Ukrane’s top economist: Polish border blockade a “litmus test” for EU integration

Hennadiy Chyzhykov, president of Ukraine's Chamber of Commerce, says resolving the trade dispute with Poland over agricultural exports is crucial for Ukraine's EU accession process, revealing deeper issues around competition and solidarity.

Protests of Polish farmers against Ukrainian food imports have been ongoing since November 2023. Cargo traffic fell to a standstill as Polish opponents of trade liberalization with Ukraine blocked the border for lorries, increasing Ukrainian drivers’ waiting times to several weeks. Ukraine’s war-ravaged economy had taken a blow, but despite staunch support for Ukraine, the Polish protesters were adamant to keep blocking traffic, to the tacit support of Polish authorities.

The protests significantly decreased, and the last border checkpoints were unblocked on 29 April, after the EU limited imports of certain agricultural products from Ukraine.

To understand how the Polish border blockade affects upcoming negotiations regarding Ukraine’s EU integration, we talk to Hennadiy Chyzhykov, president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Ukraine, to understand how the Ukrainian war-time economy reacted to the Polish border blockade, how it will affect Ukraine’s EU integration, and how fast the integration process can be.

Piotr Soroczyński, the chief economist and director of the Economic Policy Office at the Polish National Chamber of Commerce, outlined the Polish perspective in our previous interview:

EP: How would you characterize the current situation with negotiations between Ukraine and Poland to solve this border and trade issue? How close have we come to a solution?

Hennadiy Chyzhykov: The question regarding our relations with Poland is both relatively simple and complex at the same time. Current negotiations have more of a political than an economic character.

In almost 20 years of EU membership, Poland has gained extensive experience using European Union instruments. This includes the use of grants, various projects, and programs to protect and develop its domestic market. And it so happens that the agricultural sector has become a subject of dispute.

We understand that the potential of the Ukrainian agricultural sector is huge, 3-4 times larger than that of Poland. I’m not talking about the economy as a whole but about the agricultural sector’s potential.

At the same time, for us, for the Ukrainian agricultural sector, Poland has never been a key market. Italy, Spain, Egypt, China, and countries in Asia and Africa were. However, many politicians on the Polish side have started using the subject of Ukrainian exports.

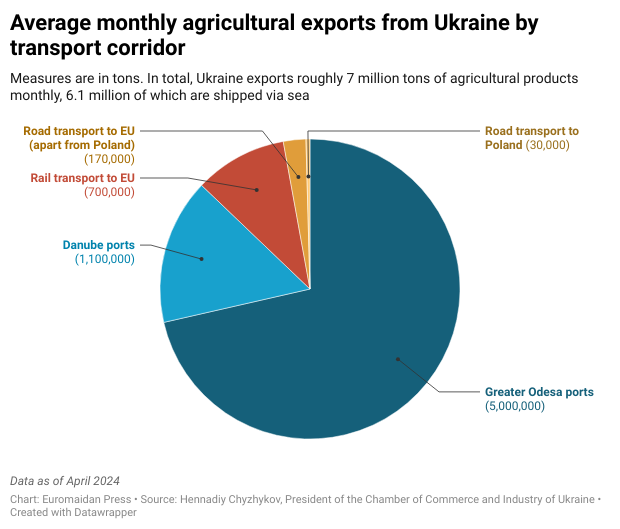

On average, Ukraine exports about 7 million tons of agricultural products monthly. The most important and profitable route is transporting grain, corn, and everything else through Ukrainian ports. Other options, including other ports, are less effective for Ukrainian exports.

Out of these 7 million tons, 5 million go through Greater Odesa’s ports – Odesa, Chornomorsk, and Pivdennyi. Another nearly 1.1 million goes through the Danube ports. By rail, a total of 700,000 tons goes through Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Poland. Only 30,000 tons of these 7 million cross the border through Poland by road.

The issue of Poland’s border blockade was hyped up in the media, creating the impression that if transit through Poland stops, Ukraine’s economy will collapse. This is not true, but the issue is still important.

