The Weaponization of Storytelling

The artist Robert Smithson once offered a definition of entropy involving a sandbox, neatly divided between black sand on one side, white sand on the other. “We take a child and have him run hundreds of times clockwise in the box until the sand gets mixed and begins to turn grey.” If you then ask the child to start running counterclockwise, does the sand go back to where it was? Of course not: “The result,” says Smithson, “will not be a restoration of the original division but a greater degree of grayness and an increase of entropy.” Fighting misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories can feel like being that child running counterclockwise. Spreading info to fight the spread of disinfo can sometimes backfire: True believers double down, and those in the middle sometimes simply throw up their hands claiming they “don’t know who to believe anymore.” Everything is already a mess, but trying to undo the damage can often feel like it just adds more mess—and by the end you’re exhausted from running in circles.Annalee Newitz’s Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind attempts to shift this focus away from simply facts toward, as its title implies, the stories we tell about facts. Newitz begins Stories Are Weapons with Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud and the “father of public relations.” It’s a connection that will be familiar to anyone who knows Adam Curtis’s documentary The Century of the Self, and here Newitz lays out how Bernays “turned his uncle’s project to promote mental health into a system for manipulating people into behaving irrationally.” Most famously, Bernays tried to develop a market for women smokers by tapping into the feminist movement, rebranding cigarettes as “Torches for Freedom” and encouraging women to light up in public. As Newitz explains, it was Bernays’s ability to frame facts and choices around narratives that allowed him to subtly shape consumers’ choices.Bernays walked so that the Defense Department could run. In 1948, Paul Linebarger codified in one place for the first time a number of military strategies for “PSYOPS” (the term isn’t an acronym; as Newitz points out, the military just loves using all caps), in a handbook titled Psychological Warfare. Linebarger, Newitz notes, “was operating in the world that Bernays and Madison Avenue had made,” but was far more interested in whether psychological pressure techniques could be used to advance American interests. Linebarger, a political science professor at Duke University, helped create the Office of War Information, the first permanent branch of the military devoted to psychological warfare, and his short book became, for many in the intelligence business, the “bible on the topic,” as one CIA agent put it. Relying heavily on Bernays’s ideas, Linebarger’s influence led to a form of Cold War psyops that Newitz describes as resembling “an advertising campaign backed up by violence.” If you could convince a foreign populace to like the United States, great; if not, as Linebarger put it, “we gave them alternatives far worse than liking us, so that they became peaceful.”Perhaps the most interesting element that Newitz unearths about Linebarger is how much of his written output was not military guidebooks but rather fiction. Under the pseudonym Felix C. Forrest, Linebarger wrote literary fiction, and as Carmichael Smith, he wrote a Cold War spy novel. But it was as Cordwainer Smith that he became most well known, writing dozens of now-canonical science fiction stories. Further, Newitz notes, “Linebarger wasn’t the only sci-fi author who worked in intelligence, nor was he even the first”: The writer Rose Macaulay worked in the British propaganda department during World War I; Alice Sheldon wrote under the name James Tiptree Jr. while working as a CIA analyst; Larry Niven consulted for the Department of Defense, as did John Campbell. (While L. Ron Hubbard never worked for the government, one could add him to this list of those who wrote fiction and were also interested in psychological persuasion.) It’s this sensitivity to the world of narrative and imagination, Newitz suggests, that helped these writers to excel in the world of spycraft and psychological manipulation. Newitz themself is also a writer of three well-reviewed novels of speculative fiction, so their interest and sensitivity to this overlap makes a great deal of sense. In order to foster a world less riven by disinfo and psychological warfare, we need to better understand how these tools are embedded in narratives that get used to shape our world. “To achieve psychological disarmament,” Newitz writes in the introduction, “we’ll need to rethink the role of stories in our lives—and, more importantly, to change the way we act on the stories we hear.”While it by no means shies away from the darker aspects of American culture and the hard realities we’re facing, Stories Are Weapons is more than just another slog through a dark and dreary

The artist Robert Smithson once offered a definition of entropy involving a sandbox, neatly divided between black sand on one side, white sand on the other. “We take a child and have him run hundreds of times clockwise in the box until the sand gets mixed and begins to turn grey.” If you then ask the child to start running counterclockwise, does the sand go back to where it was? Of course not: “The result,” says Smithson, “will not be a restoration of the original division but a greater degree of grayness and an increase of entropy.”

