What makes Russian spies tick? World’s largest declassified KGB archive, in Ukraine, tells all

Russian spies don't innovate - they study and update decades-old KGB manuals, says Andriy Kohut, who oversees the world's largest collection of declassified Soviet intelligence files that Moscow mistakenly abandoned in Ukraine.

Ukraine holds the world’s largest declassified KGB archive, a vast collection of unique materials stored by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). According to archive director Andriy Kohut, these documents fundamentally challenge Western perceptions of the USSR.

Kohut points to a striking paradox in Western academia: scholars often acknowledge the Soviet regime’s brutality while maintaining that Ukrainians and Russians “peacefully coexisted.” This peaceful coexistence, he argues, is a myth. Russians systematically eliminated Ukrainians through the NKVD and KGB – a pattern that continues today with FSB operations in occupied territories and missile strikes on unoccupied areas.

Instead of accepting Russian historical narratives, Kohut urges Western researchers to examine authentic period documents revealing the mindset of the system’s enforcers – the KGB and NKVD operatives. Understanding their patterns of thinking is crucial, he says, as their successors in the Russian FSB operate in similar ways today.

Yet a major obstacle remains: the archive lacks English translation, significantly limiting Western academic access. There’s hope for change, though, as the current SBU archive director speaks English and participates in Western academic programs.

In an interview with journalist Olha Aivazovska for Civil Network OPORA’s Power of Choice project, Kohut discusses what these archives contain and how researchers can access them.

Q: Do the KGB archives contain enough information to show the West the origins of Russia’s genocidal war against Ukraine?

Andriy: The myth of friendly coexistence stems from a colonial perspective. Western literature and documentaries were created through a lens that saw others as mere variants of Russians. Challenging this view requires access to archival documents.

While the ongoing war prevents researchers from visiting Ukraine, we’re solving this through digitization. Ukraine is actively creating digital copies and English-language guides to make these materials accessible – a crucial step for any meaningful historical reassessment.

Our unique archive is the world’s largest open collection of KGB documents. Unlike in the Baltic states, where Russia removed documents before the Soviet collapse, Moscow left Ukraine’s archives intact, believing Kyiv would remain compliant. This gives us an extensive collection of repression records, orders, instructions, and documents from various Soviet security agencies (KGB, NKVD, Cheka), along with training manuals and statistics.

We tell researchers: “These materials will transform your understanding of what the Soviet Union was, what the Russian Empire was, and what Russia is today.”

Q: Who has access to the archive?

Andriy: Our reading rooms are closed due to constant air raids and safety concerns. However, we provide digital copies upon request. While it’s not the same as handling original documents, it ensures access to information. Most requests come from relatives searching for information about their repressed family members.

We’ve already seen successful cases of changing Western perspectives. Take the recognition of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 – Stalin’s man-made famine that killed millions of Ukrainians – as genocide by various national parliaments. Major research centers at Harvard and the University of Alberta now focus on Holodomor studies, with established publishing opportunities and funding. We need a similar academic ecosystem to reexamine Russia’s imperial past.

Q: Before the full-scale invasion, there were reports about Russian FSB blacklists of Ukrainian activists, journalists, and political figures marked for elimination – which they later carried out in occupied territories. Are there historical parallels with KGB operations?

Andriy: In 2021, we published research with Polish partners revealing identical tactics from 1939. When the Soviet Union was Nazi Germany’s ally, Stalin methodically prepared lists for repression in Poland, targeting officials, journalists, and civic leaders. What required extensive intelligence work in 1939 is now simpler with online data. The FSB still follows this playbook, just with updated technology.

The archives also reveal patterns of agent infiltration. During the “voluntary” population exchange between Poland and Soviet Ukraine, the NKVD planted agents among relocators. We see similar tactics today—when hundreds of thousands fled Russia to avoid mobilization, the FSB likely planted agents among them, including those now posing as “Russian opposition” in the West.

The KGB archives are crucial because they reveal how FSB officers think. They don’t innovate—they study old methods and adapt them to modern conditions. Many current news stories create a sense of déjà vu—the tactics remain unchanged, only technologically updated.

Q: The cult of victory in WWII has become a cornerstone of Russia’s new ideological framework, particularly in justifying the “denazification” of Ukraine as a pretext for the full-scale invasion. How did this myth about “Ukrainian Nazis” evolve?

