Why Biden Must Fire the Head of the FDIC

An independent investigation has now confirmed allegations raised last November by a Wall Street Journal report that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—the government regulator that insures bank deposits—is (as the Journal put it) “a toxic work environment” and “sexualized boys’ club” that “enabled and failed to punish bad behavior.” The misbehavior predated by at least 10 years the current chairmanship of Martin Gruenberg, who took the reins in January 2023. But it continued under Gruenberg, who also has been on the FDIC’s board since 2005 and, from November 2012 to mid-2018, served a previous term as chairman. And yet, at a hearing of the House Financial Services committee in November, Gruenberg denied he was previously aware, even “as a general matter,” of the allegations in the Journal report. That’s reason enough for President Joe Biden to fire him. He probably should have done so before Thanksgiving.The Journal investigation, by Rebecca Ballhaus, was devastating. Here’s the lede:A male Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. supervisor in San Francisco invited employees to a strip club. A supervisor in Denver had sex with his employee, told other employees about it and pressed her to drink whiskey during work. Senior bank examiners texted female employees photos of their penises.All of the men remained employed at the agency. One woman who’s since left the FDIC said several of her male colleagues discussed, while staring at her, how women should use sex to get ahead. A hotel near Washington where the FDIC’s out-of-town bank examiners stay during Financial Institutional Specialist training became such a party hub that one participant wrote in an Instagram account: “If you haven’t puked off the roof, were you ever really a FIS?”In 2020 the FDIC’s inspector general reported that 8 percent of respondents to an agency survey taken the year before reported experiencing sexual harassment. By government-wide standards, that was low; across all agencies the average was 14 percent. But of that 8 percent, 38 percent reported they didn’t report the incident “for fear of retaliation.” That ought to have set off alarm bells. Instead, the FDIC replied to the inspector general’s office that it already had “a robust anti-harassment program,” adding, “we respectfully disagree with the [inspector general’s] conclusion that the FDIC’s Anti-Harassment Program is ‘inadequate.’” That claim has not aged well.Gruenberg was not yet chairman when the inspector general report was released; his Republican predecessor was. But when he became chairman in 2023 the agency was on notice that it had a sexual harassment problem. One month into Gruenberg’s term, another inspector general report said resignations from FIS training had more than doubled during the previous three years. You didn’t have to be a genius to connect these dots. Had Gruenberg done so, the allegations later reported by the Journal would not have taken him by surprise.The FDIC-commissioned independent investigation, conducted by the law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, confirms that sexual harassment at the agency is out of control. More than 500 people called in to Cleary Gottlieb’s hotline—and the FDIC employs only about 6,000. The incidents callers described went mostly unreported through official channels, for fear of retaliation. “Everyone knows that if you spoke out, you would get a bullseye on [your] back,” one FDIC employee told the commission. “The few people who did speak up are no longer at the agency.” Making sure managers don’t retaliate against employees who report sexual harassment is the bare minimum that a federal agency can do in such circumstances.In a follow-up to her first Journal story published a few days later, Ballhaus reported that Gruenberg had an anger-management problem. During his two decades at the FDIC, Ballhaus wrote, Gruenberg “berated and cross-examined staffers, questioned their loyalty and accused them of keeping information from him.” When Gruenberg was FDIC vice chairman in 2008, his temper occasioned an FDIC investigation, something that escaped his memory when he testified last November before Congress. “Have you ever been investigated for inappropriate conduct during your time at the FDIC?” Gruenberg was asked. “No,” he replied. He corrected the record only after the Journal inquired about the discrepancy.A word about bosses who throw temper tantrums. I take this complaint with a grain of salt, having survived working for screamers in the past, one of them a beloved mentor. Yes, yelling at employees is a bad—and predominantly male—managerial habit, and these patriarchs ought to show more self-control. But woman bosses have been known to throw tantrums too. One of them might make a fine president of the United States. Another, Sheila Bair, was the Republican-appointed FDIC chair from 2006 to 2011. Bair was one of very few government officials whose reputation was enhanced rather than diminished by the 2008 financial cri