Fighting misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories can feel like being that child running counterclockwise. Spreading info to fight the spread of disinfo can sometimes backfire: True believers double down, and those in the middle sometimes simply throw up their hands claiming they “don’t know who to believe anymore.” Everything is already a mess, but trying to undo the damage can often feel like it just adds more mess—and by the end you’re exhausted from running in circles.

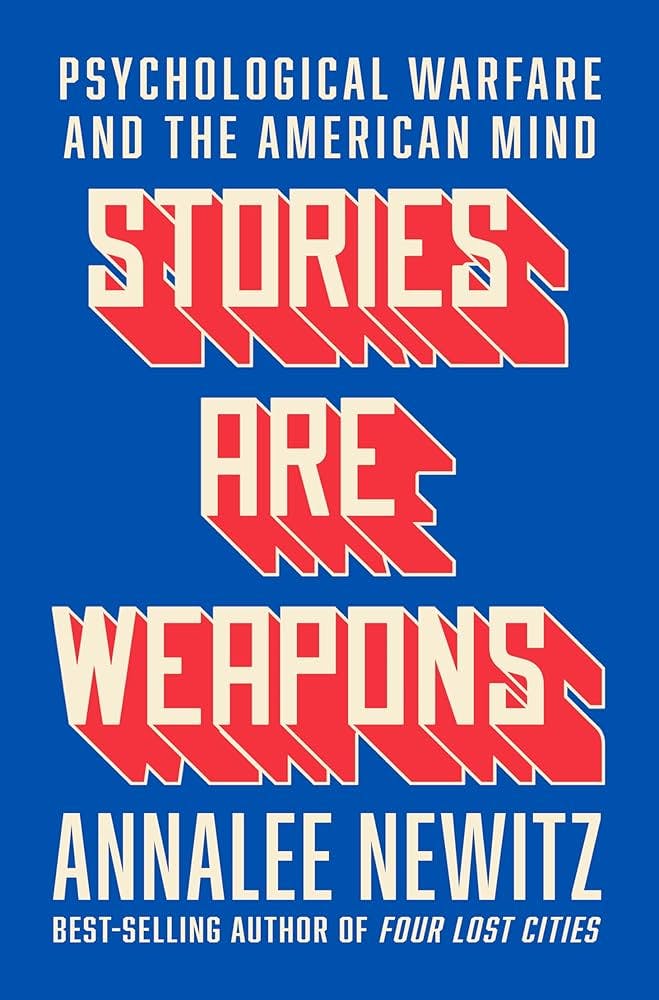

Annalee Newitz’s Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind attempts to shift this focus away from simply facts toward, as its title implies, the stories we tell about facts. Newitz begins Stories Are Weapons with Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud and the “father of public relations.” It’s a connection that will be familiar to anyone who knows Adam Curtis’s documentary The Century of the Self, and here Newitz lays out how Bernays “turned his uncle’s project to promote mental health into a system for manipulating people into behaving irrationally.” Most famously, Bernays tried to develop a market for women smokers by tapping into the feminist movement, rebranding cigarettes as “Torches for Freedom” and encouraging women to light up in public. As Newitz explains, it was Bernays’s ability to frame facts and choices around narratives that allowed him to subtly shape consumers’ choices.

Bernays walked so that the Defense Department could run. In 1948, Paul Linebarger codified in one place for the first time a number of military strategies for “PSYOPS” (the term isn’t an acronym; as Newitz points out, the military just loves using all caps), in a handbook titled Psychological Warfare. Linebarger, Newitz notes, “was operating in the world that Bernays and Madison Avenue had made,” but was far more interested in whether psychological pressure techniques could be used to advance American interests. Linebarger, a political science professor at Duke University, helped create the Office of War Information, the first permanent branch of the military devoted to psychological warfare, and his short book became, for many in the intelligence business, the “bible on the topic,” as one CIA agent put it. Relying heavily on Bernays’s ideas, Linebarger’s influence led to a form of Cold War psyops that Newitz describes as resembling “an advertising campaign backed up by violence.” If you could convince a foreign populace to like the United States, great; if not, as Linebarger put it, “we gave them alternatives far worse than liking us, so that they became peaceful.”