Andriy: It began by classifying everything about the so-called Great Patriotic War (WWII). Russia restricted access to historical documents while constructing a simple narrative: fascists versus anti-fascists. Once established, this framework could label anyone as fascist – Georgians, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Poles – the template remains, only the target changes.

The KGB ran extensive propaganda campaigns in the West, particularly in North America, promoting the “Ukrainian = fascist” equation. Russia still weaponizes World War II history this way. Recently, when a Russian consulate in Canada claimed the SS Galicia Division proved the Ukrainian diaspora’s “fascist” nature, I was studying late-period KGB documents describing an identical operation through the Toronto Star. Reading these, it’s impossible to tell whether it’s 1987, 2017, or 2022.

These tactics succeeded not just because of Russia’s resources and cultivated cultural prestige but also because, until the full-scale invasion, Western researchers saw only Russia and its periphery. While Russia’s evident crimes now force some reassessment, challenging these deeply rooted misconceptions requires sustained effort.

Q: How has Western academic discourse shifted since the full-scale invasion?

Andriy: Access to KGB archives has become crucial in compelling Western academia to reassess its perspectives. Before February 2022, Ukrainian historians were often dismissed as nationalist-biased; now, they’re recognized as essential voices in discussions of decolonization. This marks a dramatic shift from decades when Ukrainian scholars were relegated to an intellectual ghetto, viewed merely as Soviet refugees with nationalist tendencies.

Today, young researchers are actively learning Ukrainian and studying the roots of Ukraine’s resistance. The challenge now is ensuring Ukrainian voices are represented at all levels—government, academic, and cultural. This is a stark change from early 2022 when many questioned whether Ukraine would resist Russia despite its continuous resistance since 2014 and throughout Soviet times.

Q: While Russia weaponizes WWII history to justify its actions within Ukraine, its aggressive tactics extend far beyond Ukrainian borders. Russia’s poisonings of Alexander Litvinenko in London, Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, and Alexei Navalny in Berlin show a pattern of political murders on Western soil. How far back does this practice of eliminating opponents abroad go?

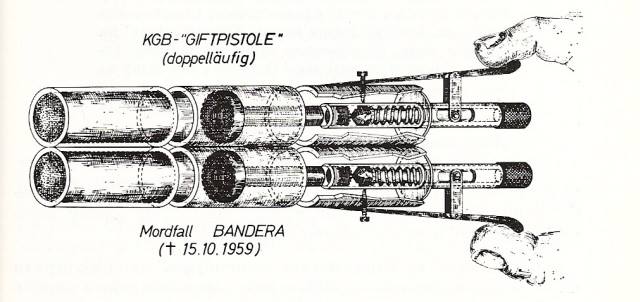

Our archive documents reveal this methodology of overseas assassinations has deep historical roots. The 1959 killing of Stepan Bandera [a controversial Ukrainian independence leader during and after WWII – ed.] in Munich is telling—KGB agent Bohdan Stashynsky used an untraceable poison gas weapon, a fact only revealed after his defection. The Soviets masked it as an internal conflict among Ukrainian nationalists, much like today’s suspicious deaths of Russian opposition figures abroad.

The KGB archives also show how, decades after World War II, the Soviet Union hunted and kidnapped Ukrainian political figures from Austria and West Germany. Our book “Woe to the Vanquished” details how these targets, many never Soviet citizens, were forcibly returned for show trials. When Putin today says Russia has no borders, he’s following this documented pattern—from Bandera’s time to now, neither Western jurisdiction nor geography protects against Russian retribution.

Q: Beyond assassinations abroad, what other methods has Russia historically used to punish its opponents?

Andriy: One of the most chilling methods connects directly to today’s headlines – the targeting of children. The ICC’s arrest warrant for Putin over Ukrainian child abductions isn’t a new tactic but rather an expansion of Soviet-era practices. Back then, the regime would take children from political opponents – whether Ukrainian resistance fighters, Polish dissidents, or others – and place them with Russian families to erase their original identity. The children of UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army – a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary organization that fought against both Nazi Germany and Soviet forces during and after WWII – ed.] commander Roman Shukhevych are a stark example. What was once selective during Soviet times has become systematic under Putin’s Russia.

Another enduring tool is Siberian deportation – a practice stretching from the Romanov Empire through today. The same vast “white spot” on the map that once swallowed Polish insurgents and Ukrainian dissidents is now openly discussed by Kremlin officials as a destination for Ukrainians who refuse to identify as Russians. This isn’t theoretical – the archives show exactly how this worked before.

