Why the Democrats Won’t “Restore Roe” Anytime Soon

Campaigning this spring in Florida, the latest state to enact a six-week ban on abortion, President Biden told the crowd that Americans need only “elect a Democratic Congress, and Kamala and I will make Roe v. Wade the law of the land again.” The line, delivered under a banner that read “Restore Roe,” drew the same applause from the party faithful that it’s gotten ever since Biden started deploying it after the Dobbs decision in 2022 ended nationwide abortion rights. In the nearly two years since, with the erosion of abortion rights propelling Democrats to unexpected victories in one election after another, the “codification” of Roe has only become more central to the party’s electoral message.There’s just one problem: There’s next to no chance the 2024 elections will result in the restoration of Roe.The political incentives for Biden to claim otherwise are clear. Despite a moderate bump in polling this spring, he continues to lag Donald Trump in most swing-state and national surveys. He is particularly weighed down by a lack of enthusiasm in some traditionally reliable Democratic groups, like young voters, among whom abortion rights polls far better. But his campaign promise misrepresents Congress’s political dynamics and constitutional authority, and wholly ignores the Supreme Court’s composition—thereby giving false hope to voters who are motivated to go to the polls to restore the prior status quo on abortion rights.First, the likelihood that Democrats will have the votes to even pass such a bill is slim. The party would have to win majorities in both chambers of Congress, a task that requires not only flipping the House of Representatives but winning a clean sweep of Senate races in five swing states and two red-leaning states this fall. Given Republicans’ near-certain pickup of retiring Sen. Joe Manchin’s West Virginia seat, such an astronomical success—a possibility given polls currently show Democratic Senate candidates outperforming Biden but one that would be in defiance of Americans’ recent shift away from split-ticket voting—would still leave them with a bare majority of just 50 seats. All 50 Democrats would then need to sign on to changing the filibuster in order to allow the bill to pass with a simple majority. The retirements of Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, the Democratic caucus’s lone holdouts on the 2022 effort to weaken the rule, make that change possible—although, as the past has proved, politicians in both parties often vote differently when the stakes are laws, rather than campaign messages.But there are also the problems of the bill itself. The Women’s Health Protection Act, Democrats’ ordained vehicle for codification, guarantees a right to abortion broader than did Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 ruling that actually governed precedent (rather than Roe) until 2022. While Casey protected the right to abortion up until viability—generally deemed to be around 24 weeks gestation—it allowed many restrictions before that point, provided they did not impose an “undue burden” on the woman. As its proponents themselves tout, the WHPA seeks to go back in time to the pre-Casey jurisprudence of the 1970s and 1980s: It would prohibit nearly every pre-viability restriction. That includes parental involvement laws that exist in nearly 40 states, and the bypassing of a federal religious exemption law, which was authored by Senator Chuck Schumer (the current Majority Leader) and passed Congress nearly unanimously in 1993. Anyone is free to prefer that scheme to Casey—polls show that tens of millions of Americans do—but a majority of the Senate so far does not. Multiple Democratic senators—including Tom Carper, Tim Kaine, Bob Casey, and Joe Manchin—have previously backed restrictions that the bill would prohibit, and the only two self-identified pro-choice Senate Republicans already oppose the legislation. With the prospect of an actual law on the line, how far a theoretical bill would go is a both crucial and open question. Sticking to the WHPA’s scope could lose more moderate members, but any erosion could threaten progressive support—all in the context, remember, of razor-thin majorities at best.There is yet more. Even if Democrats achieved unified control of Congress, and even if they mustered a mutually agreeable bill across the finish line, Congress’s ability to bypass the Supreme Court here is extremely murky. Even before considering the court’s 6-3 conservative majority, you need not be a judicial originalist to acknowledge that Congress is limited in its authority to directly circumvent the judiciary. For example, even liberal judicial analysts and congressional Democrats acknowledged that Congress lacked authority to codify Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case that required states to recognize same-sex marriage.So where does the WHPA find the authority for federal legislation? Both the pre- and post-Dobbs iteration cites two portions of the Constitution: the enforcement power of the

