The match was short-lived: Meredith felt the three-million-subscriber periodical didn’t fit into its lifestyle brand, so it handed off SI’s intellectual property rights to the brand management company Authentic Brands Group for $110 million the following year.Then began a strange new relationship between corporate titans attempting to cut their own slice of the Sports Illustrated pie. Authentic agreed to whore the magazine’s branding out to the Arena Group, which arranged for a 10-year licensing deal in a $45 million transaction.But among the big leagues, Arena had its own year of commercial uncertainty. In August, 5-Hour Energy billionaire Manoj Bhargava’s Simplify Inventions agreed to purchase roughly 65 percent of Arena—a $50 million deal, though the papers are still pending.Then, in November, Sports

Just one month into the year, it looks like 2024 might go down as one of the worst years on record for journalism. The body count alone is staggering: Nearly a quarter of the staff at the Los Angeles Times—at least 115 people—got the ax, as did reporters at Time magazine. The Wall Street Journal reorganized its D.C. bureau, cutting journalists from the masthead and shipping the survivors back to New York; The Washington Post used the new year to throw out another handful of its reporters following a month of historic buyouts; Business Insider got rid of 8 percent of its editorial team; and magazine conglomerate Condé Nast announced it would be letting go of 5 percent of its staff: a whopping 300 employees.

Other publications have fizzled out entirely, including some outlets that were once regarded as titans of their genres. Pitchfork, a staple for musicheads everywhere, folded into the creases of GQ; Sports Illustrated, the 70-year-old bible of sports journalism that delighted die-hards and casual readers alike, seemingly threw itself in the garbage on January 22 when its corporate overlords announced that they would be getting rid of every single person on staff; and The Messenger—the Jimmy Finkelstein–led digital publication that only recently launched—abandoned everything it had built in a matter of minutes after Semafor’s Max Tani tweeted that the business was going under. After burning through $50 million, the company’s overlords deleted its Slack channels, shut down the email servers, and pulled the plug on the website mere moments after notifying staff, leaving them with no jobs, no severance, and no clips.

Altogether, more than 800 journalists have been laid off in the first four weeks of one of the most consequential election years on record. And if it seems like a movie we’ve seen before, trust your eyes: This round of losses is just the latest in a series of failings from the executives former Deadspin editor in chief Megan Greenwell derided as the “adults in the room.”

“An ever-growing number of media owners,” she wrote, “are so exceedingly unwilling to reckon with the particulars of their own business that they refuse to accept our eagerness to help them make money. They’re speaking a language no one else does, proud of their own inability not just to not fail, but to understand the terms on which they’re failing.”

From the top down, an increasingly plutocratic layer of decision-makers are placing bad bets, getting wiped out, and leaving their charges holding the bag. It’s now, for all intents and purposes, a civic crisis.

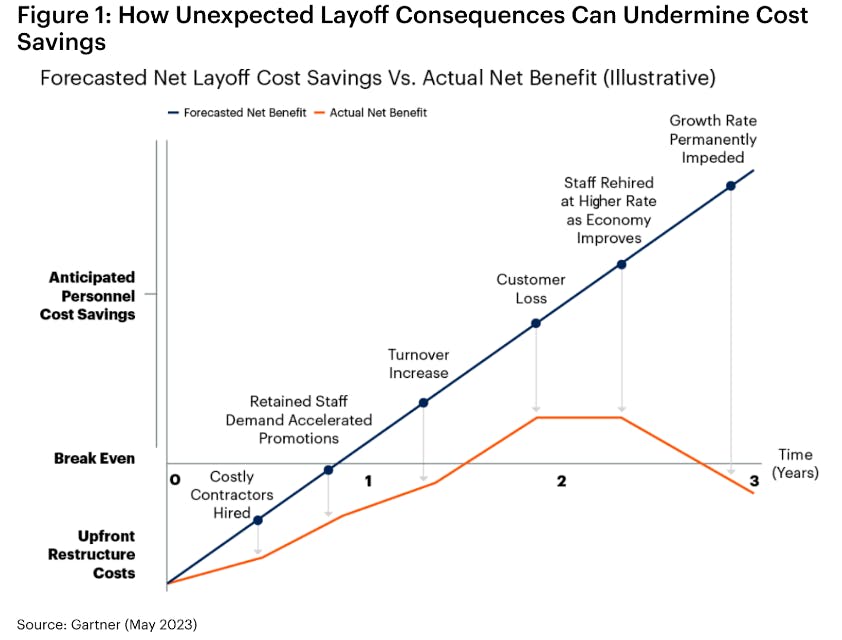

While it may appear from the outside that these institutions vanish overnight, behind the scenes they are suffering slowly and in relative silence by a copy-and-pasted strategy employed by executives perched at the very top. At an elementary level, their ideas do not work, and their employees have been trying to get them to listen. In its argument against forecast layoffs at New York Public Radio in September, for example, the radio network’s union pointed to data from a consulting firm, Gartner, outlining how mass sackings in the news media translate to unretrievable profit losses in the not-so-distant future.