What’s particularly troubling is how these crimes went unpunished historically. After World War II, the Soviet Union escaped accountability for its crimes against humanity, partly because it was an Allied power but also because many failed to recognize it as an empire. Today, Russia continues this pattern, expertly manipulating narratives while Western partners, accustomed to diplomatic honesty, struggle to grasp that the Kremlin never tells the truth.

The international community’s defense of human rights rings hollow against its actions. Western cooperation—through energy dependence, technology transfers, banking access, and continued trade—has enabled Russia’s repressive apparatus. While Russia perfected methods of oppression, global economic ties provided both resources and implicit approval for their implementation.

Q: Why wasn’t the Soviet Union punished for its crimes against humanity after World War II?

Andriy: Two critical factors protected Soviet impunity: its status as an Allied victor and, more fundamentally, the West’s failure to recognize its colonial nature. At Stanford, when historian Amir Weiner, who studies Soviet state violence and empire, asks his graduate students whether they consider the USSR an empire, their recognition of this fact represents a major shift in understanding.

The Soviet approach to truth illustrates this colonial deception perfectly: During Khrushchev’s rehabilitation of Stalin’s victims, the regime told families their relatives died from natural causes in prison—heart attacks, tuberculosis, strokes—rather than admitting they were executed. This lie held until the USSR’s collapse.

Just as the Soviet Union was never truly a “union,” today’s Russian Federation isn’t actually federal. It’s a colonial empire that masterfully manipulates terminology, crafting different truths for different audiences while maintaining colonial control.

Q: What about the possibility of Russia’s collapse through resistance from its indigenous peoples?

Andriy: This is crucial for understanding Russia’s future. There are about 20 indigenous peoples within Russia, though their numbers are small and further diminished by the Kremlin’s deliberate strategy of sending them first to die in Ukraine.

While we often discuss potential Russian collapse, the real question is whether these colonized peoples can develop a decolonial consciousness and resistance. The challenge is severe—unlike the Soviet era’s dissident movement, today’s Russia lacks genuine anti-imperial voices. What’s labeled as “liberal Russian opposition” typically just repackages imperial narratives, merely objecting to Putin while supporting continued colonial domination.

We must study these peoples’ languages and cultures, understand their potential for resistance, and identify authentic voices calling for decolonization. Without their active push for self-determination, they risk remaining colonial subjects sacrificed in Russia’s imperial wars. The key isn’t whether Russia will collapse but whether its colonized peoples will find the strength to reclaim their sovereignty.

***

Ukraine’s handling of Soviet KGB archives reveals a stark contrast in confronting the past. Since 2015, after the Euromaidan protests, Ukraine has maintained the most liberal archive access policy among former Soviet states. The scale is immense—the KGB files would stretch 7 kilometers if arranged in a single row.

Access to these archives is remarkably straightforward. Researchers need only provide basic information about their subject, and there are no access or document copying fees. The essential requirements are fundamental personal data: full name (including patronymic), date and place of birth, and residence at the time of arrest or repression. Given historical complexities—empire collapses, border changes, occupations—names often have multiple variants worth investigating.

Requests can be submitted electronically or by mail, and responses are guaranteed within a month. All contacts and instructions for submitting requests can be found here.

The contrast is clear: Russia still keeps its Soviet archives classified.

Read more:

- Supreme power of Putin’s FSB. Part 1: how the Soviet KGB became Russia’s FSB

- KGB archives document Red Army’s atrocities against Ukrainian village in USSR after 1945

- 10 things the KGB didn’t want you to know about Chernobyl

- The KGB massacred thousands of Poles in 1940 Kharkiv, declassified files reveal

- Three fundamentals of collective Putin’s paranoia “ideology”

You could close this page. Or you could join our community and help us produce more materials like this.

We keep our reporting open and accessible to everyone because we believe in the power of free information. This is why our small, cost-effective team depends on the support of readers like you to bring deliver timely news, quality analysis, and on-the-ground reports about Russia's war against Ukraine and Ukraine's struggle to build a democratic society.

A little bit goes a long way: for as little as the cost of one cup of coffee a month, you can help build bridges between Ukraine and the rest of the world, plus become a co-creator and vote for topics we should cover next. Become a patron or see other ways to support.