The Woman Who Defined the Great Depression

Sanora Babb spent her life dealing with all the multifarious daily perils that prevent writers from writing. She was raised in poverty by a mother who was only 16 when she gave birth to her and an abusive father who spent his days playing semi-pro baseball and gambling. From the age she could walk, she was running errands for her parents’ bakery and, later, helping them raise crops until drought put their mortgaged farm out of business. She rarely had time for school (or even enjoyed easy access to one) and learned to read from pages of The Denver Post that were pasted to the crude walls of their dugout home in East Colorado. (Her father described the place as looking “like a grave.”)Babb’s observations of rural poverty, particularly during the Depression and the Dust Bowl, would filter through the imaginations of millions of Americans in years to come—though indirectly and often without credit. Babb knew intimately of what she wrote. Even when her parents started making better money, and she worked hard enough to earn a rare scholarship to the University of Kansas, her first teaching job depressed her so deeply that she couldn’t keep it for long. She was often required to do janitorial work as well as run classes, and couldn’t bear to see children come to school as poorly clothed and fed as she had been at their age. By the time she moved to Los Angeles and found work as a radio and print journalist and screenwriter in the late 1920s, the Depression hit and she spent several months sleeping rough in Lafayette Park with other out-of-work writers.The first few decades of her life were an endless round of desperate exigencies. When she finally started making a decent living, her passion for political causes took up even more of her time. She joined the John Reed Club, traveled throughout Europe and postrevolutionary Russia, and attended one of the first League of American Writers Congresses in New York City in the mid-1930s, driving there cross-country with Tillie Olsen and driving back again with Nelson Algren. In her twenties, she became the primary carer for her younger sister, who suffered from mental illness; and in later years, from 1971 to ’76, she cared for her husband, the great cinematographer James Wong Howe, after he suffered a major stroke. Whatever the decade, and whatever the year, it was rare for Babb to scrape up more than a few hours here and there to focus on the great stories, novels, and poems she had in her.And yet she managed to wrestle several hard-won achievements into the world: She wrote probably the greatest novel ever written about the Dust Bowl, Whose Names Are Unknown, only published many decades after she sold the first chapters and outline in 1938; she excelled in several different literary forms—from journalism (she co-edited a radical newspaper with Claud Cockburn in London in the 1930s) and field notes from California migrant camps to memoir, lyric poetry, short stories, and even screenwriting; and despite her tendency to be more openly supportive of other writers than they ever seemed to be of her, her life was so rich with good work that almost all of it eventually achieved publication. The most profound obstacle Babb faced in her strenuous life was a case of bad writerly luck of now-legendary proportions. Although she took the cautious upward route of many self-taught young writers, she never caught the decisive break she needed.The most profound obstacle Babb faced in her strenuous life was a case of bad writerly luck of now-legendary proportions.Just when her carefully composed early short stories and essays began attracting the attention of New York editors, she signed a contract for a novel about the Dust Bowl, based on her youthful experience in Red Rock, Oklahoma; and in order to further research the westward migration of her fellow Oklahomans, she took a volunteer job with the Farm Security Administration in Southern California, helping to move refugees into state-funded, self-governing resettlement camps. Initially, Babb only intended to gather information; but as in everything she did, she soon developed a passionate concern for the people she met and the stories she heard, hurling herself into the project with the fierce intensity of a woman who always seemed to be working twice as hard as everyone around her.Her supervisor, Tom Collins, summed up her achievement in a letter he wrote to Babb at the conclusion of her work:1. You visited tents, shacks, cabins and hovels. 472 families or 2175 men, women, and children.2. You interviewed and signed up 309 families or 1465 men, women and children.3. Total families you met and know 781.4. Total individuals you met and know 3640.5. You, therefore, spread happiness and hope to all these—and we thank you with all our hearts.Her work for the FSA yielded hundreds of pages of notes and photographs, many of which were posthumously gathered in On the Dirty Plate Trail: Remembering the Dust Bowl Refugee Camps (2007). These lab

Sanora Babb spent her life dealing with all the multifarious daily perils that prevent writers from writing. She was raised in poverty by a mother who was only 16 when she gave birth to her and an abusive father who spent his days playing semi-pro baseball and gambling. From the age she could walk, she was running errands for her parents’ bakery and, later, helping them raise crops until drought put their mortgaged farm out of business. She rarely had time for school (or even enjoyed easy access to one) and learned to read from pages of The Denver Post that were pasted to the crude walls of their dugout home in East Colorado. (Her father described the place as looking “like a grave.”)

