The Tragedy of Ryan White

A decade ago, in a graduate seminar on “problems” in the history of medicine, my classmates and I began noticing something we came to call “the AIDS epilogue.” A great many books by historians of public health and medicine, it seemed, ended by invoking a condition that had not previously received much focus in their pages: HIV/AIDS. A pathbreaking book on the spread of germ theory in the early 1900s, for instance, concluded with a discussion of how AIDS “has exposed the worst aspects of our modern-day beliefs about the germ.” A magisterial history of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century tuberculosis similarly ended with the statement that “AIDS, like tuberculosis,” disproportionately burdens the most vulnerable members of society.Often, these epilogues flowed sensibly from the text of the books, and many struck us as understandable stabs at timeliness, at relevance, for scholars in a small, oft-overlooked field. Yet several of my classmates and I feared that, as a trend, the phenomenon of “the AIDS epilogue” risked relegating the study of AIDS to a literal afterthought—isolated, shorn of context, emblematic of the broader marginalization of the study of sexually transmitted infections. Worse, it risked reducing AIDS to the position of mere metaphor, a situation that (as the critic Susan Sontag famously argued) contributes to stigmatization, which itself can have real-world medical consequences.More recently, though, as our distance from the early days of HIV/AIDS has grown, a number of scholars have forcefully wrested the story of AIDS away from the realms of symbol or periphery. From Dan Royles’s history of Black AIDS activists to Karma R. Chávez’s account of efforts at quarantine to Sarah Schulman’s kaleidoscopic study of ACT UP New York, texts drawing on new and innovative archives are rapidly expanding the popular focus beyond the white, gay, cisgender men at the heart of many of the earliest and best-known chronicles of the epidemic—and are relegated to epilogues no longer.The historian Paul M. Renfro’s excellent new book, The Life and Death of Ryan White: AIDS and Inequality in America, does not quite belong to this trend. Instead, it is part of an equally worthy and important revisionist tradition, alongside works like Richard A. McKay’s stunning retelling of the life and death of Gaëtan Dugas, the infamous “Patient Zero.” Such works seek to deconstruct the dominant myths that were made to stand in for a more complete understanding of the epidemic—and reveal what such narratives have long occluded.Renfro, author of a perceptive history of “stranger danger,” is well-situated to take on the sensitive story of Ryan White, an American teenager who—in the mid-1980s—became perhaps the most famous person living with AIDS. White’s biography is one that has been told and retold for decades, from breathless contemporaneous press coverage to a popular made-for-television movie to a superb recent monograph by Ruth Reichard, which explored a broader climate of fear in White’s Indiana community, which was devastated by deindustrialization and environmental harm. Renfro, for his part, reveals how politicians and policymakers seized on the case of Ryan White, AIDS’s first “poster child,” wielding his perceived “innocence” as a cudgel to demonize—and justify their neglect of—those for whom sympathy was less “politically safe.” Which is to say, almost everyone else living with AIDS.Ryan White desperately wanted to be normal. “All I ever wanted to do was to be one of the kids,” he recalled in his co-written autobiography. Yet within days of his birth in December 1971, he was diagnosed with severe hemophilia, a deficiency in the proteins that enable blood to clot. As a consequence of this diagnosis, Ryan couldn’t participate in sports and often spent time at the hospital. Yet his childhood also coincided with the “golden era” of hemophilia treatment; just before he was born, Factor VIII—an effective, at-home treatment for hemophilia—became widely available.Jeanne White-Ginder, Ryan’s mother, considered Factor VIII a miracle drug. But others in the family viewed it with concern. Her father, Ryan’s grandfather, had heard a rumor that Factor VIII—a concentrate derived from the blood of others—might lead Ryan to “catch AIDS.” For Ryan’s childhood also coincided with an explosion of fear surrounding AIDS, a then-incurable syndrome characterized by profound damage to the body’s immune system.True to his grandfather’s fears, Ryan started to feel sick in the summer of 1984; shortly after he turned 13 that December, he was diagnosed with AIDS. Renfro notes that the Food and Drug Administration and blood banking industry had long resisted developing testing or heat-treatment processes that could have prevented the transmission of HIV to those with hemophilia, instead moving to ban blood donations from gay men. Between 1982 and 1984, about half the country’s hemophiliacs contracted HIV.In a matter of weeks, rumors of Ryan’s

A decade ago, in a graduate seminar on “problems” in the history of medicine, my classmates and I began noticing something we came to call “the AIDS epilogue.” A great many books by historians of public health and medicine, it seemed, ended by invoking a condition that had not previously received much focus in their pages: HIV/AIDS. A pathbreaking book on the spread of germ theory in the early 1900s, for instance, concluded with a discussion of how AIDS “has exposed the worst aspects of our modern-day beliefs about the germ.” A magisterial history of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century tuberculosis similarly ended with the statement that “AIDS, like tuberculosis,” disproportionately burdens the most vulnerable members of society.

