Ukraine’s plan B: turning everyday citizens into defenders

As Russia's aggression continues, Ukraine transforms its civilians into a force capable of "total resistance."

Kaboom!

The explosion comes out of thin air. I drop to the forest floor and press into the wet spring soil that reeks of earthworms, hands on my neck, heels together.

Liubomyr, a burly man in fatigues, smirks: we triggered his tripwire, setting off a sound grenade. “You’re all 300s,” he declares, using the Ukrainian army code name for wounded in action. We’re all injured while attempting to rescue our wounded comrades from a mortar attack.

“Scotch, Scotch, we have two 300s, I am heavy. Send reinforcements!” our leader, Collibri, screams into a walkie-talkie. She is a lively brunette whose leg has just been blown off.

In this exercise, Collibri died. She did not twist her tourniquet strongly enough to dam the river of blood gushing out of her limb. Our trench had been ambushed, and the enemy shot our evacuation team as they attempted to drag the wounded out of the spring jungle near Kyiv.

We, a ragtag group of civilians, were “killed” endless times during our five-day army boot camp, where seasoned combat veterans and emergency medics taught us how not only to survive but also assault enemy positions.

For five days we traded our lives as computer engineers, software developers, teachers, journalists, students, translators, and barbers for callsigns. Civilian life was put on hold while we learned to destroy those who want to destroy us.

My callsign is Leia. My usual job is writing and editing the constant stream of news from the frontline for Euromaidan Press. I am here because I am ashamed of Ukrainian men fleeing the country to evade mobilization while my friends on the frontline, exhausted from two years of war, say that the only way out for them is to be maimed or killed, as no reinforcements are coming to replace them. There are so many more Russians than us; Women likely will need to serve.

Will I be more useful on the frontline instead of creating my endless clatter at the computer as the editor of this outlet?

Do I have a right to do this, with my small kids? Do I have what it takes to kill an invader? I am here to figure this all out. I have five days.

Bombs, guns, and drones

Since its founding in the summer of 2023, the Kyiv-based Center for Preparation for National Resistance has trained 18,000 people. Civilians like us are only a small part: most were either active servicemen or university students undergoing mandatory military training. The goal: total resistance.

“Civilians need to know what weapons are, how they should be handled, how they are used in battle, how one should move in battle, how to use grenades. They need to know tactical medicine: it will come in handy not only in military affairs during war, but in ordinary civilian matters. Anything can happen, and they’ll know what will help,” said Blaizer, a serviceman who fought in the elite 5th Assault Brigade and who is now a military instructor.

No one knows when the war will end, said Blaizer. Civilians need to be prepared if the Russians are again at the gates of Kyiv, as they were in 2022.

Russian troops planned on taking the Ukrainian capital within three days after launching the full-scale war on 24 February 2022. Their plan failed, thanks to the unexpected resistance of tens ordinary civilians who took up arms. Then, weapons were handed out to everybody, regardless if they had any training.

Tens of thousands of Kyiv residents joined the territorial defense forces, providing additional manpower and support to the regular army, setting up barricades, and engaging in urban warfare tactics, ultimately helping to save Kyiv from falling under Russian control

Granted, there was a lot of friendly fire, and the military played a huge role. Still, Kyiv was defended, “thanks to the spirit of the people,” Blaizer said. “It showed that we can do it if the need comes.”

In the five days at the base, our time is divided 30/70 percent between lectures and practice. We learn how to handle and shoot two rifles most commonly used in the Ukrainian Army – the Kalashnikov and AR – using airsoft bullets. We are trained in basic military tactics: to move with rifles in pairs (one covers, the other one runs forward or retreats), hurl grenades, and take cover when a grenade is hurled at us (face into the ground, hands protect the neck, heels into the ground).

We are instructed to keep our elbows close when shooting and our knees together – to protect the arteries that, if ruptured by a bullet or shrapnel, could lead to massive blood loss and death. We learn to carry our wounded comrades out from enemy fire and administer first aid using the MARCH algorithm. We make a MAVIC wedding drone, indispensable for surveillance in the war, which is increasingly labeled as a “war of drones.” We learn to fly these drones in figure eights. We attempt to traverse a path full of mines and tripwires – without triggering them.