Babb’s observations of rural poverty, particularly during

the Depression and the Dust Bowl, would filter through the imaginations of

millions of Americans in years to come—though indirectly and often without

credit. Babb knew intimately of what she wrote. Even when her parents started

making better money, and she worked hard enough to earn a rare scholarship to

the University of Kansas, her first teaching job depressed her so deeply that

she couldn’t keep it for long. She was often required to do

janitorial work as well as run classes, and couldn’t bear to see children come

to school as poorly clothed and fed as she had been at their age. By the time

she moved to Los Angeles and found work as a radio and print journalist and

screenwriter in the late 1920s, the Depression hit and she spent several

months sleeping rough in Lafayette Park with other out-of-work writers.

The first few decades of her life were an endless round of desperate exigencies. When she finally started making a decent living, her passion for political causes took up even more of her time. She joined the John Reed Club, traveled throughout Europe and postrevolutionary Russia, and attended one of the first League of American Writers Congresses in New York City in the mid-1930s, driving there cross-country with Tillie Olsen and driving back again with Nelson Algren. In her twenties, she became the primary carer for her younger sister, who suffered from mental illness; and in later years, from 1971 to ’76, she cared for her husband, the great cinematographer James Wong Howe, after he suffered a major stroke. Whatever the decade, and whatever the year, it was rare for Babb to scrape up more than a few hours here and there to focus on the great stories, novels, and poems she had in her.

And yet she managed to wrestle several hard-won achievements into the world: She wrote probably the greatest novel ever written about the Dust Bowl, Whose Names Are Unknown, only published many decades after she sold the first chapters and outline in 1938; she excelled in several different literary forms—from journalism (she co-edited a radical newspaper with Claud Cockburn in London in the 1930s) and field notes from California migrant camps to memoir, lyric poetry, short stories, and even screenwriting; and despite her tendency to be more openly supportive of other writers than they ever seemed to be of her, her life was so rich with good work that almost all of it eventually achieved publication.

The most profound obstacle Babb faced in her strenuous life was a case of bad writerly luck of now-legendary proportions. Although she took the cautious upward route of many self-taught young writers, she never caught the decisive break she needed.

Just when her carefully composed early short stories and essays began attracting the attention of New York editors, she signed a contract for a novel about the Dust Bowl, based on her youthful experience in Red Rock, Oklahoma; and in order to further research the westward migration of her fellow Oklahomans, she took a volunteer job with the Farm Security Administration in Southern California, helping to move refugees into state-funded, self-governing resettlement camps. Initially, Babb only intended to gather information; but as in everything she did, she soon developed a passionate concern for the people she met and the stories she heard, hurling herself into the project with the fierce intensity of a woman who always seemed to be working twice as hard as everyone around her.

Her supervisor, Tom Collins, summed up her achievement in a letter he wrote to Babb at the conclusion of her work:

1. You visited tents, shacks, cabins and hovels. 472 families or 2175 men, women, and children.

2. You interviewed and signed up 309 families or 1465 men, women and children.

3. Total families you met and know 781.

4. Total individuals you met and know 3640.

5. You, therefore, spread happiness and hope to all these—and we thank you with all our hearts.

Her work for the FSA yielded hundreds of pages of notes and photographs, many of which were posthumously gathered in On the Dirty Plate Trail: Remembering the Dust Bowl Refugee Camps (2007). These laboriously accumulated pages would testify to two overriding aspects of Babb’s character: that she wasn’t afraid of work and that she possessed an almost bottomless compassion for everybody she met who led a tougher life than she had.

When a friend of her supervisor arrived at the camps to research his own novel, Collins convinced Babb to turn over a copy of her extensive field notes. The writer’s name was John Steinbeck; he had plenty of talent and compassion of his own; and he knew how to make quick use of good material when he saw it. Much of Babb’s work went straight into Steinbeck’s next draft—especially the portions set in a California refugee camp. And after The Grapes of Wrath became a bestseller, Babb turned in the final draft of her own Dust Bowl novel to Bennet Cerf, only to be told that the bookstores weren’t big enough for two novels on the subject. And so Babb’s novel, titled Whose Names Are Unknown, lay unpublished—despite continuous revisions and submissions to alternate publishers—for nearly half a century.