Often, these epilogues flowed sensibly from the text of the books, and many struck us as understandable stabs at timeliness, at relevance, for scholars in a small, oft-overlooked field. Yet several of my classmates and I feared that, as a trend, the phenomenon of “the AIDS epilogue” risked relegating the study of AIDS to a literal afterthought—isolated, shorn of context, emblematic of the broader marginalization of the study of sexually transmitted infections. Worse, it risked reducing AIDS to the position of mere metaphor, a situation that (as the critic Susan Sontag famously argued) contributes to stigmatization, which itself can have real-world medical consequences.

More recently, though, as our distance from the early days of HIV/AIDS has grown, a number of scholars have forcefully wrested the story of AIDS away from the realms of symbol or periphery. From Dan Royles’s history of Black AIDS activists to Karma R. Chávez’s account of efforts at quarantine to Sarah Schulman’s kaleidoscopic study of ACT UP New York, texts drawing on new and innovative archives are rapidly expanding the popular focus beyond the white, gay, cisgender men at the heart of many of the earliest and best-known chronicles of the epidemic—and are relegated to epilogues no longer.

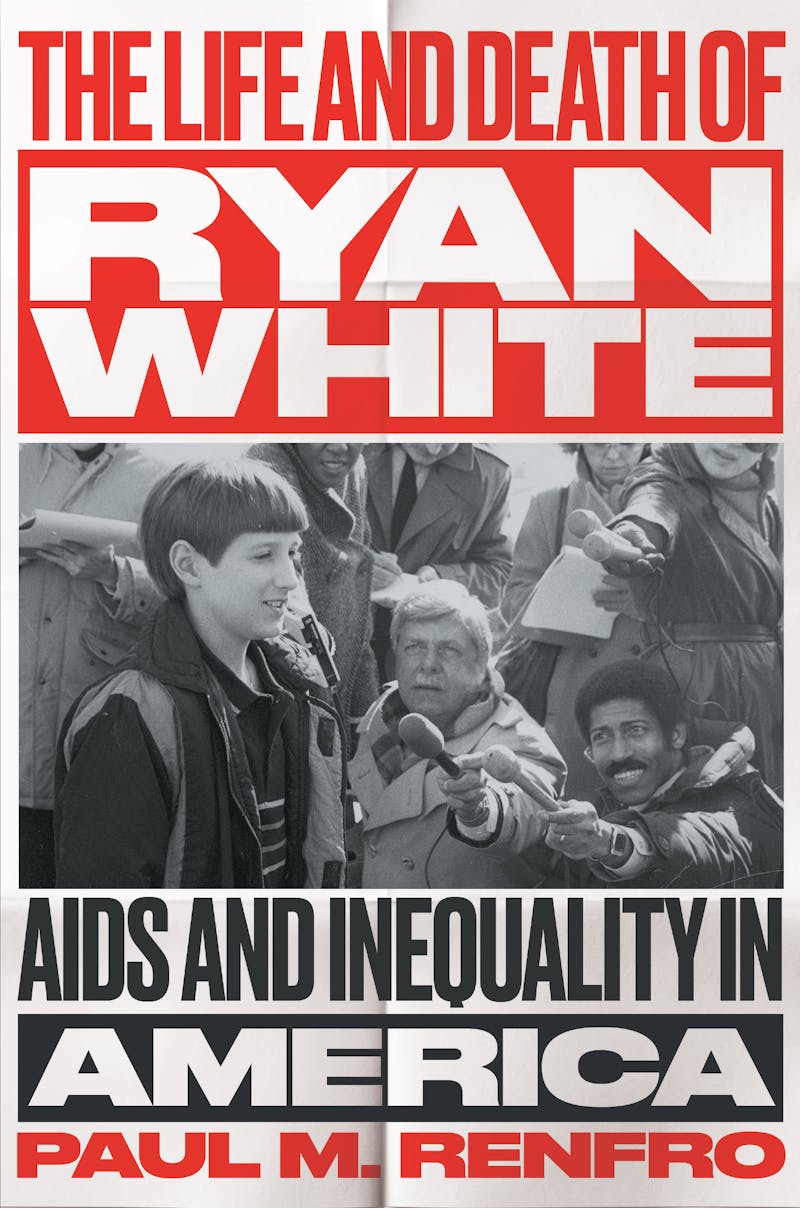

The historian Paul M. Renfro’s excellent new book, The Life and Death of Ryan White: AIDS and Inequality in America, does not quite belong to this trend. Instead, it is part of an equally worthy and important revisionist tradition, alongside works like Richard A. McKay’s stunning retelling of the life and death of Gaëtan Dugas, the infamous “Patient Zero.” Such works seek to deconstruct the dominant myths that were made to stand in for a more complete understanding of the epidemic—and reveal what such narratives have long occluded.

Renfro, author of a perceptive history of “stranger danger,” is well-situated to take on the sensitive story of Ryan White, an American teenager who—in the mid-1980s—became perhaps the most famous person living with AIDS. White’s biography is one that has been told and retold for decades, from breathless contemporaneous press coverage to a popular made-for-television movie to a superb recent monograph by Ruth Reichard, which explored a broader climate of fear in White’s Indiana community, which was devastated by deindustrialization and environmental harm. Renfro, for his part, reveals how politicians and policymakers seized on the case of Ryan White, AIDS’s first “poster child,” wielding his perceived “innocence” as a cudgel to demonize—and justify their neglect of—those for whom sympathy was less “politically safe.” Which is to say, almost everyone else living with AIDS.