Finally, we scream at the top of our lungs to get the adrenaline pumping as we charge at an enemy trench and storm a building supposedly held by Russians with airsoft rifles and smoke grenades.

Shoot, dig, and hide

Boom. A grenade falls to our feet from above as we attempt to toss in grenades through the broken windows and charge through the knocked-out doors.

“You’re all dead!” shouts Old Man, a 1.90-meter-tall veteran of three wars: the one in Afghanistan, the first Russian invasion of 2014, and the full-blown Russian war of 2022.

Had we dropped to the asphalt, our feet toward the explosion, we could have survived.

We don’t have the battlefield reactions yet: it is hard enough coordinating the assault of the dilapidated summer camp building.

In our attempt on the building, one in the pair holds the sector in front of the building, and the other holds the rear and throws the grenade. We fumble. We struggle to release the pins on the grenades, and when we finally throw them, they bounce from the window frames back at us, while our enemy, civilians who have undergone more rigorous training, shoot with plastic pellets from above.

Boom. Rat-a-tat. So many ways to be killed.

“Five days will give you only a minimal base,” says Blaizer. “You’ll know how to handle weapons safely, so you won’t just wave them and shoot randomly.”

Without further training, civilians can only participate in simple defense-related tasks involving weapons, such as manning checkpoints, checking vehicles, and patrolling.

Blaizer believes that Ukraine should legislate mandatory long-term military training, after which civilians will go into the reserve forces. Women should serve, too, like in Israel: “With such a neighbor as Russia – look at how many millions they have – everyone needs to be prepared.”

For our newly learned skills to be useful, they must be practiced regularly until they become a reflex, for instance, keeping your finger off the trigger when carrying the rifle, lunging to the side after you fired a round to evade the response fire, keeping low to lessen the chance of a bullet hitting you.

These reflexes will save you at war: there is no time to think amid explosions. Plus, sleep deprivation dulls your mind. This is why aspiring soldiers must train, ad nauseum, to get to the point of automatism.

Shoot, dig, and hide: these are the three things a soldier must know. But old doctrines do not work anymore. Drones have changed the battlefield, says Old Man. NATO doctrines do not work either. They require a numerical advantage over the enemy, which is unrealistic with Ukraine’s lack of airpower, manpower, and ammunition. Therefore, Ukraine is forced to search for new approaches. It has become a training ground, and everybody is learning in this war: Ukraine, Russia, and NATO.

The number one thing that soldiers must improve is their endurance, says Old Man, as we pant, racing from obstacle to obstacle. Six months can go into training a good infantry soldier, and most of that is simply toughening up. Not only the young can do this: infantry soldiers can be up to 60 years old, he says.

Sometimes, civilians taking the five-day course discover they want to continue training. For them, the training center created a group called Alpha-Bravo, which provides more regular instruction. Some realize that the army is not as scary as they thought and decide to enlist.

However, systematic problems stymie Ukraine’s much-overdue mobilization efforts.

A lack of ammunition means “meat grinder assaults” occur not only in Russian forces: troops are forced to defend their positions without artillery support, leading to many deaths. And lacklustre commanders, who don’t care about the lives of their subordinates, are all too common.

Service in the army is now a one-way ticket: there is no procedure for demobilization. Despite Ukraine hiking the payroll of soldiers at the frontline, it is still not enough to motivate people to risk their lives, Blaizer says.

Plus, if a soldier is injured, he’s basically on his own to figure out a way to get treatment and earn a livelihood. If he is killed, his family will need to go through bureaucratic hell to get the promised compensation. Many simply give up without getting it, Blaizer explains.

A game that trains how to die

Russia’s war has shown the European Union that the post-Second World War peace dividend era is over, says UK Defense Minister Grant Shapps. The EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell shares this view: Europe “believed that peace was a natural state of things, and that is sadly not true.”

The continent must re-learn how to fight. But how does one do that?

Old Man offers some battle-hardened wisdom.

He says in their first battle, only 20% of soldiers hit their enemy; others shoot into the air, or simply do not shoot. They were afraid to cross the line, to kill a man, says Old Man.