Which is not to say that Steinbeck didn’t acknowledge how much he was aided by Babb’s field notes. In fact, he dedicated Grapes to the individual who he felt had most helped him secure those valuable pages: Sanora Babb’s supervisor, Tom Collins.

Even if Names had been allowed to compete with Grapes of Wrath in the literary marketplace, it would almost certainly have failed to outsell or outshine it. Babb’s work was largely antithetical to that of Steinbeck, and its “message” was a lot more complicated. While Steinbeck focused on the road trip carrying the Joads away from their already collapsed farmland, the entire first half of Babb’s novel describes several years of the travails of the Dunne family, who struggle to grow broomcorn and wheat while their land grows increasingly parched, dust-storm-ridden and uninhabitable. In the second half of Babb’s novel, the Dunnes don’t simply submit to the California farm growers, or lose their temper, like Tom Joad, and flee, but bear down and become increasingly involved with labor organizers and strike actions.

Steinbeck’s prose infused the landscape with almost heavenly ambience, seeming to argue that the world was bountiful enough for everybody, if wealthy landowners could be forced to stop hoarding its riches. Babb’s prose, however, doesn’t exude the same effulgence; and while Steinbeck’s characters never really surpass their essential nature (whether they’re the drunken, well-meaning paisanos of Tortilla Flat or the always-striving Joad family who can never outstrive an exhausting world), Babb expects more from her principal characters than to die, lose hope, relapse into natural weaknesses, or wither away. Her characters are never beaten down so hard they don’t find a way to climb up out of their failures and give life another chance.

The conclusions of Grapes of Wrath and Names couldn’t make this distinction more clear. Steinbeck’s Joads are ultimately beaten down to little more than their barely pulsing biologies—huddling together for warmth while the bereaved mother, Rose of Sharon, breastfeeds a starving man. Babb’s characters struggle to their last narrative breath to envision a future that will have them. In the concluding paragraph of Names, confronted by corporate forces that own “guns and clubs and tear gas and vomit gas and them vigilantes paid to fire the guns,” Babb’s Julia Dunne sees one thing “as clear and perfect as a drop of rain. They would rise and fall and, in their falling, rise again.”

It’s hard to recall a writer who writes more vividly and affectionately about American landscape than Babb; her characters journey across its vastness with an almost invulnerable affection for what surrounds them, whatever cataclysms erupt. Early in the novel, when Julia and her daughters are pushed out of a neighbor’s home into an oncoming dust storm, the true violence isn’t that of nature but of the neighbors, who have ejected them from their home so they can take care of themselves. And nature is always beautiful, even when it’s at its most threatening:

They were almost a mile way, walking in the hollow, when the rain began in large slow drops, and the far horizon quivered with sheet lightning. Fork lightning snapped suddenly, splitting the moving clouds, flashing close to the wires. The whole flat world under an angry churning sky was miraculously lighted for a moment. A strange liquid clarity extended to the ends of the earth. Julia saw the trees along the creek and animals grazing far away. The bleak farmyards with their stern buildings, scattered sparsely on the plains, stood out in naked lonely desolation. A sly delicate wind was rising. Their dresses moved ever so little. Thunder clapped and boomed. They were afraid of the electricity that speared into the ground with a terrifying crash after. Julia stopped for a moment to get her breath and look at the approaching storm. Then she took Lonnie from the bumping cart and pulled her along by the hand, while Myra pulled the cart and clung to the pail of milk. They moved off the road away from the wires, going through the open hollow.

There is no Steinbeckian pantheistic force in Babb’s landscapes that joins human beings into a continuous environmental oneness; there is only nature’s vast beautiful indifference across which people live, love, struggle, and yearn. When her daughter asks if a cyclone might be forming, Julia consoles her: “It’s only an electric storm.… Rain won’t hurt us. It’s just scary.” Nature is neither malign nor consolatory; it’s implicitly nothing more or less than itself. And fear doesn’t arise from the world; it arises from individuals when they are bereft of one another.