According to Gartner’s data, the net benefits anticipated by layoffs are offset by key, recurring ingredients that range from the hiring of costly contractors to high employee turnover due to burnout to, eventually, the loss of audience and trust. Lather, rinse, repeat—until your publication’s staff becomes too small, too underpaid, and too exhausted to support your audience’s expectations.

Regardless, New York Public Radio decided to cut staff by 6 percent.*

What happened at Sports Illustrated is illustrative of this larger trend. The downward shift first became public in 2015, when the outlet’s top brass bent to the trends and fired its staff photographers—the first indication that the photo-laden magazine, like the rest of the print industry, was no longer flush with cash. Then, in 2018, SI fell victim to a media merger of epic proportions. The publication’s parent company, Time Inc. (itself a spinoff of Time Warner) was scooped up by Meredith Corporation for $2.8 billion. The match was short-lived: Meredith felt the three-million-subscriber periodical didn’t fit into its lifestyle brand, so it handed off SI’s intellectual property rights to the brand management company Authentic Brands Group for $110 million the following year.

Then began a strange new relationship between corporate titans attempting to cut their own slice of the Sports Illustrated pie. Authentic agreed to whore the magazine’s branding out to the Arena Group, which arranged for a 10-year licensing deal in a $45 million transaction.

But among the big leagues, Arena had its own year of commercial uncertainty. In August, 5-Hour Energy billionaire Manoj Bhargava’s Simplify Inventions agreed to purchase roughly 65 percent of Arena—a $50 million deal, though the papers are still pending.

Then, in November, Sports Illustrated was caught utilizing artificial intelligence in a reputation-destroying scandal: Rather than pay journalists for work, the outlet fabricated writers to publish A.I.-generated articles with fake bylines. That scandal led to the ousting of SI and Arena’s CEO, Ross Levinsohn, who blamed the company’s board of directors on his way out.

All these issues came to a head when the most recent wave of layoffs boiled down to a single missed payment and corporate chicanery between SI’s owners, with Arena executives gambling that they could gain more control over the brand from Authentic by withholding payment, reported Axios. They were wrong, but it was the magazine’s staff that lost the bet.

On January 18, Authentic notified Arena Group that it would be revoking its intellectual property rights after Arena missed a quarterly payment of $3.75 million, demanding it now cough up another contractually stipulated $45 million payment. Instead, Arena let go of its staff.

“The actions of this Board and the actions against Sports Illustrated’s storied brand and newsroom are the last straw,” Levinsohn posted on LinkedIn following the announcement of the layoffs. “An incredible team spent years rebuilding great brands like SI through very challenging times. To watch in horror what is transpiring now is one of the most disappointing things I’ve ever witnessed in my professional life.”

Sports Illustrated is far from alone in its tortured narrative. A 2023 analysis by Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism found that by the end of the year, the country will have lost one-third of the papers it had in 2005—a rate of decline much faster than previously predicted—leaving behind more than 200 counties without any local news outlets.

The ever-growing news wasteland is largely the fault of the wave of plutocratic interests that have increasingly clawed their way into the executive suites at major media companies—hedge funds, private equity concerns, and other investment groups. Since the 2008 recession, such groups have gobbled up about half of the industry in order to milk papers for profits, according to a 2021 Financial Times analysis. In recent years, those operators don’t seem to think the noisy business—which is often more about the care and maintenance of important platforms than it is about “innovation”—is worth the headache, increasingly dropping or snuffing out outlets in their entirety, the Medill report notes.

The Washington Post also blamed its recent seismic shrinkage on poor business decisions at the top—mainly stemming from Jeff Bezos’s new hand in its operations, after he’d mostly left the venerable newspaper to its own devices since purchasing it in 2013. “We cannot comprehend how The Post, owned by one of the richest people in the world, has decided to foist the consequences of its incoherent business plan and irresponsibly rapid expansion onto the hardworking people who make this company run,” wrote the leaders of the Washington Post Guild in a statement.

The Messenger’s staff—along with a resounding chorus of other news industry observers—also placed its loss on the shoulders of its billionaire founder, citing Finkelstein’s not-ready-for-prime-time vision, coupled with management so poor that news of the outlet’s executives’ incompetence outperformed the actual product The Messenger was half-heartedly attempting to create. Former employees claimed the company ran the young outlet into the ground in a futile effort to capitalize on trends and hashtags while spending an inordinate amount of money on a pricey high-rise office that its work-from-home employees rarely used.

“You know the facts: No one who knew anything would think you can make money off traffic and hit the dumbass numbers he put out there,” Jim VandeHei, the co-founder of Axios and Politico, told Puck. “I was pissed the moment I heard about this dumb idea. It was business malpractice and human cruelty at an epic scale. Anyone who knew anything about the economics of media knew it would die quickly, spectacularly, and sadly. I am pissed on behalf of the journalists sold snake oil.”

Still, that didn’t stop Finkelstein from attempting to blame the cataclysmic failure, which blew through more than $50 million in runway in a single year on expenses like an $8 million office and a $900,000 salary for its editor in chief, on a tumultuous media market already teeming with layoffs: “The economic headwinds have left many media companies fighting for survival. Unfortunately, as a new company, we encountered even more significant challenges than others and could not survive those headwinds.”