His secret: don’t think that the invading soldier has a family. Don’t pity yourself.

In front of you is simply the enemy.

If you hesitate, he will shoot you, and then come rape your wife and your children. Do not tell yourself, “If I resist, they will massacre me.” They will do that anyway, but at least your death will not be in vain.

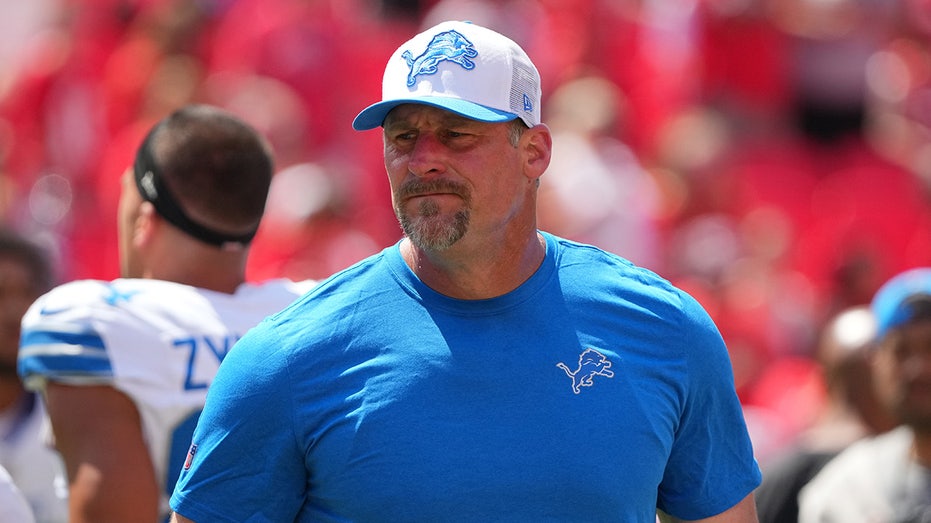

Civilians practice assaulting an enemy building during an army boot camp near Kyiv. Photo: Alya Shandra

“A German killed near Lviv will never appear near Moscow,” the Soviet Army was told in the Second World War, Old Man says, “Kill the fascist, here and now.”

For Psychologist, a friendly white-haired instructor who helps our little civilian brigade maintain morale and, therefore, fighting spirit, the answer is simply training – and adrenaline.

“Are you ready?” he screams at the top of his lungs.

“Ready,” Loki, a quiet mid-aged woman who works as a translator, murmurs.

“Are you ready?! I need you to scream!”

Psychologist coaxes her again and again to shout: it is a signal of sufficient adrenaline. Without it, we won’t have the strength to attack the enemy trench: you must first hurl the grenade from afar, drop to the ground and suppress the enemy with gunfire, charge, and hurl another grenade, he says:

“This is why commanders will scream in an absolutely insane ‘adrenaline’ voice during battle and during training.”

Everyone can be a warrior, says Psychologist. The question is whether you grow up in an environment that prepares you for that possibility.

“Kids playing war is normal. It’s normal to have military training in schools. In the 60s, we were twiddling around with wooden rifles. We designed tanks and dragged them around with us, because the aftermath of war was everywhere around us. I was a Red Army soldier at a play in kindergarten. We played war during all my years in school, and got military training in the last five. We were mentally prepared to become future warriors. And so, when Russia invaded, I simply stood up at my age of 66 and went to the military enlistment office.”

War is a state of extremity, when the usual peaceful way of human life gets suspended: you need to protect yourself and your family. For a warrior to function in this state, the army system ensures that special exercises and measures are taken to improve his or her morale: boosting it is the number one task for any commander.

Psychologist explains what happens to a man once he enters the army.

“When we live in the civilian world, we have red lines: do not kill. During war, those red lines are discarded: you need to defend. Also, a man enters another universe, one of powerful male relationships, male support, friendship. And he feels like a man to the fullest and feels satisfied when he does a man’s job, goes through trials and challenges, and overcomes these challenges. Only fools are not afraid of death, but he goes forward, overcomes obstacles, and gets a kick out of it, but only when he is mentally prepared! Tamed fear becomes a friend.”

