The Supreme Court Turns the President Into a King

Five members of the Supreme Court of the United States want to take us back to seventeenth-century absolutism. In a stunning rejection of originalist interpretation, and in defiance of the single statement carved onto the front of the majestic building where they work (“Equal justice under law”), the justices ruled Monday that the president does not have to abide by the laws of the land. They agreed that presidents might be liable for purely private acts, such as Bill Clinton lying about engaging in oral sex in the Oval Office. But in the appropriately titled Trump v. the United States, they have narrowed the scope of possible prosecution so dramatically that in effect Donald Trump cannot be held accountable for almost any of his efforts on January 6, 2021, to retain power beyond his term. The result, as Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in her dissent, is that the court has created a paradigm shift: “The Court has unilaterally altered the balance of power between the three coordinate branches of our Government as it relates to the Rule of Law, aggrandizing power in the Judiciary and the Executive.” The 6–3 majority—five of them in particular—created a ticking time bomb that ignored the Constitution’s most fundamental principles, making it easy for future presidents to become dictators and act with impunity.Last October, special counsel Jack Smith finally indicted Trump on four counts. These included conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to obstruct the counting of Electoral College votes on January 6, actually obstructing the counting of those votes, and preventing the exercise of the fundamental right to vote. For many of us, having watched in horror the events of that day, the counts were long overdue. These counts were modest (no actual counts of treason or seditious conspiracy, for example, even though substantial evidence for both exists), but they were enough that, should he be convicted, Trump faced years in jail. They seemed to promise some accountability for the leader of the coup attempt. They fulfilled what Trump’s own lawyers and Mitch McConnell, at the time the Senate majority leader, had argued during Trump’s second impeachment trial: Trump should not be impeached because the Senate did not provide the proper forum for such judgment. Instead, he was accountable before the regular courts. Brought by a grand jury, the cases were scheduled to be heard before a jury on March 4, 2024. By then, Trump had new lawyers who argued exactly the opposite of his lawyers in the impeachment case: that as president he was above the law. Their theory was that because the “chief executive” under the common law of England before the Revolution had certain privileges and immunities, those must have been retained by the president after the revolution. I worried that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court might believe this ahistorical interpretation. Because I have read so widely in legal treatises of the 1790s, I agreed to compose the first draft of an historians’ amicus brief for the court on this case. With support from the Brennan Center for Justice and a major law firm, I and 14 other historians explained as clearly as possible a central principle of nearly every founding-era legal treatise and the Constitutional Convention, ratifying conventions, and state constitutional conventions. Presidents were not like kings, but accountable to the law like any other citizen. It was both humbling and gratifying during the oral argument, then, when the conservatives on the court avoided addressing historical arguments, even as Justices Jackson, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor quoted from our brief. That any intervention by this court would be de novo was emphasized by Michael Dreeben, who argued the case on behalf of Jack Smith. Halfway through oral arguments in April, Chief Justice Roberts asserted that “the fact of prosecution was enough, enough to take away any official immunity.” Dreeben answered: “I would take issue, Mr. Chief Justice, with the idea of taking away immunity. There is no immunity that is in the Constitution, unless this Court creates it today.” Dreeben could state this so clearly partly because of our brief—and he was absolutely right.In his majority opinion on Monday, Roberts did not disagree with Dreeben. He knew the court was creating a new precedent, and knew that instead of relying on constitutional interpretation, either in terms of text or first principles, they were relying on a few secondary considerations raised by other Supreme Court cases in the recent past. Aside from a few airy references to the Constitution envisioning a “vigorous executive,” Roberts argued that they had to adhere in particular to the 1983 case of Nixon v. Fitzgerald, which they cited dozens of times. But that was a civil case, whereby a former federal employee sought damages against Nixon for firing him. It is an elementary principle of English and American law that civil and criminal law are

Five members of the Supreme Court of the United States want to take us back to seventeenth-century absolutism. In a stunning rejection of originalist interpretation, and in defiance of the single statement carved onto the front of the majestic building where they work (“Equal justice under law”), the justices ruled Monday that the president does not have to abide by the laws of the land. They agreed that presidents might be liable for purely private acts, such as Bill Clinton lying about engaging in oral sex in the Oval Office. But in the appropriately titled Trump v. the United States, they have narrowed the scope of possible prosecution so dramatically that in effect Donald Trump cannot be held accountable for almost any of his efforts on January 6, 2021, to retain power beyond his term. The result, as Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in her dissent, is that the court has created a paradigm shift: “The Court has unilaterally altered the balance of power between the three coordinate branches of our Government as it relates to the Rule of Law, aggrandizing power in the Judiciary and the Executive.” The 6–3 majority—five of them in particular—created a ticking time bomb that ignored the Constitution’s most fundamental principles, making it easy for future presidents to become dictators and act with impunity.