Perhaps the most interesting element that Newitz unearths about Linebarger is how much of his written output was not military guidebooks but rather fiction. Under the pseudonym Felix C. Forrest, Linebarger wrote literary fiction, and as Carmichael Smith, he wrote a Cold War spy novel. But it was as Cordwainer Smith that he became most well known, writing dozens of now-canonical science fiction stories. Further, Newitz notes, “Linebarger wasn’t the only sci-fi author who worked in intelligence, nor was he even the first”: The writer Rose Macaulay worked in the British propaganda department during World War I; Alice Sheldon wrote under the name James Tiptree Jr. while working as a CIA analyst; Larry Niven consulted for the Department of Defense, as did John Campbell. (While L. Ron Hubbard never worked for the government, one could add him to this list of those who wrote fiction and were also interested in psychological persuasion.)

It’s this sensitivity to the world of narrative and imagination, Newitz suggests, that helped these writers to excel in the world of spycraft and psychological manipulation. Newitz themself is also a writer of three well-reviewed novels of speculative fiction, so their interest and sensitivity to this overlap makes a great deal of sense. In order to foster a world less riven by disinfo and psychological warfare, we need to better understand how these tools are embedded in narratives that get used to shape our world. “To achieve psychological disarmament,” Newitz writes in the introduction, “we’ll need to rethink the role of stories in our lives—and, more importantly, to change the way we act on the stories we hear.”

While it by no means shies away from the darker aspects of American culture and the hard realities we’re facing, Stories Are Weapons is more than just another slog through a dark and dreary world of conspiracy theories, paranoia, and creeping fascism. Throughout, Newitz stays resolutely focused on diagnosing problems for the purpose of laying out solutions, and looks for a way to write our way out of the mess we’re currently in.

The first third of Stories Are Weapons offers a prehistory of psychological warfare, beginning with the Indian Wars of the nineteenth century. America’s story about its westward expansion, as Newitz points out, was dependent on a paradox. On the one hand, there is what scholars refer to as “the myth of the vanishing Indian”—the repeatedly pushed line that we’d seen the Last of the Mohicans (and every other Native people) come and go, and the West was “a virgin land for whites to settle.” And yet, Newitz continues, it’s a “matter of public record that the U.S. War Department appropriated millions of dollars to fight the Indian Wars in the nineteenth century. If the enemy had already vanished … why the need for all that funding?” This contradiction was essential to ginning up public support for genocide, which had to be portrayed as a melancholic, foregone conclusion by a reluctant nation carrying out its destiny.

By establishing that America’s history with disinfo began with the Indian Wars, Newitz makes clear that these tactics, as scary and frustrating and anti-American as they may seem now, were crucial to the formation of the country as we understand it. Westward expansion could not have happened without this marriage of total war and psyops. And what becomes clear in Newitz’s timeline is how regularly narratives are built for the purpose of making violence seem inevitable. Stories limit interpretation, they exclude as outlying noise elements that may support counternarratives, and they create an emotional investment for a desired outcome.

From there, Stories Are Weapons turns to twentieth-century American military tactics of psychological warfare and—crucially—how those tactics differ from the kinds of weaponized storytelling that most of us now face every time we open a social media app. Among the more fascinating discussions in Newitz’s book is how very different the military’s use of psychological warfare is from the kinds of disinformation most of us are dealing with on a day-to-day basis. The American military’s use of PSYOPS turns out to have had a mixed success record, at best: For all the experimentation (via programs like the CIA’s MKULTRA) to create a Manchurian Candidate–style brainwashing program, the government has never been able to successfully condition people to act against their will. Rather, much of American propaganda has combined variations on the bog-standard “leaflets-and-loudspeakers” approach with hoping for the best. This strategy tended to work better during the Cold War, particularly in the wake of the Marshall Plan, when the United States was heavily invested—financially as well as ideologically—in winning hearts and minds.

