Why do politicians put up with insults from pensioners?

You’d expect the Prime Minister to be thick-skinned but when he has expended so much literal and political capital on pensioners only to be accused of hating them you wonder how he keeps his cool, says Joseph Dinnage Being a frontline politician, particularly in the age of the keyboard pundit, is not a job for [...]

You’d expect the Prime Minister to be thick-skinned but when he has expended so much literal and political capital on pensioners only to be accused of hating them you wonder how he keeps his cool, says Joseph Dinnage

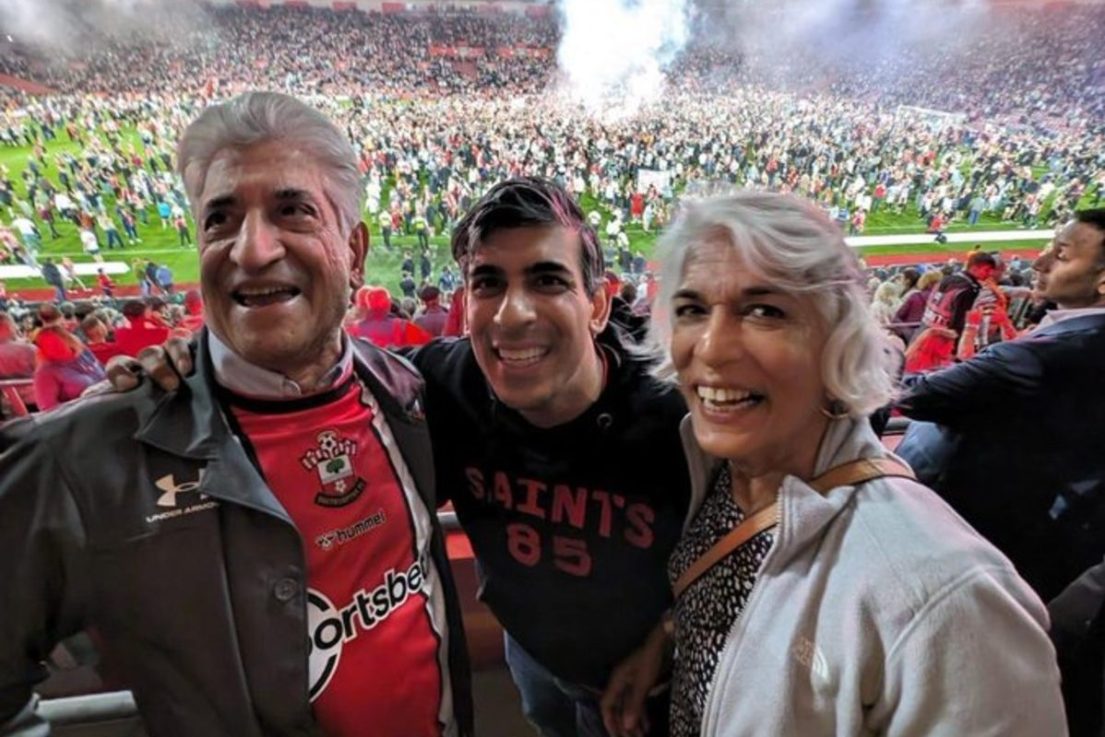

Being a frontline politician, particularly in the age of the keyboard pundit, is not a job for the thin-skinned. A scroll through the Prime Minister’s Twitter page is testament to this. After all, it only took Rishi Sunak posting a picture of him and his folks at a Southampton game to trigger a torrent of abuse.

Perhaps this is just part of public life. But some insults are so absurd that you wonder why our politicos put up with them.

One such example came last week, when Sunak entered the lion’s den that is ITV’s Loose Women. Joining him on the panel was broadcaster Janet Street-Porter, who took him to task on his treatment of her generation when she asked ‘why do you hate pensioners?’

Kudos to Sunak for keeping his cool. It must have taken a lot. Especially when one considers the sheer amount of political and literal capital his party has spent on rewarding the elderly to the detriment of, well, pretty much everyone else.

Since the triple lock on state pensions was introduced (which guarantees that they rise each April by either inflation, average wages or 2.5 per cent) in 2010, the cost of the system has soared to £78bn. Adding insult to injury, the Office for Budget Responsibility predicts that the policy will cost taxpayers an extra £10bn a year by 2034.

Despite these costs and a slew of recommendations to scrap the triple lock, the Tories have retained their commitment to it. Last April, state pensions increased by 8.5 per cent, meaning that those on the new flat rate (those who reached the pension age after April 2016) are now receiving £221.20 a week.

Pensioners remain unmoved by this generosity, demanding instead to know why they ‘lost out’ in March’s Budget. All the while, Britain’s young are getting a comparatively bum deal.

Generation Z and the millennials get a lot of flak, much of which is warranted – we are, by and large, quite irritating. But that cannot justify the intergenerational inequality that now blights our society. The Resolution Foundation has calculated that while someone born in 1956 will pay £940,000 in tax and enjoy benefits to the tune of £1.2m, those born in 1996 will receive less than half that amount.

Fine. We might be drawing less from the state than our grandparents, but at least we’ll end up earning more and owning a home. No such luck. Real wages have stagnated and as my colleagues at the Centre for Policy Studies have endlessly highlighted, the housing market is skewed against the young. While older generations enjoyed the affordability that came with the housebuilding boom of the mid-20th Century, those my age are stuck with extortionate house prices because of our decades long inability to build. Gallingly, this is largely due to older, property-owning Nimbys being able to block developments at every juncture.

So it’s no wonder, given our gerontocratic turn, that Britain is starting to look like Bugsy Malone in reverse. A ballooning tax burden, soaring house prices and low wages have undoubtedly contributed to our declining birth rate. In the last decade, we have seen a 22 per cent fall in births among mothers born in the UK.

It doesn’t have to be this way. These outcomes are the result of political choices made by successive governments which favour an elderly voting base at the expense of the young. If the Tories are due a period in the wilderness, a top priority must be making plans for forging an economy which serves those inheriting it as much as it does for those who created it.

Joseph Dinnage is deputy editor of CapX