His reporters didn’t buy it, instead opting to file a class action lawsuit against Finkelstein for violating a state statute requiring advance notice for layoffs.

The “owner-with-bottomless-pockets” model of journalism has also stumbled during this period of time. And while billionaires would love to point the blame elsewhere than themselves for the sudden media apocalypse, it’s hard not to notice their recent vigor in scooping up some of the biggest names in the business, especially when many of them arrive at the opportunity with zero prior media experience.

A particularly glaring example of the waste has spilled out on the West Coast. In 2018, biotech billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong took control of the Los Angeles Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune in a $500 million deal from Tribune Publishing, which had run the papers into the ground with “staff reductions, clunky technology and disruptive online ads” that “hampered the paper’s digital progress,” according to the Times. The acquisition earned widespread acclaim as local journalists hoped Soon-Shiong would bring new vitality to the scene. Critically, few seemed to be paying attention to the billionaire’s business practices behind the scenes.

It was here that the once heady fortunes of the L.A. Times suffered a reversal. In 2021, one of the companies in Soon-Shiong’s portfolio, Immunity Bio, lost more than 80 percent of its market cap—approximately $10 billion—in just six short months following a merger with another of the billionaire’s properties, per The Real Deal’s Jerry Sullivan. Despite these staggering losses, the billionaire continued to operate his media properties without any clear plan to bring a profit to the floundering newsrooms.

In July 2023, Soon-Shiong passed The San Diego Union-Tribune to MediaNews Group, a newspaper company owned by hedge fund Alden Global Capital, which so ruthlessly squeezes local papers for every drop of cash that it has been referred to as the “Grim Reaper” and a “destroyer of newspapers.” Soon after acquiring the property, MediaNews Group announced it would be downsizing the newsroom.

That came with matching layoffs at the Times, which saw 70 positions slashed, though those losses were dwarfed by January’s cuts, when more than 20 percent of the company’s staff were given the boot.

In a statement, Soon-Shiong claimed the cuts were necessary because the Times could no longer lose up to $40 million a year without boosting its advertising and subscription revenue, adding that “we have invested almost a billion dollars, underscoring our dedication to preserving its legacy and securing its future,” though he did not specify how he had calculated that figure, according to the paper.

While the future of the paper bows to the will of Soon-Shiong’s pockets, the stakes are clear for his employees. “He’ll still be a billionaire if we tank, but this was the last journalism job some of my coworkers will ever have,” tweeted Los Angeles Times reporter Matt Pearce on Thursday.

Beyond shortsightedness and incompetence, some of the new generation of news oligarchs bring outright hostility to the newsroom. Earlier this month, media magnate David Smith scooped up The Baltimore Sun from Alden Global Capital with high expectations for the 187-year-old newspaper to more closely resemble another one of his media properties—the monopolistic, conservative local media empire Sinclair Broadcast Group.

During a contentious and reportedly insulting two-hour meet and greet between Smith and the paper’s staff, Smith almost exclusively spoke of profits, explaining that although he had only read the daily paper four times and the business was already profitable, he believed he could make it more profitable with some heavy-handed changes. Those include expecting Sun staff to conduct unscientific online polls on a daily basis and veering away from what Smith described as “left wing … meaningless dribble,” before ordering staffers to “go make me some money.”

If there’s any light at the end of this very dark tunnel, it’s that an industry consumed and operated by venal and blundering fat cats is not the only option on the table. Journalism can still thrive when its business model is motivated by stability rather than quick, mass profit.

Several nonprofit models are leading the industry routinely investing in consequential investigative journalism at a time when the scope of so many of their peers seems to be shrinking—including Mother Jones, ProPublica, and The City—the last of which staved off its own bout of potential layoffs in 2023 by giving its employees the option to take a group pay cut. And other emerging media models are earning their own wins: HellGate and Defector have both maintained consistent workflows under an employee-owned framework.

Medill, meanwhile, notes that where hedge funds are evacuating the industry, family-owned companies are stepping in, reclaiming papers that haven’t shuttered—though those operations aren’t nearly as profitable as they were during the 1990s. In the last five years, 164 news startups have launched, with private, non-traded, locally owned outlets maintaining their staff and revenues the best.

On the occasion of The Messenger’s collapse, Defector’s Chris Thompson took stock of the $50 million that Jimmy Finkelstein set on fire and used his own outlet as an example of what’s possible. “Readers of Defector’s annual report will note that operating Defector over its most recent fiscal year cost about $4.4 million,” he wrote, noting that this sum paid for “a 23-person editorial staff and a(n extremely overworked) two-person operations team,” benefits for the full timers, lots of freelance work, and all manner of operating expenses.

“For the low, low price of $22 million, you could have five entire Defectors. That’s at least 115 journalists! Finkelstein could’ve had five entire Defectors for an entire year of operation and still had $28 million in reserve headed into Year 2.” The future of journalism may depend on getting all this dumb money into the hands of smarter people, and getting the lodestone of plutocrats and predators off the backs of the people who actually know how to do the work.

* This article originally included an incorrect figure for the number of layoffs.