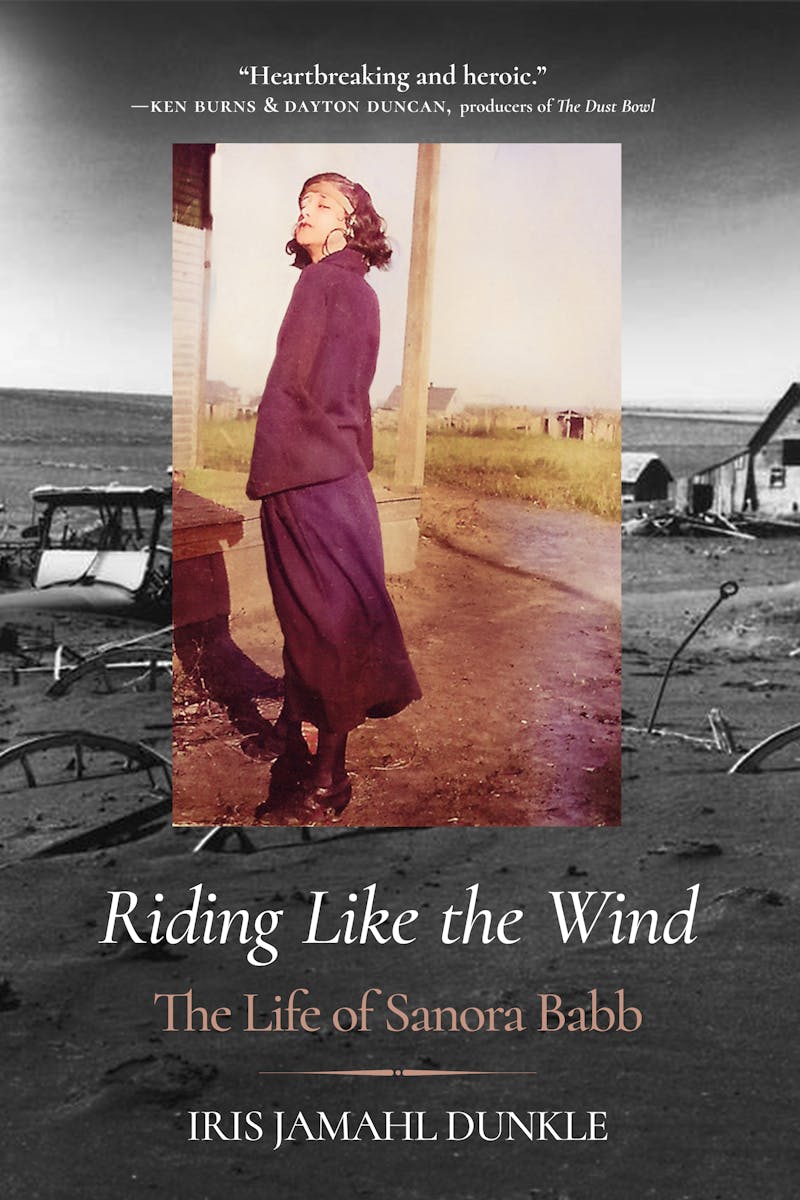

The failure of Names wasn’t the only event in Babb’s long event-filled life that was difficult to distinguish from legend. Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s compassionate and respectful biography, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb (largely based on stories recounted by Babb and her family, as well as passages from Babb’s work), is filled with tales of a life that was lived to almost tall-tale proportions. At the age of 5, Babb earned the nickname “Cheyenne—Riding like the Wind” from an Otoe chief after the pony he gave her went galloping wildly out of town while unyielding young Babb held on tightly, bareback. And though she was unable to start school full time until age 10, she worked hard enough to be named class valedictorian—only to have her graduation speech cut at the last minute when the school authorities decided not to honor the daughter of a notorious local gambler.

