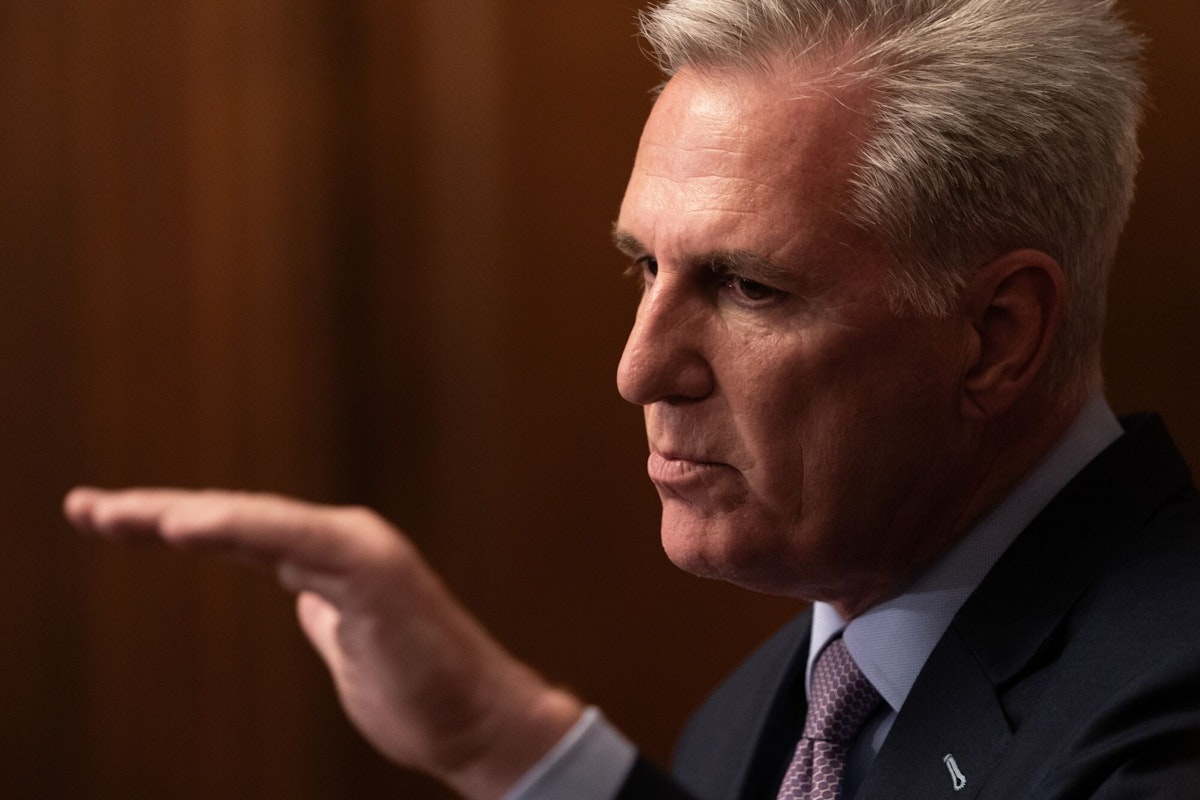

Who Did in Kevin McCarthy? Maybe Not Gaetz. Maybe Not Even Trump.