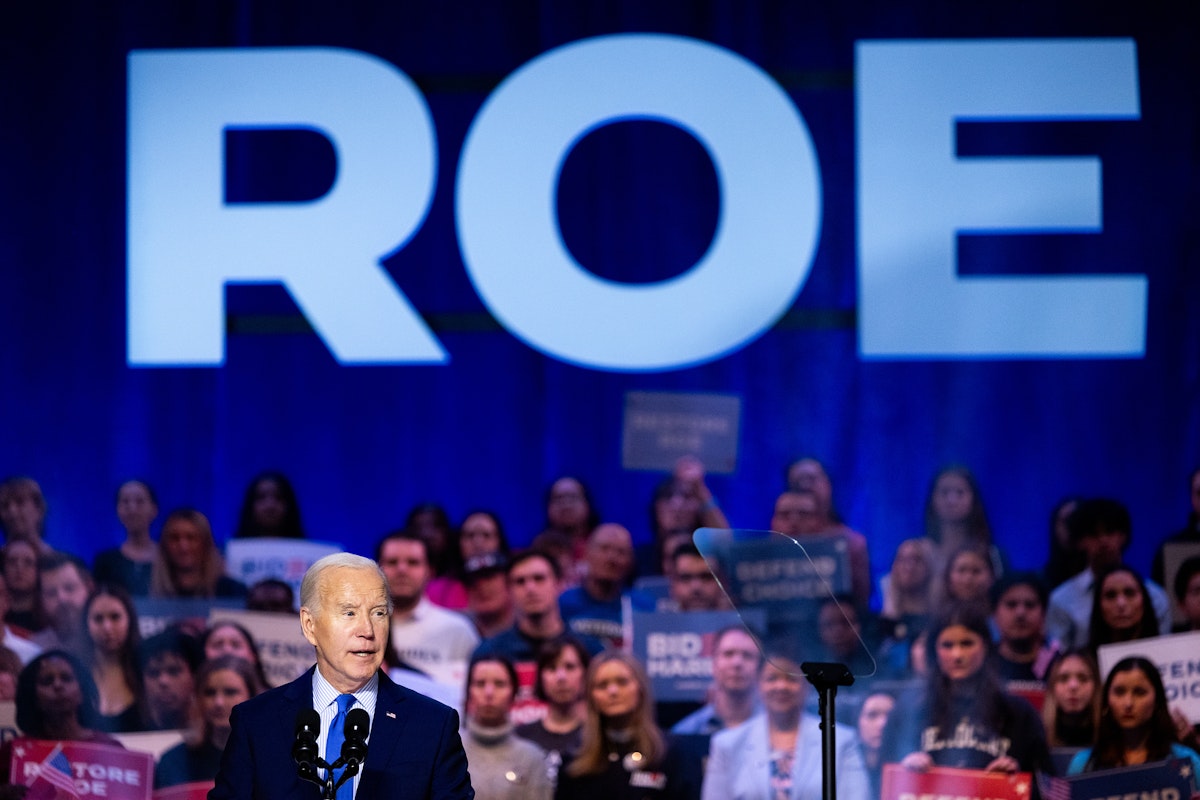

Campaigning this spring in Florida, the latest state to enact a six-week ban on abortion, President Biden told the crowd that Americans need only “elect a Democratic Congress, and Kamala and I will make Roe v. Wade the law of the land again.” The line, delivered under a banner that read “Restore Roe,” drew the same applause from the party faithful that it’s gotten ever since Biden started deploying it after the Dobbs decision in 2022 ended nationwide abortion rights. In the nearly two years since, with the erosion of abortion rights propelling Democrats to unexpected victories in one election after another, the “codification” of Roe has only become more central to the party’s electoral message.

There’s just one problem: There’s next to no chance the 2024 elections will result in the restoration of Roe.

The political incentives for Biden to claim otherwise are clear. Despite a moderate bump in polling this spring, he continues to lag Donald Trump in most swing-state and national surveys. He is particularly weighed down by a lack of enthusiasm in some traditionally reliable Democratic groups, like young voters, among whom abortion rights polls far better. But his campaign promise misrepresents Congress’s political dynamics and constitutional authority, and wholly ignores the Supreme Court’s composition—thereby giving false hope to voters who are motivated to go to the polls to restore the prior status quo on abortion rights.

First, the likelihood that Democrats will have the votes to even pass such a bill is slim. The party would have to win majorities in both chambers of Congress, a task that requires not only flipping the House of Representatives but winning a clean sweep of Senate races in five swing states and two red-leaning states this fall. Given Republicans’ near-certain pickup of retiring Sen. Joe Manchin’s West Virginia seat, such an astronomical success—a possibility given polls currently show Democratic Senate candidates outperforming Biden but one that would be in defiance of Americans’ recent shift away from split-ticket voting—would still leave them with a bare majority of just 50 seats.

All 50 Democrats would then need to sign on to changing the filibuster in order to allow the bill to pass with a simple majority. The retirements of Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, the Democratic caucus’s lone holdouts on the 2022 effort to weaken the rule, make that change possible—although, as the past has proved, politicians in both parties often vote differently when the stakes are laws, rather than campaign messages.