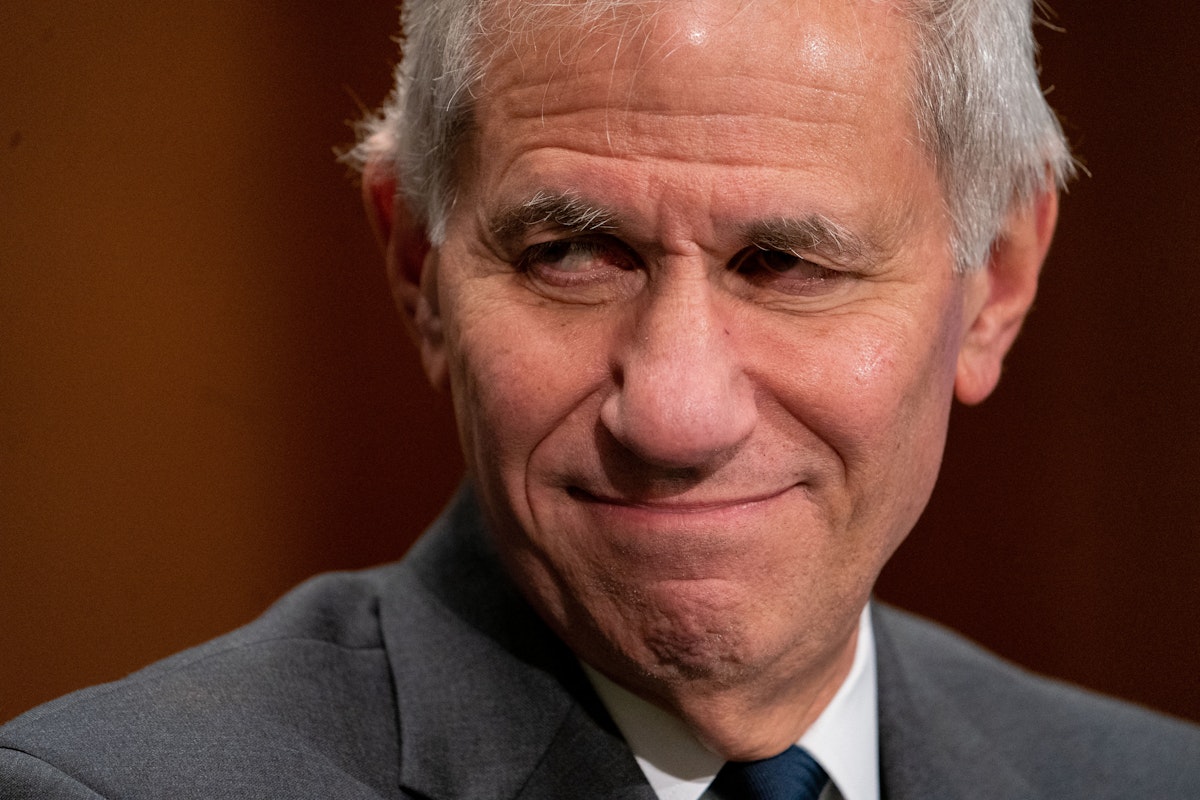

An independent investigation has now confirmed allegations raised last November by a Wall Street Journal report that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—the government regulator that insures bank deposits—is (as the Journal put it) “a toxic work environment” and “sexualized boys’ club” that “enabled and failed to punish bad behavior.” The misbehavior predated by at least 10 years the current chairmanship of Martin Gruenberg, who took the reins in January 2023. But it continued under Gruenberg, who also has been on the FDIC’s board since 2005 and, from November 2012 to mid-2018, served a previous term as chairman. And yet, at a hearing of the House Financial Services committee in November, Gruenberg denied he was previously aware, even “as a general matter,” of the allegations in the Journal report. That’s reason enough for President Joe Biden to fire him. He probably should have done so before Thanksgiving.

The Journal investigation, by Rebecca Ballhaus, was devastating. Here’s the lede:

A male Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. supervisor in San Francisco invited employees to a strip club. A supervisor in Denver had sex with his employee, told other employees about it and pressed her to drink whiskey during work. Senior bank examiners texted female employees photos of their penises.

All of the men remained employed at the agency.

One woman who’s since left the FDIC said several of her male colleagues discussed, while staring at her, how women should use sex to get ahead. A hotel near Washington where the FDIC’s out-of-town bank examiners stay during Financial Institutional Specialist training became such a party hub that one participant wrote in an Instagram account: “If you haven’t puked off the roof, were you ever really a FIS?”

In 2020 the FDIC’s inspector general reported that 8 percent of respondents to an agency survey taken the year before reported experiencing sexual harassment. By government-wide standards, that was low; across all agencies the average was 14 percent. But of that 8 percent, 38 percent reported they didn’t report the incident “for fear of retaliation.” That ought to have set off alarm bells. Instead, the FDIC replied to the inspector general’s office that it already had “a robust anti-harassment program,” adding, “we respectfully disagree with the [inspector general’s] conclusion that the FDIC’s Anti-Harassment Program is ‘inadequate.’” That claim has not aged well.

Gruenberg was not yet chairman when the inspector general report was released; his Republican predecessor was. But when he became chairman in 2023 the agency was on notice that it had a sexual harassment problem. One month into Gruenberg’s term, another inspector general report said resignations from FIS training had more than doubled during the previous three years. You didn’t have to be a genius to connect these dots. Had Gruenberg done so, the allegations later reported by the Journal would not have taken him by surprise.