Last October, special counsel Jack Smith finally indicted Trump on four counts. These included conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to obstruct the counting of Electoral College votes on January 6, actually obstructing the counting of those votes, and preventing the exercise of the fundamental right to vote. For many of us, having watched in horror the events of that day, the counts were long overdue. These counts were modest (no actual counts of treason or seditious conspiracy, for example, even though substantial evidence for both exists), but they were enough that, should he be convicted, Trump faced years in jail. They seemed to promise some accountability for the leader of the coup attempt. They fulfilled what Trump’s own lawyers and Mitch McConnell, at the time the Senate majority leader, had argued during Trump’s second impeachment trial: Trump should not be impeached because the Senate did not provide the proper forum for such judgment. Instead, he was accountable before the regular courts. Brought by a grand jury, the cases were scheduled to be heard before a jury on March 4, 2024.

By then, Trump had new lawyers who argued exactly the opposite of his lawyers in the impeachment case: that as president he was above the law. Their theory was that because the “chief executive” under the common law of England before the Revolution had certain privileges and immunities, those must have been retained by the president after the revolution. I worried that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court might believe this ahistorical interpretation. Because I have read so widely in legal treatises of the 1790s, I agreed to compose the first draft of an historians’ amicus brief for the court on this case. With support from the Brennan Center for Justice and a major law firm, I and 14 other historians explained as clearly as possible a central principle of nearly every founding-era legal treatise and the Constitutional Convention, ratifying conventions, and state constitutional conventions. Presidents were not like kings, but accountable to the law like any other citizen. It was both humbling and gratifying during the oral argument, then, when the conservatives on the court avoided addressing historical arguments, even as Justices Jackson, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor quoted from our brief.

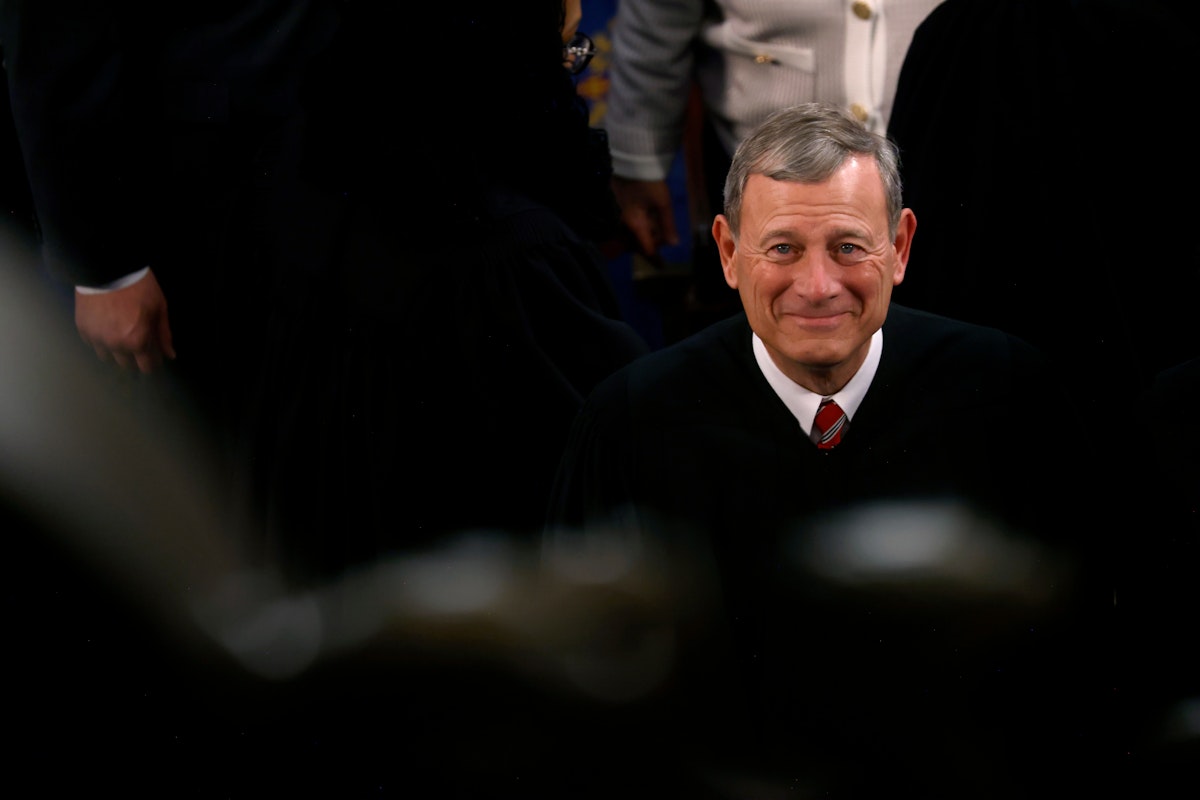

That any intervention by this court would be de novo was emphasized by Michael Dreeben, who argued the case on behalf of Jack Smith. Halfway through oral arguments in April, Chief Justice Roberts asserted that “the fact of prosecution was enough, enough to take away any official immunity.” Dreeben answered: “I would take issue, Mr. Chief Justice, with the idea of taking away immunity. There is no immunity that is in the Constitution, unless this Court creates it today.” Dreeben could state this so clearly partly because of our brief—and he was absolutely right.