But that only appears to work so long as the money spigot is turned on. As Russell Snyder’s Hearts and Mines: With the Marines in al Anbar; A Memoir of Psychological Warfare in Iraq makes clear, the only propaganda tool that has ever truly worked for the U.S. is bribery, primarily in the form of humanitarian and infrastructure aid. But sadly, Newitz goes on to explain, the military “never had enough money to pay for the damage that they had done to homes and infrastructure,” and so even the bribery failed to work in the long run, leaving the U.S. PSYOPS program “an old-school blunt instrument in a world where enemy tactics are agile and conditions are rapidly changing.”

Contrast these efforts with the work of Russia’s Internet Research Agency, or IRA, a private firm once owned by Wagner Group warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin, which was responsible for a massive disinfo campaign carried out via Facebook that targeted Americans during the 2016 election. Rather than persuading the enemy to change their ideology or belief, “Russian psyops are all about maskirovka, or baffling people with bullshit,” in the words of one American PSYOP trainer that Newitz spoke to (he even went so far as to give them a crash course on psychological warfare). In 2016, for example, the IRA set up two opposing Facebook groups: Heart of Texas and United Muslims of America. Using the social media site’s algorithms to build enrollment in each, the IRA then set the two against each other, announcing a Heart of Texas protest against a Houston Islamic center and a counterprotest by the United Muslims of America. The goal was not to advance a cause so much as to simply sow division and drive conflict between Americans. The IRA also waged numerous campaigns against those who supported Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, St. Louis, and elsewhere, arguing that neither Republicans nor Democrats could do anything to rein in police violence, hoping to depress turnout and build nihilism among the Democrats’ base.

Unlike American tactics, in Russia, government “agencies flood social media with misinformation,” which does not persuade so much as overwhelm and confuse people entirely. People stop believing anything is true and retreat to cynicism and conspiracy. This approach has the advantages of being both fundamentally more destabilizing and easier to pull off. As Ruth Emrys Gordon, another online disinfo researcher who is also a novelist, says, “It’s hard to get people to believe things, but it’s easy to get them unsure and confused.” The goal is to create what sociologist Jurgen Habermas called a “legitimation crisis”: a breakdown in meaning so fundamental that even basic communication, and the ability to agree on the most basic facts, becomes impossible.

“When the US military engages in PSYOPS,” Newitz explains, “a legitimation crisis is the last thing they want. They’re hoping to persuade people to take America’s side in a conflict, which means they want to shift the adversary’s political loyalties. If the target audience doesn’t believe any institution or government can be legitimate, then there’s no hope of that kind of persuasion.” Yet American political strategists have begun to find uses for this approach in elections—starting with Steve Bannon and Cambridge Analytica, these tactics were used “by Americans against Americans.” Total war had come home.

Among its many services, Cambridge Analytica specialized in identifying voters who might have latent authoritarian leanings. Its founder, Nigel Oakes, worked in advertising before starting Strategic Communications Laboratories, or SCL, which worked on foreign influence campaigns in places like Libya, Syria, and Iran; Cambridge Analytica, a subsidiary of SCL, was formed to focus on electoral politics at home in Great Britain and the United States. Scraping Facebook and exploiting its loopholes allowed researchers to gather demographic profiles on millions of users and develop a profile of people who “felt oppressed by political correctness,” in the words of whistleblower Christopher Wylie. These were people, Cambridge Analytica came to believe, who could be seduced by narrative and persuasion into backing an authoritarian candidate that they might not otherwise feel comfortable publicly supporting. And these were the people that Steve Bannon—the Trump adviser who leaned heavily on the firm’s data—sought to reach.

If the goal of military psyops was to “convince the enemy to change their behavior,” culture warriors like Bannon had two—entirely different—goals: “convince your audience that some of their fellow citizens are the enemy; and convince the enemy that there is something deeply wrong with their minds, and therefore they are not qualified to demand greater freedoms and personal dignity.” What started as an attempt to get people to buy things they don’t want, and became an attempt to win “hearts and minds” overseas has become this: an attempt to turn citizens against one another, convincing them that their neighbors do not deserve basic dignity.