Poland is protecting its market because Polish farmers typically have small farms, unlike in Ukraine, where farms have thousands of hectares of land. Therefore, the cost of production in Poland is higher.

So, the question is no longer about Ukraine but about those in Poland who want to buy from Ukraine at a lower price.

For Ukraine, this blockade situation is a litmus test from the strategic viewpoint. Ukraine is moving towards the European Union. We need to negotiate with all 27 countries of the EU and cooperate with European institutions, and are now trying to solve this issue precisely within the framework of European integration.

Moreover, we understand that the issue of Ukrainian agricultural exports is now being raised in Poland in the context of elections, first parliamentary and now local. Since farmers and parties associated with them strongly influence the elections, this issue is gaining disproportionate importance.

From the economic perspective, most of our products go through ports. However, resolving export issues with Poland should be used as a step forward towards negotiations with the EU, because it is fundamental. Borders were closed and trucks were blocked, creating huge problems beyond the agricultural sector. This also means losses for Poland.

Similar issues took place during Poland’s EU integration, when Polish farmers entered the German and French markets. I think this is a matter of time. We see that quotas were adopted after negotiations in Brussels, regulating exports of Ukrainian corn, poultry meat, eggs, sugar, and some other categories. These are based on the indicators of 2022-2023 and second half of 2021.

Given that this year, as Ukrainian agricultural sector experts claim, we, unfortunately, do not expect a record harvest, and the ports are currently operating, these quotas will not be critical for Ukraine.

At the same time, the European Union market holds strategic importance for Ukraine. For Ukrainian farmers, European integration is fundamentally crucial.

EP: How about various certificates and norms for Ukrainian exporters? The Poles, in particular, claim that Ukrainian goods do not meet all the standards or don’t have all the necessary permits. What is the position of the Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce regarding this issue?

HC: I am not an expert on quality issues, but we do place this question before our Ukrainian grain producers’ associations and farmers. Ukrainian agricultural products are of very good quality and find demand in all countries. This includes China, which, thanks to the ports, has begun to increase imports from Ukraine again, as well as Italy and Spain. They do not have enough grain, and they are happy to buy it.

This issue shouldn’t be overemphasized. Poland introduced the term “technical grain” for all transit grain, which doesn’t reflect the actual quality. It’s a question for Poland to address. When people hear on television that thousands of tons of technical grain have passed through Poland, they assume it’s a quality issue. However, Ukrainian grain and agricultural products are in high demand worldwide. We supply thousands of tons to EU countries like Italy and Spain. Have their media reported any issues with the quality of Ukrainian grain?

EP: Regarding EU integration, what norms and regulations should Ukraine establish legally to prevent claims of inadequate products? For example, carrier licenses are an issue. What are your thoughts on this?

HC: In general, Ukraine is moving in leaps and bounds towards European integration because Ukrainians learn very quickly and take legal issues very seriously. I talk to our carriers; they do not use any illegal methods to compete with Polish or other carriers. The key issue that arises is the issue of price, but it is lower only due to wages because we buy fuel in Europe at the same prices as they do.

As for other issues, Ukrainians willing to work working according to the same norms as the Poles. Tell us what is needed, and we will compete on equal terms. No one is against this.

People often focus on the present situation, forgetting the past. When Polish carriers began operating extensively in Germany and Italy, Italian and German carriers raised similar concerns. This is a matter of time and Ukraine’s EU integration process. I wouldn’t dramatize the issue. For Polish carriers, who have dominated the European market, the emergence of Ukrainian competitors poses a challenge. After all, no one likes competition.

EP: Polish representatives also argue that when Poland joined the EU in 2004, it did not have access to the labor market in Germany for a certain period, and there were various temporary restrictions. What is your position regarding Ukraine’s integration and the possibility of such temporary restrictions?

HC: First, we understand that Ukraine is the first country in the history of the European Union to be given the green light to start the negotiation process while at war. Second, we are very grateful to the European Union. They helped us by removing restrictions on the road transport of our goods and so on. After two years of war, some quotas are being restored, but at significantly higher levels.