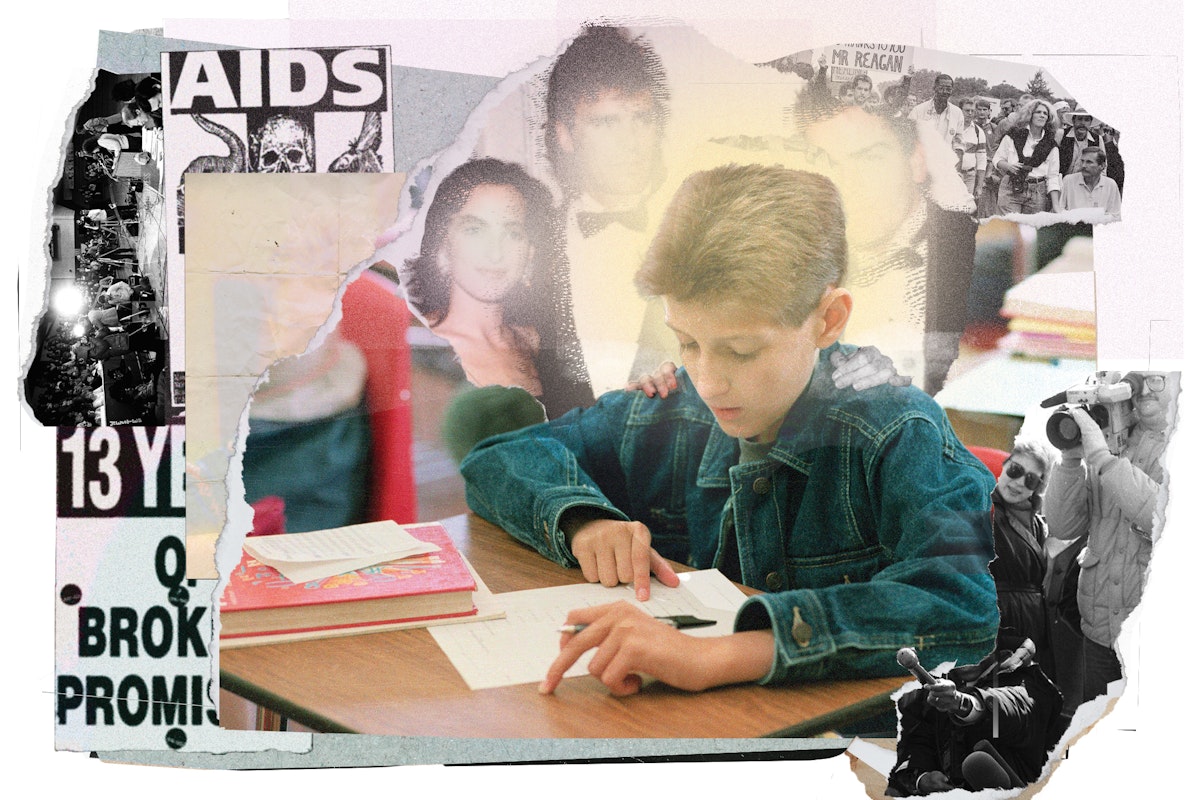

Ryan White desperately wanted to be normal. “All I ever wanted to do was to be one of the kids,” he recalled in his co-written autobiography. Yet within days of his birth in December 1971, he was diagnosed with severe hemophilia, a deficiency in the proteins that enable blood to clot. As a consequence of this diagnosis, Ryan couldn’t participate in sports and often spent time at the hospital. Yet his childhood also coincided with the “golden era” of hemophilia treatment; just before he was born, Factor VIII—an effective, at-home treatment for hemophilia—became widely available.

Jeanne White-Ginder, Ryan’s mother, considered Factor VIII a miracle drug. But others in the family viewed it with concern. Her father, Ryan’s grandfather, had heard a rumor that Factor VIII—a concentrate derived from the blood of others—might lead Ryan to “catch AIDS.” For Ryan’s childhood also coincided with an explosion of fear surrounding AIDS, a then-incurable syndrome characterized by profound damage to the body’s immune system.

True to his grandfather’s fears, Ryan started to feel sick in the summer of 1984; shortly after he turned 13 that December, he was diagnosed with AIDS. Renfro notes that the Food and Drug Administration and blood banking industry had long resisted developing testing or heat-treatment processes that could have prevented the transmission of HIV to those with hemophilia, instead moving to ban blood donations from gay men. Between 1982 and 1984, about half the country’s hemophiliacs contracted HIV.

In a matter of weeks, rumors of Ryan’s diagnosis were racing through his community in Kokomo, Indiana. Ryan was too sick to return to school that year, but by the summer of 1985 he wanted to go back to class, to be “treated like a normal person,” as he later told the press.

On July 30, 1985, J.O. Smith, the superintendent of Ryan’s school district, announced that he would not be allowed to attend school in person; he was a threat to the other students, Smith told the press, and his own safety was at stake. Less than two weeks later, the White family filed suit challenging the decision. Opposing the family was not just the school bureaucracy but also a grassroots group called Concerned Citizens and Parents of Children Attending Western School Corporation, which circulated petitions and held mass meetings to support Ryan’s exclusion.