Women serving in the forces alter this male universe. It becomes more humane. Mixed male-female combat units are the best, Psychologist says. The men become less rude and more father-like and start caring more about their own guys.

How can one overcome the fear of death and disability? Psychologist says you simply get used to it. Death lurks all around us. We could die or be crippled each day on the road, or simply on the street, but we avoid thinking about it.

“When you start working with the fact that you are mortal, you start preparing for different scenarios. And when you start preparing, you are not afraid anymore,” Psychologist says.

The callsigns we traded for our names in this center are part of the rite of readiness for death. A callsign is less personal than a name and steers soldiers towards working, rather than friendly, relations. It offers psychological protection against the inevitable tragedy of comrades being killed, Psychologist explains.

Bones, guts, and blood

Dying on the street has become a more likely scenario in the last two years in Ukraine.

This is why Scotch, a 29-year old software developer and our brigade commander, always takes a 1.5-kilogram combat medical kit when going outside. “Say, we go to the park, and a ballistic missile flies in, and my leg is torn off. Or my husband’s. What are we going to do?”

Her answer: always carry a tourniquet. This simple device will allow clamping down a torn limb, or a limb with a ruptured artery, when a person can die from extreme blood loss in a matter of minutes. Soldiers carry several of these whenever they go out for a mission and are ready to apply them to themselves if the need comes.

Civilians learn to apply the MARCH medical aid algorithm at an army boot camp for civilians. Photo: Alya Shandra

I twist, twist, and twist the blue training tourniquet. My leg turns blue and cold, the pain is excruciating. But I still did not twist enough. “You just bled to death,” declares Mavka, our medical instructor.

Once the blood flow to my leg is cut off, there are two hours before necrosis will start, and, possibly, amputation will be needed. To avoid this scenario, the injured soldier must get to medical professionals within two hours; however, average evacuation times are four to six hours.

Combat medics can be trained in tourniquet conversion, which can save more limbs. But we are simply rookies. Now, stopping the massive bleeding, the first letter in the MARCH combat medic life-saving algorithm is the ultimate priority.

We twist the tourniquets. We jam clotting gauze into rubber wound moulages fastened to our brigade members’ loins, where a tourniquet cannot be applied. Jam, jam, jam until your fingers ache. Otherwise, she’s dead.

Scotch studied physics, but her childhood dream of becoming a doctor is still alive: she learns tactical first aid, to prepare herself for “all scenarios.” This is why she attended many medical training sessions, which are now ubiquitous in Kyiv. Also, she watches many gory videos of first aid administered during emergencies: the plan is to desensitize her aversion to torn wounds and blood.

“You get used to everything,” Scotch says. “It’s not like you were born with a fear of blood and that’s it, you can’t be a medic.”

Becoming a medic is a popular choice for women who join the army, says Vita, a 20-year-old marketing specialist. Other roles such as infantry are physically strenuous. Because of this, her boyfriend’s brigade, now at the front, has no women. Piloting a drone is another popular choice for women. Perhaps Vita will need to serve: there are not enough soldiers, and the remaining men are trying to hide. She is ashamed that they try to flee over the border.

“Nobody wants to die. My boyfriend doesn’t want to die. Somebody’s dad doesn’t want to die. But a child that doesn’t want to fight in our army is subconciously preparing to fight in a foreign army,” Vita says of the looming possibility that, if Russia wins in Ukraine, men will be drafted to fight Russia’s wars.

Some people try to hide their heads in the sand, says Steier, a computer engineer who survived Russian occupation in Kherson. But he wants to better prepare himself for anything that comes. So does Vikusia, a teacher for visually impaired children and a mother of two. If not for her 10-year old younger daughter, Vikusia would likely enlist.

“We have to protect this country. We are a strong, beautiful nation.We have to develop. But an avalanche of hopeless gloom and darkness is really coming towards us. This is bad, very bad,” she says of her decision to learn the ABCs of military matters. “Because of my profession, I know for whom and why we are fighting.”

Related:

- Ukrainian soldiers hold back Russian onslaught with scavenged 1950s howitzer, DIY shells

- In a Ukrainian soldier’s mess tin: balancing abundance and malnutrition on the Ukrainian frontlines