Did bond vigilantes kill Kevin McCarthy? Before you answer, “Of course they didn’t,” hear me out. Let’s grant that McCarthy was pushed out of the House speakership by a Republican caucus, or anyway a toxic sliver of it, driven mad by some combination of opportunism, nihilism, Trumpism, and personal loathing for McCarthy. This last factor was, I think, the most important (as it usually is). Here’s how Bill Thomas, McCarthy’s mentor and Republican predecessor representing California’s 20th congressional district, described McCarthy to The New Yorker shortly before McCarthy was elected speaker (on the, ahem, fifteenth ballot): “Kevin basically is whatever you want him to be. He lies. He’ll change the lie, if necessary. How can anyone trust his word?”TNR’s Alex Shephard expresses a similar view, calling McCarthy’s ouster “a pathetic moment and a deserved one.” I can’t disagree. In May I plugged McCarthy into Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “stag hunt” game-theory problem, and it led inexorably to the conclusion that McCarthy would be “gone by Christmas.” I should have said “Columbus Day.”Still, when you fire your party leader, you’re supposed to have a more high-minded reason than “I just can’t stand that prick, never could.” The nominal reason Representative Matt Gaetz, Republican of Florida, gave for initiating McCarthy’s removal was the national debt. “I don’t think removing Kevin McCarthy is chaos,” Gaetz said Tuesday. “I think $33 trillion in debt is chaos. I think that facing a $2.2 trillion annual deficit is chaos.” McCarthy lost the speakership because eight members of his caucus voted against him: Gaetz and Representatives Andy Biggs of Arizona, Ken Buck of Colorado, Tim Burchett of Tennessee, Eli Crane of Arizona, Bob Good of Virginia, Nancy Mace of South Carolina, and Matt Rosendale of Montana. These were McCarthy’s executioners, and every last one of them cited government debt as the reason. Well sure, you say. Republicans always complain about government debt—except, of course, when there’s a Republican in the White House. But this time it wasn’t just a bunch of right-wing fair-weather fiscal conservatives who were playing Chicken Little. This time the bond market was too. The bond market is a little like the pilot light on your furnace. You only remember that it exists when it flickers out. My onetime Wall Street Journal colleague David Wessel, who runs the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, told me it “drives me nuts sometimes” that the only market indicator the press usually reports on is the stock market, when it’s really the bond market that affects normal people by raising or lowering the price of car loans and mortgages. Investors’ current flight from the bond market, which has pushed up 10-year Treasury bond yields to 16-year highs, is, Wessel said, “probably a more significant event in the economy than the stock market moving 500 points.”To extend the pilot-light metaphor: The bond market has flickered out. There’s a huge sell-off going on, and, as Nick Timiraos wrote Tuesday in The Wall Street Journal, “the exact triggers for the move are unclear.”For awhile the bond market made sense. The rates on 10-year Treasuries rose in 2022 from about 1.5 percent in January to a high of 4.1 percent in October. That was because inflation was rising, prompting the Fed to jack up interest rates. When interest rates are high, borrowing gets expensive, and so people borrow less. What happened next also made sense. For the first four months of 2023, as it became evident that inflation was coming down (and that, as a consequence, the Fed wouldn’t likely keep raising interest rates much longer), Treasury yields leveled off. But starting in mid-May, the bond market stopped making sense. Treasury yields resumed their climb, even though inflation was continuing to come down and the Fed was pretty obviously preparing to cut interest rates in 2024. According to Timiraos, “The likeliest causes appear to be a combination of expectations of better U.S. growth,” which will increase demand for borrowing, “and concern that huge federal deficits are pressuring investors’ capacity to absorb so much debt.” For four decades, the chief economic worry about large federal deficits has been that federal borrowing will “crowd out” private spending needed to make the economy grow. But evidence of such crowding out has seldom appeared. The last time it did was in 1994, when President Bill Clinton, who’d campaigned promising a fiscal stimulus, instead raised taxes and cut spending to bring the deficit down and calm the U.S. bond markets, which ended up losing $1 trillion in value that year, half in Treasuries and the rest divided between corporate and municipal bonds. The Great Bond Massacre, as it came to be known, prompted political adviser James Carville to grumble, “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter.

Did bond vigilantes kill Kevin McCarthy? Before you answer, “Of course they didn’t,” hear me out.

Let’s grant that McCarthy was pushed out of the House speakership by a Republican caucus, or anyway a toxic sliver of it, driven mad by some combination of opportunism, nihilism, Trumpism, and personal loathing for McCarthy. This last factor was, I think, the most important (as it usually is). Here’s how Bill Thomas, McCarthy’s mentor and Republican predecessor representing California’s 20th congressional district, described McCarthy to The New Yorker shortly before McCarthy was elected speaker (on the, ahem, fifteenth ballot): “Kevin basically is whatever you want him to be. He lies. He’ll change the lie, if necessary. How can anyone trust his word?”

TNR’s Alex Shephard expresses a similar view, calling McCarthy’s ouster “a pathetic moment and a deserved one.” I can’t disagree. In May I plugged McCarthy into Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “stag hunt” game-theory problem, and it led inexorably to the conclusion that McCarthy would be “gone by Christmas.” I should have said “Columbus Day.”