In his majority opinion on Monday, Roberts did not disagree with Dreeben. He knew the court was creating a new precedent, and knew that instead of relying on constitutional interpretation, either in terms of text or first principles, they were relying on a few secondary considerations raised by other Supreme Court cases in the recent past. Aside from a few airy references to the Constitution envisioning a “vigorous executive,” Roberts argued that they had to adhere in particular to the 1983 case of Nixon v. Fitzgerald, which they cited dozens of times. But that was a civil case, whereby a former federal employee sought damages against Nixon for firing him. It is an elementary principle of English and American law that civil and criminal law are two entirely separate issues. By stating that they had to adhere to Fitzgerald, and creating a principle for criminal culpability for the president that adhered to the standard set in a case about civil liability, the court’s majority made a completely new ruling. And they did so without discussing any of the relevant historical sources from the founding era; only the dissenting justices did that.

Furthermore, the majority decision created a vast scope of presidential immunity, alleging that presidents should have “presumptive immunity from criminal prosecution for a President’s acts within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility,” by which they mean any acts that might by any conceivable way be understood to be part of his job.

But the scariest parts are in two details. One is that if an act—even one done for criminal purposes—might possibly be deemed official, it cannot be used to prosecute the president for something that might be deemed private, and therefore prosecutable. They deemed that the president’s intention was irrelevant. The second, the one that stunned me, was when they wrote, “Nor may courts deem an action unofficial merely because it allegedly violates a generally applicable law.” Official acts cannot be prosecuted, even when they clearly violate a law, any law. Jackson was correct in her dissent when she wrote that future presidents would be unconstrained. Even a president who “admits to having ordered the assassinations of his political rivals or critics … or one who indisputably instigates an unsuccessful coup … has a fair shot at getting immunity under the majority’s new Presidential accountability model.” It is a “five alarm fire that threatens to consume democratic self-governance.”

The Founders were hardly all wise or all knowing, but they did understand a history that we have now forgotten. There’s a reason that they so carefully included accountability for governors, and presidents, and wanted it for kings. They not only experienced abuses of power at the hands of royal governors, and at the whims of kings, abuses they recounted in the Declaration of Independence. They knew as basic history that this question was at the center of disputes over the actions of unrestrained monarchs during England’s two revolutions in the seventeenth century.

The 1686 case of Godden v. Hales affirmed the power of James II, king of England, to ignore all laws and not be bound by them. Like the decision in Trump v. U.S., the judges could cite no substantial precedent. Before the decision, James II personally interrogated the justices, all of whom held their positions at his pleasure. When it appeared that some of the 12 justices on England’s highest court might not rule as he wished, James II fired them and replaced them with other more amenable justices. After the decision, which cited “the King’s will,” James II’s actions became increasingly egregious, so much so that there was a revolution against him, called the “Glorious Revolution” because his soldiers refused to fight for him. The Convention Parliament that met afterward, in the spring of 1689, requested all of the records from the case be brought to them. They then fired all of the high court justices, levied fines on them, ruled that they could never again hold any office. They also decreed that no high court decisions from the reign of James II could ever be cited as precedent.

Today’s Supreme Court has just recreated one of the most despicable cases in English history, a case that signified the apex of absolutism in British history and was repudiated by a revolution for the damage it caused. Their language about presidents facing no responsibility for criminal actions if they are remotely related to their official responsibilities is substantially the same ruling for Trump that Godden v. Hales was for the king of England in 1686.

As Sotomayor summarized in her dissent: “When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he will now be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune.” She concluded that “in every use of official power,” a power that includes pretty much any part of a president’s official role, “the president is now a king above the law.”

There is still a slim chance for prosecuting Trump for January 6, as the majority allowed that some of the charges, “such as those involving Trump’s interactions with the Vice President, state officials, and certain private parties, and his comments to the general public … present more difficult questions.” But their insistence that Trump’s attempts to pressure Vice President Mike Pence not to certify Joe Biden’s victory involve official conduct and that “Trump is at least presumptively immune from prosecution for such conduct,” will make it nearly impossible for Smith to move forward with any prosecution.

Because impeachment of justices under our Constitution is so difficult, requiring a two-thirds vote in the Senate for conviction, it seems impossible to hold them accountable for a decision that must be expeditiously remedied. But this decision also has persuaded me that President Biden needs to overbalance these wingnuts. He must take advantage of the fact that the number of justices on the court is flexible. He should appoint four new justices who have some integrity, to match the number of district courts (now 13). In the 1790s, when the nation was much smaller, we had six. This partisan court is doing so much to undermine the U.S. government and Constitution, with not only this absolutist decision but their other precedent-destroying decisions of the past weeks and years, that they are inviting a level of chaos that even they don’t have the power to contain—and that’s exactly the kind of environment in which authoritarians like Donald Trump thrive. The Supreme Court has effectively ruled that 250 years of U.S. history under a republic is enough.