Out of this conflict emerged a “media firestorm,” Renfro writes, and an unprecedented level of “scrutiny and criticism” descended on this community in north-central Indiana. Amid the front-page stories and prime-time television coverage, Ryan surfaced “as a nearly unassailable figure.” Indeed, within months he had become AIDS’s first “poster child,” the subject of constant press attention, the recipient of gifts from all over the world and, that winter, a happy-birthday telegram from Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

Renfro writes incisively about the speed with which Ryan became a symbol, both “exceptional” and “normal.” Unlike the archetypal person with AIDS (a gay man, an intravenous drug user, a sex worker, etc.), Ryan was white, charismatic, presumed to be straight, and lacking in social or sexual baggage. He was the kind of kid with whom a great many could sympathize. Members of the public, moved by Ryan’s “innocence,” flooded Indiana with letters: “You don’t deserve to have that disease,” a teenager in the Philippines wrote to him. The broader public excoriated the school officials for his exclusion: One suburban resident wrote to superintendent Smith “heartsick over what you’ve done to this boy,” who’d contracted HIV “through no fault of his own.”

Such sentiments served a particular political function: They reduced the crisis to “an issue of personal responsibility, morality, and kindness,” Renfro writes. The exclusion of Ryan White came to be understood as a struggle over whether individuals were willing to treat the sick with compassion, rather than a conflict over public health funding or policy. Noting the popularity of “color-blind” movies of this era (such as Glory and The Long Walk Home), Renfro adds that the narrative surrounding White “reflected a broader late twentieth-century tendency to reckon with injustice on narrow, individualized terms.”

It was easy for many across the country, and those in the press, to blame the “hicks” and “rednecks” in Kokomo; it would have been far more difficult to grapple with how typical the people of Kokomo were for the time. Ryan was far from the only child excluded from school for having AIDS; calls for quarantine and vicious declarations of blame emanated from across the country. Yet retellings of Ryan’s travails reduced the story to a familiar morality tale; the made-for-television movie version even (inaccurately) portrayed some of his antagonistic Indiana neighbors speaking with a Southern twang.