Still, when you fire your party leader, you’re supposed to have a more high-minded reason than “I just can’t stand that prick, never could.” The nominal reason Representative Matt Gaetz, Republican of Florida, gave for initiating McCarthy’s removal was the national debt. “I don’t think removing Kevin McCarthy is chaos,” Gaetz said Tuesday. “I think $33 trillion in debt is chaos. I think that facing a $2.2 trillion annual deficit is chaos.”

McCarthy lost the speakership because eight members of his caucus voted against him: Gaetz and Representatives Andy Biggs of Arizona, Ken Buck of Colorado, Tim Burchett of Tennessee, Eli Crane of Arizona, Bob Good of Virginia, Nancy Mace of South Carolina, and Matt Rosendale of Montana. These were McCarthy’s executioners, and every last one of them cited government debt as the reason.

Well sure, you say. Republicans always complain about government debt—except, of course, when there’s a Republican in the White House. But this time it wasn’t just a bunch of right-wing fair-weather fiscal conservatives who were playing Chicken Little. This time the bond market was too.

The bond market is a little like the pilot light on your furnace. You only remember that it exists when it flickers out. My onetime Wall Street Journal colleague David Wessel, who runs the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, told me it “drives me nuts sometimes” that the only market indicator the press usually reports on is the stock market, when it’s really the bond market that affects normal people by raising or lowering the price of car loans and mortgages. Investors’ current flight from the bond market, which has pushed up 10-year Treasury bond yields to 16-year highs, is, Wessel said, “probably a more significant event in the economy than the stock market moving 500 points.”

To extend the pilot-light metaphor: The bond market has flickered out. There’s a huge sell-off going on, and, as Nick Timiraos wrote Tuesday in The Wall Street Journal, “the exact triggers for the move are unclear.”

For awhile the bond market made sense. The rates on 10-year Treasuries rose in 2022 from about 1.5 percent in January to a high of 4.1 percent in October. That was because inflation was rising, prompting the Fed to jack up interest rates. When interest rates are high, borrowing gets expensive, and so people borrow less.

What happened next also made sense. For the first four months of 2023, as it became evident that inflation was coming down (and that, as a consequence, the Fed wouldn’t likely keep raising interest rates much longer), Treasury yields leveled off.

But starting in mid-May, the bond market stopped making sense. Treasury yields resumed their climb, even though inflation was continuing to come down and the Fed was pretty obviously preparing to cut interest rates in 2024. According to Timiraos, “The likeliest causes appear to be a combination of expectations of better U.S. growth,” which will increase demand for borrowing, “and concern that huge federal deficits are pressuring investors’ capacity to absorb so much debt.”

For four decades, the chief economic worry about large federal deficits has been that federal borrowing will “crowd out” private spending needed to make the economy grow. But evidence of such crowding out has seldom appeared. The last time it did was in 1994, when President Bill Clinton, who’d campaigned promising a fiscal stimulus, instead raised taxes and cut spending to bring the deficit down and calm the U.S. bond markets, which ended up losing $1 trillion in value that year, half in Treasuries and the rest divided between corporate and municipal bonds. The Great Bond Massacre, as it came to be known, prompted political adviser James Carville to grumble, “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

We may now be experiencing another Great Bond Massacre, or at least a Little Bond Massacre. If so, why now? Granted, the deficit, which is projected this year to be about $2 trillion, is much higher as a percentage of gross domestic product (5.8 percent) than it was the year Clinton entered office (3.7 percent). But two years ago the deficit was nearly $3 trillion, or almost 12 percent of GDP, and the bond market didn’t raise a peep. Why a bond sell-off now?

Possibly because the Chinese are flooding the bond market by selling off Treasuries to prop up the yuan. But if that started the stampede, what’s continuing it? Peter Gosselin, a former national economics reporter for the Los Angeles Times, suggested to me that investors may be suffering the same vague anomie that two years ago had them anticipating a wage-price spiral that never came, and that last year had them anticipating a recession that never came. There is, Gosselin said, an “ill-formed sense that something fundamental is awry with the world and we don’t quite know what it is but we’re going to keep aiming our gun at different things until we hit the right target.” The irony is that the bond sell-off may achieve what the Fed has managed to avoid—it may choke off economic growth so much that it crashes the economy into recession. If that happens, the cure will at last have found a disease.