As a young woman in Los Angeles, she went out to MGM looking for screenwriting work, where she caught the always-roving eye of Irving Thalberg, who invited her back to his office to sign up for a different career entirely—one that probably required spending at least some time on the casting couch. She turned down both offers and, when later asked if she was an actress, replied, “No. I’ve just had a narrow escape.” At one point, when she was out on a date with her eventual husband, James Wong Howe, a “finely dressed” woman drove up behind them in her car and, angered by the sight of a white woman with an Asian man, shouted abuse. In reply, Babb engaged in a street altercation that, by the end, left the woman shouting “My hat! My $100 hat!”

This absorbing biography, written with both affection and admiration, shows Babb as one of the most indefatigable characters in American literary history. Like Edna St. Vincent Millay, the poet who most inspired her, Babb “wasn’t someone who believed in monogamy,” and she happily shared her passions with many notable men—such as William Saroyan and Ralph Ellison. (In fact, her second novel, The Lost Traveler, is one of the few naturalistic novels in which the sexually adventurous young woman isn’t punished for moral failure, as Theodore Dreiser’s antiheroine is in Sister Carrie or Kate Chopin’s Edna Pontellier is in The Awakening.) She traveled extensively, often hitchhiking alone across country and through Mexico; she wrote the lyrics for a popular song, which were then “swiped” by someone who published them under their own name; and she organized a walnut growers’ strike in Modesto, California, which caused her to spend at least one night in jail.

It was only when Babb began suffering bouts of ill health—partly the result of an impoverished childhood diet and partly from a nervous breakdown set off by learning that her former lover Ralph Ellison had remarried—that she finally settled down exclusively with Howe. But even then, she always seemed to be doing the work of three or four women. She helped him buy and manage a Chinatown restaurant and took charge of long visits from his family while he was working on movie sets. They surreptitiously bought a house together in the Hollywood Hills, and after California’s ban on interracial marriage was found unconstitutional, they married in 1949. But even then, it wasn’t easy to find a judge who would perform the service.

She was clearly as passionate in her political activism as she was in her personal relationships. After many challenging years of marriage, when her relationship with Howe had not been entirely monogamous, she eventually settled down, and the two would often write “small sweet love notes” and leave them around the house for each other to find. One of her best short stories, “Reconciliation”—about a married couple coming together again after a separation to tend their neglected garden—reads like an homage to their long, often difficult, and just as often devoted, relationship.

While Babb endured more than her share of bad luck in publishing, she developed many devoted friends and fans who saw her through decades of darkness into a late middle-aged period that approached modest fame. Her short stories were regularly published in various significant journals and reprinted in “best of the year” volumes; she found an agent, and eventually sold and published her second novel, The Lost Traveler, based on childhood memories of growing up with a sometimes brutal, errant father. Her 1970 memoir, An Owl on Every Post, earned a brief time on bestseller lists, adorned with quotes from her longtime friends and admirers Ralph Ellison and Ray Bradbury.

Dunkle’s biography likewise relies on the work of Babb’s friends, scholars, and especially her late-life agent, Joanna Dearcrop, who helped Babb finally get Whose Names Are Unknown published after a half-century delay in 2004, while Babb was lying in bed with an exhausted body that couldn’t carry her much further. And eventually, her remarkable field notes, cited by Ken Burns in his Dust Bowl documentary on PBS, led to new editions of her poetry and prose.

The major question about Babb’s remarkable work is not “Why did she write so little?” but rather: “How did she find the time to write anything at all?”

While she is best known for a novel that wasn’t published until she was almost dead, her gifts are beautifully displayed in numerous short stories and poems that carry readers through regions of memory, landscape, and experience. On one journey through Mexico and South America, Babb gathered material for “The Larger Cage,” about an orphan who finds a home (of sorts) with a family that sells wild local birds to tourists; they teach him to “train” the birds by filling their bellies with buckshot, which inevitably kills them. But human cruelty is never the subject of Babb’s fiction—rather it’s the human ability to bring kindness into the world, and the protagonist of “The Larger Cage” learns that there are better ways to train beautiful birds than by tormenting them.

It is perhaps the most remarkable (and unsatisfactory) fact of Babb’s life that while she failed to produce big novels at times that were acceptable to the publishing industry, she spent her life succeeding in far less commercial forms—such as the short story, the lyric, and the memoir. Many writers are recalled for the great things they achieved in life apart from their living of it; but Babb’s greatest genius may have been her ability to produce lasting work without leaving anyone in her life behind.