Following months of legal fights, the White family had triumphed in the legal arena, and Ryan was allowed back in school, albeit subject to extreme measures meant to assuage fears. He had to use separate bathroom facilities (“cleaned daily”), eat only with disposable utensils, and his trash would be “double-bagged and incinerated.” Nonetheless, 42 percent of the student body stayed home the day of his return, and some students picketed. Eventually, the parents of more than 20 of his classmates launched a breakaway school in a former American Legion hall. The White family eventually relocated from Kokomo to Cicero, Indiana—a move that many in the media depicted as a neat journey from a community mired in ignorance to one bathed in the light of kindness, despite the two towns’ similarities (both, for instance, had historical links to the Ku Klux Klan).

Ryan died from AIDS-related complications in 1990. His funeral was, again, an exceptional event: Some 1,500 people attended, including first lady Barbara Bush and Michael Jackson; Elton John performed. Renfro contrasts this with the funerals of most of those who died as a result of AIDS: “quiet, poorly attended ceremonies.” The politician and celebrity attendees especially grated on some in the community; one man told an Indianapolis Star columnist, “When have they ever gone to the funeral of a gay person who died of AIDS? Where were they in 1981? Where was Barbara Bush in 1981?”

The explanation for the first lady’s whereabouts was obvious: Ryan may have seemed like the boy next door, but for this reason he was not a “typical” person with AIDS. In fact, Renfro writes, “He was not even a particularly representative child with HIV/AIDS, given the epidemic’s disproportionate impact on Black and Brown youth.” It was Ryan’s very exceptionality and the emphasis on his blamelessness that led members of Congress to affix his name to the Ryan White CARE Act, the emergency HIV/AIDS relief bill they managed to pass in 1990. His name rendered the bill both safe and urgent; one political operative wrote of the legislative strategy, “We needed a superstar. And we found him in Ryan White.” Even the viciously homophobic Senator Jesse Helms recognized the utility of this moniker: “The homosexual lobby of America knew the Ryan White story was too good to pass up,” he told fellow senators. Helms sought to weaponize Ryan’s unique celebrity to his own ends—claiming “innocent victims” like Ryan “would never have contracted AIDS had it not been for the perverted conduct of people who are demanding respectability.” Still, legislators voted overwhelmingly to pass the Ryan White CARE Act.

Yet Renfro damningly shows that the relentless focus of the law’s backers on “sympathetic victims” ended up reinforcing existing prejudices—with devastating consequences. “Once again, Ryan’s ‘innocence’ required the ‘guilt’ of already stigmatized populations,” and, revealingly, few of the law’s champions used the word “gay” when promoting it. The law required states receiving its funding to maintain statutes that criminalize “knowingly” transmitting HIV (in practice, a dangerously vague legal standard) and reinforced a federal ban on funding for needle-exchange programs—provisions that disproportionately harmed marginalized people with AIDS. Today, even as effective medication is available (for those who can afford to pay), the marginalized—especially Black and brown people, queer and trans people, and the poor—continue to constitute an overwhelming and vastly disproportionate share of those living and dying with AIDS.

In his book’s epilogue, Renfro turns to Covid-19. Another era, another public health catastrophe in which those in power sought to individualize suffering and disguise a policy failure as a matter of personal responsibility. Renfro pays particular attention to former Vice President Mike Pence, an avowed homophobe who has invoked his fellow Indianan Ryan White as a symbol of “courage” and how much “we’ve grown in our understanding.” Pence also led the initial White House response to the Covid pandemic, a position from which he fought to displace the government’s duty to protect onto atomized individuals.

It is both predictable and understandable that a public health history published in 2024 would include a “Covid epilogue.” After all, we do not yet have the critical or chronological distance to allow scholars to dissect the pandemic as they no doubt will in years to come. Yet Renfro provides a sparkling example for these future scholars, carefully charting not just the failures of the powerful but also the solidarity of the powerless. He notes that, even as school board officials and many Kokomo neighbors shunned Ryan, Jeanne White-Ginder’s co-workers at the Delco Electronics plant chipped in to cover her son’s medical bills. Such individual acts of charity are insufficient to outmatch the failures of those in charge. But, Renfro concludes, they help us “envision another world.”