How might bond vigilantes have influenced Matt Gaetz’s House assassination caucus? Like Carville, I’m susceptible to believing bond traders control everything. That’s conspiratorial, I know, but if you believe that America is ruled by Ivy League meritocrats, as many respectable thinkers do, then you must ask yourself what these meritocrats do all day. Almost nobody in my Harvard graduating class of 1980 did what Harvard President James Bryant Conant and Henry Chauncy, a Harvard assistant dean who went on to create the Educational Testing Service, envisioned Harvard graduates doing when, during the 1930s and 1940s, they assembled the machinery of the modern meritocracy. Conant and Chauncy thought they were creating a class of public philosophers who would guide American government into the twenty-first century. But almost nobody I knew in college went to work for the government. You know what they did instead? They became bond traders. That was 43 years ago, but things don’t appear to have much changed. Over the past 20 years, surveys have shown anywhere from one-third to one-half of all Harvard graduates went directly into finance or management consulting. If Harvard (and Yale and Princeton and Stanford) governs America, then it’s hard to escape the conclusion that America is governed by a bunch of bond traders.

The phrase “bond vigilantes” was coined 40 years ago by investment strategist Ed Yardini, who wrote about the budget deficit: “If the fiscal and monetary authorities won’t regulate the economy, the bond investors will. The economy will be run by vigilantes in the credit markets.” Yardeni is also the guy who predicted computers would go haywire on January 1, 2000, so take his prophecies with a grain of salt. But the bond vigilantes certainly bitch-slapped James Carville in 1994. Are they curb-stomping Kevin McCarthy now?

Yardeni says the bond vigilantes are actually coming for Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and President Joe Biden. “The bond yield has gone vertical in recent weeks,” he wrote Tuesday in the Financial Times,

jumping to 4.80 per cent on Tuesday. If it continues to soar up to 5 per cent or higher, Yellen should meet Biden to explain that the bond vigilantes are about to trigger a crisis that could derail his chances of winning another term.

But this is based on a misconception, of which Yardeni ought to be aware but clearly isn’t. Budget deficits are not the fault of Democrats who can’t control spending. Budget deficits are the fault of Republicans who can’t control spending and also can’t raise taxes (indeed, usually cut them). When Clinton left office, the budget was in surplus. For the past four decades it’s been Republican presidents (Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Donald Trump) who’ve expanded the deficit and Democrats (Clinton, Barack Obama, Joe Biden) who’ve shrunk it. The only exception was George H.W. Bush, a Republican who lowered the deficit by raising taxes after pledging (“Read my lips”) not to, and may have lost the 1992 election as a result.

Republicans, including McCarthy, talk a good game about cutting spending, but (like Democrats) they’ve concluded it’s political suicide to cut Medicare and Social Security. Meanwhile (unlike Democrats), Republicans only ever increase defense spending. That leaves Republicans engaged in an endless absurd pantomime of trying to cut “domestic discretionary spending,” which is only about 13 percent of the entire federal budget.

The path to fiscal solvency is to increase taxes and to cut spending on defense, Medicare, and Social Security. Democrats are willing, at least in theory, to raise taxes; I say “in theory” because Biden’s proposed all sorts of tax increases that have mostly been rejected by congressional Democrats. Which is a problem.

But congressional Republicans only ever cut taxes and address spending by trying to slash that puny 13 percent of federal spending to the point of crippling the function of federal agencies. The argument between McCarthy and the Gaetz assassination caucus (to the admittedly limited extent it was a coherent argument) was about how much of that 13 percent to slash. The argument is stupid and pointless, but McCarthy could never move the House past it, so he had to go.

The bond vigilantes’ tool for removing McCarthy was the eight Republican rebels, who probably don’t know much about the bond market but have constituents or political campaign contributors who do. Or maybe they overheard something on Fox Business or CNBC. They didn’t need a lot of encouragement. The eight rebels did the bond vigilantes’ bidding, but they are not the bond vigilantes’ ally. That’s because Gaetz and company’s fiscal conservatism rings hollow. The bond sell-off will therefore continue. Biden is the bond vigilantes’ ally, to the limited extent anybody is. He wants to raise taxes. Wall Street wants to raise taxes! Only a Democrat can do that. I don’t think our bond-trader overlords give a damn whether the taxes are progressive or not, so we might as well make them progressive. Let’s do as the bond market tells us and raise taxes. It worked for Clinton, and it can work for Biden too.