For Ukrainian businesses and citizens, working under wartime conditions is like a real-life, high-level MBA test. Approximately 6 million Ukrainians are currently abroad, mainly in EU countries, with many working there. They are learning about the EU’s workings and realizing that life isn’t perfect anywhere. While wages may be higher in the EU, life in Ukraine is not significantly different, apart from the military threat.

Many European countries, including Poland, may express diplomatic reservations about Ukraine’s integration. However, in practice, they are not opposed to Ukrainian citizens working or living in their countries, as it boosts their GDP.

The real challenge for Ukraine lies in the ongoing mobilization efforts. We need to support our army while facing a shortage of both military and civilian workers. These are overarching issues.

The real problem is that a loss of Ukrainians without EU integration causes a huge danger for Ukraine, creating a lack of both military and civilian workers.Hennadiy Chyzhykov

EP: Do you anticipate full market access for Ukraine upon joining the EU, or could there be restrictions and gradual integration?

HC: We are currently at war, and Europe’s principled stance is crucial for us. We don’t expect our economy and people’s well-being to improve drastically immediately after the war. Rebuilding Ukraine will be a lengthy process. I hope Europe’s solidarity with Ukraine persists, even if quotas remain for key products like poultry, eggs, sugar, and corn. Successful EU integration is fundamental for us.

Quotas on Ukrainian goods can be viewed from different perspectives. One the one hand, they are restrictive and seem to contradict solidarity; on the other hand, they also confirm Ukraine’s strength and competitiveness. It’s better to produce many highly competitive products for the European market than to have nothing to offer.

This situation provides food for thought. Ukrainian businesses have adapted over the past two years, opening Danube ports and seeking new opportunities. If some of our agricultural products face limited demand in Europe, it’s not a major concern; Ukraine has vast markets in Africa, China, and other Asian countries. The crucial point is that we have these products, and there is global demand for them.

Regarding industry, the enemy’s targeting of Ukraine’s energy sector is devastating. However, it presents us with a new path. Ukraine will rebuild its energy sector according to European green energy standards. We’ve already seen investments in solar energy and bioenergy increasing in Ukraine. Thus, war brings not only destruction but also the development of entirely new economic sectors.

I demonstrate to my EU colleagues that during two years of war, I have rarely used cash, relying on digital payments instead. We continue working, we have internet access almost everywhere and continue to digitalize our society. Although our metallurgical plants have been bombed, with only those in Zaporizhzhia and Dnipro remaining, we have abundant ore reserves. We will build new plants focused on green metallurgy, ensuring our competitiveness in terms of carbon emissions in the European market. During my recent visit to Dnipro, I witnessed people creating and developing new businesses despite the proximity to the frontline. Ukraine has immense opportunities.

Before the war, 25% of Ukrainian exports to Germany came from German automotive giants with production facilities in Ukraine for various car parts. I believe Ukraine will become a significant industrial site for the EU.

Ukraine will continue to be a major food supplier, but large European processing companies will likely realize the benefits of producing goods within our country rather than transporting grain to Italy or Spain.

As we close one chapter, we will open a completely new one. Our top priority is to preserve our people and maintain our sovereignty.

EP: Regarding the upcoming negotiations, how long do you think they should take before Ukraine joins the EU?

HC: Both Ukraine and the EU are interested in ensuring that Ukraine aligns its laws with EU rules as quickly as possible. The Office of European Integration reports that we have already harmonized nearly 90% of the documents in many areas. While the remaining 10% is the most crucial, we will continue moving in this direction. The timeline depends on the end of the war. My optimistic forecast is around 5-7 years, contingent upon our results and how quickly we can achieve victory and continue working in a peaceful country. EU countries understand that it will be more challenging without Ukraine. As a large, significant, and powerful nation, it is better for the EU to have Ukraine as a member.

Related:

- “Most countries protect their farmers.” Poland’s top trade economist on why border blockade keeps going

- Ukraine gears up for EU accession talks

- EU set to unlock €50 billion in aid following endorsement of Ukraine’s reform plan

- Ukraine passes anti-corruption laws to advance EU integration