But there are also the problems of the bill itself. The Women’s Health Protection Act, Democrats’ ordained vehicle for codification, guarantees a right to abortion broader than did Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 ruling that actually governed precedent (rather than Roe) until 2022. While Casey protected the right to abortion up until viability—generally deemed to be around 24 weeks gestation—it allowed many restrictions before that point, provided they did not impose an “undue burden” on the woman. As its proponents themselves tout, the WHPA seeks to go back in time to the pre-Casey jurisprudence of the 1970s and 1980s: It would prohibit nearly every pre-viability restriction. That includes parental involvement laws that exist in nearly 40 states, and the bypassing of a federal religious exemption law, which was authored by Senator Chuck Schumer (the current Majority Leader) and passed Congress nearly unanimously in 1993.

Anyone is free to prefer that scheme to Casey—polls show that tens of millions of Americans do—but a majority of the Senate so far does not. Multiple Democratic senators—including Tom Carper, Tim Kaine, Bob Casey, and Joe Manchin—have previously backed restrictions that the bill would prohibit, and the only two self-identified pro-choice Senate Republicans already oppose the legislation. With the prospect of an actual law on the line, how far a theoretical bill would go is a both crucial and open question. Sticking to the WHPA’s scope could lose more moderate members, but any erosion could threaten progressive support—all in the context, remember, of razor-thin majorities at best.

There is yet more. Even if Democrats achieved unified control of Congress, and even if they mustered a mutually agreeable bill across the finish line, Congress’s ability to bypass the Supreme Court here is extremely murky. Even before considering the court’s 6-3 conservative majority, you need not be a judicial originalist to acknowledge that Congress is limited in its authority to directly circumvent the judiciary. For example, even liberal judicial analysts and congressional Democrats acknowledged that Congress lacked authority to codify Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case that required states to recognize same-sex marriage.

So where does the WHPA find the authority for federal legislation? Both the pre- and post-Dobbs iteration cites two portions of the Constitution: the enforcement power of the Fourteenth Amendment, and Article I’s commerce clause granting Congress the power to regulate economic activity.

But the Fourteenth Amendment is wholly moot now that the court has ruled the amendment confers no right to abortion, and Congress’s commerce authority has been notably curtailed since the 1990s, when a far less conservative court—one in which a majority still upheld the right to abortion!—first began to narrow its interpretation. If the current court has already ruled that abortion rights have no basis in the Fourteenth Amendment—the entire crux of the Dobbs decision—and if previous, less conservative iterations circumscribed Congress’s economic regulation authority, why on earth would it uphold this law?

That question only becomes more glaring when considering that the chief organizing principles of the conservative judicial project have been the elimination of the right to abortion and the curtailment of the federal government’s power to enact economic regulation. The notion that this court—the culmination of that decades-long project—would allow the reversal of its decision eliminating the national right to abortion on the basis of an expansive definition of the commerce is almost laughably naive.

Still, now that Trump has reversed (for now) his previous support for federal abortion restrictions, Democrats are increasingly relying on the pitch of Roe codification as the campaign goes on. The fact that they have managed to convince so many voters that it’s a possibility is an unfortunately familiar sleight of hand.

During the successful efforts to pass the 2022 Respect for Marriage Act, countless members of the party framed the bill as “codifying Obergefell” or “codifying marriage equality.” In reality, the bill did neither: It repealed the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, which for federal purposes like tax filing and Social Security benefits defined marriage as being exclusively heterosexual. It was a worthy and significant legislative achievement. But it did not recognize a federal right to same-sex marriage and require all states to recognize that right, as Obergefell did, because Congress does not have authority over states’ marriage laws any more than it has authority over their income tax rates or DMV hours. Unfortunately, that did not stop many many journalists, commentators, and even Republican politicians from parroting the line—aiding Democratic efforts to frame the legislation’s passage as on par with Obergefell itself. The White House eagerly amplified the equivalence.

The 2024 elections will profoundly shape federal policy on reproductive rights in a number of ways—from FDA policy on mifepristone and emergency contraception, to HHS policy on emergency procedures, to the Justice Department’s enforcement of the Comstock Act, to, most crucially, judicial appointments—but a wholesale restoration of the pre-Dobbs landscape is not among them. We already live in a time of deep disillusionment with government and political leaders. Imagine how disheartening it would be for voters if they did return full control of Washington to Democrats next year, only to watch the promised federal abortion right fail to materialize.

The president’s political fortunes may rest on Americans’ buying into his false promise on Roe. But the rest of us don’t have to pretend. The truth is that the legality of abortion in states like Florida will depend on its own citizens, who will vote this November on a proposal to enshrine the right to abortion in their state constitution. Early polls show it may well pass. It just won’t have anything to do with Joe Biden.