The FDIC-commissioned independent investigation, conducted by the law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, confirms that sexual harassment at the agency is out of control. More than 500 people called in to Cleary Gottlieb’s hotline—and the FDIC employs only about 6,000. The incidents callers described went mostly unreported through official channels, for fear of retaliation. “Everyone knows that if you spoke out, you would get a bullseye on [your] back,” one FDIC employee told the commission. “The few people who did speak up are no longer at the agency.” Making sure managers don’t retaliate against employees who report sexual harassment is the bare minimum that a federal agency can do in such circumstances.

In a follow-up to her first Journal story published a few days later, Ballhaus reported that Gruenberg had an anger-management problem. During his two decades at the FDIC, Ballhaus wrote, Gruenberg “berated and cross-examined staffers, questioned their loyalty and accused them of keeping information from him.” When Gruenberg was FDIC vice chairman in 2008, his temper occasioned an FDIC investigation, something that escaped his memory when he testified last November before Congress. “Have you ever been investigated for inappropriate conduct during your time at the FDIC?” Gruenberg was asked. “No,” he replied. He corrected the record only after the Journal inquired about the discrepancy.

A word about bosses who throw temper tantrums. I take this complaint with a grain of salt, having survived working for screamers in the past, one of them a beloved mentor. Yes, yelling at employees is a bad—and predominantly male—managerial habit, and these patriarchs ought to show more self-control. But woman bosses have been known to throw tantrums too. One of them might make a fine president of the United States. Another, Sheila Bair, was the Republican-appointed FDIC chair from 2006 to 2011. Bair was one of very few government officials whose reputation was enhanced rather than diminished by the 2008 financial crisis, and rightly so. But apparently Bair had some anger-management issues: Underlings nicknamed her “She Bair.” We are all of us flawed human beings, managers too, and getting yelled at by the boss once in awhile does not violate anybody’s human rights. (Nor should a boss punish an employee who occasionally yells at him.)

But when the boss’s temper becomes so uncontrollable that employees avoid interacting with him, that’s a different matter. This was the case with Gruenberg, the Journal’s Ballhaus reported, and the independent commission went further, suggesting Gruenberg’s temper made employees especially reluctant to disagree with him or deliver bad news:

A number of executives … noted that, although it ultimately did not prevent them from reporting news as necessary, staffers fretted about and delayed delivering news that they feared would upset Chairman Gruenberg, and that his reactions did have a “chilling impact” on open communications.

Like, for example, information about the agency’s problem with sexual harassment? I find unpersuasive the cited executives’ caveat that they never, ultimately, withheld information from Gruenberg. What executive would ever admit to keeping the boss in the dark? A central tenet of my beloved screaming mentor, Washington Monthly founder Charles Peters, was that organizations die when the bad news doesn’t travel up. That seems to be the case here.

Dismissing Gruenberg creates some difficulties. If Biden fires him (unlike at other regulatory agencies, there are no legal obstacles to him doing so), Gruenberg will be replaced by the vice chair, Travis Hill, a Trump appointee who has voted against higher capital standards for banks and, according to an article Robert Kuttner of The American Prospect published last November, frequently “parroted industry talking points.” Kuttner isn’t the only one to observe that the FDIC, which once operated in a fairly collegial and reassuringly boring manner, has become yet another battlefield where hyperpartisan Republicans wage total war. “According to my sources,” Kuttner wrote, “many of the details in the Journal piece began with tips fed to the Journal reporter by Republican FDIC officials and holdover staff.”

Kuttner probably has good sources; in the 1970s he was chief investigator for the Senate Banking Committee. He also knows banking regulation much better than I do, and over the years he’s gotten right many things I got wrong. I asked Kuttner by email Wednesday whether the Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton report changed his mind. His reply:

The Republicans on the FDIC got control of the investigation and spent a lot of money on a fancy law firm to demonstrate the need for Gruenberg’s resignation. The report considered that course and expressly did not call for him to resign. There was a Republican chair for three years after the IG report laid a lot of this out, and she did nothing. Gruenberg obviously should have acted but this doesn’t rise to a case for him to resign. He is obviously chastened and will surely act now.

That the fancy law firm stopped short of calling for Gruenberg’s resignation makes me wonder how much control FDIC Republicans wielded over its investigation. At any rate, the evidence is pretty damning. And yes, shame on Jelena McWilliams, Gruenberg’s Republican predecessor, for doing nothing to address the inspector general’s report. Were she still chairman I’d say Biden should fire her. (She resigned two years before her term ended, reportedly under pressure from Democrats regarding unrelated regulatory matters.)

But Gruenberg is chairman now. I can’t agree with Kuttner that the regulatory stakes are too high to fire him. The stakes are never too high to fire a regulator so apparently isolated and obtuse about the workplace over which he presides. Especially on a Democratic issue like sexual harassment (about which Biden, incidentally, is still haunted by the ghost of Anita Hill). The toxic workplace environment at the FDIC hasn’t received much attention from the general public, but if Biden does nothing it won’t be hard for Republicans to turn this into a campaign issue. Gruenberg’s got to go now.