To keep the book moving, Newitz drills down on a series of case studies rather than attempt an exhaustive history. Deeply researched and hewing to facts and history, Newitz is nonetheless, as their book’s title implies, interested in the meaning and value in storytelling instead of simply hammering facts and claiming “truth.” And while they remain clear-eyed on the problem and refuse to sugarcoat the task ahead, Newitz remains a dogged optimist, and their tone keeps the book from devolving into a merely depressing rehash of how terrible everything is these days. Particularly in the book’s third section, there is ample place throughout for wonder, for the celebration of Indigenous storytelling and the capacity for fiction and imagination to remake the world for good (as well as bad). It is also a book devoted to theorizing solutions, and ultimately Newitz is uninterested in a story that paints the problem as insurmountable or the cause as hopeless.

Because, just as stories wound, they can be repurposed and used to reshape this reality. Even though, Newitz notes, “Americans are not engaging in democratic debate with one another” and instead “are launching weaponized stories directly into each other’s brains,” nonetheless we still “have the power to decommission those weapons.” Newitz treats seriously the term “psychological warfare” as a weaponized tactic that produces its own form of trauma, arguing that we “need to take the harm from psychological war as seriously as damage from total war.” Using the language of therapy, Newitz concludes that “the only solution to political trauma is political transformation.” What does that look like?

Partly, it means awareness. “Achieving psychological peace,” they write, “doesn’t always require us to tell new kinds of stories. Instead, it involves understanding how many of our social interactions are shaped by the stories we’ve heard. It’s about recognizing weaponized stories when they come flying at us, instead of accepting them as factual or unquestionably good.” But awareness itself can come from competing, alternative stories, stories that push back against the monolithic conclusions of psychological war and offer alternatives to violence. In a chapter titled “History Is a Gift,” for example, they write of the importance of archives like the Southwest Oregon Research Project, or SWORP. Beginning in 1995, Jason Younker, Coquille tribal chief and anthropologist, and his colleagues began pulling out of national archives any and all material related to the Coquille nation and constructing an alternative archive, one that takes “the fantasy out of history,” in Newitz’s words, “often by collecting primary sources from the very organizations that tried to hide or ignore Indigenous claims to the land.” This reconfiguration of a colonial archive offers a whole new means of creating narratives and telling stories; more than a defense against psyops, they “are a commitment to a new story about identities made whole in an ongoing psychological peace process.”

In the meantime, Newitz proposes ideas that may seem more familiar, such as social media “first responders,” online moderators “who can spot propaganda outbreaks and put them out before they explode, and “firebreaks” such as “technical features that can slow the spread of weaponized information.” Hopefully, Newitz believes, this kind of work “will make it easier for the public to recognize and interrupt influence operation kill chains next time.”

There is a problem here, of course, in that these two solutions (unlike the SWORP archive) require the buy-in of both government and tech companies, which is to say, they’re nigh impossible in the current environment. But a larger difficulty is right there in that word “public.” At one point, it may have made sense to talk about the “American public” as a homogenous, unified group, but that is no longer the case. In fact, one could say that one of the hallmarks of American history—as Newitz also discusses—is that the “American public” is usually constituted so as to exclude at least some portion of the population. As those segments of Americans—Indigenous Americans, immigrants, Black Americans, the LGBQT community—have fought to be included in the idea of the American public, resulting in increasing pushback from illiberal segments of American society, the fiction of a single “American public” has shattered. We now have a series of competing definitions of what that “public” is, and what it means to be a “true” American.

Those of us who want a less fractured United States, who want our friends and neighbors to not live in fear of violent acts, either by the police or by extrajudicial forces, those of us who fundamentally believe in the American project of giving everyone an equal opportunity to prosper and thrive in this world—we need a new and better definition of who that public is, one that’s less vulnerable to tribalism. We need a story that accounts fundamentally for the people in our community who simply do not want this, who thrive on disinfo, chaos, and division. It’s going to take more than rainbow-lettered “In This House We Believe” yard signs, and there aren’t any quick fixes available.

This is why the SWORP example seems particularly evocative—not only does it not require legislation or reining in social media behemoths, it also points to the long commitments needed to build new generations of stories; as much as we need to triage our current calamities, we also need to lay the groundwork for future generations. As with trees, so too with stories: The best time to tell a story about the future is 50 years ago; the second-best time is today.